Sleeping Today

Sleeping and dreaming groups all over the world united against 24/7 capitalism

Curated by Lýdia Pribišová, the exhibition What is happening with sleep today? places sleep and its possible, but at the same time impossible commercial use in today’s society at the center of its reflection, taking inspiration from the text of the art historian and essayist Jonathan Crary 24/7 – Late Capitalism and the ends of Sleep, in open controversy with the dehumanizing conditions dictated by neoliberalism and non-stop productivity which leads to a life without pauses and a sort of a “global slumber.” A condition that is redesigning the notion of temporality, outlining new and extremely dangerous strategies for the surveillance of individual subjectivities which undermine the possibility of individual political expression and dissent. Here, Ben Landau investigates the incidence of sleep in contemporary society. Sleeping and dreaming open a connection with the unconscious now neglected by our hyperreal world, placing itself as a last bastion of freedom from the incessant pace of work.

Its 2014 and I’m holed up, almost alone, at a residency in the outskirts of Vienna. I’m a social being—I rely on the spirit and conviviality of shared experiences: any visit to any boring place is better with a friend. Here, no one is social. We even eat alone in the timber paneled kitchen, perched on the edge of the Viennese woods (where I imagine famous psychoanalysts have strolled).

My room doubles as a studio, where the outlook is over a broad grassy expanse. All the studios (of the often absent artists) face the same direction so we rarely see another soul. It’s cold outside, but heating makes it cosy inside, to read and watch films in the bath. I stay in.

In my isolation and self reflection, I enter deep states of listening and watching the minute details of the world pass my window, drifting in and out of sleep in my cosy hideaway in the vienerwald. My dreams are vivid—perhaps spurred by the heat in my room and my dislocation to an unfamiliar territory. Occasionally falling in or out of sleep, wondering which is more real, I ponder over what work I should be doing, and how the cycle of sleep is (re)generative. If I sleep more would I work better?

My interest in sleep leads me to Jonathan Crary’s book 24/7 – Late Capitalism and the ends of Sleep, which notes the decrease in sleep and changes in sleep patterns since the industrial revolution. My rumination on Crary’s text extends not only to the temporal changes in sleep, but on the altered meaning and value of sleep. Like Michel Siffre, a speleologist who used his own experience to experiment with sleep cycles, I want to use my own sleep cycles and subconscious to ruminate on possible active and divergent sleeping practices.

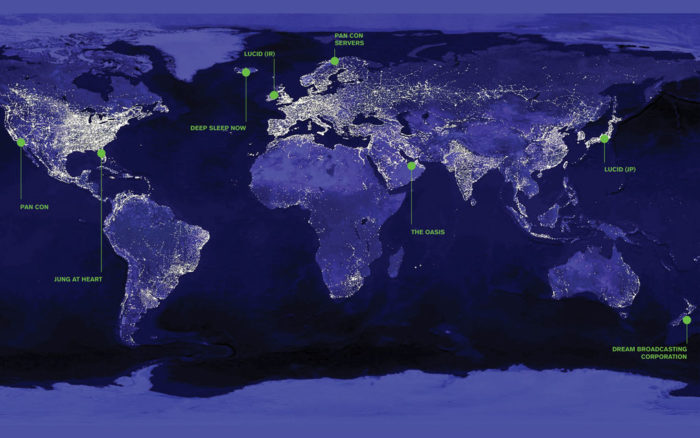

In a daily rhythm, I travel in and out of the city researching groups around the world who innovate in sleep, and most often linked to dreaming—an untapped “resource.” Mostly, I find interesting groups who sleep more rather than less. I call them Sleeper Cells. In the evening, I return on the rattling train and walk up the winding road past Aldi, in order to sleepresearch further, putting myself in the shoes (or on the pillow) of my fellow slumberers.

Ben Landau, Sleeper Cells, 2014.

On a chatroom somewhere, I find PANCON, founded in 2003 in California. It’s a company which seeks to record the unconscious in digital form in preparation for singularity, the tipping point when computers will attain consciousness and surpass the capability of humans. Sleep and dreaming plays a large role in how PANCON records and processes the individual’s unconscious.

