Do You Feel Safe Here?

On “Tell Me How It Ends/Cuéntame como termina”

Tell Me How It Ends/Cuéntame como termina is a collaboration between Sara Leghissa and Giulia Palladini based on the book Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions by Valeria Luiselli.

a las y los estudiantes

de la UAM Cuajimalpa

proyecto Fronteras:

gracias

We arrive at the beach in the late morning. The sky in Tijuana is clouded, the color of the sand is very pale. There are dogs wandering around the wall: the border separating those few meters of sand on which we are standing from the soil of the United States. We have seen the wall for the past twenty minutes on our way to the beach: its presence completely saturates one’s horizon; it fills the gaze to the point of suffocation. As any border, for that matter.

We drove alongside the wall and we were told by the taxi driver that the wall existed before Trump. During his first presidential term he had only made it bigger, more theatrical, igniting more hate and making the distance clear, revealing the threat, and the materiality of border violence. Still, almost everyone we spoke to, in Tijuana, has a relative who made it to the other side: someone who swam across the border (the “wet shoulders”), entered legally and then somehow ended up staying, or else never made it back. Some people, as a matter of fact, find themselves in Tijuana in a condition of waiting: they are waiting for an opportunity to cross, invent a life on the other side, or somewhere there perhaps. Some of them have travelled a long way: they walked across Central America, crossed rivers filled with mud, and survived for days with very little water or food. Most of them experienced innumerable abuses during the journey across Mexico, on the part of criminal organizations often colluded with the very people who charge a fee to guide the migrants during their journey across the border: those known as the “coyotes,” sometimes including in their services also the promise of an “enganche” once on the other side—a possibility of recruitment in the US labor market. The migrants invest most of their savings hiring a “coyote,” and they have little or no possibility of escape once they embark on the journey. The 80% of the girls who cross Mexico migrating towards the United States are raped along the way.

Yes, read that again.

The 80% of girls who cross Mexico migrating towards the United States are raped along the way.

Some of the migrants have brought along all their belongings, or perhaps just the things indispensable to them, what they could carry or could not let go of. Walking along the beach, that day, in proximity to the wall, there was a family from Guatemala who had mounted a tent as a temporary shelter. An old man was reading a newspaper sitting outside the tent, and close by there were two geese, behaving as if they were in a little lawn, in front of a house. I suppose that they had travelled with them, but it seems unlikely. Perhaps they just met and settled with them on the beach. Others migrants stay a while and make home, although precariously, in Tijuana: they get by doing informal work like selling sweets, cutting hair, cooking arepas, working as riders for Uber Eats, or Didi. Some of them have changed their mind about crossing to the US, in the meantime, and would rather go back home: however dreadful was the context they were fleeing, sometimes it seems more desirable than a life spent waiting. But they have no money to go back home, and sometimes neither papers, as they were stripped of them along the way during assaults.

And then there are children. Those who travel with their parents, and sometimes appear outside of the tents, playing football or swimming, or those who embark on the journey on their own: those defined by the law as “unaccompanied minors” crossing the U.S. Southern Border alone, whose number in 2024 amounted to more than 120,000. We do not know them; we hardly see them. It was perhaps even hard to imagine them when we started thinking about this project: when we wondered how to amplify stories we were not even told, some of which are forever lost along with the life of those who have experienced them.

It was October 2024—just a few days before Trump’s last election—and in the days prior to our visit to the beach it had become clear that obtaining permission to attach posters on the wall between Mexico and the United States was going to be complicated. The day the performance was planned had almost arrived. Sara was on her way to Mexico from Italy, already, and “we” were a group composed by myself, the director and producer of the festival Pasajes /Passages [1] (taking place in between Tijuana and San Diego, in the quixotic, perhaps impossible, effort to explore this space as one, as a continuous city across the border) and a small but incredible team of students of the Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana from Mexico City, who were taking care of the production. We discussed what to do, and decided to go ahead anyway, and realize that the performance was scheduled in the festival even without permission. Simply, it would not be advertised. There would not be posts, leaflets, or promotional material. It would just happen, communicated by word of mouth, and encounter its spectators in the very same way the wall does: just by standing there, being an object of contemplation, sorrow, desire, anger, nostalgia. It would hand itself over to a casual encounter, it would find its spectators in transit, as perhaps it was always proper to a project thinking about transit. If the police arrived, we would explain that this was a festival organized by a public university (true), that we were all students doing a research project on migration, that there was no offence. That this was, after all, simply literature.

