Faces and Places

Nomadic Subjects in Pictures

Nomadic Subject is a publication accompanying the homonymous exhibition, that for the first time collects the images of five Italian women photographers—Paola Agosti, Letizia Battaglia, Lisetta Carmi, Elisabetta Catalano, Marialba Russo—from the mid-1960s to the 1980s, to convey different perspectives on the experience, representation and interpretation of feminine subjectivity in a period of sweeping social change for Italy. Years of transition from radical political engagement to hedonism, years of terrorist violence but also of civil achievements, brought about mostly by women and the struggles of feminism.

The title of the exhibition refers to the ground-breaking anthology of essays by Rosi Braidotti Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory (Cambridge: Columbia University Press, 1994), in which the philosopher outlines a new sexual subjectivity that is multiple, multicultural and stratified, like the subjectivity represented in the images of the photographers included in this show. This essay was commissioned for this publication.

They look out at you proudly. And their gaze—at times head-on, more often sideways—makes you think back upon yourself. Both reflective and reflexive, these visual images function like prompts. They interrogate the viewers. The pictures engage with our own expectations, mobilize our inner intensity and encourage us to think harder, think further, about our identities. Do we really ever know how much a body can take? Photography of this kind is an experiment with the cognitive as well as ethical powers of art.

Singular figures, even when gathered in groups, these images play a broad affective scale. They alternate between representing individual processes of mourning and celebrating collective scenes of joyful revolutionary energy. I found it illuminating, touching and thought-provoking to survey the photos of the exhibition Soggetto nomade. Identità femminile attraverso gli scatti di cinque fotografe italiane. 1965–1985, held at the Centro per l’arte contemporanea Luigi Pecci in Prato. They are the nomadic subjects of our times, and I was grateful for how they connected to and resonated with my own work.

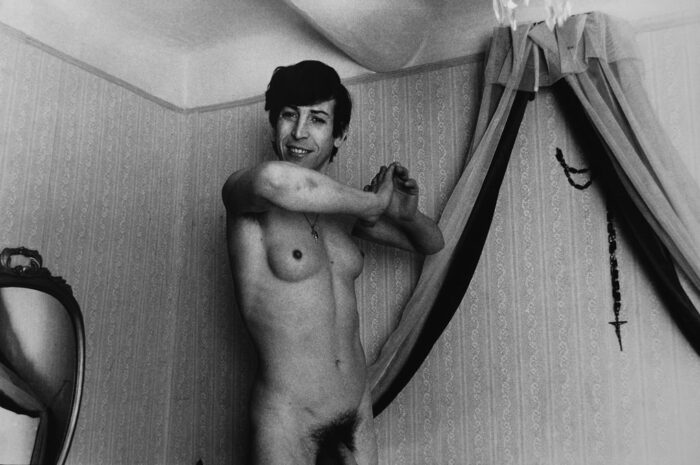

These pictures make a striking statement about the complexity and the contradictions of our times. Even more importantly, they stress the importance of diversity and heterogeneity as the factors that modulate the different ways in which we are becoming-nomadic. The nomadic way is non-linear and non-homogeneous and proceeds through multiple zig-zagging lines. The nomadic subject undoes all simplistic binary oppositions. To imagine, for instance, that two genders alone (M/F) could contain the complexity of human sexuality is a serious but also sad mistake. Sexuality is a transversal force that acts before, beneath and beyond the reductions of the patriarchal gender system. Sexual differing is a multiple process by which all entities split, mutually differ and yet gravitate around each other. We are composed not by one, or two, but a thousand little sexes.

