Who Talks to Whom?

A review of Giacomo Montanelli’s exhibition ” Who’s Talking to me?”

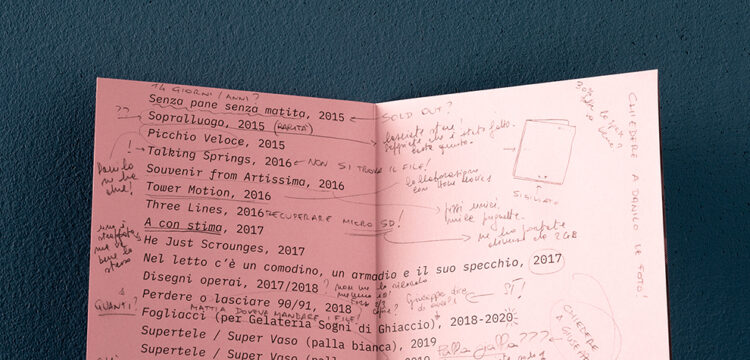

Giacomo Montanelli’s (1996. San Miniato, Italy) solo exhibition at Keteleer Gallery Who’s Talking to Me? consists of a completely new series of paintings that continue with the style and themes Montanelli has been developing for a few years now. Montanelli juggles with our perception. Seemingly trivial computer-generated rudimentary shapes and symbols in complementary colors or greyscale appear to have been selected and thrown together at random. But nothing is farther from the truth. Montanelli likes control and leaves nothing to chance, everything is meticulously thought through.

In his solo exhibition Who’s Talking to me? Giacomo Montanelli presents nine works which, taken as a whole, convey various and almost opposed sensibilities. Each painting is to be encountered as a separate subject, bearer of a different voice and language.

The exhibition’s title precisely wants this point to emerge. The heterogeneous array of selected works is a ploy to illustrate an important aspect of his practice, or rather the freedom and stylistic license that he uses and which allows him to move through various painting grammars and languages.

Montanelli’s aesthetic favors the rigor of geometric forms and flat solid color. References to a well-known artistic tradition are implicit in his work, easy to characterize by appealing to the influence that Russian Constructivism or Dutch Neoplasticism have had on him. Piet Mondriaan and Theo van Doesburg are concrete points of reference in his research. It is also possible to find some comparisons with László Moholy-Nagy’s graphic art. But in the artistic practice of Montanelli, it is also clear that the formal orthodoxy of these artists is disrupted and betrayed; in the use of blotches of color for example, or by the presence of figurative elements such as insects, birds, heads of corn, eyes and, of course, the house—a symbolic element that is part of his personal iconography. Albeit not explicit, here his reference point is Atanasio Soldati, a leading figure of the Italian Concrete Art group.

Even when the composition is made up of only geometric forms, as in Some moment of my life, these elements are shown as floating, almost as if they might want to fall down to the ground; like a series of frames that tell the story of these rectangles. The artist makes a clear reference here to the swiping through of images that has become normal for us, the phenomenon of the infinite scroll that prevails on new virtual platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok.

In the works selected for the exhibition, Montanelli’s research does not speak in unison with the pure cold language of Geometric abstraction. The two-dimensional appearance of the canvas is certainly exacerbated by the flatness of acrylic paint; shapes and images do obey the rigor of the composition, but also lend themselves as disruptive elements. In his reformulation of modernist, abstract and geometric language, elements marking difference are always present. A painting by Montanelli is not simply a painting—or the act of painting which speaks in tautologies with itself.

In the process of subtraction, the artist does not eliminate all of the elements which relate to the narrative and autobiographical structure. His is not a strict “purist” attitude that considers an image exclusively from the point of view of the relationship between forms. As an artist,Montanelli has not withdrawn into the ivory tower of form for form’s sake. This aspect of Montanelli’s poetics is clearly rendered in his use of titles that recall Raymond Carver’s short stories. For Montanelli too, titles offer the possibility of opening up to another vision, indeed, they are used as a meta-narrative tool for the paintings themselves not as a purely descriptive didactic exercise, but rather as an expansion of the multiple semantic possibilities of the work and the many visions that it wants to suggest.

In Social Class, a group of six cute birds that seem to come right out of the world of Warner Bros Cartoon, are perched amusingly along the painting’s diagonals, rendering ironic, perhaps, the inconsistencies to be found in society’s orders and hierarchies.

With the painting, Building one’s own inner landscape is a complex matter, the artist puts into play a layering of symbols and meanings that stretch through the history of art into the contemporary world and go on to touch the personal sphere of intimacy. The landscape depicted responds to the most typical requirements in the genre of landscape painting; it uses a perspective that clearly signals the horizon: there is the sky, the earth, a centrally positioned sun, and a hint at a field of wheat, in a visual memory that carries us automatically to the series of paintings by Vincent Van Gogh on the topic of wheat fields.

