Dreamers of the Day

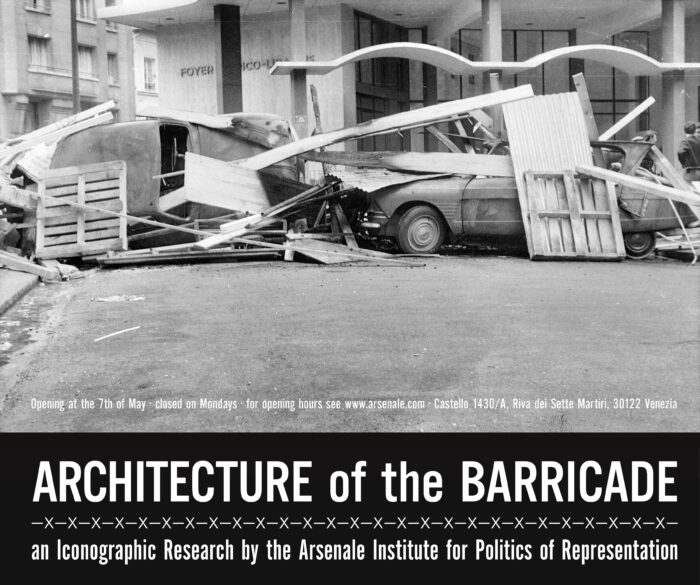

An attempt to imagine the Venice Biennale as a shared rooted cultural space

As in the piece that I wrote last year The Responsibility of a Cultural Institution, this text aims as well to provide tools to push forward the deconstruction of the “Biennale di Venezia” towards a shift from the inherited institutional structure “that reinforce dominant narratives,” rejecting the “notion of a neutral and authoritative institution” in order to imagine a new model for a shared cultural space. Imagination is productive only if it is rooted in reality, and awareness is essential to be as realistic as possible in order to “demand the impossible… to make what is currently considered possible, impossible.” [1] Knowing the history of a cultural institution like the “Biennale di Venezia” means knowing that some utopias that have been realized thanks to the imagination of the people who represented it in the past, were possible thanks to the political will of the public administration. [*]

In this text I address the issue of the privatization of public space which in Venice is more evident and violent than in any other place—it has a specific universal potential that makes it unique and significant. Taking as an example the public asset of the area of the public gardens of Castello “in use at the Biennale,” which is managed as if it were private, I try to highlight the responsibility of the public administration and the opaque relationship between the local and state management of a city through the use of a cultural institution, the Biennale, private law entity under public control, in fact defined as being of “preeminent national interest.” It is a text I have been working on for a long time because I wanted it to be concise and clear to become a useful tool, but the initial reasoning that led to the issue of the management of the Venice pavilion, a public space owned by the city, deflagrated with the news of the concession given by the mayor of Venice to Qatar to build a pavilion in the gardens, a protected public good.

We need all our imagination to really begin to transform what is now considered possible, impossible.

I.

Social reality is structured through laws that regulate relationships and protect the rights of objects and subjects. When we talk about institutions, it is necessary to know their legislative history that guarantees a framework of awareness within which we can move. This chapter is a tool that allows a summary of the history of the constraints on the area of the public gardens of Castello “in use at the Biennale.” This is a quite dry reading, but a necessary framework.

The public gardens of Castello “constitute today the most significant addition of public greenery to the landscape of the San Marco Basin, and are one of the most important and interesting urban planning interventions carried out in the fabric of the lagoon city in the 19th century.” [2] The first restriction on the area dates back to the “Bottai law” 1497/1939, the first organic national law on the protection of natural beauty in Italy. [3] The entire area of the gardens was then subjected to a panoramic constraint pursuant to the same law based on the ministerial decree for architectural and environmental heritage (1 August 1985) which declares the “Venetian lagoon ecosystem to be of considerable public interest.” [4] This decree is part of the so-called “Galasso law”, a law of the Italian Republic that is a pillar of landscape protection, because it introduced the constraint that aims to preserve Italian territory’s environmental and cultural heritage, protecting areas of significant public interest. [5] This was the first organic provision of the Italian Republic in the field of land management and it established that “the protection action within the areas identified according to the directives of the legislature does not totally exclude building activity, but submits it to the approval of the bodies responsible for protection (Superintendencies), as well as to the Ministry of Cultural and Environmental Heritage.” This means that specific authorization becomes necessary for any building intervention, even if small. Furthermore, “the regions are obliged to draw up landscape or urban territorial plans that protect the territory and its beauties, and can establish total non-buildability.” The areas identified by the Galasso law are “subject to state jurisdiction”, that is a landscape constraint which establishes that these areas are part of the State’s heritage which regulates their management and use.