Sister ventures like Alcor Cryonics enable wealthy individuals to be cryogenically frozen and re-animated when the technology becomes available. Together with PANCON, other companies glean data from conscious sources, such as voice recordings, diaries and the whole history of social media. Along PANCON, they speculate they will be able to reconstruct “ghost images” of people’s identities and (un)consciousness. These cutting edge research/startups spur each other’s research and development, and will ultimately work together in the (post-singularity) future when their clients are re-animated.

Julia Gryboś and Barbora Zentková, The Shallow Sleep of Emergency Mode II, 2019; installation view, AlbumArte, 2019. Site-specific installation with sound piece. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano, courtesy AlbumArte.

PANCON’s speciality is in interpreting and collecting unconscious brain patterns through non invasive methods, and conducting studies to further understand the large data sets they hold. Like Alcor, they are a partially speculative-technology firm which wealthy clients fund their speculative research on, and are both the subjects and beneficiaries of the research.

Technologist Ray Kurzweil invented the term singularity and is one of its greatest proponents. He has elected to have his head cryonically preserved at death. Kurzweil has stated that he would prefer a digital form of consciousness rather than biological, which is susceptible to ageing and decay. I wonder if he has also considered PANCON’s services to retain his unconscious self, given that he considers himself a human computer just waiting to be downloaded.

Delving into PANCON’s FAQs and forums, I begin to piece together their client services. It seems that different membership fees give either shared or individual access to an MRI machine, in order to record unconscious (sleeping) brain patterns. These recordings are stored and interpreted. Techniques such as associative recording may be employed, where brain activity is matched with the dreamers’ recollections. The client who sleeps in the MRI machine is woken in the depths of dreaming to record the contents of their dream. This data is cross referenced until patterns emerge which associate certain brain activity with specific content which is re-checked against dream diaries etc.

The highest level of membership offers a personal MRI for the client to sleep in nightly, and unlimited offers to take part in interpretation services as they are offered. The more a member sleeps, the more will be recorded, and the more their unconscious forms how all unconsciousnesses are interpreted.

Another less invasive technique is Decoded NeuroFeedback, which takes place while the client is awake, and uses correlation between visual imagery and brain patterns. For instance, the client is shown a silhouette of a dog, or the smell of a rose, and the subsequent brain patterns recorded. After, when the individual is asleep, recording brain patterns can give a pixelated version of their internal visual processes. The effect of these studies is cumulative, so that on reviewing the correlations between recorded neurofeedback and remembered dreams, the brain strengthens these connections and dreams and their recordings become more vivid.

Julia Gryboś and Barbora Zentková, The Shallow Sleep of Emergency Mode II, 2019; installation view, AlbumArte, 2019. Site-specific installation with sound piece. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano, courtesy AlbumArte.

On my train journey home I drift off and wake up two stations further out of town, and have to take the overpass to the other platform and stand in the cold, to retrace my steps back to the residency. There is a significant shift from sleep to wake, and from a warm cosy rattling train compartment to the desolation of this outer urban platform.

Shivering in the still air, I correlate the strengthening loop between computer and brain to my increasing dream memory through keeping dream diaries. They are vivid depictions of snapshots of my life in Vienna, moments of indecisions, revivals of old friends and half remembered faces. I wonder what it all means. To further my research (in the birthplace of psychoanalysis) I decide to research further into the sleep theories of psychoanalysts—and head home to bed (to work?).

Martin Kohout, Slides, 2017, installation view, AlbumArte, 2019. Single-channel video (22’51’’ min.) Photo by Sebastiano Luciano, courtesy AlbumArte.

On this train of thought, I stumble across a group far from Vienna—Jung at Heart—a senior social club in Miami, USA, created by renowned Jungian Psychoanalyst Benjamin Robin. The club lives in a nursing home of the same name, and share experiences with dreaming in a group. Instead of a regular one-to-one Jungian psychoanalysis model, the group helps each other decode their dreams and delve deep into their unconscious.

In an email conversation with Robin he writes that older people sleep more, but don’t necessarily dream. Their sleep is shallow and fitful, similar to that of an infant. They don’t enter into “normal” triphasic sleep like younger people do. But with the help of diet, vitamins and some mild sedatives, they can be assisted to sleep better.

Jung at Heart’s members aim to sleep 12 hours a day, a bit short of the 14 hours I’ve recorded with other groups, but as most people over 75 years old sleep less than 6 hours a night, this group double their average, and I include them in this survey of sleepers.

