Gottfried Semper and Anarchitecture

By its very nature, architecture is an affirmative profession

The exhibition Architecture of the Barricade is opening on May 7th at Arsenale Institute, in Venice. Curated by Bastiaan D. van der Velden and Wolfgang Scheppe, based on a concept developed in collaboration with Sara Codutti, the research exhibition explores the iconography of the barricade as an architectural entity. The exhibition includes a central work by Lawrence Weiner from 1989, which is directly related to our topic.

As much as the practitioners of this business may consider themselves artistically autonomous, socially engaged and politically committed, their work is in principle–and with increasing inevitability–constrained by the prevailing standards and economic calculations that shape the commercially driven choices of their clients, namely real estate developers. Anything that fails to meet their criteria of profitability is unlikely to be realised as a building.

The fact that the exemplary figure in the city’s spatial policy, the prefect Baron Haussmann (1809-1891), was not an architect but a lawyer is therefore as unsurprising as the fact that he instrumentalised architecture for an urbanistic maxim of the forced pacification of the city under the authority of Napoleon III and the business world it favoured. It was architecture that created order in the metropolises of the early industrial age through the physical transformation of the street against the traditional methods of insurrection and, in particular, the building of barricades by the dangerous classes Walter Benjamin dealt with the way in which Haussmannisation relates to the barricade tradition in a separate chapter of his Arcades Project: “The true purpose of Haussmann’s work was to secure the city against civil war. He wanted to make the erection of barricades in Paris impossible for all time.” [1] In his aesthetics of perspective visual axes—“L’embellissement stratégique”—Benjamin only recognised the strategic purpose of depriving the revolt of the physical conditions provided by urban space.

In contrast to the rationality of the prosperous real estate speculation of the Napoleonic era, the barricade formed a threatening negative volume that, paradoxically, itself also bears the determinations of architecture. The artists who gathered around Gordon Matta Clark in the 1970s under the banner Anarchitecture adopted Richard Nonas’s term “hard-shell” [2] to denote the ossification of the prevailing societal conditions engineered by property developers and the architectural profession in particular. The latter seemed to them insurmountably linked to the principle of property in its most radical form of exclusion from space. With their name Anarchitecture however, they implied the possibility of a subversive definition of architecture. This applies to the creation of negative spaces, which paradigmatically include the barricade.

Long before this, the decisive author in architectural history who believed he could learn from the conceptual form of the barricade and, conversely, use his expertise as a master builder to help it achieve greater practicality in the street fighting of the rebellious population, was the most important German architect and architectural theorist of the 19th century alongside Schinkel, Gottfried Semper (1803-1879). When, with the explicit self-assurance of an architect, he became active in the field of a system-transcending architecture of subversion in order to take sides in the revolt in Saxony in May 1849 in favour of the rebellion and against feudalism, he took great personal risks. After all, the rebellion in which the court architect and professor of architecture at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts took part was directed against his immediate employer and patron, the King of Saxony. The consequences of the suppression of the disobedience proved to be severe for the further course of Semper’s biography.

As an architecture student, Semper had already witnessed the July Revolution in 1830, whose proverbial three glorious days on the barricades he enthusiastically experienced in Paris. These Les Trois Glorieuses resulted in the expulsion of the reactionary monarch Charles X and the installation of the “Citizen King” Louis-Philippe. When his reign in turn was brought to an end 18 years later by the bourgeois February Revolution of 1848 and the subsequent bloody suppression of the social revolutionary June Uprising heralded the dawn of the golden age of the bourgeoisie in France, the impetus of republican aspirations for freedom in its various nationalist guises swept across Europe until July 1849. The climate of resistance to the Restoration, known as the “Vormärz,” finally reached Saxony in the states of the German Confederation and manifested itself in the Dresden May Uprising of 1849.

There, Semper teamed up with his friend, the court conductor Richard Wagner (1813-1883) and the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin (1814-1876) to participate with great determination in the front line of an uprising against the absolutist rule of King Frederick Augustus II.

