Architecture of Anger

In solidarity with Santarcangelo Festival and against the commodification of dissent

What happens when anger, once a force of clarity and communion, is no longer feared by power but quietly absorbed, aestheticized, and rerouted? This essay reflects on the architecture of contemporary rage, how it is no longer suppressed, but instead saturated, diffused, and redirected to fragment solidarity and disorient resistance. Beginning with the symbolic dismantling of Santarcangelo Festival in Italy, it moves through the quieter mechanisms of authoritarian control: the withdrawal of cultural space, the commodification of dissent, the erosion of relational trust. It asks what remains when protest becomes spectacle, and how we all might still choose to carry our anger not as rupture but as relation. Against the slow violence of distraction and fatigue, it proposes the unfinished labor of staying with each other, of coherence, of care, and of collective attention, as a radical counterforce to the system that thrives on our disconnection.

In this moment of political decay and social fragmentation, I return to a persistent question: What is the architecture of our anger? Is it the pulse of our collective yearning for justice, the residue of unfinished revolutions, the cry of the dispossessed refusing to disappear? Or is it something else, something intercepted, manipulated, and ultimately deployed against us by the very regimes we seek to resist?

Anger, historically, has animated movements, ignited revolutions, and fueled the construction of new political imaginaries. It has served as an effective bridge between personal pain and structural analysis, transforming individual despair into collective action. But today, under the shadow of resurgent fascism, neoliberal cruelty, and algorithmic governance, anger has become a contested terrain, not just expressed, but engineered. We do not merely feel anger. We are made to feel it, relentlessly, performatively, and often aimlessly. It is not simply suppressed, it is saturated, flooded and reproduced.

Authoritarian regimes have long known that anger is not dangerous in itself. What threatens them is anger that clarifies. Anger that gathers and anger that endures. And so their tactic is not to silence it outright, but to reroute it: to make it self consuming, to turn it against kin and community, to ensure it burns inwards rather than through the structures of domination. This is not incompetence. It is a method.