Robin goes on to tell a great tale of the nursing home’s role in the retrieval and publishing of Jung’s Red book, an account of his unconscious adventures in the early 20th Century. With many WWII Jewish emigres in the Jung at Heart cadre, the connections through to Vienna and to Jung’s estate were significant. It was partially the gentle encouragement, and largely the groups revenue raising which enabled the book to be finally published in 2009.

In contrast to PANCON, which effectively mines the unconscious for useful brain imagery, Jung at Heart have a simple aim, to collectively reflect on the group’s dream states as an exercise in self-empowerment, and ultimately to vibrantly relive their more active lives. Their dream state can be their preferred state, or as one participant wrote to me “the ebb and flow between sleeping, waking and talking about my dreaming lulls me back to sleep.”

Ben Landau, Sleeper Cells, 2014, installation view, AlbumArte, 2019. Single-channel video (2’40” min.) Photo by Sebastiano Luciano, courtesy AlbumArte.

I completely relate to these generous older folk, as they explore sleep communally towards the end of their eventful (and sometimes traumatic) lives. I feel they themselves may be more connected to their younger happier selves than I am to myself now. Through recollecting my dreams in a diary (and experimenting with dream enhancing supplements—more on that later) dreaming has begun to register as one of the highlights of my day. It’s a cycle that I relish and try to find ways to fill my day with peripheral imagery which can spark interesting connections in my subconscious. It’s easy to become obsessed with an idea, and soon my internet feed is filled with diverse digital offerings to supplement my evening explorations.

Ben Landau, Sleeper Cells, 2014, installation view, AlbumArte, 2019. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano, courtesy AlbumArte.

One which I become fascinated with is the Dream Broadcasting Corporation (based in New Zealand) which was the first group to compile films and audio which, with their recommended supplements and dreaming aids, help spark vivid dreams. Today, they are like the Netflix of sleeping—you can watch something while falling asleep which will impregnate your subconscious and trigger certain dream-journeys.

The first videos they created were released through Youtube, but since have launched their own specific service. Most videos are 40 minutes long, with 10 minutes of images which are delivered in quick succession (bypassing the conscious, but lodging firmly in the unconscious). Synchronised with these images is audio which, after the 10’ video is replayed repeatedly for the remainder of the video (the screen is blank) to create a soothing rhythm. As the viewer falls asleep this audio cycle infiltrates the dreaming state with the intent to influence the dream.

I try a one month trial subscription to the service. There is something unnerving about falling asleep intently watching a screen. They do offer Virtual Reality videos, but I don’t have a headset, and sleeping for the rest of the night with it on freaks me out a bit.

The DBC has split subscription offerings into a free section with few dreams (with advertising) and a paid premium channel for advertising free dreaming. Contrary to other video streaming services, DBC suggests that users do not choose their dreams, as this impacts the unconscious uptake of the content. Rather, subscribers can give DBC access to several tiers of information, from taking several personality tests to allowing full access to personal images, music, search history, email exchanges and social media engagement in order to select dreams randomly. Not knowing the content beforehand bypasses the conscious brain.

Delving a little deeper into the terms and conditions of DBC, I found that they only oblige themselves to acknowledge advertisers in product based advertising. If Coke want to feature in a dream, this is acknowledged in the prelude of the video. However for non-product based advertising, like an experience, service or even something as broad as a desire or life goal, DBC will make dreams for advertisers without acknowledgement. For instance, they might create a dream video about the joys of having children for an IVF clinic or an Icelandic travel dream for their tourism bureau. DBC research shows dreams featuring generic experiences over specific products may increase the dreamers desire for that experience rather than sating their craving. These videos are the dreaming equivalent of “advertorials.”

One venture of DBC is gaining ground faster than others—their offerings of dream supplements. Skeptical question whether the pills work, but like any magic potion, they sell like wildfire. In the comments section of a Wall Street Journal article, one commenter reveals that lab tests (in a research paper I cannot access) on DBC pills have found common dream-aiding chemicals and suggests that DBC rebrands existing pills. I order some and try them out (without much discernible effect).

On the horizon for DBC are dream videos created using machine learning. These mine subscriber’s personal data to weave their histories in with their unconscious and create the most powerful and personal dream videos to date.

