A Pedagogy of Dissent

On protests, monuments, symbols and public space: a conversation with Iván Argote

On June 7th, Iván Argote (CO) presented for Hidden Histories his long-running project Activissime. Created in 2011 and carried out through a series of protest-workshops designed for girls and boys aged 4 to 9, the work is aimed at developing critical thinking through language games and playful demonstrations, to encourage voice empowerment and imagine new paths and ways of crossing and reappropriating public spaces. In Rome, the workshop took the name Attivissimə and took place over two workshop days, with a group of children/participants in the after-school activities of the Associazione Genitori Scuola Di Donato, a reality that constitutes a fundamental point of reference in the Esquilino neighborhood thanks to the initiatives that encourage and consolidate relationships and exchanges among the many communities of different cultural backgrounds that inhabit the neighborhood.

Curated by Sara Alberani and Marta Federici, with Valerio Del Baglivo (LOCALES) Hidden Histories is designed as a platform for site-specific research and artistic production and aims to critically re-discuss the city’s historical-artistic legacy, adopting approaches and methods of decolonial thinking. In this third edition, the focus remains on the public space, a dimension that in Rome is closely connected to the notions of heritage, preservation, restoration, and monumentality, along with its collections, archives and objects that still today are read and valued within a white, patriarchal and heteronormative canon.

Hidden Histories 2022 Trovare le parole / Finding the words takes its cue from an expression by feminist theorist Sara Ahmed in her book Living a Feminist Life (Duke University Press Books, 2016), and focuses on the linguistic dimension as a fundamental space in which to act and declare what is not seen and recognized within society as violent, racist, and sexist. As stated by Ahmed, finding words means naming the problems we are confronted with, “allowing something to acquire a social and physical density by gathering up what otherwise remain scattered experiences.”

The following conversation happened shortly before the workshop.

Giulia Crispiani: Your work Activissime! covers a time span of over 10 years, how did it evolve and how will it be physically iterated here in Rome?

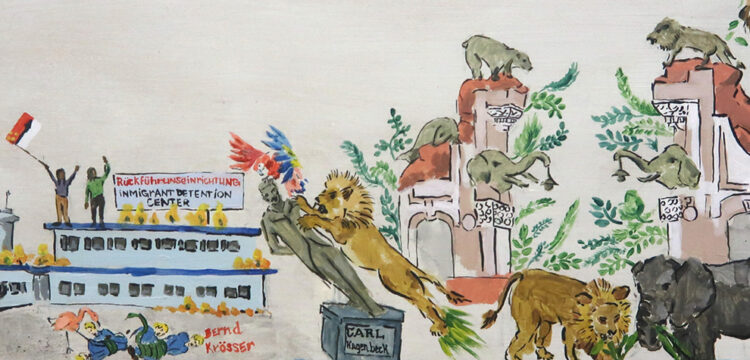

Iván Argote: It all started back in 2011, when I was preparing a big project and film called La Estrategia, for which I collected several stories from the 70s, when my parents were part of a revolutionary group. The idea was to go and live with a group of people under the same rules they used to organize their personal and political life with, so to invent the archives that were never made in that time. It was meant to be like a re-enactment, and at the same time I took advantage of the shooting moment to make some public interventions, precisely on monuments—as a part of fiction.

Eventually, during my research, I found some photographs of my father when he was an elementary school teacher, and he used to teach how to make protests. A few months before the shooting of La Estrategia I was invited by the MACVAL Museum in France to do some summer workshops with children. I thought that was the perfect opportunity to make this first re-enactment, that becomes a direct action. From the archive to fiction, through a real action in the public space—this was the strategy.

Since 2011, I have done the workshop over 20 times, in about 12 cities, each time in a different context, with different durations. We worked for a month with some groups , for instance in Thessaloniki, while with others just for a week or three days, some other times even for a few hours. In Barcelona for example I worked with children who were studying in a school which has been closed by the government due to budget cuts, and we managed to do several protests in the city and inside the abandoned school, including their parents.

When I arrived at Villa Medici in Rome and met the Locales’ team (Sara Alberani, Valerio Del Baglivo & Marta Federici), we started a very natural conversation. Just like them, I work a lot in and about public space, so it made sense to do something together. We felt it could be interesting to bring Activissimə in Rome, with the Scuola di Donato, a very special school in Esquilino. So we approached the school and started the conversation, we met and they liked the idea a lot. I also shared some material about the past experiences, we talked about the specificity of this school and the kids’ background.

Has the subject of the protest changed over time? And how do kids read and interpret politics according to their geographical location? I mean how far do they go in terms of topics?

