Algoregimes

Felix Stalder in conversation with !Mediengruppe Bitnik

The following conversation is part of the book Hyperemployment– Post-work, Online Labour and Automation curated by Domenico Quaranta and Janez Janša, and co-published by NERO and Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana. Featuring words by !Mediengruppe Bitnik (Carmen Weisskopf and Domagoj Smoljo) and Felix Stalder—republished here, and Silvio Lorusso, Luciana Parisi, Domenico Quaranta along with works by !Mediengruppe Bitnik, Danilo Correale, Elisa Giardina Papa, Sanela Jahić, Silvio Lorusso, Jonas Lund, Michael Mandiberg, Eva and Franco Mattes, Anna Ridler, Sebastian Schmieg, Sašo Sedlaček, and Guido Segni, Hyperemployment is an attempt to scrutinise and explore some of these issues. A catchphrase borrowed from media theorist Ian Bogost, describing “the Exhausting Work of the Technology User,” hyperemployment allows us to grasp a situation which the current pandemic has turned endemic, to analyse the present and discuss possible futures.

24/7. Algorithmic sovereignty. Anxiety. Artificial intelligence. Automation. Crowdfunding. Data extraction. Entreprecariat. Exploitation. Free labour. Free time. Gig working. Human-in-the-loop. Logistics. Machine vision. Man-machine complexity. Micro-labour. No future. Outsourcing. Peripheral work. Platform economy. Post-capitalism. Post-work. Procrastination. Quantification. Self-improvement. Social media fatigue. Time management. Unemployment. These are arguably just a few of the many keywords required to navigate our fragile, troubled, scattered present, in which the borders between life and work, home and office, sleep and wake, private and public, human and machine have faded, and in which the personal is not just political but economic.

Where institutional processes disappear into black boxes

Carmen: My app says that we can record for more than 10 hours.

Felix: OK, so it seems to be recording well.

Doma: So we now have two recordings.

Felix: Your interface is much nicer than Doma’s.

Doma: Yeah, mine is the open-source software. (laughs)

Felix: Carmen’s app tells me something is happening. … OK, so let’s start. In 2015, Frank Pasquale, an American legal scholar, published a book called Black Box Society by which he meant that ever more processes in society disappear into black boxes. These are increasingly difficult to audit from the outside—be that from the public or from specialized regulatory bodies. What I really liked about this notion of the black box was that the means by which the blackness is produced is not necessarily only technical. Of course, there are a lot of technical black boxes, automated systems, self-learning systems that are increasingly opaque, but layered on top of that, or sometimes even without the technical layers, there are institutional layers, that make it harder and harder to see inside of institutions. There are all kinds of mechanisms by which the knowledge of interest to an institution never comes out. There are also legal layers; before you even enter an institution, then you have to sign an NDA agreement and all of that, so there are lots of different layers that produce this blackness. In your work, it seems that you also deal a lot with black boxes. What is interesting for you or why are these black boxes worthy of your attention? Why do you try to explore them?

Carmen: I think, for us, often it’s a question of participation. It’s very hard to participate in processes if you can’t get beyond these layers of black boxing. Much of our work is interventionist and tries to involve either ourselves or other people with a system. We find involvement is the only way of opening black boxes or probing them to find out how they work. Something that worries us is that there’s less and less of this involvement on a technological level. It’s very hard to get beyond the screen or the user interface. But you need to go beyond the interface to understand exactly what the decisions you make as a user produce as a reality or as an environment.