I took some pictures on the beach and sent them to Sara before her arrival, showing her through the lens of my eyes, those of that day, the place we had imagined for so long, and for which we had constructed a site-specific intervention: Tell me how it ends/Cuéntame cómo termina. It was a work based on Valeria Luiselli’s book with the same title, put in dialogue with the powerful device Sara has developed in her performance work, involving the construction of an ephemeral dramaturgy of words, fragmenting and recomposing conversations usually recorded with specific communities, through posters populating the public space. When I proposed to her to develop together a project exploring her dispositive for a site-specific performance at the border in Tijuana, I wondered which voices we could possibly convey, and how to reach them, how to translate them —literally or metaphorically. How to cope with the impossibility to reach the voices of an innumerable number of bodies who can no longer speak: whose numbers populate newspaper titles, they are mentioned during political propaganda, they appear as newsflash on social media, daily, but remain uncountable and unaccountable.

To me, the strength of the device Sara has developed in her work is not only that it makes visible thoughts and expressions usually not granted a place in public, but also that it intrinsically denounces (and acknowledges, celebrates) the intimate plurality which stands behind any form of writing, the glimmering conversational nature of an oral discourse which suddenly gets rewritten. So much so that one is encouraged to reflect on all the conversations the space itself shields, on all the words inhabiting the walls as decaying traces of voices that once passed by, marked their surface, persist as scars or maybe presages of future encounters. So much so that this device uses the body—its actions, its fatigue—as a human amplifier for a language which is not extracted from other bodies, but it is returned to its collective nature, to its value as common property. If the initial impulse and technique at the core of Sara’s projects like Will you Marry Me? was recording the conversations she had with groups of people, I wondered how this could translate to a context in which Sara had no familiarity with, whatsoever: not simply because she did not speak Spanish, had never visited the border, had little orientation in both the history of this territory and the jungle of disparaging, or self-invented epithets which over time have crowded the vocabulary of this particular stories: among them, words like pollos [chickens], braceros, wetbacks, undocumented, cholos, chicanos, pachucos, jainas. But most importantly, because the nature of this work, or so I always thought, is not to inscribe itself violently onto a space, extracting its resources, but to conjure and facilitate a collective effort of reading what the space itself has to say, something which is always contingent, made of bodies who cross it and bodies that stay once the performance is over. An invitation to reading words that, after all, Sara never knows in advance, but collects meticulously in an effort of learning, and perhaps thinking what public education, after all, might possibly look like. This gesture, or so it seems to me, is moved by the ethical imperative of what Mexican writer Cristina Rivera Garza has called a “poetics of disappropriation,” referring to “a writing practice in which the texts and experiences of others play a visible, almost palpable, role” and the author’s responsibility is not just to sign them, but to return them to their multiplicity, to their fundamental anonymity, to their private secret and public resonance, to a constitutive revolt against any form of appropriation. While Rivera Garza primarily focuses on the aesthetical processes sustaining disappropriation in writing, in this case—when writing happens no longer on the page, but as a durational cut and paste, as a discourse that is spoken through its own image in a new context—there is an opportunity to ponder on the nature of writing itself, and even more so on the part that reading has in any writing process.

We decided, then, that we needed to trust the process of transformation which any writing has always already undergone, potentially containing promises to the future. We needed an imaginary bridge on which to stand, and listen to the echoes of those voices, a text which could lend us a language open for reactivation, amplification, for a translation which was both a learning and a phantasmatic embodiment. I proposed Valeria Luiselli’s Tell me how it ends: an Essay in Forty questions, a little book collecting the stories the author learned working as an interpreter for the New York Tribunal, translating a questionnaire made of forty questions addressed to unaccompanied minors who crossed alone the United States. Questions such as

“do you feel safe here?”

