Filling the Gaps

In occupied Kashmir

This essay stems from the newly released book by Skye Arundhati Thomas and Izabella Scott Pleasure Gardens (MACK, 2024), an urgent account of the military occupation and internet blackouts in Kashmir, narrated through a log of fifteen days covering the events surrounding the region’s constitutional special status revocation by the Indian government. Archiving the everyday becomes a practice of solidarity and resistance to counter the informational loss caused by the enforced communication shutdown—a practice borrowed from Israel’s colonial strategies.

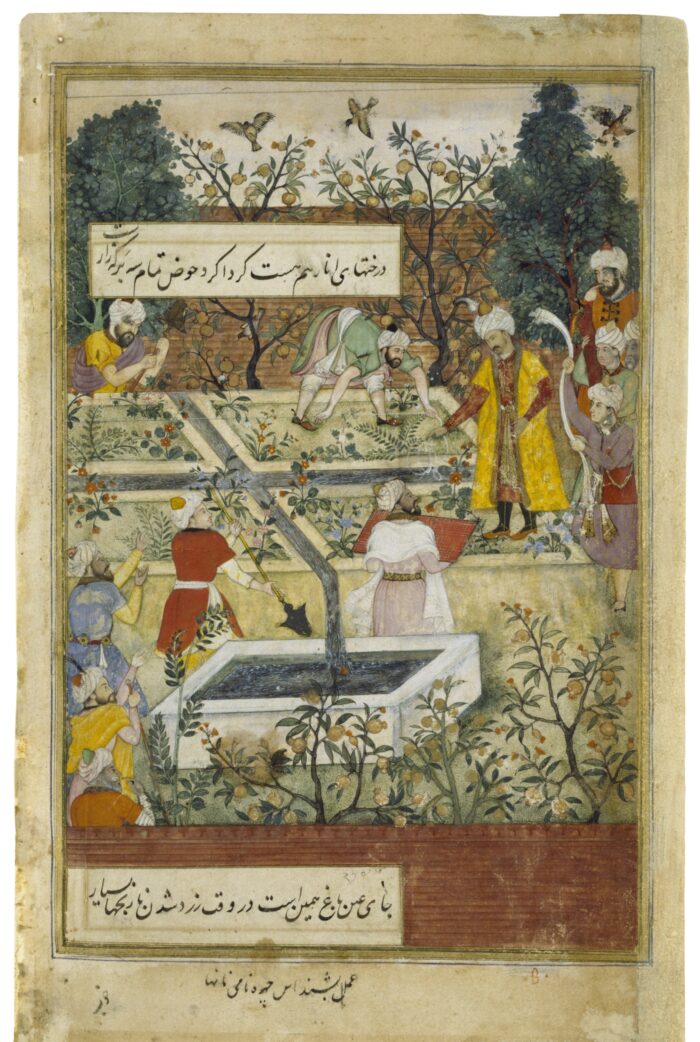

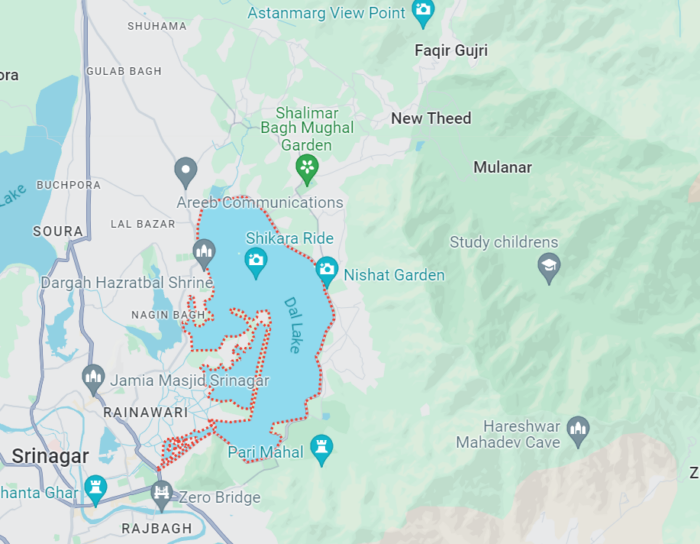

Ironically enough, one of the largest army camps in Indian-occupied Kashmir (IOK) is named after a Mughal pleasure garden: “Badami Bagh,” or “Garden of Almonds.” Between the Pir Panjal and the Great Himalayan Range, in the centre of the Kashmir Valley, there is a lake, the Dal, whose surrounding slopes still bear traces of the ancient orchards.

