Horizon and Resolution

…in Hito Steyerl’s Work

The John Cabot University COM Department’s lecture series Digital Delights and Disturbances presents a conversation with filmmaker, artist, and theorist Hito Steyerl on her practice on Thursday, February 5 at 6:30pm in Aula Magna Regina, Guarini Campus, Via della Lungara 233, Rome.

Her work integrates communications media into cinematic installations that blend documentary techniques, speculative fiction, and first-person narrative as a way of engaging with global, digital, and networked life. Through multimedia storytelling—often infused with a sharp sense of humor—her practice critically reveals the power structures embedded in digital media and, more recently, artificial intelligence.

Hito Steyerl‘s practice examines the proliferation of digital images and their political, social, and technological implications. Working across video, installation, essays, lectures, and photography, her work critically engages with issues of militarization, surveillance, migration, globalization, and artificial intelligence, interrogating the power structures embedded in contemporary media culture. Steyerl has held major solo exhibitions at institutions including the Centre Pompidou (Paris), the Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam), the Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles), the Art Institute of Chicago, Kunstmuseum Basel, Castello di Rivoli, and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Seoul), among others. Her work has also been featured in leading international exhibitions such as documenta 12 and the Venice Biennale. In addition to her artistic practice, Steyerl is an influential writer and theorist. Her books include The Wretched of the Screen (2012), Too Much World (2014), and Medium Hot (Verso, 2025). Her recent work The Island, currently exhibited at Fondazione Prada in Milan, addresses themes of information overload, climate crisis, artificial intelligence, and emerging authoritarian tendencies.

The Digital Delights and Disturbances Lectures series is organized and supported by the Department of Communication and Media Studies.

Register for this event here. Access is free but registration is mandatory.

“This flattening-out of visual content—the concept-in-becoming of the images—positions them within a general informational turn, within economies of knowledge that tear images and their captions out of context into the swirl of permanent capitalist deterritorialization. The history of conceptual art describes this dematerialization of the art object first as a resistant move against the fetish value of visibility. Then, however, the dematerialized art object turns out to be perfectly adapted to the semioticization of capital, and thus to the conceptual turn of capitalism. In a way, the poor image is subject to a similar tension. On the one hand, it operates against the fetish value of high resolution. On the other hand, this is precisely why it also ends up being perfectly integrated into an information capitalism thriving on compressed attention spans, on impression rather than immersion, on intensity rather than contemplation, on previews rather than screenings.”

Two coordinates emerge in Hito Steyerl’s work that reveal themselves as potent, counterintuitive tools for navigating the present conjuncture. They are the horizon and resolution. While both concepts are well-studied and likewise Steyerl’s work is wide-ranging, these brief remarks are guided by the claim that there is something unique in her elaboration of the concepts, both as those elaborations point outward to other treatments of the horizon and resolution as well as within her own body of work, theoretical and artistic. The horizon as diagram of the world, joined with what Steyerl calls “the fetish of resolution,” participates in the various injustices that appear to be spreading uncontrollably now. Paradoxically, relating to both in a different way than we do typically offers possible ways out, even as these paths themselves are fraught with danger and risk.

Horizons of Representability

The horizon, we know from phenomenology, is a mobile limit. We can approach it; we can fly toward it in supersonic jets but we can’t pass it. Every moment that we approach it, it stubbornly remains out there, in front of us. In that journey, however, everything changes. The world and its terrain are not familiar, or if familiar, are nonetheless not the same terrain we left. Nothing remains as it was, but the horizon is there still, taunting us, in its way.

But the thing about jets, Steyerl reminds us, is that they can lose the orientation to the horizon that is familiar to those of us who are earthbound. A jet can go into “free fall,” and the interesting thing about free fall, Steyerl relates, is that the horizon can be lost in that moment. One can lose sense of the difference between self and machine. One can lose all orientation. In that moment, the organization of the world that depends on the horizon is lost.