The Galasso law also affirms the “rights of civic use,” that is, the right of the inhabitants of a community to use free of charge assets protected by the State, such as public gardens that present elements of significant natural or historical beauty. This means that any intervention that could alter their physiognomy or their aesthetic appearance must be subject to specific authorization, with the aim of preserving the landscape value of these areas. [6]

Decree prot. no. 20869, notified to the Municipality of Venice on 25.11.1998, also subjected to specific constraints “the Gardens in use at the Biennale and some exhibition pavilions pursuant to and for the purposes of law 1089/1939 on the protection of things of historical-artistic interest.” [7] The area was further subjected to the protection provisions with Legislative Decree no. 42/2004 of the Cultural Heritage Code pursuant to art. 10, Part Two, as it is of historical interest and owned by a public body: the Municipality of Venice.

“The original function of the Castello gardens (…) has been modified with the establishment of the cultural activities of the ‘Biennale’ which [has] removed a large part of the surface from public use, causing some contradictions on the real use of the area.” The “Detailed Plan ‘Biennale Gardens,’” published in 2001 by the Municipality of Venice, claimed that it was “necessary to reconsider the multiple needs of the ‘Biennale’ within the context of a new management and reorganization of public gardens,” calling into question “the compatibility between the recreational and leisure function of public greenery with the cultural activities of the ‘Biennale’ [due to] the private use of part of the area of the latter.”

