Where Words Wane

Smell, Memory, and Ros’ Uprooting

“What’s your first recollection of a smell?”*

One of us asked the question—the other paused. It soon became apparent that this kind of inquiry wouldn’t seek clarity, nor would it beg for a quick response. It rather asked for something different: a feeling, an emotion, something embedded in the folds and crevices of the body, long before the mind could summon the adjectives to describe.

The conversations between conceptual and performance artist Lisette Ros and myself began before this question even took shape. But the subject of smell had been seeping into our exchanges from as early as our third call—as if, without our knowing, scent had already begun to insinuate itself into the fabric of the project.

Call III ⧫ 27.07.24 ⧫ GG Rome ~ 16:00 GMT+2 ⧫ LR South Jakarta ~ 21:00 GMT+7

You were in South Jakarta. I was in Rome—6,728 miles apart. I could see you, hear you. We could feel the soft fatigue of blue light pooling into our retinas. And yet, across the screens, we found ourselves drawn to the one sense that had not yet been fully co-opted by the digital age: smell.

“Difficult to pin the earliest, but the strongest from memory is a mix of tobacco smoke and mould, occasionally accompanied by the scent of biscuits and gravy.”

The collaboration between Ros and myself revolved around choosing a shared medium: a book, a film, a documentary, an essay. Our conversations hadn’t started with a fixed concept, but rather as a kind of excavation. A desire to dig and probe into the matter of what made us, “us.” Despite having no shovels at hand, we dug digital holes, dredging through soulseekQt to trawl through strangers’ desktops. Digging became the tool through which we extracted information about the world around us and its relation to ourselves. Like William L. Pope’s Hole Theory, we were guided by the performance, the act itself—not the end result. This article is an extension to this process, something someone will eventually find while digging through the vast amount of information that keeps piling—almost invisibly—onto our screens and across server farms in some derelict part of the world.

Over this year, I began mapping these calls as a series of constellations, each one connecting a medium to one of Ros’ performances, an external text to an internal corporeal process, a theoretical reference point to a lived, felt, and often visceral gesture.

“The smell of my father’s cigarette smoke on skin.”

What became apparent was that the word “smell” appeared in this constellation of notes 99 times. It had emerged from a mutual sensitivity to the sensory, and a shared attention to what often escapes language. Ros’ work operates in that space—where language stumbles and the body picks up the thread. As a performance artist, her practice is grounded in the unheard, the unfelt, the undigested. This includes the bodily processes we often ignore, those sensory imprints that resist our articulation, and the inherited traces we carry without knowing. It is here that we began discussing forms of knowledge and inheritance that are coded within the body, rather than in language itself.

Excavating the First Scent

Before the word, there was the smell.

And no, not metaphorically—but neurologically, evolutionarily, developmentally.

“The smell of moth repellent tablets in my grandma’s wardrobe.”

Smell is the most ancient of senses, in fact, we need to go back 3 billion years, when our planet was in the Archean Eon. Here, prokaryotic microorganisms like bacteria, which harboured around oceanic vents, first engaged in chemosensation—the process of chemical-sensing—the most primitive form of smelling. These simple organisms, without a nose let alone a brain, detected chemical gradients, orienting themselves towards or away from food sources. As cognitive scientist and smell researcher Olofsson puts it “the internal sense of smell was the starting point for the biological evolution that led to humans”—we don’t just descend from LUCA, the Last Universal Common Ancestor, we owe this ancestor our entire development, and still carry the weight of its choices billions of years later. First came smell, then the gut, and only later the brain followed.

Like the bacteria we descend from, before the foetus even develops a nose, its olfactory system is at work. It picks up chemical signals like their mothers’ scent, the smell of the amniotic fluid, or what type of food was ingested that day and prior. By the third trimester, foetuses begin to respond to smells from outside the womb, often the very same ones they will later reach for as adults. The scents of cumin, clove, garlic, peppers, even carrots—all of it enters the body of the foetus through the mother’s diet, the ambient air she breathes, the textures of her internal world.

So, what does it mean, then, that our very first interactions within the world are not visual, not verbal, not even tactile—but olfactory?

