From Commons to NFTs

Digital objects and radical imagination

The following text is a foretaste of the publication From Commons to NFTs edited by Felix Stalder and Janez Fakin Janša that Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana is about to publish as part of a conference of the same name to be held in Ljubljana on 12 November. The event will bring together artists, hackers and researchers to critically examine the shift in digital culture from open sharing to crypto-based forms of ownership.

A first version of this text was published on 31 January 2022 in the online magazine Makery.

Digital culture has always been a source of radical social imagination. In a capitalist society, there is little that is more radical than redefining property relations. Over the last 50+ years, there have been three ways to think of digital objects—blobs of data, software code, informational “content”—as property: intellectual property (copyright and patents), communal property (under free licenses), or “authenticated copies” (blockchain-based non-fungible tokens, NFTs). Property relations shape all aspects of society and culture, and each of these imagined forms advances a distinct social vision. The vision expressed through intellectual property is structurally conservative, foregrounding firms that produce commodities and artists marketed as individual geniuses. The push for communal property and for “authenticated copies”, however, contains quite radical—and quite radically different—breaks with the status quo. It is possible that yet another way of organising the digital as property might emerge in the future (who knows?). However, at this historical moment, it’s the vision of communal property and the vision of authenticated copies that formulate radical departures from the status quo, though not necessarily for the better.

Commons: Digital objects as a medium of community

In the early 1980s, the software-as-copyright model was consolidated by companies such as Microsoft, whose CEO, Bill Gates, introduced this framing in his (in)famous Open Letter to Hobbyists by suddenly calling the previously accepted sharing of software “stealing”. His vision was that computer users should be divided into “producers” (of source code) and “consumers” (of binary code) and that their relationship should be managed as a commercial transaction.

The enforcement of this vision triggered a countermovement that viewed software primarily through the lens of the previous open peer culture and thought of ways to restore and expand the community of users/programmers. Introducing the copyleft license, an ingenious legal hack to turn social dynamics of copyright upside down (copyleft), this movement was able to legally safeguard individual autonomy (ability to use and adapt your software, thus breaking out of the mold of the passive consumer/end-user) and the ability to build community (the right to share copies and improvements, thus rejecting the exclusivity of commercial transactions). The main objective of this Free Software movement was political/ethical, to set everyone “free to help their neighbours”, as activist Richard Stallman put it. During the 1990s, this movement grew rapidly, not least because the Internet drastically reduced the costs of distributing digital objects and coordinating a large number of volunteers. Thus, the community that was initially only imagined came into being spectacularly.

While the communitarian ethos and values remained strong, the driving force soon became more practical. The underlying conceptualisation of software as a shared resource, the ability of a distributed community to draw on this resource, independently of contracts and product release schedules, turned out to be a very productive framework to develop complex knowledge goods. At the turn of the century, these two forces—the counter-cultural communitarian roots of net culture and the rising financial and cultural power of internet-centric organisations—created a heady mix of practical and utopian reflection on the power of the Internet to overcome old limitations and create a realm of freedom and cooperation. [1]

As access to, and familiarity with, the Internet expanded beyond highly technical subcultures, the question of digital property became virulent in terms of non-technical “content” as well. By connecting the new experience with free software to the old practice of the commons, a new horizon of social possibility emerged, [2] partially overlapping the vision of the global justice movement that “another world is possible”.

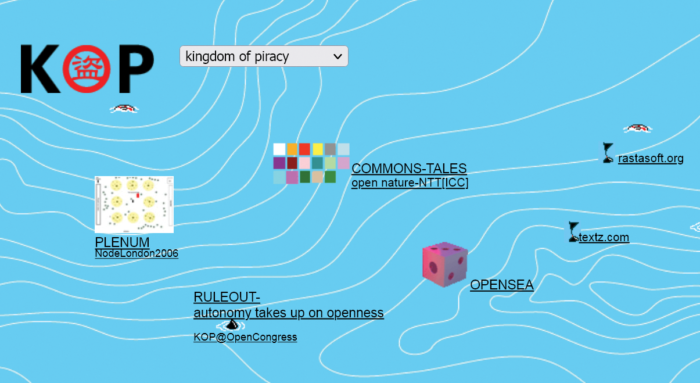

Sharing was again redefined, this time as “caring”, and even openly illegal practices, such as large-scale piracy, were integrated into this new horizon as “file-sharing”, framed as a form of civil disobedience to hasten the inevitable emergence of a post-copyright culture. Kingdom of Piracy (2002–2006), one of the first international art projects that addressed this new culture, declared “the free sharing of digital content—often condemned as piracy—as the net’s ultimate art form.”