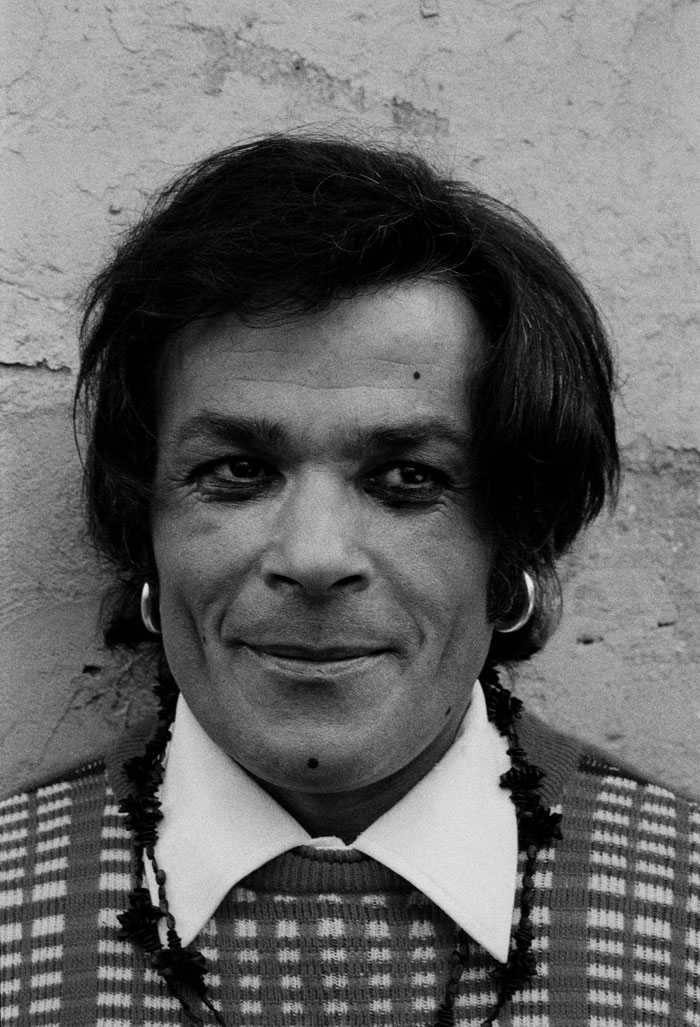

What I love most about the work of these five remarkable artists is the extent to which they foreground a vast array of situated, socially and culturally differentiated subjects, many of whom are feminist, trans and LBGTQ+ people, caught in relations of intensive social interaction and technological mediation. These images document the emergence of nomadic subjects of today. In this respect they are affirmative and joyful, even when they display the pain and hardship of their embodied differences.

Rome, 24 March 1976. Casa delle Donne. National meeting of Feminist groups on family support centers. © Paola Agosti.

Embedded and embodied locations

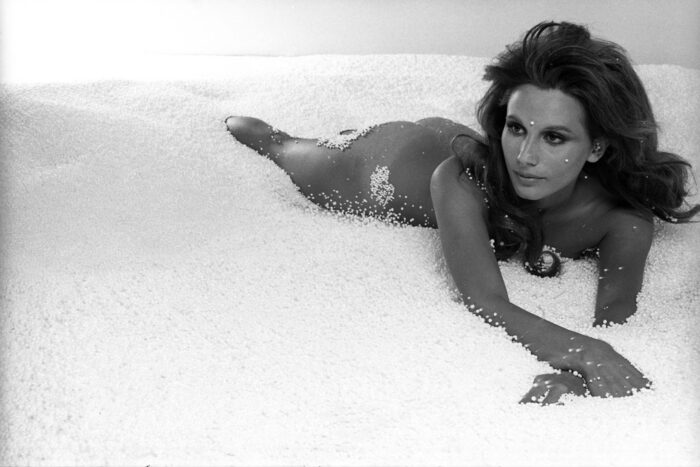

The idea of nomadic subjectivity emerged in my work from the conviction that many traditional points of reference for our self-understanding and many conventional habits of thought about being human are being re-composed in these times of technologically-mediated accelerating changes. The images of this exhibition display quite openly the increasing social stratification in terms of status and access to the technological benefits of advanced capitalism. Polarization of resources and internal social fractures abound and multiply around us, creating cruel contradictions. Thus, some of the exhibited photos are glamorous (see Catalano), others more realistic (see Battaglia). The disparities in power and access they express make for insurgent images (see Agosti and Carmi), but also for introspective and mournful ones (see Russo).

Nomadic subjects are situated amidst knots of social and personal contradictions. Their location is paradoxical in that they are caught in processes of deep-seated transformation, but still struggling with ancient power relations, which far from disappearing, are actually exacerbated in the new socio-economic context. Times are definitely changing and at such times more conceptual creativity is necessary, and more theoretical courage, in order to face the challenges, grab the opportunities and heal the injustices of our economic and social systems. It has become my mantra that we need to learn to think differently about the kind of subjects we are in the process of becoming. “We” are neither One, nor the Same, because we differ from one another. The nomadic subject is therefore embodied but also differential and inter-related.