Ben Landau, Sleeper Cells, 2014, installation view, AlbumArte, 2019. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano, courtesy AlbumArte.

My initial interest in DBC is how they’ve managed to literally tap into people’s desires and combine it with technology to create a thriving business. However, it leaves me feeling uncertain, as their advertorials take advantage of the vulnerability of the unconscious, and just like a social media platform end up turning to advertising for their primary revenue. The subscriber model is problematic. Like many digital services DBC users fall under the maxim of “if you’re not paying for it then you’re not the client, you’re the product being sold.”

The business side of things is fascinating though. As I collect my stipend from the residency office, I also consider whether I myself am working: being paid to understand sleep and dreaming. I wonder if I’m making more progress on my sleeping research in my waking hours or when I’m dreaming. Perhaps in response to DBC, I avoid digital devices when going to sleep, and definitely when waking up. In the mornings I try and keep an hour or so to slowly wake and allow my unconscious thoughts to galvanise. My work on sleep and sleep on work.

Julia Gryboś and Barbora Zentková, The Shallow Sleep of Emergency Mode II, 2019; installation view, AlbumArte, 2019. Site-specific installation with sound piece. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano, courtesy AlbumArte.

There are others in a similar rhythm, though their topic of investigation is not sleep itself, but subjects determined by clients. These highly specialised ’dreamers’ are employed by Lucid, a business self styled as a “dream tank” based out of Dublin, Ireland and Kyoto, Japan. Lucid applies the unconscious to create and extend concepts for entrepreneurs.

Lucid hires dreamers with high beta one frequency band of brain activity (which indicates an ability to lucid dream and recall dreams). Potential employees undergo a testing phase which monitors their brain activity when exposed to “inputs.” I assume these “inputs” are delivered in a similar method to the DBC, where videos and sound introduce ideas which are then impregnated in the unconscious. However, the specifics of these techniques are not detailed by Lucid.

I trawl through the FAQs on Lucid’s website, where they address Dreamer applicant questions. Dreamers all sleep at the lab headquarters in Dublin. They are given personal rooms to make their own, which often become filled with the content of the client they are dreaming for. Dreamers must sleep alone, and are mostly single. Lucid demand them to abstain themselves from drinking and caffeine, to exercise and stay healthy. It is not necessary to quit smoking, in fact, the presence of nicotine in the blood increases dreaming so many non-smokers use patches. Dreamers meals are catered and include foods with high levels of vitamin B6. Lucid details that dreamers can be specialists in right or left brain thinking, but gives no more information about how this is assessed in dreams.

Dreamers have relatively few benefits such as paid leave or healthcare. In a little more online digging (in facebook conversations with ex-dreamers) I find that some even work a second job during the day. Most dreamers are young and work for 2 years almost full time, before they take another avenue of work. All content fed to the dreamers in the period before they sleep is confidential, and any information or ideas generated while the dreamers work is considered the property of Lucid and their clients.

It strikes me that Dreamers are almost like elite sleep astronauts or “somnstranauts” who prepare and venture deep into dreams, searching for new ideas as if they were new planets, and bringing back samples into the waking world.

More scientifically, Dreamers practice both “active” lucid dreaming and “reverie.” Active sessions work iteratively and in short bursts on given content—so that the next steps of a business or project can be detailed and rested. “Reverie” requires much looser input and can generate giant leaps forward. It is considered as the “genius mode.” It generates fewer, risky, long term ideas. Dreamers often work on one project at a time, and are assigned adjacent clients in different fields to maintain confidentiality.

The entrepreneurial side of Lucid is based in Ireland, which has favourable tax, intellectual property and work rights. It’s also a hub for artificial intelligence research and human interface computing.The scientific side is managed by Yukiyasu Kamitani, formerly of the ATR Computational Neuroscience Laboratories in Kyoto. Kamitani pioneered connections between brain imagery and computers. However, for now, most of the dreaming in Ireland is through recollection of the Dreamers themselves, not computer neuro imaging.

A new service offered by Lucid is dreaming retreats. Entrepreneurs pay to ‘be a dreamer’, and live in the Lucid headquarters. They eat a dream inducing diet, and are assisted to create personal environments within their room which reflect the challenges of their complex projects. From reviews, it seems that these retreats have mixed results.

Ben Landau, Sleeper Cells, 2014, installation view, AlbumArte, 2019. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano, courtesy AlbumArte.

