Why did you make me come over here, then?

Renegotiating sexuality and architecture stemming from Giovanni Testori

Ma allora, perché m’ha fatto venir qui? (Why did you make me come over here, then?) is the fifth chapter of L’Ano Solare. A year-long programme on sex and self-display—a research, exhibition and performative project challenging sexuality and collective practices of self-representation, curated by Il Colorificio. The chapter is articulated in two solo shows, the first by Francesco Tola (1992, Ozieri, SS; he lives and works in Milan) at Casa Testori, Novate Milanese, the second by Giovanni Testori (1923, Novate Milanese, MI – 1993, Milan) at Il Colorificio, Milan, with a text contribution by the researcher Mariacarla Molè (1991, Ragusa; she lives and works in Turin). The project focuses on the multilayered work of Giovanni Testori, investigating the theme of sexuality starting from his perspective and moving away from it, identifying conflicts and discontinuities in his thinking, due to a strongly normative historical and religious context. The two shows question identities and sexual representations connected to or inspired by Testori, building an archaeology of imaginaries and renegotiating them in the light of emancipations and experiences situated in the present day.

Ma allora, perché m’ha fatto venir qui? is a project in collaboration with Casa Testori, the cultural association located in the family house of Testori in Novate Milanese that promotes the legacy of the writer, playwright, art historian and artist, as well as any contemporary research relating to this heritage.*

Prologue

With the literary cycle I segreti di Milano (including the posthumous Nebbia sul Giambellino) Giovanni Testori becomes the voice of the inhabitants of the Milanese suburbs. Testori is the critic who rescued the Sacri Monti—in particular the Sacro Monte di Varallo, described in Il gran teatro montano—from the oblivion of folk clichés, returning their legacy to historical and artistic studies; he was the first playwright who, in L’Arialda (1960), gave space to homosexual love on stage, without falling into stereotypes or turning his characters into caricatures. His homosexuality, which he wrestled with throughout his life because of his deeply-rooted Catholic faith, is a fundamental matter that can be questioned and compared with that of other historical figures who led battles in the Italian public debate. Indeed, in the context of L’Ano Solare, Testori is an unorthodox voice when compared to other critics emerging in the field of theory in the 1960s and 1970s, such as Carla Lonzi, Guy Hocquenghem, Monique Wittig, Mario Mieli and Mariasilva Spolato. However, that is the reason why he offers lateral and conflicting insights, often politically contradictory with the direction taken by L’Ano Solare, but pivotal for understanding the unique human history and cultural humus of Milan during the last four decades of Testori’s life.

The methodology applied to this project has consisted in an in-depth research concentrated on the life and work of Testori, made possible through archival visits at Casa Testori and trips to the Sacri Monti, partaken by Il Colorificio, artist Francesco Tola and researcher Mariacarla Molé. The intention was to recontextualise the “hot” topic of sexuality in Testori—“hot” since it didn’t encounter neither the interest of Catholic Groups supporting the author, nor the attention of the italian homosexual movements because of Testori’s conservative positions and therefore he hasn’t been thoroughly explored. Re-examining sex and anality in Testori—as physical and conceptual devices of disidentification and transcendence of gender and sexual orientation—can be relevant today in order to re-read the author, updating his grammar and imagining hidden practices such as cruising—which seems to emerge in some of his works—and thus tracing a space of queer possibilities. Ma allora, perché m’ha fatto venir fin qui? is the question that, in the tragedy L’Arialda, Lino asks Eros, wanting an explanation for their choice of meeting in the dark fields around the quarry. The play, written by Testori and directed by Luchino Visconti was censored in 1960 and withdrawn after the show in Milan in 1961 “for turpitude and triviality” and for the story of a gay couple. The accusation implied in the question entails something unspoken or misunderstood, a dimension of illicitness and a fear of stigma. Sexuality is presented in the scene as something unexpected, that leaves one puzzled—a prelude to a scenario made up of possibilities that require choices and, to this day, shared societal responsibilities.