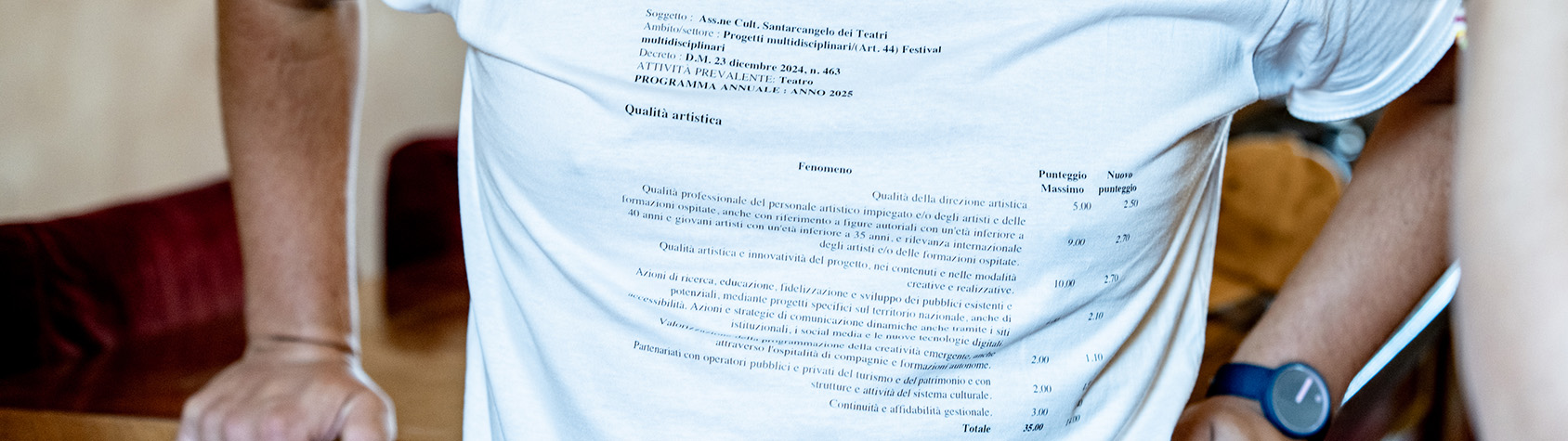

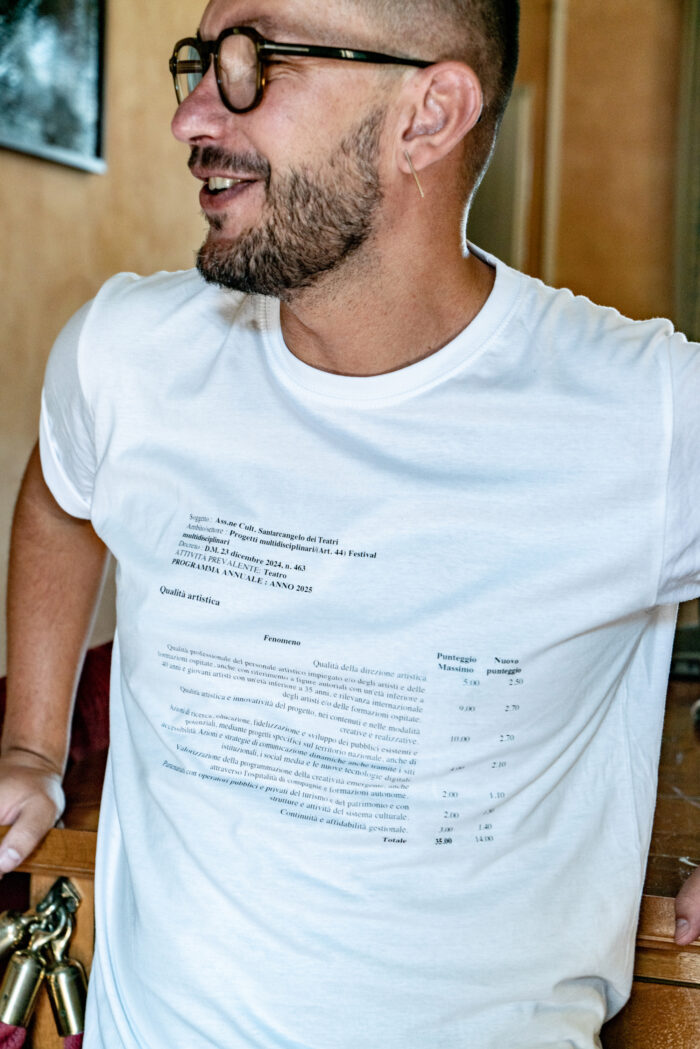

We see this clearly in the cultural sphere. In Italy, the recent defunding and symbolic devaluation of the Santarcangelo Festival is not merely a withdrawal of resources. It is a message. An attempt to discredit and invalidate the power of imagination itself. A move to destabilize one of the few remaining spaces where collective thought, dissent, and alternative socialities are still rehearsed. Authoritarianism today rarely announces itself with spectacle, it prefers the quiet efficiency of administrative violence, of creating docile bodies and automatons.

This dismantling is mirrored by a broader affective regime, in which rage is aestheticized and commodified. Through digital platforms and spectacle driven politics, anger circulates without rest or repair. We are pulled into a loop of reaction, never resolution. We are made to burn, not to build. This is the cunning of control. Anger is not repressed, it is absorbed. Its edges dulled, its direction blurred, its energy converted into distraction. What remains is a din of outrage, dislocated from memory and disarmed of consequence. And when anger is severed from historical consciousness and collective care, it implodes into self surveillance, horizontal blame and movements that unravel under the weight of their own unprocessed wounds.

In such conditions, even care becomes vulnerable. Solidarity becomes a spectacle. Trust becomes too slow. All the while, the machinery of fascism refines itself, not through chaos, but through calibration. And yet, what possibilities remain open to us?

Perhaps it begins with a refusal, not of anger, but of isolation. A decision to carry our rage into proximity. To treat it not as an endpoint but as a threshold. To return it to those it was taken from: migrant workers, invisible laborers, borderless bodies whose survival continues to expose the cruelty of the world. To be in relation with those who are disappeared by systems is not charity, it is resistance. And to resist together is to remember that no structure of domination is eternal.

Fascism thrives in the failure of community. It expands in the gaps left by broken trust. But what it ultimately fears is coherence, not of ideology, but of attention. Of tenderness. Of people who still choose to stay with each other through uncertainty and indifference.Can anger still hold us together, rather than pull us apart? Might we tend to it not as a blaze to be feared, but as a quiet ember that warms our capacity to remain with one another? In a world that thrives on disconnection and exploits fatigue, what forms of attention and tenderness can still endure? If fascism fears coherence more than noise, perhaps the most radical gesture now is to remain proximate, to stay in relation, and to keep imagining otherwise, slowly, stubbornly, together.