Empathic Loops and Open Poetics

What happens when we think of the space of art as a living body?

Abbas Zahedi became an artist by way of a medical education, a philosophy symposium in a chip shop, community organising, and “Dissociative Realism”, as described in an essay by Arsalan Isa. With Eva Wilson, Zahedi explores translation and transplantation as frameworks that allow us to understand ourselves in relation to others — as life-support systems to counter the erosion of identity through trauma.

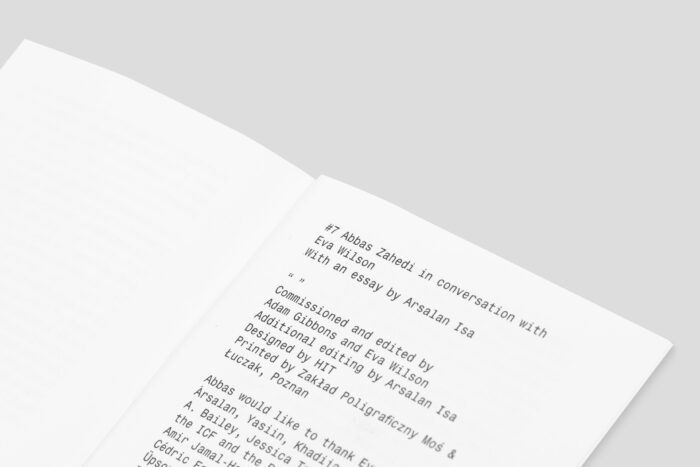

Here is an excerpt from the book part of the series edited by Adam Gibbons and Eva Wilson, “ ” (quotation mark quotation mark).

Eva Wilson: How does ‘meaning’ come about? That’s such a big question. Like you say, meaning is fragile. Something that has meaning can be held over time, between people. Some ideas or objects seem to be meaningful for many people over a long period. How can an object, or a constellation, or an installation be or become meaningful? Can meaning potentially be embodied in material, or material change? Something experienced as genuinely meaningful can emerge from a situation or a framework that specifically supports different, or conflicting interpretations, that doesn’t rely on stable references or monisms. Maybe this potential for multivalence is even a defining factor. I think I’m imagining this process as a form of non-combative dialectics, where the contemplation of one thing kindles another or sets it in motion. A back-and-forth or a kind of resonant oscillation, like Alvin Lucier’s sound piece I am sitting in a room [1969]. The best description of that performance is the constituent language of the work itself, the statement spoken by Lucier: ‘I am sitting in a room different from the one you are in now. I am recording the sound of my speaking voice and I am going to play it back into the room again and again until the resonant frequencies of the room reinforce themselves so that any semblance of my speech, with perhaps the exception of rhythm, is destroyed. What you will hear, then, are the natural resonant frequencies of the room articulated by speech. I regard this activity not so much as a demonstration of a physical fact, but more as a way to smooth out any irregularities my speech might have.’ By the end of the performance, the words — even though they are embedded — become unintelligible, and the room itself begins to ‘speak’. Anna L. Tsing describes something similar using the term ‘contamination’ — meaning an encounter that is involuntarily transformative [The Mushroom at the End of the World, 2015].

Abbas Zahedi: In terms of materiality, the question of meaning makes me think of the associations that are formed over the course of our lives with different objects, bits of matter and information, including the relationship to our own flesh and imagination. Meaning, in this sense, exists for me in the shifts, clashes, and transitions that are evident in an artwork, whether it’s to do with mixing codes associated with a material, or repositioning objects, so as to shift how we perceive them on an affective level. I think when this is done well, it can have the effect of even showing how meaning is produced. In my case, I tend to work collaboratively in order to emphasise the relational dimension, considering ways to involve others, together with spaces, histories, ideas, and materiality, in ways that feel sensitive to the context at hand. To help navigate this constellation, I often imagine myself as the guest I wish to host via the work, and make myself vulnerable to a working process that is held in relation to the making; establishing a space where I can feel, think, fail, and enact experiments.

I try to relay these complexities in a manner that remains open to feedback and change, acknowledging the collective within the personal and vice versa. I think of this as an empathic loop that gestures towards a cross-cultural open poetics. It can be a way of holding space together, to honour each person’s need for collective strength, which also provides the support, care, and nurturing we require for our own individual journeys.