Far from being a new universal metaphor for the human condition, nomadic subjects are very specific instances: they are embedded and embodied relational entities. Just look at the photos in this exhibition to see the singularity and situatedness of these nomadic subjects, as in the clusters of collective political activism in Paola Agosti’s portraits of the 1970’s feminist movement. Or look at the questioning gazes of the trans-subjects represented collectively, in groups, through the lenses of Lisetta Carmi. Or take in the more individual, but not less social or far-reaching portraits of famous women by Catalano, and of men exploring and exposing their feminine dimension by Marialba Russo. To be a nomadic subject means to be all these possible variations of unprogrammed subjects: they are embedded and embodied, relational and affective, but they differ dramatically from each other.

They are variations on a common human matter, but they modulate it differently.

Each of the subjects represented in this exhibition traces an itinerary through a grounded spatial and social location. They also express different degrees and levels of intensity, desire and disposition to resilience. They are not nomadic in the same way, or to the same degree. Diverse and heterogeneous, these nomadic subjects invite a qualitative critical shift in our ways of thinking about how embodied and embedded subjects are moving in contemporary space and time, across multiple power locations. They encourage us to account for such lived diversity, through materially and historically grounded analyses of the differential locations they inhabit. These differential material accounts allow for resistance to what is always a politicized regulation of space and movement. They call for critiques of power as an on-going process of distribution of entitlements, freedom and degrees of social visibility.

Faces

As this exhibition shows, nomadism stresses the bodily roots of subjectivity. Embodiment is to be understood as neither a biological nor a sociological category, but rather as a point of overlapping between the physical, the socio-symbolic, and the affective. Being embodied and embedded introduces heterogeneity and diversity at the core of subjectivity. This is a way of stressing the materialist, vital groundings of human subjectivity, which include a strong sense of dynamic interaction. Embodied subjects are differential assemblages, multi-functional and complex transformers of flows and energies, vectors of affects, desires and collective imaginings. Moreover, nowadays our complex embedded and embodied subjectivities are also mediated by popular media, celebrity culture and regimes of visualization.

It is not because it is ‘advanced’ that capitalist power must be understood as a sophisticated system: it is, in many ways, a disarmingly simple one. It has to do with the inscription of bodies into power relations in an all-encompassing manner that involves both social structures and personal affects, as well as unconscious desires. A crucial element of the effectiveness of capital are the powers of visualization, recognition and re-presentation that it mobilizes in the social space and their effect upon our social interaction. Public faces spell the regimes of power, and media culture has elevated the glossy commodification of images of desirable—mostly white-females—to the status of glamorous icons, as Elisabetta Catalano’s work shows.

But feminist critics have also been among the first to expose and critique the seduction of the image of power embodied in the visions of subject who represents the dominant norms and aspirations. Faces as landscapes of power are efficient instruments of governance, domination and exclusion. The faces of celebrities—recognizable and hence familiar—accomplish the branding of the star as the commercial product and the self as the individual consumer. Face recognition in popular culture celebrates the union of visual commodities and their consumers as profit-generating entities circulating in a socially enforced circuit of power. Media culture marries the individual to a market economy that sells immaterial gods.

The art of photographic portraits exposes the political economy of different faces as ways of framing and codifying power relations within media culture. Some cultural and political codes—race and ethnicity, whiteness, gender, class, able-bodiedness, beauty—function as passports to normality. Normality is measured by degrees of sameness with the dominant vision of the “right” face, for instance white, powerful, self-entitled heterosexual femininity. This image conveys a standard norm about being subjects: white, able-bodied, heterosexual, speaking a standard language, owning the land, the property, the families and the children, the nation. This is the kind of human that passes as normal or dominant. Such faces express privilege and seduction, while remaining subjected to functionality and commodification. If normality is defined as the zero-degree of deviancy, possessing the “right” face is a social process of becoming a dominant subject that functions by binary exclusions: is she black or white? straight or LBGTQ+? Male or female? Subjected to or the subject of? The face is the landscape that defines power relations.