Since both shows share a trans-temporal enquiry, they also bear the same title, imagining that the artists have tried to answer the same question, inaugurating paths that are both divergent and consonant.

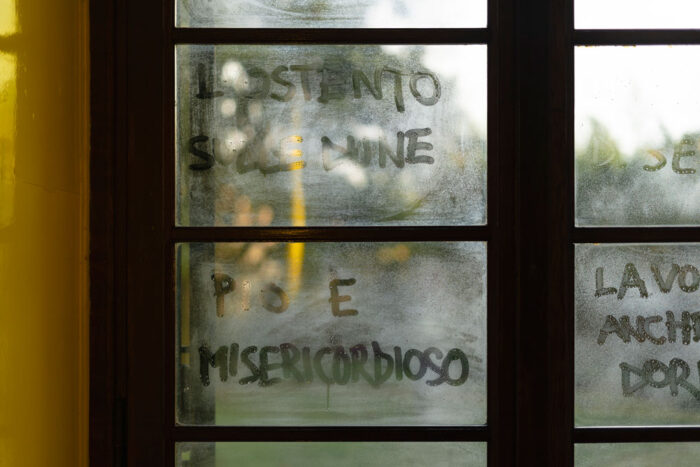

First Act – Francesco Tola

Francesco Tola’s exhibition recognises in Testori’s literary production certain recurring patterns connected to sexuality. In his plays Testori generally avoided the translation of sexual urges into scenes and, when he did it, they were concealed in the darkness of a quarry, among the hedges of a field hidden between factories, obscured by the fog that swallows the outskirts of Milan. Sex occurs far from the domestic walls, often in nature, following a mostly monogamous proto-cruising practice. Tola approaches Testori’s family house—recalling the hearth of the Northern Italian productive bourgeoisie, which in the 1960s were witnessing the beginning of an economic boom—in pursuit of an inversion of spaces: he proposes a semantic structure that opens a gap (an anal-architecture), physically letting the outside in and, thus making room for those desires that, although recorded, could not take the shape of images. This way, Casa Testori is no longer comfortable and bright, but stands as an unrealized version of itself, transforming Testori’s echoes into ghosts that reclaim its architecture. Tola’s installation unfolds in two pivotal rooms of the house: the living room and the veranda that leads to the garden. The large living room of Casa Testori plunges into a blanket of dense fog, intended to conceal all bodies below the waist. The mist is both a syntactic device aimed at bringing inside the nocturnal atmospheres of the encounters described by Testori, and a caesura. It reveals a space of possibilities below which sight is ineffective, where rationality and morality make room for drives and desires, that allow us to dispose of our own selves. A suspended video installation is presented inside the room. The film shows images shot on the beach of Platamona, in Sardinia, occasionally frequented by families and a destination for sexual encounters and cruising. The subjects chase a weak phone signal through the Mediterranean scrub hoping to find their partners using digital Apps. We catch glimpses of sunburnt skins and backs, a dance of bodies anxious to welcome the other, hungry for each other’s recognition. And yet this recognition remains distant. In a diachronic and explicit parallelism, what Testori seems to be implying in his drawings actually happens: a slow dissolution in the polymorphism of one’s own desire. In the veranda the lighting turns the room yellow, wrapping it in a soft warmth. On the three French windows opening onto the garden, an intervention turns the glass opaque, as if it were coated in condensation. A hand-written poem covers the misty glass surface: the narrative follows the structure of the window frames and inhabits this liminal architecture to tell the story of a suburban boy who explores his sexuality by giving himself to others, until he reaches the beach at Platamona. Casa Testori becomes opaque, a no longer luminous interior, home to the rarefaction of spontaneous encounters and, at the same time, the transition of condensation from gaseous to liquid state. The small drops that separate the new inside from the outside reveal the composite temperature of the exhibition that contains, like a Testorian oxymoron, the coolness of invisibility and the warmth of bodies.