This requires balance in the formal aspects of the work. For example, if I were to combine personal narrative with a lot of figuration or representational elements, I feel like it would collapse the point of entry for others; they wouldn’t be able to sustain their own emotionality in the space. Work like this often verges on being didactic, or informative in a prosaic way — like telling you what to feel, or chronicling what’s already happened, as opposed to opening up space for what’s taking place in the encounter itself. I don’t know why it makes me think of propaganda, or, again, a prophetic model, in which the artist takes on the role of the visionary recruiter of a cause or vital insight, often based around their own subjectivity, or the subjective representation of some othered position.

The skill of turning all this into an artwork, if there is one, and if that’s the skill that I try to employ, is communicating something that when it’s experienced, is not at the forefront of what’s taking place. There is a kind of ambiguity and distance, allowing people to inhabit the work on their own terms. Oftentimes, I use things that are easily recognisable, objects that people have their own associations with. The way the space is set up is minimal. It gives people a chance to inhabit it in different ways, they can move around. That is where the sense of generosity or hosting comes into play; putting less in the space as opposed to making it immersed with objects or imagery. I feel this sets a dynamic in which the audience may be able to become more self-aware, potentially of their own needs, in terms of what they expect to see, and what role they inhabit when they are in that space. Rather than illustrate this dynamic, I try to think of ways that this sense of interdependence can come through and be felt at some level.

Wilson: I think one of the difficulties of working within the model of prophetic art as you describe it is that the issues that are addressed are often on the scale of hyperobjects: too big and distributed to really compute or relate to intellectually or emotionally. Practices that address these issues, such as climate change, are confronted with the task of scaling them ‘down’ to a format that offers an individual entrypoint. The risk for the artwork lies in resorting to didactical approaches; and in terms of the cause, this approach can lead to an emotional form of engagement by way of consternation, sadness, or shock, a rush of affect after which the viewer is sent on their way with the perception of having confronted or endured a matter of remote concern temporarily, paradoxically absolved from taking further action. I guess this revolves around the question of how we assume responsibility or accountability in relation to our surroundings, and whether art can or should function as a conduit in the search for an answer.

I am torn about this, because I do see the risk of self-indulgence in art, and, on the other hand, especially in relation to climate action, I’d be inclined to say that many different approaches are needed. Earlier, you pointed out art’s potential to allow the viewer to feel and sit with their anxieties. This seems to me to suggest neither cathartic acquittal, nor righteous indoctrination, but instead a mode of remaining in a space of empathic self-awareness and awareness of the world we are part of. In this sense, creating structures that counteract exploitation and extraction might feed back into a relationship with ecology, even if they don’t address it at first glance.

There is substance in generating space rather than making an object. On any other day, we’d hear and feel the rumble of the underground every few minutes here in this room. The train tracks for the Circle Line run right behind the house. But today, because of the rail workers’ strike, it’s quiet. The silence indicates a collective refusal of labour in support of fairer living conditions. But on the recording that we are making right now, we will have a trace in the form of an absence of sound, which we can nonetheless draw attention to. You and I have talked before about the word lacuna, the term for a gap, or for a word that doesn’t but should or could exist, a pointer to something that isn’t there.

In your show Metatopia 10013 at anonymous gallery in New York, there are two literal pointers, arrows indicating two geographical locations. One of them points towards the Twin Parks apartment block in the Bronx, where seventeen people died in a fire in January this year, and the other to Grenfell Tower in London, where a fire, which started in a faulty fridge and spread due to substandard external cladding, killed seventy-two people in 2017. The arrows, or qiblas, cut from domestic floor mats, point to places which physically exist in the world, but they also point to an absence or to a great loss.

Inversely, you draw something out of or charge the supposedly empty space of the gallery by distilling the humidity out of the air in the room. This makes a substance apparent that’s there anyway but not felt, seen, or consciously experienced. The humidity from the air is collected in a dehumidifier and then fed into a receptor, Waterphone 10013, an instrument that you designed together with the composer Saul Eisenberg. You, or whoever plays the instrument, then make this distillation resonate into sound. By allowing the humidity of the space, which is produced by bodies, breath, a shared ecosystem or microclimate, to resonate in a physical sense as it becomes sound, you let these resonances re-enter the bodies of those in the space. The sound, the music that the instrument emits, the oscillations that set eardrums and membranes into motion, become something that as a visitor you can share, or rather that you can’t not share in.