Compare the portraits of Elisabetta Catalano to those of Lisetta Carmi to measure the distance between the iconic faces of commodified normality and the defiantly subversive faces of trans-subjects. The lived experiences of the latter interrogate the boundaries between the normal, the beautiful and the ethical. They draw dramatically different landscapes of power. Once the images become collective, representing groups and actions, a creative tension emerges between the individual identitarian claims of political subjects that are grounded in the historical experience of oppression, like feminists, LBGTQ+ activists and trans people, and the aspiration to a redefinition of our shared humanity through collective processes of change. This shows a creative tension between recognizable faces and anonymous masses. Between the high visibility and the potential despotism of the One and the facelessness of the multitude. This tension is creative in that it can produce an explosion of energy, of shared joy in the overturning of constricting models, which the photos of Paola Agosti relay with almost infectious force.

The challenge for radical politics today is how to achieve visibility while escaping the effects of power in the age of hyper-mediation, global economics and increasing social injustices. Look at the images of Letizia Battaglia to get a sense of the powerlessness, the fear and the anger of the dispossessed. But then look at the calm resolution of Lisetta Carmi’s faces, and wonder also at their power of resilience and endurance. In the pursuit of points of exit from paralyzing commodification and all-invasive technologies, the exhibition shows the variety of new figurations for these subject-positions. This results in the elaboration of alternative images of the subject, which displace the dominant vision or visualization of power.

To break open the binarism between the recognizable ONE and the nameless MANY, nomadic feminism has invested the potency of ‘ANY-ONE’. The cross-cutting power of nomadic subjects as multiply resisting bodies in all their variations. They are the embedded and embodied desiring subjects who can become the site of unexpected resistance. You sense this transversal force cutting across, its sexual charge as well as its pain, in the group scenes captured by these artists.

Flows and powers

Thinking nomadically is a critical reflection of and response to very specific historical conditions, namely the different locations and speeds of mobility of people, images, data, capital and information in advanced capitalism. The critique starts with the analysis of the instrumental ways in which capital profits from controlling different forms or flows of mobility. These flows are on the one hand virtual—notably through digital information networks and platforms. On the other hand such flows are all too real, through social segregation, migration, security and surveillance. In fact, the dense materiality of bodies caught in the massive infrastructures of global cities flatly contradicts advanced capitalism’s claims to being ‘immaterial’ or ‘virtual’. Digital technologies are intensely real and material. Movements and borders, free circulation and check-points, fluidity and walls, the global city and the refugee camps, are not dialectical opposites, because they coexist in our world. Such juxtapositions express the schizoid political economy of advanced capitalism.

Because advanced capitalism is a system of highly politicized regimes of mobility, I have always been careful to turn nomadic subjectivity into a critical tool to make qualitative differences between the opportunistic forms of flows, the forced displacements and the heady accelerations of economic globalization and qualitatively transformative movements. It has become manifest that goods, commodities, capital and data circulate much more freely than human subjects or, in some cases, the less-than-human subjects who constitute the bulk of asylum-seekers and unregistered immigrants of the world.

I insist therefore that becoming-nomadic is not exactly a glamorous state of jet-setting—integral to and complicitous with advanced capitalism. The nomadic subject, as I see it, designates subjects in movement, changing and disrupting established patterns. As a counter-model to the profit-minded modes of action of capitalism, nomadic subjects signify the transformative desire to become otherwise—that is to say to believe in change and transformation. Nomadic subjectivity assumes the decline of the traditional subject. Indeed, all the photos exhibited here are transgressive, iconoclastic, transformative—even disturbing at times. They take nothing for granted and visually take us by storm.

Power is at work everywhere. The diverse forms of mobility at work in advanced capitalism express different degrees of bio-political management and necro-political governance of contemporary bodies. Look at the photos of Letizia Battaglia so as to appreciate the complexity of a situation that can be too hastily re-packaged as that of the “victim”. There is much more going on in these images of squalid poverty and inveterate pride, inhumane violence and unshakable resilience. Or rather, there is all that, plus the capacity to evoke the desire for change through patterns of becoming. Nomadism is about critical re-location, it is about becoming situated, speaking from somewhere specific. Hence, nomadic subjects are well aware of and accountable for the particular locations they inhabit. Thinkers who are identified with undifferentiated universals cannot live up to this challenge. But artists can. That is why these photographers do live up the challenge of representing the contradictory patterns of change of contemporary subjects.