Doma: Probing the black box starts with simple questions like, how does Google see the world and what kind of world does it produce for us? We are constantly immersed in these worlds, and they define how we surf, what we see, what’s available for us, what’s visible and explorable for us as a user or as a web surfer. In our works, we just use trial and error most of the time. We shoot at the black box, trying to understand it by what we get back, whether there is something meaningful in it. Like you said, it’s not only the technical part of it, but it’s also the social part or the legal parts. You see that even in buildings. Like, when Google came to Zurich some years ago, and there was no interface for the public in the architecture they built for themselves. There’s no lobby, there’s no local phone number. You cannot call anybody; it’s as if they are there, but at the same time not accessible. The inner workings are totally hidden. And even for the municipality, there’s nobody to call if you want to do a project with Google. As a politician, there’s nothing you can do. You need to go through headquarters in the US. So to shed light a bit into those processes is interesting …

Carmen: Yeah … I guess transparency is one of the bases of a democratic society, it’s implied that you need to be able to form an understanding through gaining knowledge or information about something to make an informed decision as a citizen. I think within our lifetime there has been a shift. We’re less and less citizens of our environments. We’re more and more just the users who need to work with the rules we’re given. And I think as artists, we have the freedom to question that and to try and push these systems beyond just giving us the little interfaces they give us, and asking the question of why is it like this and do we want to live in this world?

Felix: With that, as much as I like this notion of the Black Box Society—because I think it captures really important things—I’m always a bit hesitant about the term because it has this simple dichotomy of visibility/non-visibility in it. Theoretically, Pasquale makes this case about these layers. I think coming from internet culture, we’re very used to thinking about layers, and different layers have different logics, and different logics allow potentially for different forms of engagement. On the one hand, there is this idea, as you said, of transparency that can create visibility. But on the other hand, there is also this knowledge, or this experience, that behind each layer of visibility there are other layers that are hidden. These are dark and opaque. So it seems less that something is understandable or opaque but that you can illuminate certain areas that give you perhaps a feeling for the depth that you don’t know, that you cannot see. Through this strategy perhaps, or another one, you get another spotlight, but it’s always these zones of visibility and invisibility. I wonder what that does or what it means for an aesthetic strategy. When you use the notion of “art as a perception machine,” it is kind of an aesthetic question of how do you make something accessible to the senses, in this most basic sense of aesthetics. But how do you do that when you know that beyond the thing that you see, there is always a constitutive part of the thing itself that you want to see which is always partially hidden and partially concealed? And the Black Box also has the problem of being dynamic. It’s not like the elevator, which for me is also a black box, but whenever I press the button number two I end up with floor number two. You know, the input/output relation is always dynamic and it’s really hard to say anything about the system, other than its particular state, which might be changed by the time you say it. So I wonder what does that do to the perception or to strategies of creating particular perceptions? Or how do you create the perception for something that you cannot perceive, that you know remains hidden even if you reveal certain things?

Carmen: That’s something we see a lot, with the systems we probe. They change with our probing. This makes working in this field really interesting. Many of our works are open-ended, so we need to deal with a certain loss of control. We have a conceptual approach where we decide to engage with the system and we come up with a way of doing something that we think will produce an interesting outcome. But many times for us, what this outcome will be is not foreseeable. Sometimes we think we’re making visible a certain part of the system, but then something totally different becomes apparent. For example, in our first work, Opera Calling, we bugged the Zurich Opera. We tried to reconnect the closed system of the opera house with the open system of the city by rebroadcasting their audio signal from live performances via the telephone network. Through that work, we learnt so much about the kind of the social norms around the opera, the expectations people have, how the whole cultural funding system works in Zurich. But that was actually not what we wanted to do. We really wanted to update the opera and open this up and find a new way of engaging. I also think for the people listening to the audio feeds at home, it was just very surprising to have this come into your daily life when you didn’t expect it. You pick up the phone, you think somebody wants to talk to you, but then you’re listening to this live performance. But the work also had an impact on the Zurich Opera itself. They suddenly realized that they actually wanted a different connection to the city. That they didn’t actually want to be locked in this little building. Of course, things always stay opaque. I agree, it’s not black and white. It’s kind of surprising what you suddenly get to see. And in the best case, the systems begin to shift. I think art is not good as a solution. It’s good at asking questions. So these are temporary artistic interventions that kind of narrate one singular story or a single moment in this story. But I still think it’s a very valid way of trying to perceive what is going on because just being a user usually gives you no information.