While Wagner acted as an observation post for the attempted coup, Semper was given the task of preparing the barricade battle as commander and above all as an engineer—undoubtedly one of the central tasks. Bakunin, who arrived on 3 May, established himself as the de facto military leader of the provisional government. The heterogeneous juxtaposition of the order of battle, in which a professional proletarian revolutionary joined forces with the representatives of the republican-minded bourgeoisie, whom he mildly ridiculed, was the special point of this historical constellation.

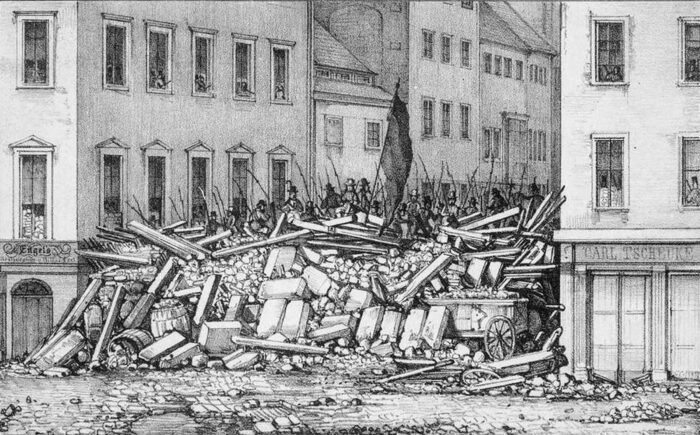

Shortly after his arrival in Dresden, Bakunin began publishing inflammatory articles in the Dresdner Zeitung. In one of them, he coined the programmatic term “barricade weather.” It describes the historical moment of a turning point: when a revolutionary subject appears in the collective action, which materialises its resistance in the sudden and spontaneous momentary creation of an obstruction built from found objects. This blockage abruptly stands in the way of the state forces of the existing order and at the same time documents the emergence of a collective will of the subordinate subjects. As a former artillery officer, Bakunin was aware that the heroic phase of barricade building, which Semper was still trying to perfect in the craftsman’s ethos of the master builder, was already beginning to become anachronistic. The increasing mobility of artillery gradually thwarted its historical efficiency.

But conversely he also recognised the metaphorical power of barricade building at the very moment of its obsolescence, because it remained the dramatic sign of a mass uprising and that dangerous consensus in the rejection of allegiance that continued to instill terror in the rulers. Even the army commander of the Prussian contingent spoke of the “terrifying image” that the slogan “To the barricades!” evoked. In the typical tone of his irony, Bakunin therefore suggested to his moderate comrades-in-arms—at least according to legend—that the portraits of the famous Sistine Madonna by Raphael and the Virgin and Child by Murillo from the Royal Painting Gallery, the creation of his fellow combatant later known as the Semper Gallery, should be hoisted onto the ramparts of the barricades, as the classically educated Prussians would hardly be able to vandalise the most sublime art treasures of Western culture in the course of their advance.

As members of the Dresden Communal Guard, the dissimilar companions became key players in the revolutionary events, in the course of which Semper, dissatisfied with the improvised roadblocks, advocated tectonic improvements that would turn them into strategically thought-out fortifications of the resistance. Above all, they were intended to stand in the way of the support of the Prussian army called upon by the Saxon monarch. Mainly with the monumental construction of a blockade in Wilsdruffer Gasse, which he designed, he endeavoured to create an exemplary prototype for the insurgents’ defence against the superior military formations of the authorities. It was to be the model for all of the other 108 barricades that were to be erected in Dresden’s Old Town.

Contemporary chroniclers, even among the political opponents, were full of praise for Semper’s barricades, which were designed “with great strategic prudence and correctness.” “They were so firmly constructed from the granite slabs of the pavements and the large square cobblestones that those of them that were later hit by artillery proved impenetrable even to several hours of full-bullet and shell fire.” [3] In fact, the psychological effect they had was obvious at first: The beacon of their erection apparently sent the king, part of the court and his ministers fleeing in haste on 4 May. A steamship manned by large military forces brought the royal couple and their cabinet to Königstein Fortress. However, in the course of the battle that began the following day, it quickly became apparent that the proud barriers could not withstand the fire from the modern ordnance with its new tactics of flanking maneuver by means of pincer movements for long.

