Falcons As Subjects, Not Metaphors

A conversation between Veronica Pecile and Elisa Caldana

Up until 3 May 2025, the MACTE Museum of Contemporary Art in Termoli hosted the exhibition The Falcon of Karachi by Elisa Caldana, created thanks to the support of the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity as part of the Italian Council programme (2023).

With this series of works (film, sculptures and a set of textiles), developed by Elisa Caldana over the course of two years with the help of collaborators both in Europe and Pakistan, the artist explores the relationship between wildlife and domestication and the processes that are triggered when wild nature is forced into captivity. The laggar falcon thus becomes a metaphor for reflections on power relations and pollution, but also for focusing on human rights and those of non-human entities.

The installation designed for MACTE reproduces the atmosphere of a courtyard in Karachi, in particular the falconer’s home, creating a space in which the works interact with each other and with the visiting public. The bronze sculpture Untitled (Released) shows hands holding a falcon the moment before it is released into the wild: leaving a permanent trace of a moment of liberation that lasts the blink of an eye.

This is followed by a dialogue between Elisa Caldana and Veronica Pecile, a researcher who investigates the relationship between law, time and subject with an interdisciplinary approach, focusing on legal means by which to represent non-human entities and non-linear temporality.

Veronica Pecile: In your video works, you make visible the paradoxical situation in which the laggar falcon lives, a condition poised between the wild and the tame state. This hybrid state for me reflects a symbolic level. In a book entitled Animal Presence, the philosopher and psychoanalyst James Hillman explains that in ancient bestiaries birds are described as being born twice: first as an egg, from the mother, and then from the egg itself. These animals thus participate in two worlds: a higher, divine one—in ancient Western philosophy they are messengers sent by God—and a lower, material one. Birds are manifestations of the intellectus agens, the “high” active intelligence that descends into the human sphere. How have you represented this dual nature of birds—wild and domestic, aerial and terrestrial—in your practice?

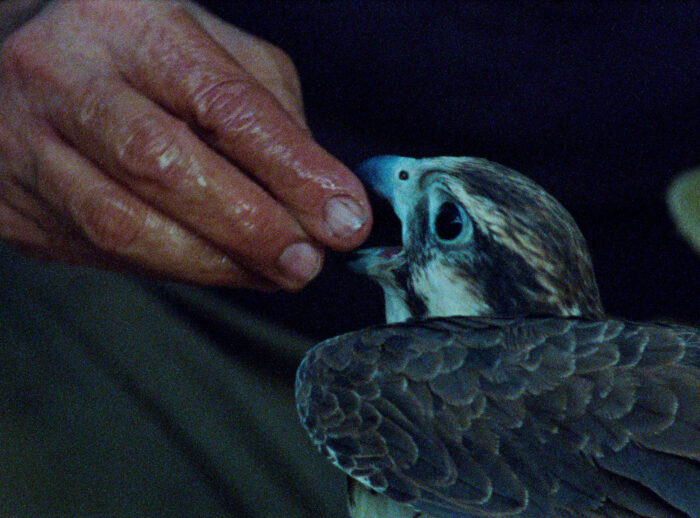

Elisa Caldana: The Falcon of Karachi concerns the laggar: a falcon endemic to Pakistan, India, and Myanmar. It was once the most common falcon on the Indian subcontinent, but today it is in sharp decline. I was introduced to it by some European falconers—engaged in breeding laggar falcons in captivity in Europe—as an unimportant falcon, of little economic value and negligible from an aesthetic and performance point of view. Fascinated by this introduction, I tried to get closer to wild laggars in Pakistan. My work was mainly carried out in Karachi: the film follows the rehabilitation period of some laggars in the homes of local falconers, from the moment they are saved from the animal market up until their release. The camera portrays them, lingering on close-ups, in moments of transition between opposing worlds: domesticity and wildness, captivity and freedom, sleep and wakefulness, life and death. Conditions that shape their identities as birds of prey and their behaviour.