Felix: Yeah, I think this loss of control is something that is almost unavoidable if you want to deal with the system that is complex beyond your understanding …

Carmen: Exactly.

The postman should decide where it goes

Felix: … Even in the case of something that is relatively, as you say, bounded like the opera, like the Opera House. We have a few hundred years of experience of what the opera is, so this is not an unknown system. But, if you see it as part of a larger social-cultural system, you realize, oh, there’s so many layers that you couldn’t possibly think of all of them. And then it almost invariably gets out of your control. Still, you can also use that the way you do it, as a kind of key part of the strategy, so allowing these dynamics to emerge from edges and layers that you don’t even know, but that tells you something about the system. Perhaps not what you asked, but something else that is different. This makes me think of one of your most recent works, Postal Machine Decision, which, I think, is a very interesting set-up, so to speak, or conceptual device. At the same time, it is tightly controlled since it has very few options, actually only two. And it is within a system that is also very bounded: the task of the postal system getting a letter from A to B in a reasonable time frame. Can you say a little bit about the work and what interests you in that particular approach?

Doma: Postal Machine Decision comes from an interest in how work and labour are currently changing in the era of highly complex logistical systems, in which things are produced in China and become available within two weeks in Europe. How does that work? You know, what kind of machine is behind those processes?

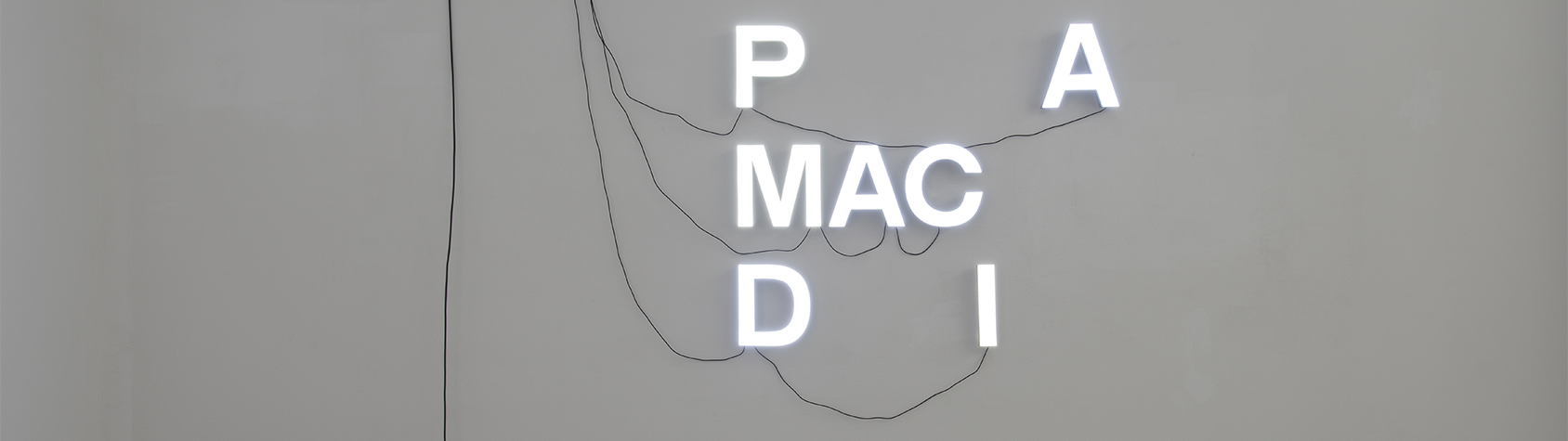

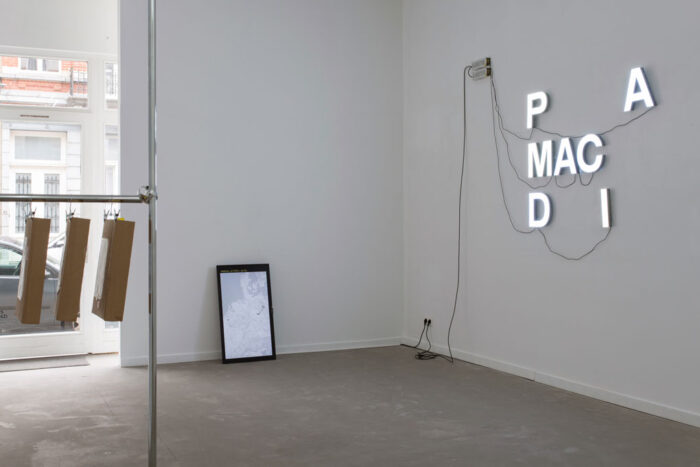

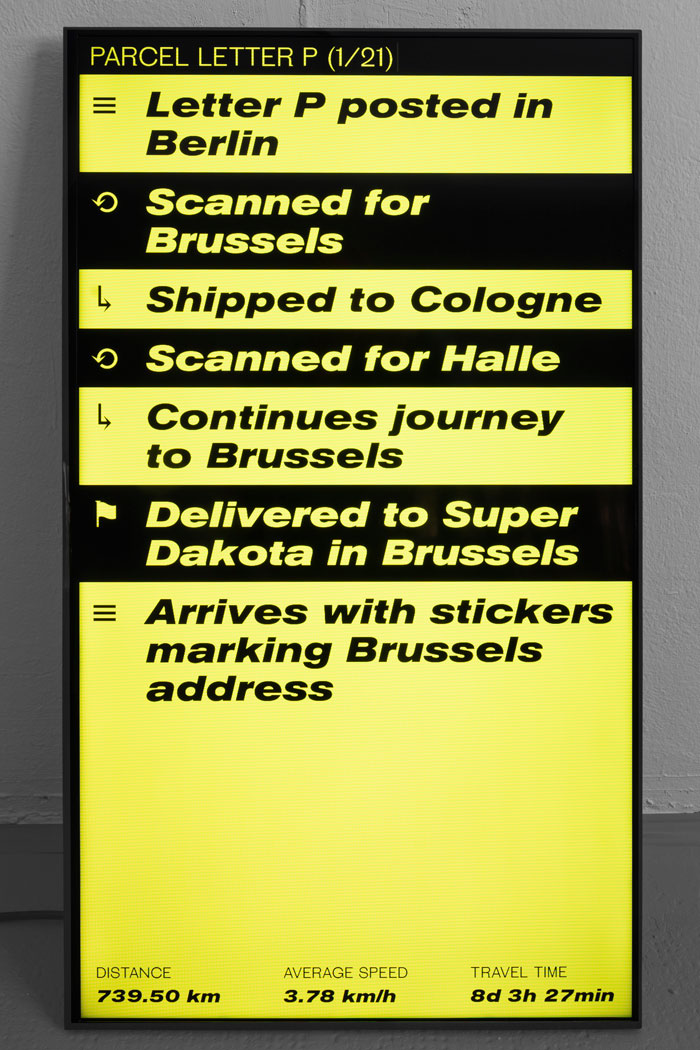

We looked at this from different perspectives. We visited DHL’s big logistical centers, trying to understand how the workforce is structured there and what types of machines are employed. And during this research we kept coming back to an art piece which has always impacted us. It’s The Postman’s Choice by Ben Vautier from 1968. Vautier was part of the Mail Art movement of the sixties which used the mail network as an artistic medium. In The Postman’s Choice, he sent a postcard with an address on each side, addressed to two entirely different people in different cities and left the choice of where to deliver the card to