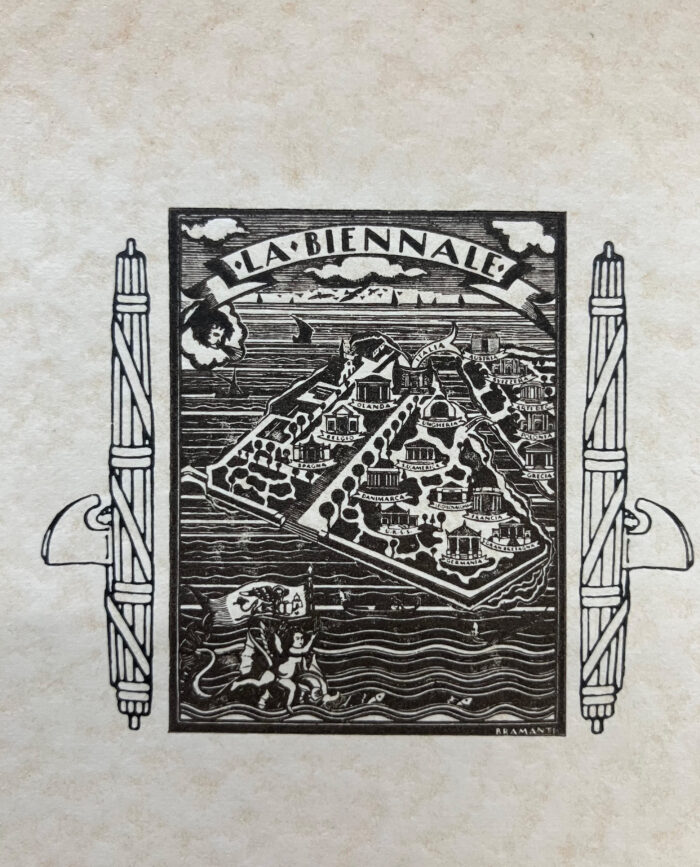

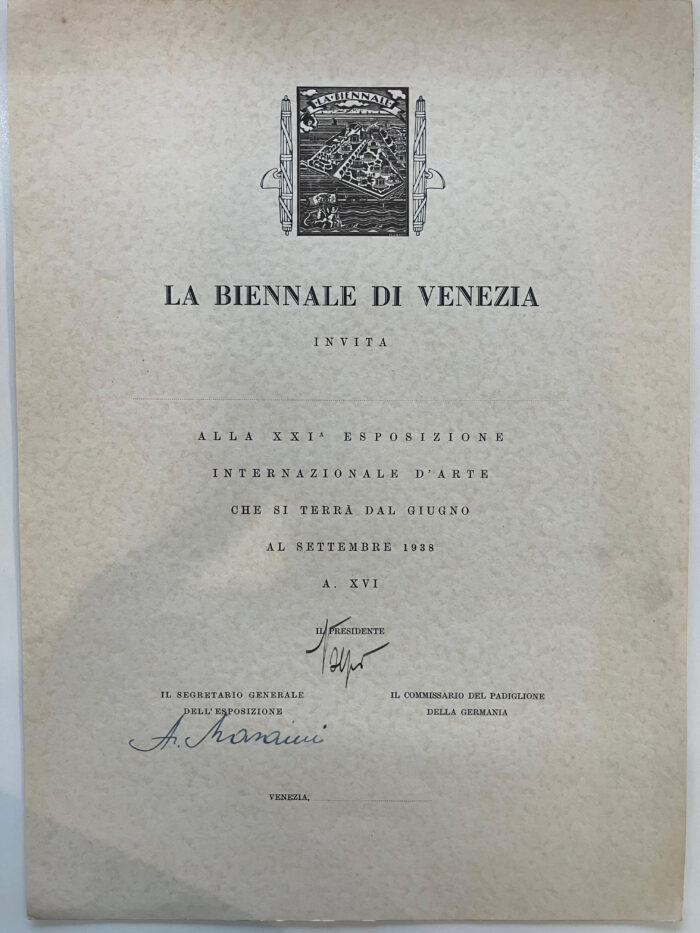

The disconnection between the area of the gardens “in use at the Biennale” [8] and their public function, occurred in 1938 when the royal decree-law of 21 July 1938-XVI, n. 1517, establishing “an autonomous body called The Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition,” nationalized the International Art Exhibition of the city of Venice. It is from that moment that the concession of the area of the public gardens “in use at the Biennale” changes nature because it is no longer managed by the Municipality of Venice internally, but becomes a management relationship of a territory between the city and the Italian State; the reform in fact provided the headquarters to be maintained in Venice and the mayor to be designated as vice president. The official image that began to appear on institutional letterheads at that time, depicted the gardens as if they were cut out following the perimeter of the fences, which became an island floating in open waters. The island seems to come out of a weird dream: it is a neat and verdant garden dotted with pavilions with eccentric architecture, each one with a cartouche indicating its ownership. At the bottom left of the image, it is barely perceptible a very small white bridge leading out of the illustration as if the fact that the garden was connected to the city, interrupted the dream.

The deracinating of that area of the gardens from the city that for forty-three years had been the ground in which the Exhibition had taken root, was wanted by the state public administration. This alienation of a public space of the city, was possible thanks to the connivance of the Venetian mayors who succeeded one another from 1926 to 1943—who were all members of the PNF (National Fascist Party)—with the president of the “Venice Biennale” who by law had to be “a person of clear fame, resident in Venice, designated by the Presidency of the Council of Ministers.” From 1930 to 1943 the appointed president was Giuseppe Volpi, a Venetian entrepreneur, fascist plenipotentiary minister, Governor of Italian Tripolitania, Minister of Finance, first attorney of San Marco, president of Confindustria, the one who inaugurated the extractive model of Venice understood as a resource and of the Biennale as a source of income for business interests and a useful resource in international diplomatic agreements. The separation of the area “in use at the Biennale“ from Venice, allowed the abstraction of that space from its context making its use permissible as a simple backdrop, thus inaugurating the most replicated exhibition model of the contemporary era: the biennials as a “global white cube.”

This relationship with the city has become even more complicated with the 2004 decree law that transformed “a public administration into an entrepreneurial entity, to be managed from the perspective of public bodies (…) which [puts] it in a position to be governed like a business and therefore to better seek its own revenue, remaining public and autonomous.” This change in the legal nature of the institution has made the relationship between public and private interests more opaque. When in 2001 the Municipality of Venice published the “Detailed Plan ‘Biennale Gardens’” requesting “the restitution of the historic garden of Castello to public use, compatible with the exhibition and museum needs of the Biennale,” the mayors of Venice did not react until 2014, allowing the Biennale to extend the period of “exhibition needs” over the years. After that, the empire of the mayor in office today who allowed the privatization of the public space of the gardens to take place began.

II.

I would never have imagined that I would have the opportunity to follow all the phases of the installation of a new national pavilion in the area of the public gardens “in use at the Biennale.” My first research work on the institution was in 2005 and concerned the historical reconstruction of the political and economic motivations that had led some nations to obtain the concession of a terrain to build a pavilion within that area, and of those that had never obtained it despite some having been on the waiting list for decades. [9]

At the time, the most recent pavilion inside the Biennale gardens area was South Korea, which dated back to 1995, and it was already incredible that it had obtained permission to build because, according to the Galasso law, the area was no longer buildable already in 1988 when the permission was granted to Australia. [10] It seemed incredible, especially after the 1993 edition and in a moment of change in global structures after the fall of the Berlin Wall, that the institution had not taken the opportunity to “formulate a proposal… to claim a different cultural project… a mosaic structure [because] is no longer possible the recognition of the purity of the national core, but rather the positive contribution of a trans-nationality, intertwining of peoples… overcoming the autarchy [of] the National Pavilions.” In 1999, however, the institution decided that a section of the new venue of the Arsenale be granted to the nations that had requested a pavilion, granting the possibility of having an exhibition space in the new official venue, inaugurating a trend that seemed out of date and limited inside the fences of the nineteenth-century charm of the Biennale garden.

In 2024, however, the Municipality of Venice granted a plot of terrain inside the fences of the Biennale area to the State of Qatar. The area of the garden “in use at the Biennale” is public and, according to the Galasso law, the whole garden area is environmental heritage and therefore the rights of “civic use” apply, furthermore the Biennale is recognized by the State as “of pre-eminent national interest,” a cultural heritage. It is therefore doubly a common. The Municipality of Venice and the institution that hosts it on its ground, allow an improper use of a space that is public. With the concession given to Qatar within that museum that is the Biennale garden, all these elements short-circuit.