Veronica Pecile: I’m struck by the fact that you chose to focus on a “minor” bird, one that is considered by humans to be neither valuable nor productive. This seems to me to be an exceptional situation compared to the binary relationship that human beings have established with nature during the modern era, a relationship that tends to take the form of either protection or exploitation. Ultimately, these are two sides of the same way of thinking—of considering animals, plants and ecosystems as an “other” with respect to humans, to be absorbed in a logic that is either one of profit or of monumentalisation. To establish this binary relationship, in which nature is in any case no more than an object to be exploited and valued, a series of tools and knowledge are used, including legal ones. What we call “nature” is basically an artifice, a construction produced and reproduced through law and other techniques. The relationship between the laggar falcon and the human communities it narrates seems to stand outside this narrow way of imagining and regulating the natural world. And perhaps it can offer a number of answers to some key questions: how can we live in the ruins of capitalism? How can we re-institute nature to establish a logic not of profit but of social and interspecies cooperation? [1]

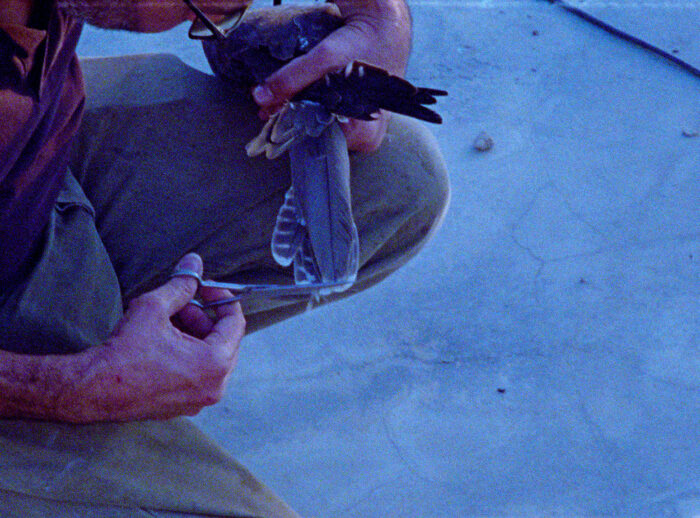

Elisa Caldana: Laggars and the human communities linked to them further complicate the space between exploitation and protection, especially because the laggar is not the focus of the common imagination. Its decline goes unnoticed, as happens with other less visible species, deemed of minor importance. At the same time, the lives of these falcons are intertwined with those of the ones who exploit them, for example using them as bait to capture more valuable falcons to resell for profit. It is a web of interdependencies: in certain circumstances, the falcons depend on humans to survive, and anyone involved in the commercialisation of falcons depends on them to survive. In this context, the laggar—a falcon traditionally used as a decoy and considered expendable in the capture of more valuable falcons—suddenly takes on ecological relevance. In the development of my work, I collaborated with falconers turned rehabilitators who use traditional falconry techniques to preserve the wild nature of the animal, supporting birds of prey to set them free instead of exploiting them and turning them into property. The film looks at the falcons as central and predominant figures, while the human presence emerges exclusively from their hand gestures.

Veronica Pecile: In your films, you don’t use dialogue or voiceovers so as not to impose any human point of view on the animal. There is a part where people fix the feathers of a crow on the body of a falcon that can thus return to freedom, assuming the identity of another animal and becoming a sort of hybrid. [2] This scene makes me think about the big question of the representation of the subject in modern Western law. In the ’70s, legal philosopher Christopher Stone proposed to extend the status of subject to forests, rivers and entire ecosystems. Today, with the so-called “rights of nature” recognised in numerous constitutions, laws and rulings, his vision seems to be becoming reality. A well-known example is that of the Whanganui River in New Zealand, which was granted legal personality in 2017 through the establishment of a committee of individuals who represent its interests in court. These developments are interesting because they demonstrate that legal thinking is changing, but they are still fictions that, when all is said and done, do not challenge the actor at the heart of modern thought: a white, bourgeois, property-owning male subject who builds a relationship of subordination and exploitation with his “other”—a non-white object, assimilated to nature and to the feminine, to be colonised and dominated. In short, extending legal personality to entities in the natural world is perfectly compatible with the continuation of capitalist exploitation; indeed, it can become a useful discourse to legitimise it. For example, in the United States it was decided a few years ago to eliminate the protection of birds in the case of events such as oil spills at sea, which are now categorised as accidental events for which oil companies are not held responsible. How can we escape from this paradoxical situation in which we live in an era of extreme exploitation of resources and at the same time are dominated by discussions that call for more and more rights for “nature”? What does the story of the laggar falcon teach us about those who live outside the logic of profit and, more generally, about radical ecological thinking?