the postal worker. It’s a very beautiful work, because when you think about the kind of agency the postman normally has, there’s nothing to decide. Usually, he’s just a small screw in a machine, he just functions as a robot. And suddenly with this postcard, he gets a choice to make. It’s beautiful to give that agency to a position which normally doesn’t have it. We were really intrigued by the idea of updating the piece from 1968 to 2020. What has changed? Who will decide today in today’s highly automated postal system, where the sorting is not done by humans anymore? Today, it’s the barcode, the computer-readable barcode which decides what route a piece of mail will take and not the postman. We addressed 24 parcels with two addresses each: The first address was an exhibition space in Leipzig/Halle, the second an exhibition space in Brussels. And depending on which side the parcel fell on the conveyor belts in the automated sorting centers, the parcel changed route towards Brussels or Leipzig. So what happens is that it starts to bounce within the mail system. A parcel would take a route and almost be in Brussels, and then it would check in for Leipzig again and just go back. It took weeks for the parcels to arrive at one of the two destinations.

Carmen: It is interesting to observe how logistical systems are shifting from human-driven systems to computer driven-systems. Today, standard parcels don’t actually pass through human hands anymore. They’re automatically sorted by machines. By probing the machines, a map of the logistical nodes emerged. When we did the work for Leipzig/Halle and Brussels, the interesting thing was that all parcels—when they finally did arrive at a destination—had actually all passed through human hands because somebody just got fed up with a parcel that kept bouncing within the system because it had two addresses. So somebody actually went and got it off of a conveyor belt to remove or destroy one of the two labels.

Doma: … or they put stickers on it, saying we are here, we’re going in this direction. What I like about the work also is that we weren’t in charge of what was shown in the two exhibitions because the pieces were transported within these parcels. So we had no idea whether anything would arrive at the exhibition space in Brussels—the first five packages all arrived in Leipzig/Halle. We were like, what if we have an empty show in Brussels and a totally overflowing one in Leipzig/Halle. Yeah, we like to provoke situations, where we don’t know what kind of results we’ll get. And where there’s also pressure involved in it.