I think it is useful to propose a consideration that has to do with the concept of “good administration,” a principle established by art. 97 of the Italian Constitution, later expanded and specified by art. 78 of the Consolidated Law on the Organization of Local Authorities (TUOEL). This principle establishes that the public administration must ensure “the good functioning and impartialit,” which must be translated into efficiency and transparency and respect for the rights of citizens and that the public administration must ensure the good functioning of services such as the right of access to administrative documents (law 241/90), which allows citizens to know the activities of the administration and to “watch over” its work. In short, it is established that the relationship between the public administration and the citizens must be based on “collaboration” and “good faith” and must act in full compliance with the laws and regulations in force.

In the meantime, in 2020, the Fondazione La Biennale di Venezia has equipped itself with a Code of Ethics “in order to clearly and transparently define the set of values that inspire it (…) a set of principles and guidelines that are designed to inspire the activities of the Foundation and guide the behavior (…) of all those with whom the Foundation comes into contact (…) with the aim of ensuring that efficiency and reliability are also accompanied by ethical conduct in business relationships.”

On July 24, 2024, a press release published on the official website, the Municipality of Venice begins with a long panegyric in which it reminds its citizens that the immense fortune of having a unique historical and artistic heritage entails burdens and therefore informs that it has accepted the donation of fifty million euros to satisfy unspecified “pressing needs of the city.” The mayor himself ends up declaring that the city is “at the disposal of the entire Italian country system” because “it has always been open to the world, as a place where different cultures and peoples meet and grow.” For this reason, that is, for the good of the city, the mayor announces that he has accepted Qatar’s proposal “to create a new national pavilion in the Napoleonic gardens of Castello (the Gardens).” This press release followed the one published on June 7 of the same year, in which the Municipality informed citizens of the signing of a Cooperation Protocol with Qatar Museums to “strengthen existing relations in order to improve collaboration in the cultural and socio-economic fields.” He enthusiastically reports that “the agreement coincides with Qatar Airways’ announcement that it will resume direct flights between Doha and Venice.” On July 24, the Municipality reiterated that the Cooperation Protocol signed in June with Qatar Museums had been “announced on the day Qatar Airways resumed direct service between Doha, the international hub for Asia, Africa and Oceania, and Venice Marco Polo Airport.” It is known that Qatar aims to widely expand its national airline’s access to the international air market and that this is “the main issue on which the emirate’s illegal lobbying has focused.”

It is not shocking that the Qatar pavilion at the Biennale is a clause in an economic agreement with the city of Venice because it has always been like this: since the institution was nationalized, nations have always obtained pavilions for national diplomatic or economic interests. It is shocking that the local public administration, with the connivance of the national one, can continue to use the institution of “preeminent national interest” exclusively economical and never cultural, as in the darkest moments of its history. Qatar’s admittance into a public space, protected and bound by state and local laws, only makes the turbidity of the selection procedures for granting pavilions to nations macroscopic and manifest, casting serious doubts on the “clarity and transparency” and “reliability” of the “ethical conduct in the context of negotiating relations” of the institution and on the “good faith” of the local public administration.

It was just over a year and a half ago that ANGA was formed to contest Israel’s presence at the Venice Biennale. For ANGA it was “the official presence of Israel at the Biennale” that disqualified “any discussion on equality, justice and freedom, in art as in life” and considered the silence of “all those who participate” unacceptable, calling them “accomplices of art washing.” The Italian Minister of Culture at the time responded indignantly by calling the request of more than 19,000 cultural workers from all over the world “unacceptable” and “arrogant”, closing the speech with the declaration “the Venice Art Biennale will always be a space of freedom, of meeting and dialogue and not a space of censorship and intolerance. Culture is a bridge between people and nations, not a wall of division.” The Biennale instead declares that “all the countries recognized by the Italian Republic can in total autonomy request to participate officially. The Biennale, consequently, cannot take into consideration any petition or request to exclude the presence of Israel or Iran from the next 60th International Art Exhibition.” The Biennale is an institution that does not take a position, but in order to be consistent a contemporary cultural institution has the duty today more than ever to take a position and do not be a “neutral, authoritative institution,” especially one with a history that remains obscure and never addressed. ANGA’s complaint had an impact on Israel’s participation in the 2024 art edition and the 2025 architecture edition. The institution acts with the authority of an absolute state in the space of culture, regardless of the evidence that democratic protest is an effective tool especially in that space which is of resistance, as cultural spaces are. Since the Biennale gardens are also a public space of a city, good governance would include the protection of dissent. [11]

The Biennale claims to aim to “guide the behavior (…) of all those with whom (…) it comes into contact” with the “principles and guidelines” that inspire its activities. If we consider with which nations Biennale stipulates concession contracts, especially in the spaces of the official institutional venue of the Arsenale, the rule according to which all “countries recognized as independent states by the Italian government” can apply for a national pavilion also falters. This is because there is another principle to take into consideration, namely the Treaty on European Union which places respect for human rights at its centre, both within its own borders and in relations with third countries.