“why did you come to the United States?”

“did anything happen on your journey to the US that scared you or hurt you?”

“how do you plead?”

The unaccompanied minors mostly hand themselves over spontaneously to the police as soon as they cross the border. Some of them are kept in detention centers at icy temperatures and inhuman conditions for days before being allowed to enter the country, and be processed. All of them need to find and pay for a lawyer within the legal frame of 21 days, and have the chance to apply for asylum only if and when they can prove that they have been physically abused: if they can show their scars as evidence of their stories. These are some of the things we learned navigating through Luiselli’s text. The forty questions she writes about, however, are already filtered, in the book, through her literary voice, speaking from a position of self-declared privilege, as a Mexican citizen residing in the US with a regular Visa, being processed with some annoying delay in that very tribunal where she offered her services as a translator. And yet, her voice strives to be porous, in this book, it makes itself spoken through the voices of others, without ever making them “others.” It neither exposes them to reification: the children are many, they are a multiplicity of singularities, they are in no way a repetition of one another, but the incarnation of an enduring suffering. The unknowability of this suffering is kept intact. What literature does, here, is to offer its pages as the support for stories which otherwise would be unheard, but it does so, crucially, without speaking for those who could tell them. What we could do, then, was to enact a double technology of disappropriation: bringing back the crowds that phantasmatically populate Luiselli’s writing, redistributing this writing among unknown crowds who may possibly continue or recognize those stories.

In her most recent work, Sara had already experimented the potential of her device in relation to written text: for example, in her performance Muscles (also employing the canvassing technique) based on Kathy Acker’s Against ordinary language, the language of the body. And yet, the choice does not seem accidental. To anyone who has read a page by Kathy Acker, it cannot go unnoticed that her writing is never singular: it always strives for exposing the plurality which gives it a body, the nods of the life experiences she conveys—those of the people she coexisted with, she shared sex, troubles, and pleasure. It is a writing that always already decomposes the order of discourse in which an author’s voice can be considered fully “proper,” or reclaims its place as singular. By absolute coincidence, Kathy Acker happened to end her days in Tijuana, close to the world’s most crossed geographical border, hospitalized for cancer treatment, as many other North American citizens who do not have strong health insurance, and to this day can hardly afford medical care in the United States. By absolute coincidence, or perhaps not at all, Kathy Acker is after all one of the authors Rivera Garza discusses in her writing on “disappropriation”: someone whose work persistently exposed not only the violence through which the figure of the author has historically concealed the complex relations of exchange and coexistence always informing any writing, but actually disembowels the materiality of those relations, making them palpable, loud, rendering visible the unpayable debt that any writing has towards life itself.

It is with all this in mind that we embarked in constructing the dramaturgy of Tell Me How It Ends, choosing to dwell not so much on the authenticity of the stories Luiselli collected, but on the images that somehow lingered on the language she chose to tell them, on those words which kept haunting us, obliging us to stop, to read again, to read out loud.

“The 80 % of girls who cross Mexico are raped along the way.”

How to stay in there, before that sentence, how to invite others to do so? How to make visible, almost in a geological exercise, all the layers already accumulated on all those sentences, as much as on the statistics we are quickly presented in everyday reports about migration? How to fuel streams of blood back into the anesthetics of news distribution? How to redistribute this writing, while interrogating the very function of writing before the immense horror produced by border politics?