The bottom earth-colored strip is used to obscure part of the landscape and stimulate our conscience to reconstruct those missing parts. The mind is incited into a game of hide and seek and, once stimulated, goes beyond the horizon of the canvas. The work seems to make clear reference to research on identity, via suggestive elements tied to the process of identity-making, symbolized by the flag,

On that note, it’s worth quoting from the text by Lauren Wiggers that accompanies the exhibition: “As all flags are meant to represent what a country stands for (often literally referring to its landscape), so does Building one’s own inner landscape is a complex matter that represents the place we inhabit inside ourselves. Out of the bottom beige strip budding ears of corn sprout up, reaching towards what could be a sun composed of a multicolor yin-yang sign, a sort of amalgam of the myriad lgbtqia+ symbols and for Montanelli a symbol for our hyper-complicated modern reality, but set in a primitive, airy landscape. Symbols and flags usually mark those who belong and those who don’t, offering a community to associate with. Today however, the overabundance of things to possibly identify with makes it more confusing than ever to create a somewhat peaceful inner landscape.”

The concept at the foundation of the creation of the flag is the gathering of human variety under a symbol, representative of an ideology and a vision of life. The succession of various flags and of what they have represented throughout history tells the story of both communities forced to accept these symbols and groups that have found their affirmation and self-recognition in those very same flags. Montanelli colonizes the imagination by using and creating a symbol capable of uniting the most universally understandable ideas with private and personal happenings.

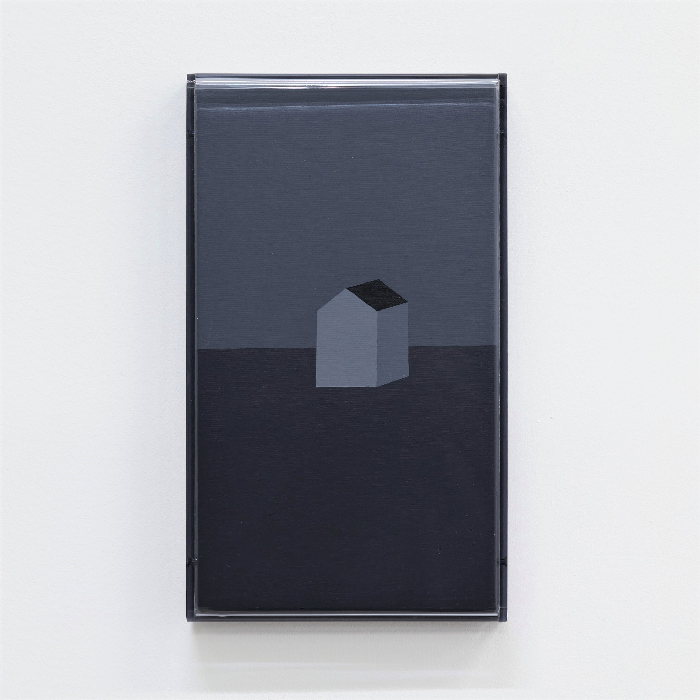

In some of the pieces in the exhibition, such as Fake documentary (spots), When the screen goes off I see my eyes, Have a Mirage 1 and Have a Mirage 2, the use of a plexiglass display case/frame adds a shiny reflective property to the work, the artist has employed for about a year as an additional element to his paintings. With When the screen goes off I see my eyes, we arrive at the extreme of this process of reflection and light refraction, as it entirely obscures the total black image of the painting it replaces the transparent, reflective surface with an image from outside the painting, and as such becomes an object similar to our electronic devices.

There is a significant semantic slip in this work. If we all perceive a black computer screen as a dull object, as signaling its own poor function or its being turned off and silent, here instead the display’s darkness offers the opportunity to experience the very depth of this blackness. It sparks in the observer’s eyes as a search for the quasi-concealed image and form in a game of appearance and disappearance, which in the canvas’ depths refers again and again to the spatiality of its environment, differing each time, depending on the physical place in which the painting is placed.

In this way the artist breaks the two-dimensionality of the work projecting into it the three-dimensional image of reality. “The impact of digital media on our perception plays a huge role in Montanelli’s oeuvre and one could even recognize phone screens in the painting’s dimensions. But art history also has an inescapably huge impact on how we look and what we believe to see. Today, no form, color or symbol is still immune to these kinds of associations. The Have a mirage works beautifully demonstrate this; even a colorless and characterless house in an empty landscape makes the imagination run wild. Hence, what this work really shows is what isn’t shown. Montanelli wants his works to be a reflection of his inner dialogues with contemporary visual culture, the weight of art history on his creative process, the things he reads, everything he wants to be… while also becoming a mirror for everyone to reveal something—however indeterminate—about our humanness.”

Fake documentary (spots) brings to the field a different form of reasoning, via a procedure which, at times, recalls that implemented by Daniel Spoerri in his trap pictures. Montanelli constructs a kind of display case for butterflies, but here—unlike those antiquated and macabre objects that we are used to seeing in museums or in household Wunderkammer, which exhibit insects stuck down with a pin—these butterflies are free to fly from the geometric forms, in a bright blue sky without shadows and to find rest amongst the flower stems. Although apparently painted in a free and uncontrolled manner, reminiscent of the dripping technique, here each spot seems deliberately drawn and to have its own exact place within the work’s narrative.