“…typically, in the pleasure gardens of Kashmir, the garden site is at the lower elevation of a hill, between the hill and the lake. […] The garden celebrates the beauty of the valley. It transcends its visible physical limits, and the internal space engages dramatically with the larger setting…” (Shaheer, n.d.)

Poplars, almond, or Chinar trees; a central water channel sourced from natural springs; an intricate composition of fountains cascading down from one terrace to another; and an elevated space placed over the channels, which finally flow into a water body—in this case, Lake Dal. This is what a pleasure garden could have looked like in fourteenth-century Kashmir and, later, during the Mughal era. But now, at the site of Badami Bagh, “soldiers in military fatigues rest, strategise and train within the camp’s perimeter,” describe Skye Arundhati Thomas and Izabella Scott, “[it’s a] place where the disappeared were seen before they disappeared, a space of dark deeds.” Thomas and Scott are the authors of MACK’s newly released book Pleasure Gardens: Blackouts and the Logic of Crisis in Kashmir, a visual and textual investigation into the military occupation and communication shutdowns in Kashmir, a heavily militarised region and a decades-long battleground between India and Pakistan.

Part of Pleasure Gardens is an attempt to fill in the informational gaps surrounding the days when Kashmiri constitutional rights were revoked and the state was deprived of its special status. Thomas and Scott’s essay meticulously collects and archives information at risk of being forgotten or neglected, given that the events unfolded during a 213-day communication blackout enforced by the Indian government in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). In August 2019, during the Amarnath Yatra season, a Himalayan pilgrimage, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi started to build up collective alarmism on the grounds of an alleged climate of instability in J&K that could favour the organising of popular insurrections. It all started with a massive increase of Indian armed personnel in the region, followed by the circulation of an official document issued by the Indian Railways claiming the deterioration of public security in the Kashmir Valley that served as a pretext to enforce a curfew on IOK and a state order to evacuate pilgrims and other visitors.

On August 4, the Indian government blocked all telecommunications, including internet access. Despite the lack of revolt or insurgencies, the Indian Army acted like there was one. The day after all communications were cut, Modi’s government passed a bill revoking Articles 370 and 35A, the only constitutional caveats that used to give J&K a glimpse of autonomy and statehood. Articles 370 and 35A—the first setting J&K’s right to have its government and laws, the second allowing J&K to define its permanent residents—were established in 1947 to set J&K as a partly autonomous territory when the Union of India gained independence from the British Empire. Revoking them, especially Article 35A, had crucial consequences on who could settle in Kashmir, buy land, and vote, thus “paving the way for Israel-style settler colonies.” Thomas and Scott report the events as witnesses, creating a log of the first two weeks of August that starts by reconstructing broader political events and gradually narrows the archiving process down to everyday life during the blackout under the intensified military occupation.