Qatar is more striking than the others, because by entering a regulated and protected place, it has broken through the boundaries of the possible. Amnesty International’s 2024 report documents that the right to freedom of expression is restricted in Qatar: women are subjected to a guardianship system where they need permission from a male guardian to study, work, travel and receive no protection against domestic violence; LGBTQ+ people face arbitrary detention as do those speaking out for greater rights and freedoms because of their sexual orientation or gender expression; migrant workers continue to face human rights violations. In 2023, documents from Qatari finance ministers were made public on tens of millions of dollars in illicit funding received directly by Benjamin Netanyahu for his election campaigns in previous years. More recently we have seen how Qatar intends to influence international events in its favor with its immense wealth, giving absurd gifts and financing “all those who accept its money.” One of Qatar’s strategies is to increase soft power through sports and culture. Qatar Museums—the entity that will manage the national pavilion at the Biennale gardens—is a government body founded in 2005, a key player in the implementation of Qatar’s cultural policies.

In this scenario, according to the Galasso law, the mayor of Venice has the power to decide on building permits on restricted municipal lands, submitting them “to the approval of the bodies responsible for protection (Superintendencies), as well as to the Ministry of Cultural and Environmental Heritage.” Since the institution is a body controlled by the ministry itself, there does not appear to be any impediment that could hinder obtaining the exception of protection constraints. It is the mayor himself who declares that Venice is “at the disposal of the entire Italian country system.” Luigi Brugnaro, the mayor of Venice since 2015, the one who granted Qatar a portion of terrain which is protected by the superintendency and belong to the city, is a Venetian entrepreneur who, according to his own auto-fiction, resigned from all his positions when he was elected, entrusting his company Gruppo Umana—an employment agency with a turnover of almost 1 billion euros—to a blind trust. On May 12, the Venice Public Prosecutor’s Office submitted to the GIP (Preliminary investigations judge), the request for a referral to trial for the corruption investigation called “Palude” (swamp) which has to do with the purchase in 2006 for 5 million euros by the entrepreneur-Brugnaro of an area of (polluted) land overlooking the lagoon, revalued in 2020 for 85 million euros. In 2024, this area entered the Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan of the City of Venice, which includes the construction of a new terminal connecting Venice to the mainland. “So Mayor Brugnaro could expropriate from the citizen Brugnaro, an asset that guarantees a large capital gain.” In addition to the investigation for which he was sent to trial, doubts remain about the continuous conflicts of interest between the public office and the private interests of the mayor that undermine the transparency and good faith that are duties of the public administration.

III.

Finally let’s try to build a possible reality always through real facts and let’s dive into history for a moment. During the first National Celebration for the Unification of Italy on September 20, 1895 in Venice, part of the demonstration headed in front of the monument to Paolo Sarpi and then under the house of Riccardo Selvatico. The chronicles report that it enthusiastically intoned the chorus: “Long live September 20th! Long live Selvatico! Long live Paolo Sarpi!” [12] Riccardo Selvatico had been the mayor of Venice for five years and had resigned on July 28. His radical and progressive administration would leave a lasting mark not only for the events and enterprises carried out, but also for a “collective imagination [of] a new and possible vision of the world.” The Selvatico administration wanted to accredit itself as the administration that, first of all, acted in a manner consistent with the paradigms of a country born from the Risorgimento, placing civil and economic progress at the forefront, as new paradigms of public utility.

Supported by a base of democratic and conservative alliances that shared a secular approach, Selvatico was able to launch an advanced reform program that aimed to broaden the social base of Venetian democracy by municipalizing public services. As mayor, he promoted the creation of professional schools, the reorganization of the health service and charitable institutions, the foundation and funding of the Chamber of Labor, [13] the construction of public housing and the redevelopment of the city, the reduction of the tax burden, the return of the public school to its offices of national civil and secular education. He curbed the abuse of public offices by supporting redistribution, convinced that historical necessity required public offices to no longer be able to remain “contemplative and inert spectators” and “defenders of an economic liberalism and individualism that allowed private speculation to exploit the common good.”

It was the Selvatico administration that decided to build the monument to Paolo Sarpi and to inaugurate it on 20 September 1892, the anniversary of the “Presa di Roma,” giving it a clear political and ideological meaning. Like Giordano Bruno, Sarpi was a symbol of the liberalism of the Risorgimento in post-unification Italy in search of an identity, one of the protagonists of the highest philosophical conquests of humanity that could finally be celebrated thanks to the “concept of the secular independence of the state that dominates modern legislation.” Paolo Sarpi, the “secular lawyer of the children of the revolution,” becomes a symbol of “Venetian citizenship” along with the mayor Selvatico.