Thus, while the horizon generally organizes and delimits our experience of the world, in key circumstances we can lose “sight” of it or become so disoriented that it can disappear or become so blurred that orientation is lost. Such is the case in many ways in the present moment. A loss of horizon is in play now and it is at the heart of the growth of contemporary fascism, Steyerl shows us. “Representation, as we know it, is heading for a crash—or rather it is nose-diving in a vertiginous tailspin,” she writes in Let’s Talk About Fascism. In that essay, Steyerl notes a pernicious unwillingness to address the obvious return of fascistic political forces. Their return coincides with a kind of loss of horizon, the “vertiginous tailspin” of representation. It is not one, but two kinds of representation spinning out of control: political and cultural representation.

Steyerl builds on Spivak’s distinction between “portrait” and “proxy,” representation that resembles and representation that extends or holds place. For Steyerl, one issue is that political representation is sliding into portrait rather than proxy. And the portraits aren’t even very high resolution. Fascist representation of the world, while purporting to present a high definition picture, is vague and by design blurry in its portraits of the many communities it seeks to dehumanize, marginalize. Steyerl notes there is “almost an inversely proportional relationship between political and cultural representation,” that is, that “the more people are represented culturally and the more they snap one another on their cellphones and submit to Facebook surveillance schemes, the less they matter politically.” Thus, one problem is the erratic and uneven way that both forms of representation slide into “portraits” rather than proxy, portraits that are “not necessarily very good portraits either.” Steyerl admonishes us, however, that all of this does not necessarily lead to fascism. We can be clear about what is happening, get our bearings, so to speak, and orient ourselves differently, realign the horizon, so to speak, and pull out of the tailspin into fascism.

The horizon, however, is ambiguous. Or, better yet, its utility for organizing and orienting us in the world is posterior to and subordinate to another function. The horizon, thus, is not just a visual and mobile limit, it is the diagram of the world that organizes it. Steyerl goes further, and relates the horizon to the structuring, quantifying logics of modernity that would include the “grids” Bernhard Sieghert analyzes. The horizon, as the key line in linear perspective, participates in a specific diagram of the world whose aim is total control. The diagram, Deleuze reminds us, is not simply a drawing or useful visual representation. The diagram “is the presentation of the relations between forces unique to a particular formation; it is the distribution of the power to affect and the power to be affected; it is the mixing of non-formalized pure functions and unformed pure matter,” and thus it is “a machine that is almost blind and mute, even though it makes others see and speak,” As diagrams of and in our world, the horizon and resolution organize specific capacities to see, say, and even imagine the world. “[The] space defined by linear perspective is calculable, navigable, and predictable. It allows the prediction of future risk, which can be anticipated, and, therefore, managed.” A world with a horizon is a world in its place.

To Steyerl, this totalization is not only spatial, as is evident from the question of prediction above. Such linearity, she tells us, establishes not only its peculiar and calculable space, but a peculiar and calculable time: the temporality of linear time. What is born here is the “temporal meaning of perspective: a view onto a calculable future.” Here she echoes, but goes further than Vilém Flusser, who draws a distinction between linear time, that is history, inaugurated by the invention of alphabetic writing to code the world, and surface time, through images as a means of coding the world; that is, myth. Steyerl goes further than Flusser here because she shows us the futurity of that so-called history. Not an arrow we find already shot and in motion like time’s arrow itself, but one that is aimed—a weapon.

We cannot, then, simply appeal to the horizon, and the perspective that uses it to organize our world, in the fight against fascism, since the horizon, in this view, is part of the reactionary diagram demanding the world be predictable at all costs. Fascism thrives with the loss of horizon, but the horizon, in its way, is fascistic. However, we should be cautious to not give in to the temptation to demand to see the world perfectly clearly, in high resolution, that is. We must be careful here too, because resolution also presents us with an ambiguous problem.

It Is Important to be Resolute!

As Steyerl admonishes us, there is something neoliberal about the fetish for high resolution images. Like the reactionary diagram of the world anchored by the horizon, our demand for ever higher resolution images of the world conceals, in all their vibrant sharpness, a narrowing and limiting world under control. High resolution images are anchored in “systems of national culture, capitalist studio production, the cult of the mostly male genius, and the original version, and thus are often conservative in their very structure.”