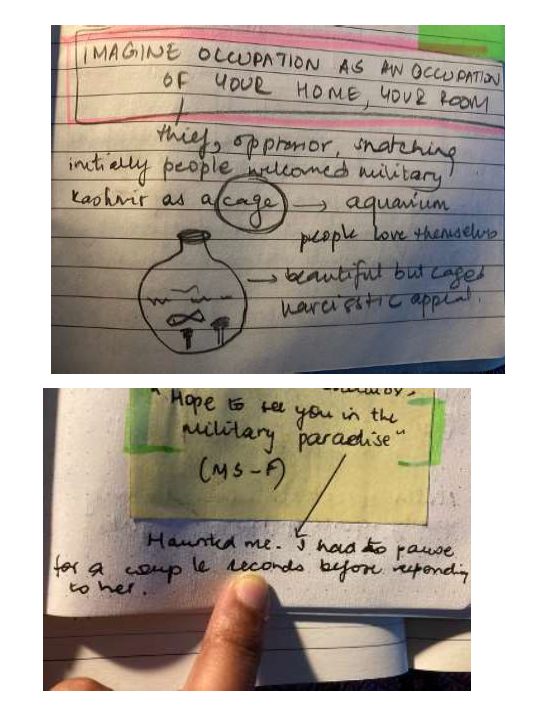

Co-writing and everyday archiving was a meeting place of solidarity and resistance also for Indian and Kashmiri researchers Niharika Pandit and Samia Mehraj. In the collaborative process that led to the publication of their paper The Ghosts That Haunt Us: (Anti)Colonial Residues and Feminist Solidarity in Everyday Archives, Pandit and Mehraj assembled reflections, conversations, reporting of banal encounters, and visual and sensory narratives in response to what they identified as “a lack of sustained and solidaristic engagement between Kashmir and India,” in the hope to “find in [the] archives moments of reparation.” Reflecting, directly and indirectly, on the implications of their colonial history on the hate and violence integral to the occupation in Kashmir, Pandit and Mehraj think about colonial ghosts that never really left and that are now coming back to haunt the region and its inhabitants. Fueled by the urge to collect all that remains of a disappearing Kashmir, Mehraj “records sounds of pebbles, rain, and rushing Jhelum, [her] parents speaking about their best memories and their worst fears, […] the cows of Kashmir, the solitary vendor who shouts out in the morning, the herds of sheep that pass silently at night.” Everything besides the sound of guns blazing at night. With the prolonged and increasingly frequent shutdowns, archiving feels more urgent than ever.

Communication blackouts imposed by governments are a severely disruptive strategy of surveillance. From fully restricting internet access to slowing it down significantly, shutdowns prevent citizens from accessing and sharing information in critical moments when the ruling party needs to control knowledge production and circulation; for instance, before enforcing major political decisions that rescind constitutional rights. This is what happened to the Kashmiri population in August 2019, when the Indian government entirely shut down all communication networks in J&K right before Modi revoked the region’s constitutional semi-autonomy, dividing it into two federally governed territories. Allegedly, the measure was taken to prevent organised uprisings, arguing that social media and mass messaging have previously incited violence in J&K and that imposed restrictions would therefore save lives. Practically, the Indian government’s first concern was not exactly to spare Kashmiris’ losses. Blocking landlines, fixed-line internet, and mobile networks works as a strategic triple barrier: it hides accurate information about the unfolding political situation; prevents the population from forming a collective response on social media; and dangerously limits journalists’ ability to report from the affected regions, thus controlling what news spreads worldwide.

Disrupting digital mobility is disproportionately harmful to a population that relies heavily on online services, impacting fundamental areas such as healthcare, businesses, and education. The shutdown’s collateral effect of protractedly damaging the health system, the economic sector, and the youth’s prospects is instrumental in reinforcing control over occupied territory. This control is directly proportional to weakening the country’s autonomy and, therefore, its long-term capability of resisting internally and externally by diminishing its international reputation and relevance. Seizing communication access from a population is thus viciously infantilising and, by law, a human rights violation, especially if the measure is purely manipulatory and lacks a concrete pretext of a precipitating offence. But the Indian government has a soft spot for telecommunication shutdowns, abusing them to the point of setting a world record since 2018. The complete blackout on fixed-line internet and mobile networks in J&K persisted for almost 213 days, while the shutdown of fast internet access lasted even longer, extending for 550 days until February 2021. According to the government, this is legitimate on the basis of the Telegraph Act, which allows authorities to block internet services for public safety reasons, including to maintain the sovereignty and integrity of India.

This is just one macro-level observation of India’s infrastructure of surveillance and occupation of J&K, which, as Pleasure Gardens’ authors Thomas and Scott remind us, alarmingly mimics Israel’s occupation of Palestine in many ways. Historically, India’s and Israel’s births as nation-states are close in time, in 1947 and 1948 respectively. Initially, their trajectories were oppositional: India aligned with the Arab struggle in seeking independence from Britain, while Israel relied on British power and influence to establish its state. However, soon after, the need for arms deals to address disputes with China and two wars with Pakistan drew India closer to the Zionist project, shifting the initial alliance and laying the foundations for a long-lasting collaboration. Following 9/11 and the rise of the “War on Terror,” both countries leveraged America’s Islamophobic agenda to their advantage, integrating it into their state propaganda.

Islamic extremism thus became the new framework for addressing issues in Kashmir and Palestine, justifying military occupations and any sort of violence in the name of the American motto of self-defence. The situation escalated until 2019, when, alongside the revocation of J&K’s constitutional special status, the Modi government delegitimised Muslims as citizens of the Indian nation-state through The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Among the atrocities committed by India and Israel on the occupied territories, attacking telecommunication infrastructures has been a common thread. From 2002, when Israeli soldiers violently shut down the operations of the Palestinian internet service provider Palnet, to October 2023, when the Palestinian Mobile Company announced the complete interruption of communication and internet services with the Gaza Strip following the Israeli aggression, the blackout persists to the present day.