The day the performance took place in Tijuana the beach was a completely different scenario than the one we had encountered before. It is a glorious sunny day, and the space is populated with all sorts of life, or perhaps just a life painted in different colors: street vendors with pushcarts were selling mangos, chips, beer mixed with Clamato, colored strings they proposed to enlace in customers’ hair, making little braids. The students suggested buying some of those strings to patch together the wooden boards we had brought along, on which Sara’s canvassing would take place, as the wall turned out to be too slippery even for words. The beach was crowded and looked joyful. There were people disguised as Mariachi, playing music and inviting passersby to take a picture with them, in front of what now is seemingly one more landmark of Mexican folklore: the infamous border with the United States. Through the cracks between the little sticks making up the surface of the wall, one could glimpse the beach extending itself on the other side, in the United States: a space of absolute void, silence, suspension, broken only by occasional tours of a police patrol inscribing its passage upon the sand, surveilling, that is, the immaculate emptiness of the beach existing in a space now called San Diego.

We are a little nervous, as there are a number of policemen wandering around: they carry heavy weapons and their boots trample on the sand around our uncertain steps, a few meters from the tents that are still there, in the proximity of many people who are there, waiting, in the vicinity of the wall. We soon realize that the policemen are not interested in us at all: their presence is another performance, aiming at making visible what in the cheerful sun of that day seems almost unthinkable, obliterated. Someone tells us that they have been called by a migrant family from Venezuela whose dog had launched itself into the sea, and started swimming to the other side: they wanted help in rescuing it. The policemen look at the horizon and talk among themselves, ignoring everyone else on the beach.

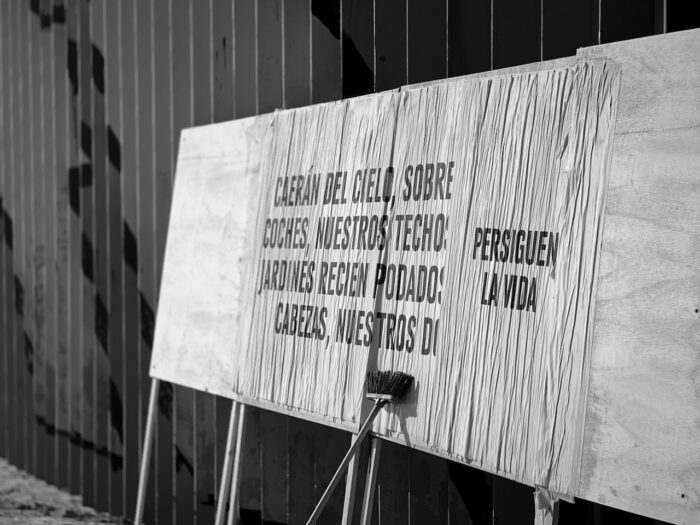

When we walk towards the wall, carrying the wooden boards, the posters and a few buckets of water previously mixed with glue, the sun is so strong that we can hardly see any face. Sara reaches the wall, and prepares her labor: she is wearing her costume, the orange shirt (sometimes a tracksuit) that in all her canvassing performances transforms her body into a vehicle of words, making manifest the plural presence of those who almost disappear, in the cities, during their daily labors of making our walls speak, through postering.

She starts. Sentences keep appearing, one after another, the black ink of the words almost dissolves in the continuous effort of reading, words blur and recompose, meaning and sense blur too, and recompose. The sun has no mercy: it envelops the scene as a ferocious curtain which leaves no escape. Sara is sweating, while she handles the posters, her hands are sticky and struggle to keep the paper attached to the boards. The latter seem stable, they occupy and claim all the space: for a short moment (about 45 minutes, in fact, the duration of the performance) the wall becomes a gigantic page, and there is an open invitation for all to read.

Slowly, this starts happening. Not just the students, our friends, the other artists participating in the festival, or those who had been told by word of mouth that an action would take place in that site, at that time. But also, the vendors, the children playing football in front of the tents close by, the policemen with their heavy weapons. They, we do not look like an audience, but rather make up a scattered, shattered landscape of attention. Perhaps this makes me wonder what an audience looks like, in fact. Because at times, indeed, it feels as if an audience has always, essentially, looked like that: as a scattered, shattered landscape of attention. For a dense moment the sweat, the sun, the noise of the US tank patrolling the beach on the other side, stand still. There is no possibility for those words to go back to a temporality of haste, to disappear in the pixels of our phone screens, to leave space for other colors than the black on white saturating the present of this gigantic language appearing before us. We are making an effort to read, and we need to agree on a common rhythm, the one Sara is gently constructing with her gestures, we cannot turn the page faster or slower.