The degraded, imperfect, difficult to decipher poor images she invites us to acknowledge and celebrate offer us a possible interruption to that fetish, even while she is careful to caution us against pretending there are any easy escapes. Absorption and cooptation into the capitalist circulation of value remains a risk even for the lowly poor image.

Whatever risks the poor image faces, its advantages are evident. Poor images, Steyerl shows us, are popular images in a genuine sense. They are the images that “can be made and seen by the many,” and which express “all the contradictions of the contemporary crowd,” thus giving us a “snapshot of the affective condition of the crowd” instead of the high resolution, capitalistic fantasy imposed upon us.

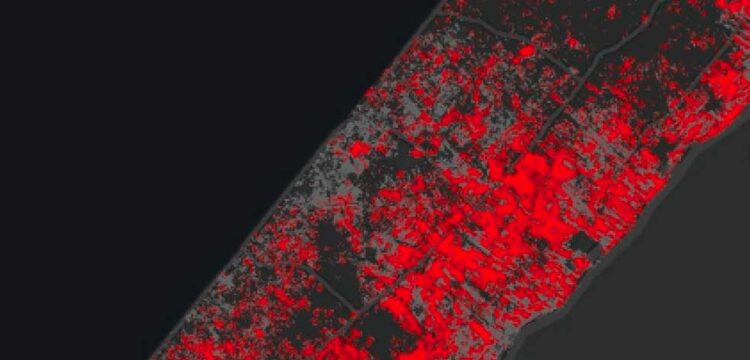

At the same time, it is worth pointing out, not all low resolution images are equal. Some kinds of poor images are thus to conceal the State’s crimes in the world. Eyal Weizman reminds us that the commercially available satellite image of the world is set to half meter of resolution per pixel. That resolution is not accidental: it is meant to blur human bodies. But it also blurs state crimes, as Weizman’s studio Forensic Architecture reveals in their patient analyses .

Thus, there is a double tension at the heart of the problem of resolution, like there was with the horizon. If we can’t look to the world with the expectation of being oriented, without those orienting structures controlling us, we also cannot celebrate their loss simply, embracing the “free fall,” for if we are not diligent and cautious, it is in that free fall where fascism offers its own horizon. Likewise, we must be attentive to the clarity of the images of the world on offer. Undermining the fetish of high resolution entails its own risks, which must be confronted and undertaken, not ignored or avoided.

Design Horizons

In the essay How to Kill People, A Problem of Design Steyerl analyzes a 3D rendering of a future rebuilding of Diyarbakir, Turkey, the unofficial capital of the Kurdish region. The problem there, as now in the various fantasies of a Western-controlled Gaza riviera, is a junction of the horizon and the fetish of high resolution. In her criticism of the Turkey diagram of the new city rebuilt after the expulsion of the Kurdish population, she argues what is at play is a kind of Design-zum-Tode, playing on Heidegger’s Sein-zum-Tode. Design-toward-death as a grim extension and perversion of our condition of being-toward-death. It’s worth recalling here too the role of projection and project in Heidegger that connects to being-toward-death. In a certain sense, since we are tasked with projecting a life as a project, design is already there, in Heidegger. But the kind of design Steyerl sees in Turkey, and the kind of death it structures is a much more political matter, an area of human activity on which Heidegger’s thinking was much weaker. The way out, then, according to Steyerl, is to find an “opposite design, a type of creation that assists pluriform, horizontal forms of life.”

Here I think a new diagram is finally revealed; the horizon returns, it is less disoriented, and though we are in no position to predict the future, we are beginning to see more clearly, in greater resolution, the contours of how to project it. A form of designing together, the opposite of Design-zum-Tode, what I call elsewhere Mit-Design, in which resolution is not fetishized, but neither is the poor image substituted for the clear revelation of the world’s injustices, now constantly hidden from our view, or concealed. A horizon appears, too, but one that proposes rather than imposes our orientation toward the future. Steyerl’s creative work, of course, frequently explores that possibility. Her writings and artworks model or prototype the different diagram needed for different future worlds, especially if we remember that the diagram need not resemble what it maps.