Olofsson calls it the “forgotten sense.” In the age of hyper-visualisation, we spend very little time thinking about smell, and smelling. In fact, this sense is completely thwarted by the weight of the image. 6 hours and 40 minutes, the average time people worldwide now spend staring over a screen. If we are born surrounded by smell, we live desperately trying to hide away from it, as if ashamed of our roots. We cover body odour, deploy air fresheners at a whim, and inundate our senses with perfumes—the industry projected to grow at a striking compound annual growth rate of 14%. Fragrances conceal what the body would naturally communicate. They rewrite our story, bypassing the apparent vulgarity of our body’s scent. Yet olfactory judgements are often steeped in historical bias, with odours long wielded to peddle colonialist narratives. But to rewrite, afterall, always means having to erase part of the story out.

So, what exactly might we be repressing? What is it that scent carries, that makes it so urgent to mask, neutralise, or replace? In Revolution in Poetic Language, Julia Kristeva introduces the concept of the semiotic chora—a pre-linguistic realm of rhythms, impulses, and drives. It is the world we inhabit before speech, a world where signification has not yet attached its roots to language itself. A place, rather, where meaning is felt through the body, through movement, through smell. If we consider smell through this lens, it becomes one of the few senses that still bears the trace of this primal register. Smell cannot be neatly organised into grammar. It bypasses the symbolic. It resists explanation. It just erupts, like memories do sometimes.

“A set of smells come to mind, coming back from church every sunday the scent of religious incense wrapped with the smell of spices and cigarette smoke coming from my dad’s second hand car.”

For Kristeva, the semiotic is what the body teaches us before language takes hold: the murmurs of the gut, the lilt of a cry, the rumble of a laugh. This is what she calls “corporeal memory” and smell belongs to this domain, this chora. And it is here too, that Ros’ work is situated. If the semiotic is the modality of signification that precedes language, the chora is its space, a sort of gestational zone, like the womb is to the foetus. It is not by chance, then, that before we had even settled on the topic of smell, right in our first conversation, Ros mentioned Oliver Sacks’ Tourettes documentary. As part of our media exchange-excavation project, I watched this documentary and immediately thought of Kristeva’s semiotic and Ros’ work, especially through the series My Self, which digs into the well-known convention of “just being yourself” (in Dutch “gewoon lekker jezelf zijn”) and what that actually means. In My Self, the (First) Breath, Ros stages inhalation and exhalation as performance—a way to return to the most primal of corporeal gestures, one that precedes speech and ties breath to the very condition of life. Ros uses the body as chora, situating it in different environments and placing it under various degrees of scrutiny—turning the body into a form of petri-dish, a research facility where tactile, olfactive, and the body’s own corporeal chorus come to the fore.

Like the involuntary tics in Oliver Sacks’ accounts of Tourette’s, it is expression without intent, eruption without command. We do not wield smell—it overtakes us. Vision can be averted, sound muffled, speech withheld… but scent is porous. To exist is to emit. To inhale. To breathe out. To be marked by what hovers and clings. Smelling is not looking at the world, but being in it. This embodiedness comes wrapped with ideas of shame, around our origins, our animality, our lack of control. Perhaps we repress smell not because it is weak, but because it reveals far too much—of where we come from, and what we are made of.

The Body as Archive

Every single cell in our body performs chemotaxis, Olofsson poetically reminds us that “our bodies, like those of sea sponges, function thanks to chemical communication between cells. It’s like a symphony of millions of smells and tastes inside our bodies.” As I write, as you read, as we think—billions of cells in our bodies are using ancestral chemosensing to pass information from one cell to the next. Nowadays, we tend to think of information as data, but coded within our very body is an exchange of chemical signals older than thought itself, an almost silent continuous dialogue of smells that predates language. In fact, according to Dr. Pluznick, a researcher focused on the role of olfactory receptors, “we know that olfactory receptors act as sensitive chemical sensors in the nose—that’s how they mediate our sense of smell. But it turns out they also act as sensitive chemical sensors in many other parts of the body.” We don’t just smell with our nose, we do so with the whole body.

“The smell in the air after a summer storm, like rain.”