Zahedi: Yes, and if visitors cry, that’s the same moisture that they’ve taken in, and then those tears feed back into the atmosphere of the room.

My scientific background as a medic means I think in terms of systems, how changing one thing in the body affects all kinds of other things. It makes me understand matters in terms of balance in a very relational way. Each work, or each space that is created, is a testament to the relations that surround it. I try to guide the works and charge them towards a certain energy, but I accept that I’m not always in control.

With a show like Metatopia 10013, the gallery served as a point of departure to organise a set of references and connections, a node in a network of grief, so to speak. It conflates some of the ideas that came before in my work. There are dripping things, there are pointing things. It’s Ouranophobia SW3 and How to Make a How From a Why? compacted and meshed together. One part of a work may end up in another work based around a different line or body of practice. All these different ways of presenting, whether it’s performance, a white cube setting, a site-specific approach — or site-sensitive, as Tony Cokes puts it — mean that one system may be developed in a particular space, and then be reconstituted in another. It’s not archival in that sense, but a latent dynamic waiting to be re-realised. Astrida Neimanis and their concept of hydrofeminism helped me perceive this at a fundamental level, by showing that we are all interconnected through watery entanglements and circulations [‘Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water’, in Undutiful Daughters, 2012]. Metatopia 10013 was really a testament to their work, and I continue to use different kinds of liquid as material in my practice, especially when it comes to the interconnectedness of grief caused by systemic injustices — we all suffer, not just the ‘impoverished’.

These were my thoughts when making the show at anonymous in New York. Joseph Ian Henrikson, who runs the gallery, and I were speaking about my previous shows and how we could imagine something for his space by thinking of them as systems and conflations. In the middle of this process there was the fire in the Twin Parks projects in the Bronx. The demographic of people who died in the fire was very similar to that of Grenfell and the wider social housing surrounding it, which is where I was raised and still live to this day. Over the years there’s been an increasing sense that the local authorities and other influential parties just want us to disappear, or at the very least be invisible. We are seen as pests and the approach is like pest control.

I’m very aware of what it feels like to be in that situation. The conflation of those two places created new space in an emotional way for me. Neimanis’ hydrofeminism helped me to envision this through the water cycle of the gallery, how I could collect its humidity, a mixture of atmospheric vapour which is exhaled from bodies in the space. The drops were then fed into the waterphone instrument. A third liquid was also added: rosewater that was brewed on the gallery floor in a transparent vacuum- sealed bag. The gallery staff were very hands-on in this process, as I had asked them to discard the spent roses somewhere public, so as to create a ritual and system of grief for the show.

The two pointers on the floor came out of the idea of the qibla, which is an Islamic motif that points in the direction of Mecca. That’s the direction that people are called to pray five times a day, following the passage of the sun. So for me, they’re not objects that you look at, they are calls to action. Usually you only have one qibla, because there’s only one Mecca, and everyone has to go there. In this case, by making two, I raised the question: could such a qibla be applied to other spaces? And is there another kind of prayer or some call to action that is social or otherwise? Something that gives access and not just visibility; to go beyond the idea of a totem? Like trying to reroute the teleology of an art gallery towards another cosmic system. Is it possible to shift the register of a framework that was intended to subjugate anyone who adheres to its specified code? For example, if you speak to police, your speech is only understood through the prism of law, there is no other option. The act of speaking to them includes an acknowledgement of their terms of engagement, that’s how the legal system is set up. And in art it’s a similar premise: if you show in an art space, you are set up to be absorbed by its code.

From a Muslim point of view, there is the idea that when you face Mecca and pray, you will not know if your act of worship has been accepted until judgement day. This uncertainty always struck me, and I wondered about its function, as a form of lexical entrainment whereby you have to accept these terms to prove your sense of devotion, in parallel with the fact that prayer is also a public act, a show of allegiance, and adherence to a code that is accepted by your peers. The status of anyone’s prayers cannot be questioned by another, so you have to assume the sincerity of your fellow counterpart, whilst at the same time doubting your own. An artwork can have a similar function, like how going to a gallery always makes you feel like you’re unsure whether you understand the work and are able to identify yourself as sufficiently ‘enlightened’ to receive its premise. The fact that I am considered an artist now, presenting and performing work, doing the deeds of art, means my status is confirmed externally. And yet, on an internal level, there is a sense that this is not enough; I need to do more to maintain this position that I’ve achieved through the gaze of others.