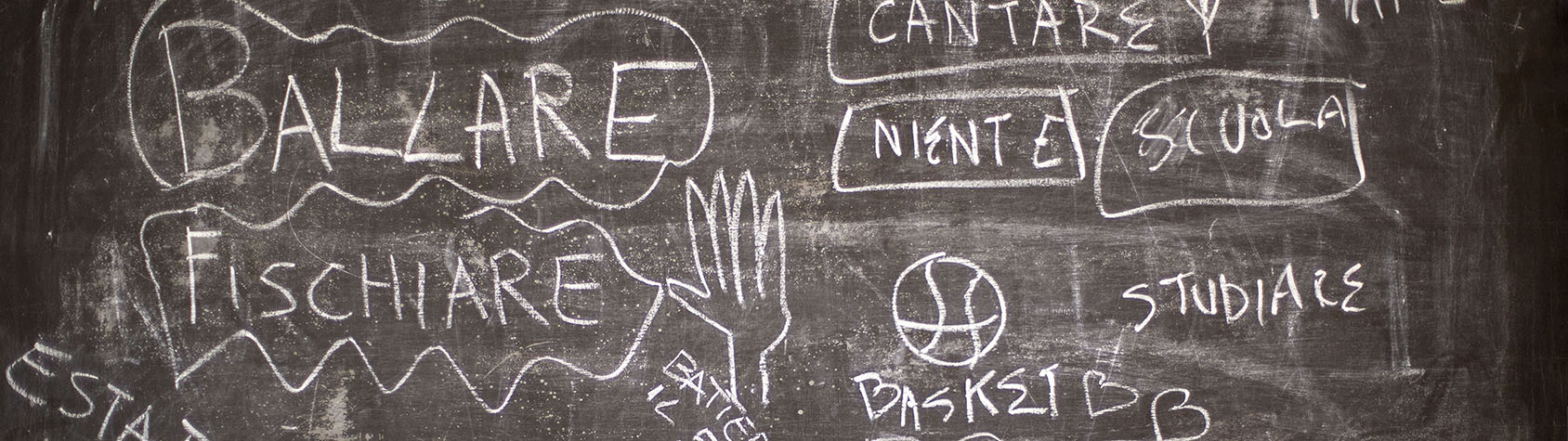

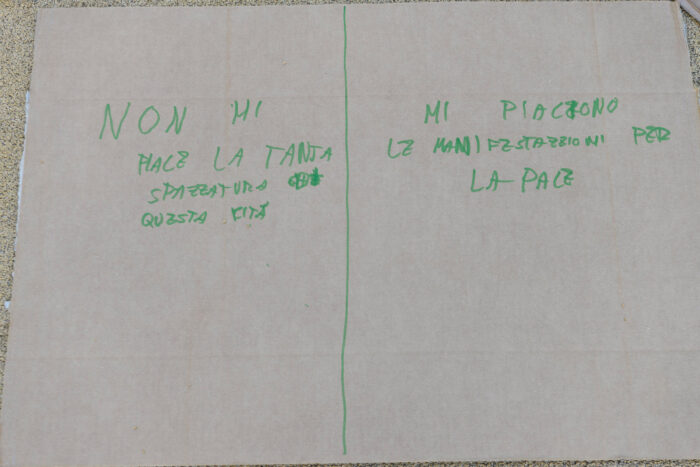

My father used to teach union slogans to the kids. I didn’t want to tell what to say or write. An important (and the longest) part of Activissimə is a writing workshop, where everyone looks for things they like, what they don’t like or would like to change. For me, it’s mostly like a workshop of thought and opinion that is then empowered by outdoor protest. There’s no specific theme, everyone contributes from wherever they want. We talk about games, food, school, the street, the city—about friends, war, difficulties, but also more abstract things. In the first workshop I remember a kid who came up with a slogan saying: “Sleep more to be less tired”. I still think of that and feel it applies to children’s life, as well as to the workers’ condition, I feel it is a poetic and simple critique of the system of production. The kids make slogans about everything, namely the food they like, time management, about animals, about the light—about aliens, music and a lot about dancing. We do dance sometimes.

In each city, the children talk about things they have in common and specific things, like in Cotonou for instance, the girls used to write “Girls should go to school” because from a very young age they are taken out of school to help with the household. In Phoenix, Arizona it was so different, some children talked about money. In Paris, I remember children making slogans saying they wanted to go back to their countries of origin (Morocco, Algeria), or mocking Sarkozy—the president at the time.