Second Act – Giovanni Testori

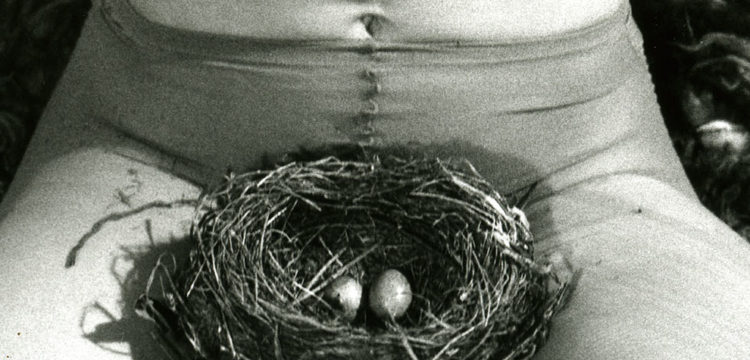

Testori’s drawings hang on the wall like stations of desire. They are portions of bodies, limbs and fragments of sexual organs that emerge from indistinct and indecipherable backgrounds: they look like poses illuminated by flashing street lamps in the darkness of the night, or anatomical studies obtained by placing genitals, buttocks and breasts on the backlit glass of modern Xerox photocopiers. Made between 1973 and 1974, they were exhibited the following year at the Galleria del Naviglio: cocks, vaginas, asses and tits are placed next to ripped rabbits, lilies and philodendrons, nothing but meat portrayed in its bloody nudity. In the text of the catalogue published on the occasion of the exhibition, the critic Cesare Garboli describes sex with ableist terms, such as “blind” and “deaf”, yet he identifies in this mutilation the raison d’être of its autonomy: a being that is offended and triumphant, contracted and expanded, tending towards a final discharge. And again, he portrays a certain voyeuristic attitude, “the emotion that touches us is precisely a frustration, the hunger to witness what we know we are forbidden to see. Sex acts in the dark.” It could be argued that Garboli places these works at the intersection of life and death—Eros and Thanatos—alluding to a psychoanalytical reading of this production. He states that the drawings give shape to that “disturbing theme”, the sexual act, identified as the source of our own biological origin and yet never directly experienced by us, if not in the form of (original) sin— “and there, at that point where there is, perhaps, a celebration of life, there is also, without a doubt, the celebration of the vital, anonymous and exalting presence of nothingness”. Or, and this is the trajectory we wish to engage with, the nocturnal blackness of these drawings and the open poses—the hand that raises the buttocks in a gesture that seems to offer the female genitalia, or swells the penis ready to give itself—become exposed postures that are telling of desires and obsessions in which one can dissolve oneself. Separated by empty spaces, hidden behind columns, the works trace a cartography of cruising, almost as if they were moving on the gravel that covers the floor of the exhibition space—the gravel of middle-class driveways on the outskirts of productive cities, but also the gravel that, in darkness, covers the beaten paths between trees and bushes, while one searches for a fortuitous encounter.

Cruising is used here as a key: it is a methodology for research, production and perception, and a performative practice. Testori wanders among severed busts, open anuses given to passers-by, bodies that have abandoned their subjectivity to become a drive, an erotic offer. Amongst these genitals that have turned into objects—and are thus degenitalised—the artist loses himself. A few months after the closing day of the exhibition at the Galleria del Naviglio, the world of Italian culture was shaken by the news of Pasolini’s tragic death. In an article published on this occasion, Testori confessed his irretrievable loss of unity: he denounced a void in his being homosexual that could in no way be filled, despite his repeated explorations and continuous encounters—like an orifice incapable of finding peace. Not even patience, or the more cardinal virtue of temperance, allow for a truce. The subject, already a mere body, has then no choice but to dissolve in the plurality and polymorphism of his desire, becoming hand, muscle, breast, and finally melting into the cavity of a black sun that allows only fleeting moments of light.

* Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic both the shows are closed until further notice.