Felix: The nice thing about doing this today rather than in the sixties is you have all these moments where the thing is tracked and the follow-your-parcel-type interface gives you an idea of how this is moving and how it’s moving back and forth. But I’m very surprised about what you said now, that at some point someone intervened?

Carmen: Yes.

Felix: Because, theoretically, this could have gone on forever.

Carmen: Yeah, sure.

Felix: Right, ’cause it always looks like a normal package, right?

Carmen: Yes.

Felix: I don’t know whether maybe it creates its own history, so this package may have been flagged. At some point a red flag comes up and somebody has to go down and look it up and see why the parcel is behaving so abnormally.

Doma: The thing is that the parcels sometimes also disappeared entirely from the system. For the postal system, every piece of mail can have only one address. So when suddenly the other side is scanned and the parcel is transported somewhere else, the first address is flagged as missing.

Felix: There must be some kind of error detection. Maybe if a parcel has too many checkmarks, or has gone through seven hubs and usually three are enough to arrive, or when, it’s too far off a standard set of routes. Normally, between these two cities it goes either through that major hub or the other and suddenly …

Doma: You know, sometimes a parcel passed through the same hub three times or four times. So it produced a mess within the system. And I loved reading the tracking information because it became totally absurd. It was total chaos.

Felix: But it seems that if it can pass the same hub several times without raising flags, then the error-detection is not particularly sophisticated. You would expect that already the second time in the same hub should be a major red flag. But maybe not. Maybe there are a lot of these errors anyway. We all know this experience that quite often packages arrive quickly, but sometimes they don’t. Yeah, so maybe there’s a lot just in the normal error rate of misreading, or it falls off the conveyor belt, or somebody who should do something does not. So that the error rate or the inefficiency of the system is so high that it takes a lot of going back and forth for any flag to be raised. Otherwise, it would create endless flags, and then the whole system would break down.