Elisa Caldana: It highlights how the radical environmentalist perspective is inseparable from a class dimension. In Pakistan, I heard stories of trappers capturing wild falcons to resell them, camping out for weeks waiting to catch a high-value passing falcons (mainly saker and peregrine falcons). Many of them have no alternative means of support, as they live in remote locations and survive on less than one euro a day. This practice, handed down for generations or learnt via social media, represents a source of income that can guarantee the sustenance of their families for up to a whole year. Although there are laws, they are ineffective because they do not address the underlying problem that pushes these isolated communities to go into debt to capture falcons and sell them on. Many operate outside the law or in areas where regulations are not practically enforceable due to a lack of resources. Furthermore, local legislation seems to favour foreign buyers with exceptional permits, belonging to higher social classes and with economic power, such as Arab dignitaries, for whom falcons are a symbol of social status. The laggar falcon case highlights the importance of concrete actions that benefit the entire biological community involved. For example, by empowering local communities and supporting alternative income opportunities, independently of the exploitation and decline of the species we intend to protect.

Veronica Pecile: It seems to me that there is also a strong colonial element in the story of the laggar falcon. The main subjects involved in this story, besides the falcons, are Pakistani and English falconers. Pakistan, India and Myanmar—all former British colonies—are the main countries where the laggar falcon is found in the world. Then there is the fact that falconry in modern Europe was mainly practised by the nobility, linked to the courts, and this association of the activity with belonging to a privileged class persists today. How did you come across the colonial dimension in the reality you observed and how did you position yourself in relation to it?

Elisa Caldana: I recognised a colonial dimension in the idea of breeding laggar falcons in Europe and then reintroducing them into Pakistan, instead of supporting the conservation of local wild populations. This approach externalises the management of the subcontinent’s fauna, as if conservation depended on European intervention. A group of falconers in Europe wants to create a gene pool of captive laggars, but these specimens, having been away from their habitat for generations, would struggle to survive in the wild. Furthermore, reintroduction does not solve the real causes of the decline and imposes management models that ignore local knowledge, projecting divergent conceptions of wildness. I encountered opposing perspectives: European falconers ready to act for the conservation of the species and Pakistani falconers who consider falconry part of their history and do not see the need for external intervention. This led me to question not only who has the right to conserve the laggar, but also how to create conservation practices that respect local knowledge without reproducing colonial logic. It’s a question I’m still reflecting on.

Veronica Pecile: To conclude, I would like to ask you a question about the “animal turn” in contemporary art, in which animals are increasingly involved as users or means of artistic practice. What do you think its aesthetic and political significance is? Is it a profound rethinking of the relationship between humans and non-humans, or is it just window dressing? This brings us back to the question we were discussing earlier, namely that there can be no ecological thinking without a radical critique of capitalism and its structures of oppression—which affect class, race and gender, as well as—obviously—the non-human realm.

Elisa Caldana: I believe this need stems from the necessity to recognise them as subjects. Acknowledging rights and perspectives that are not exclusively human invites us to reflect on how to tackle the current ecological emergency in a more effective way. For me, The Falcon of Karachi represents both a starting point and a source of disillusionment. I grew up assisting my father at a rehabilitation centre for injured birds of prey, where we would care for these wild animals before releasing them back into the wild. This experience allowed me to find common ground with the falconers of Karachi—sharing the process of rehabilitation and release of the falcons—and to reflect on different kinds of relationship with the wildness and its conservation. In Karachi, I observed how the conservation work carried out by local people is considered a “labour of love” even by the law—a commitment that does not generate profit, carried out by independent falconers or marginalised communities for the sake of dedication and sacrifice alone. I find it contradictory that, while recognising the emergency, the law and institutions do not value the commitment of local actors, relegating them to simple “caretakers” or “birdkeepers,” ignoring the sensitivity, culture and tradition that make their practice possible, one which, in turn, is disappearing. At the same time, it may also be that an ecological emergency is exploited by opportunistic organisations which, although legitimised by law, maintain or amplify the state of emergency and the crisis of animals at risk instead of offering any concrete benefits. There seems to be a gap to be bridged, even in environmentalist thinking, between noisy and self-referential propaganda that capitalises on the emergency without offering real solutions, and concrete actions that are invisible and silent, precisely because they generate neither economic profit nor status.

[1] See Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princetown University Press, 2021; Yan Thomas and Jacques Chiffoleau, L’istituzione della natura, Quodlibet, 2020.

[2] This is “imping”, a traditional falconry technique.

Elisa Caldana’s exhibition The Falcon of Karachi was made possible thanks to the support of the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity of the Ministry of Culture as part of the Italian Council programme (2023). The project was produced in part with the support of the Mondriaan Fund, promoted by the Jan van Eyck Academie (Maastricht), in collaboration with Vasl Artists’ Association (Karachi), West Den Haag (The Hague) and SIC (Helsinki).

The exhibition at the MACTE museum in Termoli, the destination of the works, was held from 14 February to 3 May 2025, and was curated by Caterina Riva.