On the legal side, projects such as Creative Commons ported the basic insights of the free software licenses to the cultural realm. In field after field—scientific and cultural publishing (open access), collaborative writing (e.g. Wikipedia), music (netlabels), data management (open data) and many more—new “open” approaches were innovated that treated digital objects as a non-rival, shared resource from which people could take with minimal restriction and to which they should contribute according to their ability. It was a participatory, democratic vision.

Political economy saw the emerging dynamics as “a-capitalist”, in the sense of not being directly opposed to capitalism, but also not fully contained within its logic. As it turned out, this was both a strength and a weakness of this vision. A strength, because it could harness the capacities of an extremely diverse coalition of actors and establish real innovation and a new collaborative paradigm that is here to stay. [3] (What is more, in the cultural field, it remains a horizon that continues to inspire a search for forms of expression and of being that are not fully subsumed under the totalising logic of commodification.) A weakness, because it left the movement ill-equipped to deal with the constant processes of enclosure (resulting in effective dispossession of the original producers), and its own subsumption into a capitalist logic of “precompetitive collaboration”. Also, new business models were introduced that both undermined the licenses by redefining software as a service (consequently, the requirement to share improvements when distributing adapted free software was removed) and dispensed with copyright by focusing on monetizing the social interaction created by “sharing”. As a result, the digital commons (and its definition of digital objects) remain an important source of techno-scientific innovation, but its utopian social horizon has shrunk, effectively, to a niche.

NFTs: Property from artificial scarcity

On top of a rapidly evolving environment of blockchain-based crypto-currencies, which as technology is largely open-source, a new framework for digital objects has emerged over the last five to ten years, that is inspired from the world of collecting art or other rare items. The two worlds—digital currencies and collector’s items—have come together in the form of non-fungible tokens (NFTs), meaning an entry into a blockchain that represents ownership of something unique, usually residing elsewhere.

The key properties of such (physical or digital) objects are that they are scarce, they bring social status to the owner and they can be traded in specialised markets. As such, this understanding of a digital object is fundamentally opposed to the notion of shared, non-rivalrous resources; indeed, unique or rare items represent precisely the extreme form of rivalry that they themselves need to acquire value. It also dispenses with the need for control over the copy, since it focuses on “originals” that are taken to be fundamentally different from “copies”. In a digital context, the differentiation between “original” and “copy” is from a materialist point of view nonsensical, as there is no original, and all copies are identical. However, the same situation exists elsewhere, for example in photography, where in principle, the first print is equal to the 1000th print of the same image (be it derived from a physical negative or a digital file). Nevertheless, the art market found ways to introduce fine-grained differentiation, from “originals” (i.e. a limited number of prints signed by the artists) to “authenticated reproductions” (made by an exclusive dealer with access to the artist or their estate), books segmented by quality and price, cheap reproductions as posters, postcards, T-shirts, all the way to “poor images” floating around online. Conceptual art, through various forms of “appropriation”, has even found ways to turn mass-produced copies (for example, advertisements) back into new ultra-rarefied originals that sell for multi-million prices. In all of these cases, the value stems less from the material than from the relational properties of the objects. In the case of photography, the closer the copy has once been to the actual artist, the more valuable it is, with the one directly touched, or blessed in some other form, being the most valuable.

In the case of NFTs, scarcity is created by designating, rather arbitrarily, one copy (or a small number of them) stored somewhere as the “original” or “authenticated” one, and then marking this copy by storing a reference to it in a blockchain. The blockchain does not store the rare item, but a token for it. As all transactions are recorded immutably, the current owner of the token can always be determined without a doubt. Perfect for trading. Since the value lies in the ownership of the one authenticated copy, there is no need to control the flow of unauthenticated copies, even if they are materially identical, since it is the relational properties that matter and they are different in each copy.

