A Possibility for Meeting

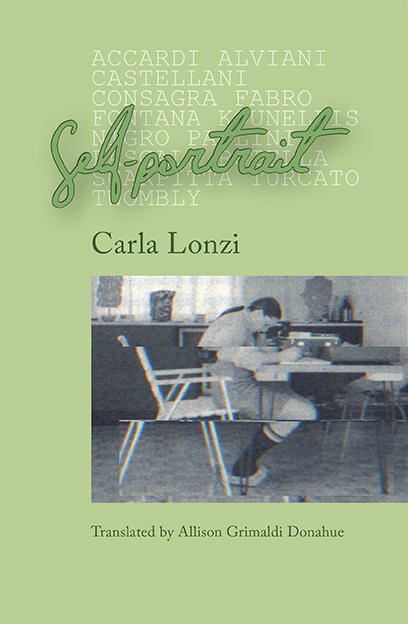

Excerpts of Carla Lonzi’s “Self-portrait” translated by Allison Grimaldi Donahue

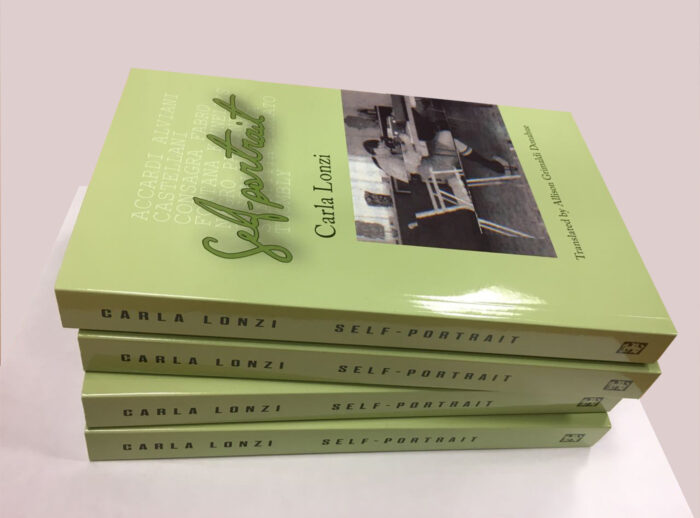

Among other books of hers which have a clearly declared political inclination, Carla Lonzi’s Autoritratto remains a fundamental read for art historians, artists, curators and researchers. In its montage, Autoritratto is applied politics, a critique of criticism, the surface against which the artist genius hits bottom. We are very glad to host an excerpt of the English translation by Allison Grimaldi Donahue, published by Divided Publishing: a short selection from the introduction, and a passage from page 27.

This book emerges from the collection and rearrangement of discussions with some artists. Yet the conversations did not originate as material for a book: they respond less to the need to understand than to the need to spend time with someone in a fully communicative and humanly satisfying way. The work of art felt to me, at a certain point, like a possibility for meeting, like an invitation to participate, addressed by the artists to each of us. It seemed to be a gesture to which I could not respond in a professional manner.

Over these years I have felt my perplexity grow about the role of the critic, in which I’ve noticed a codified alienation towards the artistic fact, along with the exercise of a discriminating power towards artists. Even if the technology of recording isn’t automatically, in and of itself, enough to produce a transformation in the critic, for whom many interviews are nothing but judgements in the form of dialogue, it seems to me that from these discussions an observation emerges: the complete and verifiable critical act is part of artistic creation.

[…]

Lonzi: I wanted to make a book that’s a bit meandering, you know? Because what really bothers me . . . no, what I really like in artists but what really bothers me in critics, where there’s none, is this sense of measure, this moving from one argument to the next. Critics, on the other hand, are always stubborn types. For me . . . I just can’t stand this sense of mind that fixates on one thing. This need to produce knowledge . . . the cultural worker, that one has to work over and over the culture itself, so they become obstinate about pulling something out . . . What do they call it . . . ‘obsessive praise’, the existentialists, that is this imbalance between one’s concrete personality and one’s ideas, to extract all of the possible mental consequences from an assumption and, really, go on to infinity.