It is this person with these ideas in the post-unification context who in 1894 managed to get the City Council to vote on the resolution establishing the “Artistic Exhibition,” a culturally and economically visionary operation in late nineteenth-century Venice, that affirmed the will to make the “public powers” agents of social and cultural transformation. For Selvatico, Venetian modernity had to have roots in solidarity, in the well-being of the citizens, in the redistribution of wealth, in economic heterogeneity. The resolution from 19 April 1894 established that the Municipality of Venice would open “an Art Exhibition every two years” which would promote and support “the economic growth of Venice” gradually establishing it as “one of the most important centres for the art trade.” [14] In the same session, the Council decided what was Selvatico’s main objective: “to allocate any proceeds to city charitable institutions.” [15]

Riccardo Selvatico died in 1901, shortly after the inauguration of the second edition of the Exhibition, and the left wing would not return to administer Venice until the Liberazione. The narrative of Riccardo Selvatico’s life has been built exclusively around the mythology of the “mayor-poet” because, as soon as the council changed, all the reforms he had implemented were buried, considered too progressive and democratic and along them also the founding principle that the Exhibition had been established as a public charity. City politics preferred “liberalism and economic individualism that allowed private speculation and the exploitation of common wealth.” The founding act of the Selvatico Art Exhibition, instead, established how a public cultural institution, located in a specific context, had the duty to bring wealth in both economic and educational terms to the citizens. The statute of the Exhibition in fact provided that the mayor was its president, who therefore decided the political orientation, an essential element for establishing the cultural direction.

Speaking of realizable utopias, of being realistic in order to “demand the impossible,” I would like to tell a little but potentially revolutionary story that proposes the possibility of a reversal of perspective to begin to “think backwards, in a furious act of imagination.” We can start this story a few steps away from the Municipality of Venice, when in the same period in which it signed the agreement with Qatar, Venezia c’è, a “group of citizens representing the Venetian cultural ecosystem in various capacities,” started a signature drive to support the petition asking to open a discussion with the municipal administration on the issue of the management of the Venice pavilion.

Very briefly, the Venice pavilion is owned by the Municipality, and was built in 1932 as part of the “colonization” [16] plan for the island of Sant’Elena, which included setting aside an area for the Biennale right from the first projects because, by the mid-1920s, the building space in the gardens was no longer sufficient, and it was not possible to satisfy the numerous nations that requested a pavilion. The central body of the building was intended for the exhibition of Venetian Decorative Arts as part of the institutional rethinking of the Volpi presidency and the direction of Antonio Maraini who, in line with the fascist ideology, envisaged the diffusion of “Italian decorative taste abroad.” Maraini explains that the name “Venice Pavilion” underlined the “local character” of the production that would be shown. The decorative arts exhibitions continued until the Biennale suspended all activities in September 1942 due to the war. With the support of the Ministry of Popular Culture—which had moved to Venice due to its proximity to the centre of the Italian Social Republic (RSI)—in September 1943 the Istituto Nazionale Luce [17] obtained temporary use of the pavilion to make it a sound stage, becoming the official headquarters during the RSI period. After the Liberazione, the pavilion returned to host decorative art exhibitions until 1972 when the section was abolished with the new statute. Since 1976 the Municipality has made the pavilion available to the Biennale to host nations without exhibition space [18] and from 1982 to 1990 it became the venue of the German Democratic Republic so much so that for a long time it was called the “former pavilion of Germany”. Then the destination of the pavilion becomes more and more confused between municipal management and that of the Biennale: first the official press office, occasionally for exhibition use by sponsors, then managed by the General Directorate for Contemporary Architecture and Arts (DARC)—to make up for the official Italian participation suppressed in 1999 with exhibitions of works that would have become part of the collection of the MAXXI under construction—and in 2007, with the opening of the official Italian pavilion, it returns to municipal management. The intention was for the pavilion to return to the purpose for which it was built, that is, exhibitions that had strong roots in the territory in an international context. But the municipal management of the pavilion, decided directly by the mayor of Venice, has proposed a series of projects that speak a different language to the one spoken in the context in which it is located, but does not even speak to the city in which it is located.

In September 2024, Venezia c’è wrote a certified letter addressed to the mayor to propose to open a reflection and establish a dialogue to clarify the cultural mission of the pavilion, to consider an official statute to establish criteria that are now indecipherable, and to ask that it be equipped with a scientific committee “that restores the heterogeneity of the cultural system in the perspective of plural dialogue.” As the signatories of Venice c’è write, “in the last ten years, the cultural ferment of the Metropolitan City has been growing and expanding. New realities (…) open all year round and managed by people who live in the city, carry out valuable work—often not very visible—contributing significantly to the creation and maintenance of a vital system through the exchange between artists, operators and the public. Thanks to this socio-cultural fabric, the city is gradually opening up to innovative experiments in the direction of a rapprochement between the city’s international cultural institutions and the local artistic panorama, demonstrating the fact that artistic production in this territory is qualitatively relevant and deserves to be supported both at a production and exhibition level. To support this virtuous trend, we believe it is urgent to trigger a choral reflection (…) to develop a series of measures aimed at strengthening the role of the Venice Pavilion as a leading exhibition space in the representation of the city’s cultural context sensitive to the languages of the contemporary and open to the world.”