The three friends managed to escape, while several hundred mainly young people fell victim to the fighting and the subsequent atrocities committed by the armed forces. Semper and Wagner, on the contrary, managed to escape via Paris, initially to the safety of Switzerland as a temporary exile. Bakunin’s fate was less fortunate. He was arrested in Chemnitz and was first imprisoned in an Austrian fortress before being extradited to the Russian Tsar in 1851. It was not until a decade later that he was able to escape from imprisonment and exile. After the suppression of the insurrection, Semper was labelled a “Democrat I. Class,” declared the main instigator and persecuted internationally by the reactionary royal authorities. He was never to return to Dresden. Even though his arrest warrant was cancelled in 1863 and he was commissioned to rebuild what was later known as the Semperoper, the construction management of which he entrusted to his son, he never saw the famous structure nor the Semper Gallery, which was also built according to his plans—the most iconic buildings for which he is known today.

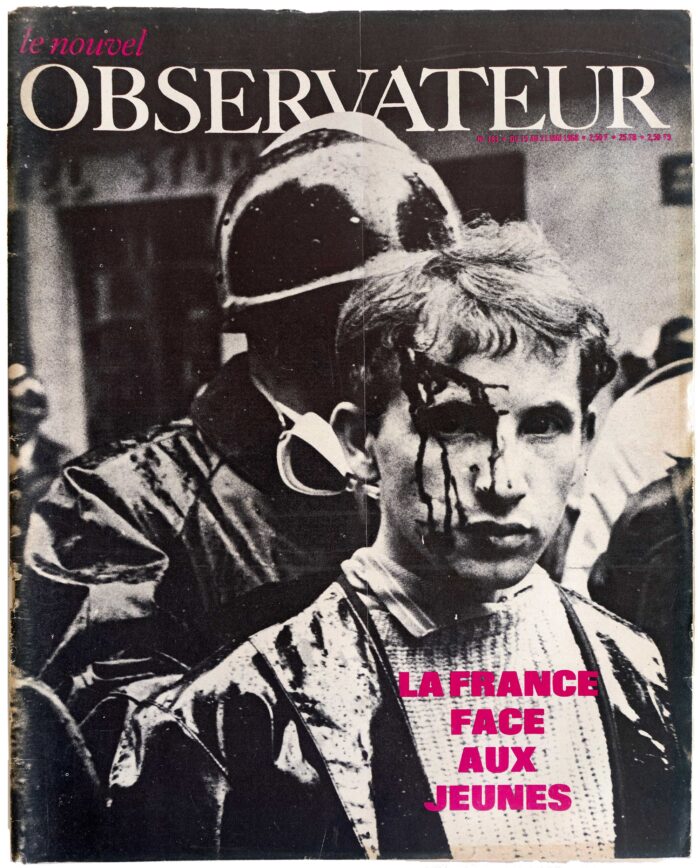

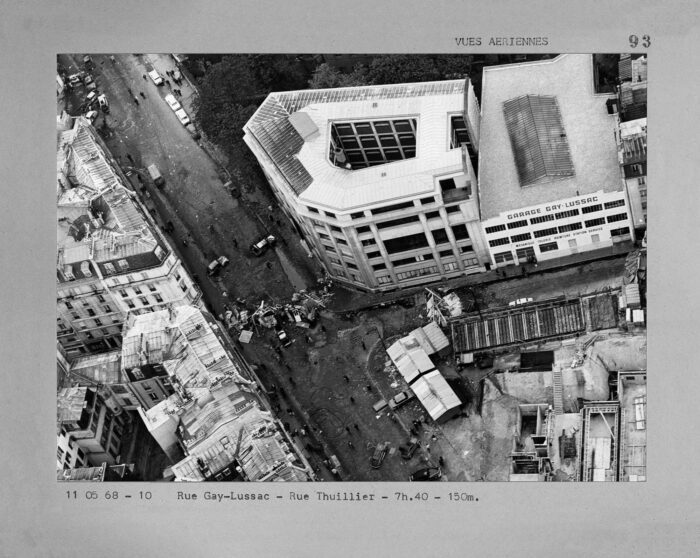

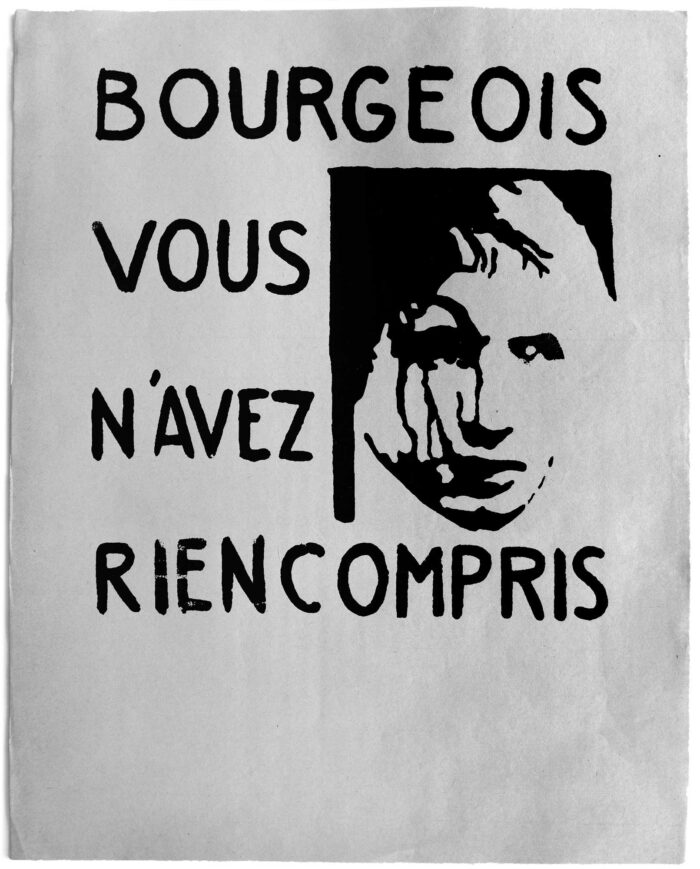

The present project takes this moment of fierce civil courage and dissidence in the life of the celebrated mastermind among the master builders of his time as the starting point for using the Arsenale Institute’s extensive research collection to examine the iconography of the barricade from the perspective of its essentially architectural substance as a spatial and symbolic form—a perspective from which it has hardly been studied to date. The selected documents span 400 years, from the earliest barricades of the late Renaissance in the 16th century to those of the student revolt in Paris in May 1968.