Again, this new conceptualisation of the digital object as a unique entity has created both practical innovation and a very sizable market, but also a large overshoot of utopian thinking, ranging from the democratisation of ownership and the decentralisation of market art to new genres of cultural expression and entirely new sectors of the “creator economy” in fully digital environments, such as multiplayer online games or Facebook’s Metaverse. For others, it’s a more pragmatic opportunity to finally find a market for their artworks and earn some money, as long as the market allows them to. Given the boom characteristics of the current phase, there is some room for experimentation and unconventional successes, though the inherent logic of the art market tends towards an extremely steep pyramid.

Even though there is a lot of superficial talk about community and democracy (often falsely equated with decentralisation), the social vision advanced through this type of digital objects is highly reactionary. It draws on the deep, right-wing libertarian currents within digital culture, [4] producing a trivial version of Adam Smith’s society of independent shopkeepers as “creators” and fully aligning itself with the mega-trend of financialisation. [5] It does not challenge the already dominant logic of financial speculation and competitive markets, but rather hardens it by enticing ever more people to play by its rules, in another ratcheted up vision of the “ownership society” that is so central to neo-liberalism.

Understood narrowly, this type of digital object reintroduces very old-fashioned social subjects—such as the “genius artist” and the “collector”, a form of a hyper-possessive individual—who are bound together by the exchange of charisma and money. Slightly more broadly, it envisions a world where ownership is the dominant relation of people to each other and to the rest of the world, where—as one art collector puts it in Nathaniel Kahn’s documentary film The Price of Everything (2018)—“money creates involvement” and every possible type of relationship is realised as a commercial transaction. Even more broadly, it envisions a world where competition over and exploitation of scarce resources are the driving forces of social life. The grotesque environmental and social costs are simply abstracted away, in yet another way that this approach hardens and expands the already dominant, highly destructive logic of extractive capitalism.

From a systemic point of view, NFTs are a speculative bubble on top of the much larger speculative bubble of cryptocurrencies. Both represent assets that have no intrinsic or use value, but only pure exchange value, whose valuation rises only as more money flows into the system (a defining characteristic of a Ponzi scheme). Perfect for speculation and, given the unregulated character of this speculation, perfect for rampant fraud, both in the larger world of cryptocurrencies and in the smaller world of NFTs. This makes it hard to believe that both the small and the large bubbles will not burst at some point. Given the size of these bubbles and the desperate state of society even before the crash, the outcome looks pretty grim.

Even if these bubbles burst, these tools and ideas will not disappear. There may be niches in which the concept of an “authenticated copy” on a blockchain will turn out to be useful, and there is no imperative for this need to be tied to cryptocurrencies. But this will presumably be a niche, and not a particularly interesting one at that, most likely featured in multi-player games and the metaverse. However, given the highly centralised nature of these platforms, there is really no need for either blockchains or cryptocurrencies in trading exclusive digital property. We are more likely to pay in dollars and euros to have our exclusive claims registered in an old-fashioned centralised database. Even now, NFT markets already show a surprising degree of technical centralisation.

What’s next?

In their utopian horizon, the commons and NFTs represent radical and radically different visions, and their proponents are taking concrete steps towards realising them, with consequences far beyond the digital. The commons are a constitutive part of a world where people are bound together by a common interest in the non-exploitative use and therefore long-term existence of a shared resource. This points at least partially beyond capitalism and the destructive effects of extractivism, towards a world in which both informational and physical entities can be understood as “matters of concern”. NFTs belong to a world in which all relationships are expressed as commercial transactions, and private property is the main form of existence. Fully subsumed under the imperative of financial capitalism, they will produce the same result, both within the art sphere (extreme inequality) and in relation to the broader non-human world (depletion and degradation).

As always, the question is not a simple either/or, but whether the technological potential of blockchains can be used to advance the social vision of the more-than-human commons. That will not be easy, given blockchain’s deep roots in the most destructive strands of digital culture. But as technologies never disappear, and their possibilities have yet to be fully explored, there is currently no alternative.

[1] Turner, F. (2006). From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. University Of Chicago Press.

[2] Boyle, J. (1997). A Politics of Intellectual Property: Environmentalism for the Net? Duke Law Journal, 47(1), 87–116.

[3] Weber, S. (2004). The Success of Open Source. Harvard UP.

[4] Golumbia, D. (2016). The politics of Bitcoin: Software as right-wing extremism. University of Minnesota Press.

[5] Haiven, M. (2014). Cultures of financialization: Fictitious capital in popular culture and everyday life. Palgrave Macmillan.