I would add to this request of Venezia c’è, the symbolic importance of the “restitution” of this space to the city, which is seeing the unstoppable sell-off or privatization of its public spaces due to bad public administration. The restitution of the Venice pavilion to the professional management of the cultural workers who work permanently in the city and who already speak the same language of that context but locally situated, could be a first gesture by the institution and the city to compensate and to “acknowledge historical injustices and create new forms of cultural stewardship.”

The mayor has never responded to the request for dialogue of Venezia c’è, which he probably perceives as a nuisance given that it does not bring any economic return. The narrative of a city that is dying and that cannot sustain itself and must sell itself off, is constructed by bad local public administration in order to take advantage of the “economic liberalism that allows private speculation and the exploitation of common wealth.” Simone Weil wrote that “the greatest misfortune that can happen to men is the destruction of a city” and in a play which is not by chance entitled Venice Saved, she writes that the city is a “human environment of which we are no more aware than the air we breathe.” When there is civil participation, it means that the city is vital, and Venice is increasingly inhabited by people who have chosen it, who see its potential and defend it from bad public administration. Overturning what is possible today and making it impossible, is what this city does daily when i.e. it challenges and defeats large ships with punts. [19]

We must be realistic, use all our imagination and overturn what is possible today. Why is it possible that Qatar can obtain permission to build a new pavilion on a restricted terrain owned by the city of Venice, and that it is impossible for an already existing, historical municipal space, to be managed by local cultural workers who would create projects that speak the same language as the context in which it is located? As Riccardo Selvatico argued, it is simply an issue of political will which coincides with cultural will.

To become the “dreamers of the day” we must be aware of these facts, as conscious citizens we should be watching out that the “public power” works for the commons good, because “those who dream at night wake in the morning to discover the vanity of their dreams. But the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, capable of acting out their dreams with their eyes open until it becomes possible!”

[1] “…make the impossible possible? We should start thinking in reverse, that is, how to make what is currently considered possible, impossible…imagination becomes fundamental…a slogan written on a wall in ’68 in Paris said: ‘To be realistic is to demand the impossible’: which is exactly the furious act of imagination that is required, unless we are happy with the current situation,” Maria Nadotti, L’immaginazione è potere, in 40 anni dopo la legge Basaglia, Convegno Nazionale, Iseo, 10-13 maggio 2018.

[*] I am referring in particular to the history of the Biennale during the reform period, between 1972 and 1975.

[2] Favaro T., Trovò F., I Giardini napoleonici di Castello a Venezia: Evoluzione storica e indirizzi, Libreria Cluva 2011, p. 37.

[3] Legge n. 1497, 29 giugno 1939, “Protezione della bellezza naturale”, pubblicata sulla “Gazzetta Ufficiale”, n. 241, 30 giugno 1939. The law is named after its proponent Giuseppe Bottai (1895–1959), Governor of Rome, Governor of Addis Ababa, Minister of Corporations and Minister of National Education.

[4] Ministero per i Beni culturali e ambientali, Decreto ministeriale, 1 agosto 1985, cfr. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1986/02/06/085A5778/sg published on “Gazzetta Ufficiale”, n. 223, 21 September 1985. Italy was one of the first countries to include the protection of the landscape and the historical and artistic heritage in its Constitution. It did so with Article 9, therefore one of the fundamental principles that affirms the responsibility of the State and citizens to conserve, protect, and pass on to future generations the landscape and heritage that are common goods. A mission that belongs first and foremost to the State, which must protect, and even before that, it must ensure that the rules that protect these goods are respected.

[5] The law takes its name from its proponent Giuseppe Galasso (1929-2018), president of the Venice Biennale 1978-1983 and Undersecretary of the Ministry for Cultural and Environmental Heritage 1983-1987.

[6] This constraint was incorporated into the Lagoon and Venetian Area Plan, approved with a Regional Council Provision no. 70 of 9.11.1995 to which the General Regulatory Plan of Venice for the Old City has been confirmed. Giunta Regionale, delibera n. 7091, 1986, “Piano di Area della Laguna e dell’Area Veneziana (P.A.L.A.V.)”. https://www.regione.veneto.it/web/ambiente-e-territorio/p.a.l.a.v.; Variante al Piano Regolatore Generale (VPRG) per la Laguna e le Isole minori, ai sensi e per gli effetti L. R. 61/85 e L. R. 80/80 anche ai fini adeguamento al Palav, approvata con Delibera della Giunta Regionale del Veneto (DGRV) n. 2555 del 02/11/2010 https://www.comune.venezia.it/it/content/vprg-la-laguna-e-le-isole-minori.