Some part of me can’t believe Lucid is a functioning startup, or that clients pay to have someone “dream” about their business proposals, let alone visit an inner city dream “retreat.” The world seems inverted—in the past when I was busy, I felt guilty about sleeping and often tumbled into bed exhausted. At Lucid, Dreamers work as they sleep. Do they feel lazy if they wake up early?

My Facebook conversations with Lucid ex-dreamers fuels a rising despondency with the capitalist instrumentalisation of the unconscious. The chats coincide with my own experimentations with multiphasic sleep patterns, where one can sleep for shorter time, in 20 minute bursts every 4 hours. Now, I’m alone in the Viennese woods at 4:20am, with no-one to talk to, nothing to do, nowhere to go, and I can’t fall asleep or the experiment will fail. I flip-flop between wondering which I want to maximise—my hours of sleep or wake?

Julia Gryboś and Barbora Zentková, The Shallow Sleep of Emergency Mode II, 2019; installation view, AlbumArte, 2019. Site-specific installation with sound piece. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano, courtesy AlbumArte.

My blog on sleeping experiments starts to get some traffic and even comments. One is from an artist I met at a past residency. He’s Icelandic, and recommends I check out an anarchist group in Reykjavik called Deep Sleep Now. I’m skeptical, and even fatigued by the choice of “how to sleep.” But I have another month left, and after some (waking) hours away from the sleep project, I get in touch with Deep Sleep Now, and find that we have more in common than I thought.

Deep Sleep Now (DSN) suggests that extended sleeping is ultimate autonomy and the only feasible and attractive de-growth strategy. They advocate for sleeping up to 16 hours a day as a method for active and accessible de-growth, for autonomous unconscious and sustainable living in a post energy world. De-growth is primarily an ecological movement which seeks to limit the damage that humans have had on the planet. It is anti-consumerist and anti-capitalist with its roots in The Limits to Growth report, published in 1972. Deep Sleep Now particularly observes how the experience economy has increased the disposable nature and wasteful practices of the growing international middle class.

DSN live collectively in an unfinished apartment building in downtown Reykjavik where they sleep, eat and drink communally. They’ve occupied this building since the end of the 2008- 2011 financial crisis and have retained squatting rights since. Their bunk room and living quarters is made from recycled materials. Collective members sleep in shifts, which add up to 16 hours dreaming a day. They try to maintain a binaural pattern of sleeping 8 hours, awake for 4, and then 8-4 again. This pattern is offset with other members, to maximize social contact with different people.

The main premise of sleeping longer is that they are not awake and active for as long, and therefore limit their consumption of the earth’s resources. They use sleep to investigate their deep unconscious which also replaces much of their need for fulfillment through unsustainable travel, consumption and entertainment.

Deep Sleep Now grow much of their food through permaculture and aquaculture in greenhouses heated with geothermal energy. They live with chickens who help process their waste and provide a protein source (eggs). They also eat a lot of mushrooms, grown from spores. They grow perennial herbs high in Vitamin B6 which help them dream vividly. One food source which is essential to their diet is wakame and kombu seaweed, which they labour-trade with Thorverk, an industrial plant which collects and processes seaweed. Seaweed is the highest known vegetarian source of tryptophan which assists in lucid dreaming.

DSN suggest that living in Iceland presents the closest possible approximation of what it would be like to live in a post energy society, where electricity is almost unlimited. They also acknowledge that Iceland is perhaps the only place where this experiment can happen today, as geothermal energy provides much of their energy (heating and electricity) needs. Meanwhile an internal debate on Nuclear energy circulates within the collective.

In the times between sleeping, members of Deep Sleep Now take part in important social bonding sessions which help to bring human contact. They also spend time tending to the vegetables, and recording dream diaries.

Of course, their 16 hours sleeping, combined with their high B6 and tryptophan diets give them lots of experience in deep and controlled dreaming. As a demonstration of their ideals with de-growth, they suggest instead of taking a holiday in Thailand, to preload the unconscious with images and sounds of Thailand, and lucid dream the trip instead of taking a flight. Their open source developments of dream leisure are not quite as cutting edge as the Dream Broadcasting Corporation, but are covered by strict creative commons licenses which prohibit advertising.