Accardi: When someone wants to make a book like this, she’s got to actually put a lot of herself into it, as if it were also a part of her life, you know? You could never do it, Carla, as you want it, I’m sorry, I have to tell you . . . I don’t know, if we’re talking about the level of creativity, yes . . . Now, it is an extremely great leap you are asking yourself to make, or at least it seems to me, because as a creative person, you should put yourself in there as you are in particular moments of your life, do you know what I mean? How can you do that? It’s that, maybe, artists are able to communicate this a bit better, it’s what makes others suffer . . . Maybe, I don’t know, I keep saying ‘maybe’.

[…]

Consagra: There is a barrier between what I myself do, and the others, right? But the artist, I think, today . . . or maybe this has always been the case, transmits himself to others to change their perspective: the artist continually imagines himself as another person who enjoys this thing the artist does. When I split myself in two, I split myself with a non-professional, someone without a profession, I split myself with someone who has a somewhat animal intelligence, a man of sacrifice, though they may be small, all to say, I imagine myself as a guy with a really generic intelligence, who has to live inside the things I make, am I explaining myself? At a certain point, the artist means just this: the man who liked to do that given thing, and the others, who aren’t artists, those who have refused to do this thing here. For the others, it always remains a question of knowledge, of culture, but never of experience . . . it is an experience the others will never have, they aren’t interested in it, if it interested them, they would become artists and they would do it in some way.

Accardi: In an old interview of mine, the one in Marcatrè, you know, I said, ‘I have this urgent need to understand.’ Do you remember, Carla? It’s something vital I carry with me, that surely everyone has: some deny it and close themselves off in their own pride, they no longer have the desire to understand, and so they say, ‘So, what does this thing do? and what does that thing do?’ Whether it’s in politics or in art. Others, on the other hand, have the vital attitude of wanting to understand, to be in contact with things – I am very much part of this second group – but, then, I thought I didn’t much like this thing I said, it seemed too rigid, there was something hungry inside what I said, something controlling, that wants to devour the other. This bothered me for a long time, then I realised that it was important to not let it become a sort of neurotic fixation. If it becomes self-defensive it becomes neurotic, and then, the first thing one always remembers is ‘to try and understand others in order to have control over them’. On the other hand, if one does it a little, doesn’t do it a little, loses interest, you’ve also got to think of the facts of humanity . . . This year I thought of things on a larger scale, I concerned myself with the problems women face . . . certainly I have more love, I don’t know how to say it, because if not, if you always stay there focused on the creative fact, fixed, within a collective, you lose a lot, because you begin to feel the presence of others. This, even as a girl, is something I always avoided, but instinctively . . . I remember I had none of this thinking then, I was completely indifferent to understanding others fully, as is common with young people; I disengaged for a long, long time. Even now I like, sometimes, to think about something for a while, and then really rest, I can even become indifferent to it. And like this, I realised that this understanding between artists can happen at certain times, while at other times, during youth perhaps, you don’t care about it at all. I can feel the indifference in a young person because I can . . . I can remember it. […] And naturally, I am interested in those who are younger than me and have different experiences, they always draw very authentic emotion out of me. So, one night I was disheartened because I got there and I saw Argan, I didn’t know . . . and so I said, ‘What goes on in their heads, calling artists from certain periods, and young artists, and then they call up Argan.’ In Rome these curious things happen: you have a debate about demonstrations and you call Cagli on stage! But let me tell you, how false it all is. Look, it seems to me that in Italy there is actually a tradition of falsity, because people think, ‘It does no harm, falsity isn’t what destroys ideas . . . deep down maybe there are good ideas, new ideas . . .’ No, this isn’t the way. One must be a bit tougher, a bit more puritanical and should say, ‘No, where we find good ideas, new ideas, we can cut them out, we can make a division.’ And it isn’t like someone like Argan needs to intervene, and then be mixed in with critics at random: it’s a mess. It would be better to invite someone who is more tied to the artists, someone with whom they share a personal affinity. For this reason, a debate emerged, that one there, pathetic, from this point on. Why had artists spoken so little and critics rambled on so much . . . I don’t want to add more, it will diminish it. So, I wanted then to clarify: what does the critic do? He does the opposite of everything I previously mentioned, he does everything at random, comments waft about like when you smell a good perfume, a rose and you remember ‘roses exist’, or you go into someone’s studio and say ‘Oh, look at this thought that he had . . .’ But the critic has knowledge locked in a certain phase, in its own neurotic form.

Lonzi: I want to kiss you!