[7] Comune di Venezia, Assessorato all’Urbanistica, Piano Particolareggiato “Giardini della Biennale,” Fascicolo B – Progetto, Norme tecniche di attuazione, allegato alla delibera di approvazione del Consiglio Comunale di Venezia, 20 settembre 2001, p. 3. The Piano particolareggiato (detailed plan), is a public initiative urban planning tool used to specify and make more detailed the provisions of the General Regulatory Plan.

[8] “Promulgated in 1938, the first article of the statute permanently changed the name of the institution by removing the dust from the previous Belle Époque denomination and decline it in a futurist key by placing emphasis on its characteristic temporality: ‘La Biennale di Venezia Esposizione internazionale d’arte.’ That’s when it famously became “the Venice Biennale” for everyone. But how many are aware that the very name of the institution is a fascist legacy? This coincided with the moment the Biennale became a public institution, and this is why I refer to it as the “International Art Exhibition”—although I still wait for a new denomination to be found, more appropriate to the times”, Cfr. https://www.neroeditions.com/the-responsibility-of-a-cultural-institution/. I would also like to add that the name “Giardini della Biennale” (Biennale gardens) is misleading because it indicates a possession that is not real because they are a public property.

[9] The research constituted the sound part of Antoni Muntadas’ installation, On Translation: I Giardini which was located in the center of the Spanish pavilion at the 51st Venice Biennale.

[10] “Due to the problems of space, the Australians abandoned the first project which consisted in the construction of a permanent pavilion in masonry … The building was entirely designed in Australia and sent, piece by piece, to Venice where it was then assembled in the Giardini…” (…) “After the construction of the Australian Pavilion, the area of the Giardini was declared no longer suitable for further constructions. Nonetheless, in 1995 Korea constructed a pavilion despite the fact that official authorization had not yet been issued…The Korean pavilion was the last to be built inside the area of the Giardini…The Monuments and Fine Arts Office and the Venice City Council proposed to furnish the area on which a small brick building existed. Originally, it was the location of the public restrooms of the Giardini. The conditions set down for the construction of the Korean pavilion in the designated area, included the reconstruction, at Korea’s own cost, of the public restroom structure in another location in the Giardini and with respect to its original design and size.” cfr. Martini V., “Pavilions in pills for speaker”, Antoni Muntadas. On Translation: I Giardini, Spanish Pavilion, 51st Venice Biennale, unpublished.

[11] The Italian Constitution, art. 21, guarantees the right to freely express one’s thoughts in any form

[12] Consiglio comunale, “La Gazzetta di Venezia”, 3 agosto 1895. Consiglio comunale. Proclamazione del Sindaco e della Giunta. Baccano indiavolato, “La Difesa”, 3-4 agosto 1895. The first proposal for the celebration of the National Anniversary for Italian Unity on September 20 (anniversary of the Breccia Porta Pia, of the liberation of Rome and the end of Vatican’s temporal potency), was presented to the Camera dei Deputati in May 1889. It was only in July 1895 that it was proposed that September 20 be called a “holiday” to “celebrate the fifth anniversary of the Breach of Porta Pia. Italy’s greatest victory has benefited the entire civilized world”. The national holiday of September 20 is officially suppressed by the decree of December 30, 1923 n. 2859 that changed the date of a series of national anniversaries, introducing new celebrations of the fascist regime. This holiday is replaced, by the date of the signing of the Lateran Pacts, on February 11th, introduced as a civil holiday.

[13] The chamber of labor was born in the last decade of the 19th century, as one of the instruments of the struggle and the disoccupation of the Northern Italian Party, in the period of the economic depression of the decade 1887-1897, as the emanation of the leadership of the Italian Workers’ Party, which subsequently transformed into the Italian Labor Party, then renamed the Italian Socialist Party.

[14] Lamberti M. M., Le mostre internazionali di Venezia cit., p. 101.

[15] Prima Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della città di Venezia, illustrated catalogue, Premiato stabil. F.lli Visentini 1895.

[16] Archivio Storico del Comune di Venezia, n.74247 Ufficio lavori, anno 1928, Colonizzazione dell’Isola di Sant’Elena.

[17] The Stefani press agency was based in Salò, on Lake Garda, and issued exclusive press releases and press releases from the RSI, each of which began with the place (Salò) and date.

[18] In 1976, Colombia and Iraq shared the exhibition space, dividing the restoration costs; in 1978 and 1980 it was granted to the People’s Republic of China, which was participating for the first time. From 1982 to 1990 it became the pavilion of the German Democratic Republic, which in 1986 signed a rental agreement for the Venice pavilion with Biennale for a period of nineteen years, an agreement notified by the municipality of Venice, owner of the building.

[19] Decreto-legge 20 luglio 2021, n. 103 (in “Gazzetta Ufficiale” – Serie generale – n. 172 del 20 luglio 2021), coordinato con la legge di conversione 16 settembre 2021, n. 125.