In our present moment—when property development once again advances a vision of the city as an exclusive enclave of luxury, excluding anyone who cannot afford it and so echoing second Empire Paris and Haussmann’s remorseless redesign—architecture might profit from a measure of selfrelativisation, even humility. The barricade’s heap of rubble serves as a potent reminder: every built form, however refined, begins as a pile of stone and timber and is destined, in time, to return to that state. Within this metaphor lies the teleology of the discipline itself: architectural ambition is born of an accumulation of raw matter and, once its cycle is complete, will inevitably fall back to such and subside into ruin.

[1] Walter Benjamin: Das Passagen-Werk, VI. Haussmann oder die Barrikaden, in: Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften V. I, Hrsg. Rolf Tiedemann, Frankfurt a. Main 1991, p. 57.

[2] Richard Nonas was a member of the Anarchitecture group inspired by Gordon Matta Clark. He first mentioned the much-cited term “hard-shell” in a letter to Richard Armstrong dated 14 October 1980.

[3] Hans Blum: Die deutsche Revolution 1848–1849, Florenz und Leipzig 1898, p. 404.

The description of Semper’s performance by his direct opponent Count Waldersee, who served as commander of the Prussian auxiliary troops during the May Uprising in Dresden in 1849, is particularly revealing. In his book on the techniques of urban warfare, he writes about Semper’s barricades: “They were built with the utmost care under the guidance of the court architect Semper, who rewarded many royal favours with highly treacherous ingratitude. (…) They were formally little fortifications, reaching up to the first floor of the houses, skilfully assembled from the ashlars of the pavement, resistant even to heavy artillery thanks to the sloping pavement slabs, and equipped with breastworks.” Graf Friedrich von Waldersee: Der Kampf in Dresden im Mai 1849, Berlin, 1849.