You said your father was a primary school teacher and included the protest as an integral part of his teaching. So I’d like to ask you, what is the pedagogical potential of the protest according to you?

My father has always been a true militant, since he was 16, as far as I remember he was always busy with organizing people and making them aware about the importance of engagement. Back in the days he was on an ideological mission, and I believe he thought it was important to discuss social conditions from an early age. Now I know he was right about it. On my side I approached it in a different way, our brains are formed in our first 7 years of life, through the paths we use to build our thinking. Of course we can re-develop it after, but these first years are super important. I think from a very early age we should integrate philosophical questions at school, related to life, love, existence, and most importantly social questions as well. We learn quite a lot, although we rarely learn about questioning things, even more rarely we actually experiment on how to learn in the first place.

As I said, in this workshop there is a big part of thinking and experimenting with language in total freedom. It’s fine to say and ask things, to write them the way we want, to then go out and share those views, outside and out loud. It would be good to learn to keep the intensity of that moment. I have a strong memory of a specific moment in my childhood: once in my elementary school, a very humble school in a popular neighborhood in Bogotá, a university student came to conduct theatre workshops. It was something different, he was also looking different, long hair, and other kinds of clothes. Some of us attended and we made a theater piece together. I don’t remember well what it was about, but that experience was something that clicked many things in my head, and turned many questions into possibilities. I don’t know if that click has happened to any kid in these workshops, but I always think about that experience.

Some of your recent works are dealing with monuments, symbols and public space. How have actual recent protests influenced your approach?

I started doing these interventions on monuments and other related projects back in 2011, with La Estrategia. From a very young age I felt the use of public space was a bit weird, inasmuch as the meaning of the statues. I grew up first in a suburb, half social housing half favela, then at 14 we moved to the city center. So I discovered the “city”, meant as institutions, buildings, squares and monuments. We lived in a place near the city council, with offices, some embassies, and a big University. I guess it triggered me at first because it was odd, then with time I started thinking about the ideological charge of those architectures.

Recent protests in the US somehow brought a lot of attention to our relationships to monuments. I think in my and the younger generation many of us already felt their oddity, and indecency in their honoring of monsters, and celebrating humiliating stories. More importantly, I feel there is a growing awareness about how we as communities are not represented by our nations nor their official histories. Public pace is a place of demonstration, of strength and power—never a place of reconciliation, of questioning. In Colombia, we had a big protest in 2021 against a very cynic and corrupt government, where many social groups and indigenous communities tore down colonial statues, and that was the first time ever this happened. I believe we need other narratives, in our schools, in our history books and in our public spaces.

In your experience, what happens to a protest when it enters the museum space?

A protest in a museum is boring. We have to get out, so all the workshops are conceived for the street. Yes, sometimes we have to work in a museum, or a cultural institution, most of the time I work in elementary schools, and even then the idea is to go out. I never program the protest as a performance, I don’t like this idea of not having a public, so I try no to involve arty people. I like to go in the street and interact with pedestrians, block a street for a while, see the reaction of people, police, people in stores and coffee places.

I feel that works such as The other, me & the others physically embody much of your larger research, as the weight of more bodies who share a common space gets visualized, for there’re always implications, or there were always bodies before politics, or?

The Other Me And The Others is an installation that represents well and easily this idea that we are all linked, that our actions generate reactions as we are in this all together. I don’t know if we are first one thing, then another, I feel we just are so many things simultaneously. We get born in some place, and since then we get—without choosing much at the beginning—a place, a moment, a culture, a social background, and economical context. Politics are always there, at home, in the street, at school, it’s just part of the way we structure ourselves. I feel there should be a different notion to designate the politics of our living, before professional politics, and maybe the second should be more about the first.

What kind of words are there to be collectively found/drafted/revised/shouted? I guess with kids there’s a higher surprise element?

Yes, the most interesting thing about these workshops is that they go toward unexpected places, and the meaning and poetry of the kids’ language, sentences and actions is way more interesting than the device itself. I try to ask the adults and the teachers I work with to not tell anything and not suggest anything. Some teachers say, out of good will, something like—“we should think about ecology”, it’s good and it’s relevant, but this is not what this is about. It’s mostly about being able to generate your own thinking, and then find a way to share it. The second part of it is collective, it entails a more complex discussion. We usually have some debates about gender and other social themes such as education, work, and also about infrastructures, cities, conflicts. Every group has its own dynamic. At Scuola Di Donato we worked with a very diverse group in terms of class and origins, maybe the most diverse I ever worked with, and I am really curious to see what happens when we get to the street!