Carmen: This leads me to something that I’ve been wondering about. In the past, a higher level of objectivity has been attributed to algorithmic or computer-driven systems than to their (flawed) human equivalent. Especially when it comes to decision making, computers were often seen to be less biased. And institutions have been known to use this as a defence against blame: It was the algorithm which decided, so the decision cannot be contested. I wonder whether you see that this is currently changing and that people are less willing to accept this?

Felix: I think this is emerging as a major area of contention and there are big fights around that. I think for a long time, the institutions have had a free pass. I would say it’s just a system, it’s just computers. I remember when Google started to scan Gmail to place ads. This was seen as a major invasion of privacy. Oh, now they’re reading our private mail! And they said no, no, we don’t read it, it’s just the algorithm. And somehow that was acceptable. And I think this is beginning to change. That claim is not so simple any more, but it’s still made very often. I mean, there was this big kind of outrage in the UK just recently about the algorithm grading students —because of Corona they couldn’t take enough exams—and creating all kinds of weird, unexpected outcomes. This was clearly part of a kind of austerity in the educational system, and we just do it, you know, we automate all of that, and so it’s a set of political decisions that leads to that point to say, oh, let’s let an algorithm, do it. But what happened? Johnson came and said, this was another, he had a very odd word, I can’t remember it now. I can maybe look it up afterwards, but it was only just a computer malfunctioning. (He called it a “mutant” algorithm.)

Carmen: Yeah, a misunderstanding.

Felix: A computer error, so to speak. Which means, well, it has nothing to do with us. Nobody could have foreseen that. And I think these kinds of strategies are part of this, “Let’s outsource decision-making to computers so we’re not responsible for that, even though occasionally things do go wrong, but quite often they do what is expected.” But dodge responsibility, by either saying, “I don’t know how this happened. The system is proprietary and I just, you know, sent my data and I got the evaluation back.” Or, you can say, “This is all so complex nobody can say who made a mistake.” I think this is strategic. I think this is a way of assuming power but not responsibility. So you can do it, but you’re not responsible for what is being done. And that is an old trick, but I think it is becoming contested now. But for the moment, it seems in this particular case in the UK that, OK, it was a computer error. They always can happen. We all know that, so it was politically neutered, even though it was clearly the culmination of problematic education policies for the last decades. So I think it’s important to go against this myth of the autonomous system. This is another one of those fantasies, like systems are autonomous, so it means that they do it by themselves, which is obviously bullshit. There are no systems that are autonomous, there are systems that have certain decision-making capacity, sure it is relegated, but it is always embedded in an institutional setting and somebody looking at the bottom line and saying, “Oh, this is very profitable and we don’t need to care about errors.”

Doma: Somebody still writes the software.

Felix: Somebody still writes the software. Quite often the people who write the software don’t really know what exactly they are doing. Or the software is compiled out of a lot of different libraries and so on. So I think it’s to develop not only an understanding of these systems, how they work, how they operate, but also how they embed it, how they are not autonomous. I think it is quite challenging, but also quite important because this is really one of the important political fights of the moment.

The honeymoon phase of social media is over

Felix: I think this fight will probably be a long one. One which will go on for the next couple of years. So maybe that is a good segue into another work of yours dealing with algorithms that sort job applications.

Carmen: Yes.

Felix: Maybe you can simply start by quickly describing it. You know, what does that algorithm do and how does it work?