The dramaturg’s voice in me tells me that the piece is too long: we should have maybe cut the story of those two girls whose grandmother sewed a ten-digit phone number on the collar of their clothes, the number of a relative already living in the US which the girls were supposed to show the police once on the other side, hoping that this could help making a case for family reunification. Maybe we should have cut, instead, some of the repetitions, like those “Do you feel safe here?” which again and again appear on the wall, as a refrain that in its absolute silence slowly becomes a deafening question. And yet, on that beach, that day, it suddenly felt as if that endurance, that fatigue, the constant sweat dripping across Sara’s back, her physical effort to make space for those words, for allowing them to persist in time, necessarily called for a mimetic solidarity: the bodies who were witnessing it, who were reading the writing, needed to endure too, surely they had the possibility to walk away but they did not, and so—as it happens—the space for words of others was made possible.

The words, for instance, of a young Colombian boy carrying a backpack, who stood close to me on the beach and little by little started commenting on the sentences appearing on the wall, and inserting in them bits of his story: the journey which had brought him there, the failed attempts to cross, the plans for attempting it again, or trying his luck otherwise. The words of another man nearby, an Iranian poet who had sought refuge in Mexico many years before and decided to stay afterwards: someone who cannot enter the United States either, but simply does not care. “Why do you want to cross, my friend?” He asked the Colombian guy with the backpack, and told him his story. “Why don’t you take a moment and change your mind? Why don’t you stay in Mexico?”

Another man sat on the side of one of the pushcarts, and started speaking to a mango vendor, who had momentarily suspended the promotion of his product to become an attentive spectator. The man told the story of his arrival in Tijuana from the South of Mexico, many years ago, about his addiction to crack, about the organization who had helped him clean up and for which he now worked. He then tried to sell some postcards and magazines from this organization, little papers which he held on his sweaty hands while keeping his eyes on the wall, on Sara’s hands on the wall, on the words which were once spoken by someone and then written by other hands on a screen, then printed in large format, now saturating the horizon of that very moment.

I don’t remember the end of Sara’s performance. I am not sure how it became apparent that the pile of posters on the sand had disappeared, and the stillness of that moment simply translated into a gigantic question, impossible to ignore, one which was destined to keep inhabiting the wall, at least for a while, even after we would be gone:

“porque viniste a Estados Unidos?”

“why did you come to the United States?

One of the forty questions the unaccompanied children are routinely asked, for sure, but one which somehow sounded completely different, now, when read on the other side of the border, and not only because of language. The political posture Rivera Garza calls disappropriation responds to an impelling effort, on the part of writing, to maintain the inscription of the other (the body who is not there, no longer, or perhaps not yet) not only within the writing itself, but in a place undermining language’s supposed authority. This is a condition, even more than a choice, which is unavoidable in the time which Achille Mbembe has named necropolitics: a situation in which contemporary states have absolute sovereignty not only on life, but also on death. In this state, it is not only human life that is kept under control, considered disposable, annihilated, but the very human condition on which life can be even thought, spoken, and possibly redeemed.

I don’t know how long the writing survived on the wall: perhaps a few hours, perhaps a day or two. We received a picture the following day, featuring tourists posing in front of the question alongside the disguised Mariachi. I tried to imagine what we would have said if the policemen had asked for explanations for our actions, that day: we would call this activity a moment of learning, inscribed in the values of public education that Mexico has long defended. We would not be lying. We would perhaps invite them to think with us what learning, in fact, actually is, and what is the place of writing, on the page and on the desks, in the university and on a borderline beach.

The intimate plurality of that common reading, of that afternoon of sweat and sorrow under the Tijuana sun has disappeared as a presence. Its traces on the wall keep operating as scars, maybe presages, prompts to the exhausting, and inexhaustible, telling of ever new stories, especially those which never got to be written.

[1] Rodolfo Suárez Molnar and Soledad Amido.