One collective member (who asked not to be named) suggested that solidarity wavered on specific issues (like Nuclear). They revealed that DSN has a few core members who maintain the original intention of the collective, which can make them conservative in the face of new challenges.

Julia Gryboś and Barbora Zentková, The Shallow Sleep of Emergency Mode II, 2019; installation view, AlbumArte, 2019. Site-specific installation with sound piece. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano, courtesy AlbumArte.

It’s refreshing to exchange emails with Deep Sleep Now. Their responses are considered and generous, and they do not gravitate towards self aggrandisement or eco-martyrdom. There is an intensity to their language which I imagine comes from lots of discussion and consideration, and perhaps collaboratively generated text. The revelation that there are some fissures in the group comes as no surprise.

A question I direct to them, which is only partially answered, is one about privilege. They address it by acknowledging that Iceland is perhaps the only place today where their experiment can be conducted, and elsewhere would require an abolition of property ownership, compulsory collective living and unlimited energy.

I ask this question of DSN because in my sleep research I have found an organization which has a diametrically opposed viewpoint and situation, especially with regards to privilege, and how these two are poised, perfectly illustrates the contradictions present in the sleeping and dreaming landscape.

Julia Gryboś and Barbora Zentková, The Shallow Sleep of Emergency Mode II, 2019; installation view, AlbumArte, 2019. Site-specific installation with sound piece. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano, courtesy AlbumArte.

The Oasis is a resort in Dubai, catering to a privileged few who want to explore the depths of sleep. The resort’s byline is “Dreaming is the Greatest Luxury.” In contrast to Deep Sleep Now, this behemoth of an enterprise is private, exclusive and energy sucking. For every utopia there is an equal and opposite dystopia. The resort offers just under 200 rooms, all fitted with the latest technology hidden behind lush interiors and five star fittings designed to offer perfect sleeping conditions.

Clients can book their rooms by how firm they would like their mattress. All rooms are sound proofed, and can be completely darkened. This allows the space exterior to the dreaming body to be adjusted in any number of ways. The beds are fitted with dreaming pillows which can be scented with different natural oils. Speakers built into the bedheads can be programmed to play specific sounds composed by the inhouse sleep audio specialist, or brought by the clients. Naturally, dreaming visual aids are available on the in-house channel (for advertisement free dreaming).

The hotel runs a true 24-hour service, to cater to sleeping through the day or night. Any meal is available at any time, as are sleeping aids and physical relaxation assistants like masseuses and hypnotists. Most benefits are included in the tariff, but extras include on-staff psychoanalysists, psychotherapists, professional dream interpreters, dream technologists and a tarot reader.

In perhaps the most stark sign of the individualist power of neoliberalism (and in contrast to the collective living arrangements of DSN) many couples choose to have adjoining rooms with a bed in each, to maximize uninterrupted dreaming.

Ben Landau, Sleeper Cells, 2014

There is not much more information online on The Oasis, and to be honest, I don’t need any more. I’ve surveyed a wide range of sleeping and dreaming groups. In this article I have not included some groups where credible information is less available, or suspicious (for instance from Chinese state-based media).

Parallel to this investigation, I’ve experimented on myself like Michel Siffre, trying out the supplements, dreaming aids, sleeping patterns and even a couple of psychoanalysis sessions—all in a bid to understand this sleeping and dreaming world. I’m exhausted by the to-ing and fro-ing between my sleeping and waking states, both being under scrutiny, and my constant sleepwork—whether conscious or unconscious, observed or reflected upon. The groups I have found only further prove Crary’s observation that neoliberalism will instrumentalize any propriety in humanity. Even DIY groups who develop their own open source technology or methodology are unwilling researchers for others who have the desire and the capital to use it to manipulate others.

I’m dreaming of the world when I sleep and thinking of dreaming as I wake. I’m in a sleep version of jet lag, where I am dislocated in time and attention. And luckily my residency is over—I don’t know how else I would bring this research to a close (as I will, for sure, sleep again). I pack my bags, and prepare to leave my tiny Viennese cabin, back out into the world where sleeping and dreaming are just something most people just do, rather than something analyzed, augmented or wished for. The other morning commuters on the train are heading into work, and I’m leaving it. These sleeper cells have inspired me to reconsider work and sleep, reality and dreams, and to be honest, I can’t tell which is which. I’ll sleep on it.