Carmen: This work comes from an ongoing interest in looking at algorithmic systems that have gatekeeping functions. For example, for a number of years now, when you enter the US, you are asked to hand in your social media handles as a way of background checking you. Due to the sheer number of people to be processed, these checks are usually done algorithmically. They’re delegated to a machine which sifts through, say, seven years of people’s social media accounts and looks for certain keywords or certain kinds of behavioral patterns to rate people’s behavior on social media. To look at the way that social media profiles are algorithmically rated, we have been looking at an algorithm that’s used by human resources departments to rate job applicants social media profiles. This is done for two reasons: It’s a fast way to reduce the pile of applications to just a few to be then looked at in-depth. And it is seen as a way of reducing the threat of social media shitstorms directed at the company. Companies want to ensure that the new hire does not pose a threat to the company’s reputation with their private social media posts. Because potentially, today, any single tweet can generate a Twitter shitstorm, and this can reflect negatively on the employer of that person. What we found really interesting is that the companies that sell these algorithms don’t actually disclose how their algorithm works. They use the same strategy as Google and say that the algorithm is their business secret, while at the same time, telling you that they can absolutely predict people’s personality through their public social media data. We ran eleven social media profiles through the standard hiring algorithm to find out how it operates. What exactly do we get back in terms of rankings, in terms of flagged content, in terms of the kinds of personality structures the algorithm attributes to the profiles. And we used the output to generate prints for sweatshirts to also talk about how you don’t know how you are rated, but you still carry it on the outside of your body in a certain sense, because it’s what people see and know about you.

So the algorithm goes seven years into your social media history. It collects all posts, all images which then becomes the basis for the analysis. From this data, the algorithm calculates a sentiment analysis indicating, for example, how somebody felt while posting something. They sift through the content for anything that is politically explicit. Nudity, for example, or bad language is flagged in cases that seem exaggerated. In this, the view on the content is a very Silicon Valley-slash-US American view on content. Many times, looking through the flagged posts was confusing to us, because often we didn’t understand why something was flagged. Maybe there’s somebody in the background of the image wearing a bikini and that’s already enough to flag for nudity. But through trial and error, through feeding it data, we came to understand what kinds of outputs the algorithm produces. However, the companies which employ these algorithms don’t actually look at the details of what the algorithm produces. They run, let’s say, 250 applications through the system. And then they only look at the 15 “best” candidates, but they have no way of actually understanding what “the best” means for this algorithm. This is quite worrying, because this procedure also doesn’t necessarily produce the best fits for the company. The best fits may be in the other, discarded pile, and that is also actually harmful because it does the opposite of what the algorithm should be doing. It was really interesting to look at how also in the employment world these decisions are kind of outsourced and how little oversight there is.

Felix: For me, there are two things that are really remarkable about the world that this work reveals. The first one is that you said that basically everywhere are lots of companies offering these services, but these are shells all leading to the same algorithm(s). So there’s a very small number of algorithms that are doing this. Perhaps only one, perhaps there are a few more, but it’s definitely much less than the number of service providers that seem to be working, for low-end or high-end clients. But in the end, it’s all the same, which indicates that the bias has become really uniform.

Carmen: Yes.

Felix: Obviously, human nature is also super-biased. There are lots of tests, you know, where if you just change the name to a German-sounding name or an English-sounding name or whatever your chances are much higher, so there’s lots of bias in that, but you still have the chance of finding different biases and not being hit by one, but, or getting—

Carmen: or hit by the same one all the time …

Felix:—either you’re always going to get through or you’re always penalised, which makes it extremely difficult to route around that bias. And the other thing I find really fascinating in a frightening way is how primitive the algorithms are in terms of both the psychology and the categories. They employ this psychology from the 1950s that is largely disregarded as meaningless, but it’s very easy to program and to code. But, still, from this, they’ll make very real decisions that impact peoples’ lives in ways that must feel really random, right? You don’t know why, you just never hear back from anyone. There’s no way for you to control that or deal with that. And it’s always the same. It always hits the same people in the same way. That seems to be really, really problematic in terms of having any sense of equal chances.