The question of embedded and embodied locations cannot be separated from the issue of diverging differences. I have argued in my work on the nomadic subject that being in movement can mean so many different things. Again, this exhibition gives us the measure of this diversity: nomadism pertains to highly specific geo‑political, social and historical locations. Being transformed into a movie or TV star, for instance, and thus becoming integrated into the circuit of visual and technological mediation is one kind of change. One that is integral to the profit-making logic of the market economy, but within it makes room for some progress—mostly for young, white, beautiful women. Other movements take us in very different directions: migrants; refugees marginalized social subjects exposed to exploitation and violence—mostly non-white women, children and trans people. Each of these locations comes with faces and places. It inscribes different subjects into differential patterns of movement and transformation. Each of them expresses a different history, with specific patterns of belonging which are marked on the bodies of the subjects that inhabit these locations. Learning to tell the difference among different forms of nomadic, multi-layered or diasporic subjectivity is therefore an important methodological but also ethical issue.

In order to change power relations, the nomadic subjects aim to account for their embodied and embedded location in space and time. This is the only way to map the power differences that define these respective and diverging positions. Only then can they provide alternative and creative forms of resistance to and re-configuration of these different ways of becoming nomadic, respecting the different locations they inhabit. This means that bodies and material locations are interlocked: bodily materiality works in tandem with the social embedded-ness of subjects.

I share with this exhibition a sustained focus on the ‘disposable’ bodies of women, LBGTQ+, youth, and others who are sexualized, racialized, naturalized. They are marked off negatively by age, gender, class and income. Ultimately, they are disqualified from humanity. The question is how these embodied and embedded subjects came to be inscribed with particular violence in regimes of power that led to dispossession, disqualification and marginalization. The crucial thing here is not to have these differences turn into sources of division, antagonism and fragmentation.

On the contrary, the positive force of difference shows to be one of the strengths of this exhibition. The photos set side by side the political genealogies of the women’s and the LBGTQ+ movements, and especially the trans movement—letting them tell their respective tales. These tales resonate and echo, but also contradict and question each other. They charge the viewers with the responsibility to sort out their own multiple and potentially contradictory responses, reminiscences and aspirations. Differences are processes of constant becoming. Becoming is not a one-way road but a multi-directional set of paths. The work of difference is never done.

Against Eurocentrism

Nomadism is necessarily a critique of stable and fixed identities and therefore also of Eurocentric essentialism. The nomadic subject stands against any idea of neo-colonial, nationalistic and white-supremacist identity formations. The emphasis on nomadism is intended as a serious warning to people who consider themselves as “the centre”. And while there are many centers that structure the contemporary world, the margins are always more numerous and more crowded. The insight of nomadic subjectivity is that heterogeneity, radical otherness and hybridity constitute the origin of all identities. In so doing nomadic subjectivity pursues a double aim: to critique the despotism of fixed and stable identity as formations of dominant power, and also to open spaces of resistance.

My nomadic project is a critique of Eurocentrism from within and a way of activating the centre away from inertia and self-replication. A great deal of my work is motivated by the necessity to give a critical and progressive task to people who are situated at the centre—in one of the many centers of the global economy. In a globalized world, margins and centre shift and destabilize each other in parallel, albeit dissymmetrical, movements. I firmly believe that, unless the centers can get activated in non-fascist, anti-racist and anti-sexist directions, nativist populism, patriarchal violence and racism cannot be stopped. The critique of Eurocentrism from within Europe, for instance, questions the cultural mind-set based on universalism as a dis-embedded and dis-embodied subject position. A European nomadic subject, willing to move across anti-racist lines, rejecting the privilege of whiteness and producing a critique of methodological nationalism, is capable of joining a planetary debate which black, anti-racists, post-colonial and other critical thinkers have put on the map.

In-between

I have been insisting on the intersection of space and time, locations and memories, in the nomadic methodology of accountability for one’s embodied and embedded subjectivity. Such relational and collective activities activate the process of putting into words and images that which by definition escapes self-understanding. A “location” is not a self-appointed and self-designed subject-position, but rather a collectively shared and constructed spatial-temporal territory. A great deal of our locations escape self-scrutiny because they are so familiar that one does not even see it. Becoming aware of one’s location refers to a process of consciousness-raising that requires a relational bond to others. This relational openness is the defining trait of nomadic subjects. In this regard, photography is a particularly well-suited medium to capture the processes of becoming-nomadic.

