Witting Vitium, indeed

Madison Bycroft at ADA, Rome

Witting Vitium, Madison Bycroft’s first solo show in Italy is currently on view at ADA. The short film The Sauce of All Order orbits the Augur, an Ancient Roman figure whose job it was to interpret specific signs in their environment, and report their interpretations to the state. The signs included the flight pattern of birds, the pecking of sacred chicken, the direction of lightning, unexpected sonic interruptions (a burp or sneeze for example), as well as the close inspection of the entrails of sacrificial animals. Reading the auspices followed a system and strict codes guided interpretation, outlining what was a sign and its meaning. But misinterpretation was frequent, and at times, even purposeful: knowing that an emperor wanted to go to war, an Augur would be a fool to interpret the gods’ will as otherwise.

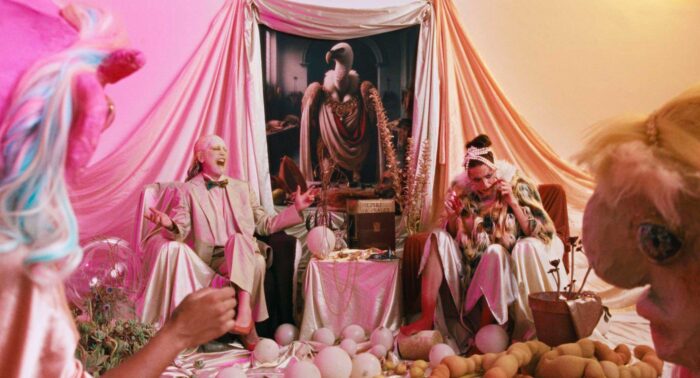

Witting Vitium, indeed. There’s a certain plenitude in Madison Bycroft’s imaginary, which can’t be said to be made of single works, as each piece is made of endless labour, turned into just a component of the perfect scenery for a desired community, a quantum banquet, where history does take another course. Currently on view at ADA in Rome, their work The Sauce of All Order is the result of their residency period at the French Academy in Villa Medici, the sixteenth-century Italian Mannerist villa with its 7-hectare Italian garden, contiguous with the more extensive Borghese gardens, on the Pincian Hill next to Trinità dei Monti in the historic centre of Rome. A very voluptuous venue, with peacocks roaming around, and one of the best views of the entire city. That is the backdrop of the piece, that got me thinking how, at first sight, Madison succeeded in queering up both the epic and the palace, making a sapient use of the residence and the residency. Whilst we are at it, our gaze shifts as history becomes something unfinished we do not take for granted, and as in Madison’s oeuvre at large, all the pleasure is in the details.

I wonder whether the Augurs and the plot came before or after the architecture and the scenography—for those of us living in the city that is such an exotic part of Rome, highly characterized by infernal tourism, romanticized by cinema, and of course, very heavily drenched with classical iconography, in between Fellini’s dolce vita and the very continental ideal that artists should come to Rome to study and copy the masterpieces of antiquity and the Renaissance. Art History with capital H (or, I would stress, HIStory). Although its allure has almost completely vanished, for me Madison’s work was capable of both adopting the iconography and inhabiting the architecture with irony and wittiness, twisting them to a certain unprecedented extent. Along that revision, it is history that has become irretrievably contemporary, and queer—the auspices that are taken feel like pink soft silk.

The contemporaneity of the Augurs—that is those priest who were capable of ascertaining of the will of gods through observation of the sky and of birds—in the time of genocide and denial is also bending straight white time, relativizing the assumptions of normative power structures, and their juridical legitimacy and validity. After all, the empire is still alive and kicking, and we are all dealing with policies that make use of mass media to fold the truth and hide it to manipulate public opinion in favor of necropolitics, surveillance, extraction and militarization. In the film, the college is reunited around an endless supper (again full of details carefully orchestrated by the author) as “the economies of reading (the future) and consumption overlap.” Indeed gluttony and decision making still remain very centralized in the hands of power, inasmuch as power is still castled in palaces. The augural rites were considered as part of the sacred, a way for the gods to let their will known, but still magistrates could devise tricks to avoid being paralysed by negative signs. The main character, Felix, is about to be inaugurated, but as they dig deeper all they find is lies and corruption. Although the mole here is taken quite literally, its validity compresses time, rendering an ancient (more or less religious) convention still quite reletable. In its fascist conception, power is something to be maintained, centralized, and used against opponents. To work towards the dismantling of existing power structures, we all know, one must dig deep.

I was stricken when I learned that also the story of the foundation of Rome is based on augury. Romulus and Remus did act as augurs, and Romulus was considered a great augur throughout the course of his life. So, instead of the classical idea of learning from “the masterpieces of antiquity,” when in Rome, Madison has rather worked them through, deviating them into today, by narrative means, but also by engaging with the local queer community and scene. The (more or less professional) actors are all (more or less) known faces, and to see them in that backdrop gives me a sense of relief and release, as some sort of reclaiming the fact that our future belongs to us—but maybe I am just biased. The function of the augur was central to any undertaking in Roman society including matters of war, commerce and religion, and the “divine will” they were supposed to read would affect peace, good fortune and well-being. I must confess that I have this (more or less religious) belief that artistic practice is a form of divination, in two directions: on the one hand for the images, words or persistences coming to us, and on the other, because of a vision of all possible other pasts and futures. So with Madison’s work, also the fantasy of the present can take another course, as these augurs would never predict in the service of the empire.

Let’s return to the details, as that is where the real epic lies: first and foremost the cover songs we of a certain generation can all recognize, then all characters’ costumes and make up, and again the use of the backdrop that gives a whole new tridimensionality to that “palace.” But the most exceeding to me is the banquet, both for the food that is consumed and how the actors are instructed to consume it, and the crockery—some of which are on view in the exhibition, revealing really to what extent that classical (straight) iconography is totally reimagined anew, as delicate, joyful, vivid, and precious precisely for being so fragile. I won’t spoil the plot that unfolds throughout the script, casually shifting from Latin to English, from monologues to dialogues, that at times are sung and interpreted, or become a talk show meant to tell augurs’ secrets, in that word play Madison is such a master of. Witting Vitium, indeed, it’s all very arbitrarily breaking down History’s machismo, the rationale repeatedly overturned by associations, mirroring, figures of speech, and endless references. The college of Augurs is just an excuse for an exquisite queer soap opera, and once Felix’s real nature is revealed, the whole forecasting apparatus collapses under the weight of truth—although Veritas has already died since the start. And so the mole digs, uncovers, mines and undermines the modus operandi of decision-making in the halls of power, relativising it, if you will, furtively conducting the augury out of the binary.