Carmen: Yes, and what we also saw with the test profiles we ran through is that those algorithms use only the “public data.” But to the people producing it, to the people posting images, this public data, or this publicly available data, might feel very private. So some of these accounts were people posting a lot from their family life, for example, and I’m not sure it’s ethically OK to kind of mix that—

Doma:—with our work …

Carmen: … with a job application process. Where before it would also not happen. Usually, up until now, as an applicant, within certain social norms, you could decide what you were going to tell your future employer about yourself. You wrote your CV, you submitted the photo, and that has kind of changed, you know. People are forced to have more parts of their identity become public in a way. I think that’s also a worrying shift, in the sense that I’m not entirely sure people understand this. And I’m also worried about a generation growing up now that is filling, or starting to fill, their social media profiles at 15. And then 15 years later, you’re applying for a job at 30 and you’re confronted with this whole history of …

Felix: It’s hard to decide what’s worse: that you don’t know that, and then you’re suddenly confronted with your party images and whatnot, which, usually when you used to write your CV there was no space where you had to write how you spend your vacations.

Carmen: Yeah, exactly.

Felix: And now this comes in. But the other thing is also quite scary if you know it, and then you have to kind of curate your private life into

Doma:—towards an algorithm.

Carmen: Yeah.

Felix:—towards an algorithm that has, let’s assume it works, which we know it doesn’t very well, but let’s assume it does, so you have to curate your private life for an algorithm that has the interests of the employer kind of built-in …

Carmen: Yeah, in mind.

Felix: So you always have to, even if you go out, you have to be professional. I think about the pressure that puts on people, particularly on young people. Psychologically this is really problematic. So it’s really hard to decide what’s better, to know it or not, but I think more and more people know it. Yeah, I think that this honeymoon phase of social media is over. And yes, there’s enough stories of people getting fired because they had a drink that evening and posted it on social media.

Doma: What struck me about this relation between the hiring process and software is that it’s everywhere. It’s not only describing or trying to understand your public image, but also the documents you hand in, your CV, the cover letter, run through computers to see if, for example, you are using enough keywords from the job offer. And if you’re not, you’re also part of the list of the less qualified, right?

Felix: At least this part you control.

Doma: You can try.

Felix: The hiring process is a fairly controlled environment, and you know you are entering it. But if it spans your entire life it becomes complicated. Social media is how you connect to your friends and family and whatnot. I think this creates a really kind of schizophrenic situation. Where you have to reveal yourself, but at the same time you have to hide yourself.

Carmen: With this, I think that we’re coming back to the black boxes.

Doma: I also like the term that you coined, which we borrowed from you. Some years ago, you worked around the term of algorithmic regimes: Algoregimes. And we started to use this as a hashtag for stuff we didn’t know how to label. We just used your term. Maybe you could elaborate a bit on the term?

Felix: The term regime refers to political order and usually in a bad way. So you have authoritarian regimes, dictatorial regimes. On a political science level, you could also say a democratic regime, but in everyday language, you don’t really say that. So what we wanted to get at was that these are systems that organize society. That they organize the way we live. And when you look at that from that perspective, the question of whether they are correct or not is not the most important one, because even if they are total bullshit, they still organize your life. Even if the HR algorithm consistently mislabels you in the most grotesque way—it’s still there and if you fall under the threshold you are discarded right away, and you will never know even that. So we should not think, or that was our idea that we should not think, in terms of the veracity of these insights that these produce or accuracy or fairness, even though these are all important things, but we should also think about in terms of the effects. No matter how shitty it is, no matter how good it is, it produces certain types of effects. And these are actually at least as important as the questions of good or bad, whether it’s accurate or not. That was the idea, that these effects create a new kind of way of ordering society for the better or worse. I mean, maybe it’s better and I can see certain instances where perhaps the most obvious racist bias that is distributed in society might be less pronounced in the system, even though we know that these biases creep in through the data used to train these systems. But at least the idea that you could think that it might be better, but still it’s a regime. It’s a way of ordering society.

Doma: Well, I think we should stop here.

Felix: I think we almost filled the reader.

Carmen: I’ll stop the recording.

Felix: Yeah.