Photography is relational and it thus mirrors how the process of subject-formation works, namely by mutual readjustments and reciprocal questioning. We all become subjects by negotiating between external social forces, collective and codified by political structures, and inner drives that, while being just as relational, also mobilize the self’s highly personal and singular forces. As I wrote above, nomadic subjects are not One and the Same: “we” differ. And we differ not only along longitudinal and latitudinal variables, that is to say from each other and among ourselves, but ‘we’ also differ within. We differ from ourselves, in an internal motion of nomadic dis-identification from any stable or fixed identity. In other words, we are—each of us is—heterogeneous assemblages.

This relational approach of the nomadic subject requires that we think of power relations simultaneously as the most “external”, collective, social phenomenon and also as the most intimate or “internal” one. Or rather, power is the process that flows incessantly in-between the inner and the outer. Power is a strategic situation, a position, not an object or an essence. Subjectivity is the effect of the constant flows of in-between inter-connections. As sites of multiple, complex, and potentially contradictory sets of experiences, defined by overlapping intersectional variables, such as class, race, age, life-style, sexual preference and others, nomadic subjects occupy a flowing and multi-directional position.

For nomadic subjects, the personal is the political—to quote the famous feminist slogan. The personal and political are both collective entities, made of constant shifts and negotiations between different levels of power and desire. All subjects are caught between entrapment (the negative expression of power: potestas) and empowerment (the positive expression of power: potentia). Whatever semblance of unity there may be is the dramatization of a multi-layered relational entity within a relational exchange. Here, the photos of Marialba Russo come to mind, as a perfect expression of the dynamic relation that self-images entertain with both individual and collective identities. These images unfold beyond the binary scheme of gender opposition masculine/feminine.

The process of becoming a nomadic subject is embracing the deep complications of conjoining the personal and the political. In the end, what matters is the founding, primary, vital, and original desire to go on becoming. But one always becomes in-between.

In-between is a transversal force. Transversality is crucial in that it cuts across all categorical divides, in contrast to the binary, oppositional ways of thinking. Nomadic bodies are diversified, transversal assemblies. They act as thresholds of transformation, surfaces of intensities and interaction with multiple others. Transversality demands a radical recombination of self and other, a deep relationality that acknowledges interdependence and mutual specification. In this respect, the core of the project of nomadism deals with trans-subjective relational processes and transformative politics. This is why I was so struck and also moved by the convergences across the multiple faces and places covered in this exhibition. Across their multiple differences, they compose a plane of relational encounters and resonance. In-between becoming is a never-ending process of establishing connections.

Affirmation

Back to some of the photos: faces smile, mouths burst into laughter, and eyes twinkle with joy. Even through the tears or a grimace of pain, these faces assert and affirm. Let me reassert by way of conclusion the point I made at the beginning, namely that these photos of nomadic subjects are affirmative and joyful, even when they display the pain and hardship of their embodied differences. The ethics of affirmation are central to the process of becoming nomadic. This means the effort to increase our respective relational capacities and reach across multiple others, taking them in, so to speak. Opening up to diversity and heterogeneity.

The project of nomadic subjectivity stresses the affirmative force of a political imagination that is not tied to the present in an oppositional mode of negation. It rather actively strives to create collectively empowering alternatives. This mobilizes the resources of the imagination. The imagination is not utopian, but rather transformative and inspirational. It expresses an active commitment to the construction of social horizons of hope. Hope is a vote of confidence in the future, not a utopian drive, but a very situated practice.

To activate affirmative practices, it is important to enter into dialogues and relations with subjects, activities and discourses taking place outside the academic world, in a myriad of venues within the knowledge economy. Therefore it is crucial to include the arts, music, architecture, cinema and the media. That is why this exhibition on photographs by women is so timely. Museums and art centers are major players in this quest for transversal ways of producing knowledge. This photo exhibition is both original in content and orientation, but it is also emblematic of the kind of research practice that contemporary art is capable of enacting.

The task of thinking nomadically today is not contained within institutional practices, but is an on-going practice that emerges from an honest and at times cruel confrontation with the world we now inhabit. This means that it is important to establish relational dialogues with political practices and movements like feminism, environmentalism, anti-racism and alternative globalization movements. The nomadic subject is my chosen figuration to produce an affirmative reading of the present, in terms of cultural, political, epistemological and ethical concerns. It is my way of expressing an insatiable and loving curiosity for the world, in all its contradictions. Just look at the laughing, crying, inquisitive faces of Soggetto nomade exhibition: they also express an irrepressible love for the world.