Smells are not external to us. They live inside us, around us, and between us. This raises the question: does smell belong to the individual? The perfume I choose to wear today will form a cloud of mist around people I don’t know. The cigarette smoke inhaled and exhaled by the mouth of a stranger will touch your skin, the hot vapour droplets depositing on your arm. Your sweat will permeate out of your pores, a waft of it covering the train carriage with its distinct scent. Smell forces us to confront its unruly nature. And in a world where order and control are paramount, the fact we have little say over who smells it, when, and where, leaves us feeling uneasy. But our body is a scented organism. To cover our body odour, to spray perfumes, to disinfect air with artificial freshness—these are all ways of editing the archive. Olfactory historian and curator Caro Verbeek calls smell a “time capsule,” a sensory archive capable of collapsing temporal distance. A single inhalation can summon decades, centuries, and exhume ancestral history into the present, whether we like it or not.

When we think of archives, we usually summon images of books, papers, registers, databases. But our body conceals within it the more volatile form of the archive: smell. Unlike written records, olfactory memory resists categorisation, it does not sit neatly in boxes, folders, or shelves. Which means that if we want to dig up the past, we need to follow our nose. And that’s what artist Lisette Ros followed: a trail of scent that marked her body before she was even born, dragging her back to Java. As part of Ros’ ongoing My Self series, the scent trail traces her lineage back to Indonesia, part of the former Dutch East Indies, where her grandfather was born in 1916. It is here that the next chapter of the series unfolds, My Self, the (Unfamiliar) Roots, a research into a silent inheritance passed down from her grandfather, who was taken from Java at the age of ten. His life, like many others, was shaped by what the Dutch-Indo community calls Indisch (Ver)zwijgen—the intergenerational silence around displacement, colonial rupture, and erasure.

“Grandpa’s pipe, and also his shaving foam—old school, with a brush.”

Photographs, national records, videos and even audio files—none of this media could truly answer Ros’ questions around her grandfather’s displacement from Indonesia to the Netherlands. Nor could they answer the effect this had had on her body. What had been passed down? What habits, traditions, rhythms, or gestures had survived the relocation and had been carried down from her grandfather, through her mother, and right down to her own body?

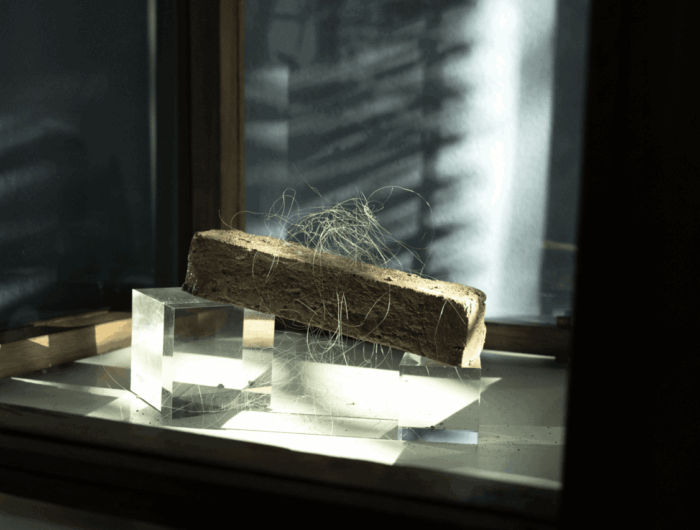

Ros approaches this silence not by trying to fill it solely with words, but by working with what exceeds them: the body, its motion, involuntary rhythms, and scents. If smell is indeed a time capsule, as Verbeek suggests, then My Self, the (Unfamiliar) Roots enacts the opening of that portal. It is less about recovering an intact or even chronological narrative, than it is about releasing what lingers within: the smell of the Javanese soil unearthed with her own two hands, the earth lodging beneath her fingernails and the damp wetness of the air’s moisture sweating through her clothes. The aroma of kreteks mixed with garlic, nutmeg, and beef seeping out of slow braised semur pots. The scent of petrichor and sulphur rising through the air in Bandung. The smell of petrol, palm sugar factories, and burning coal smoke.

At the heart of Ros’ practice is not the journalling of ancestral memory, but the act of reliving and re-enacting our ancestry through the encoded memory within our bodies. Ros’ work reminds us that this archive is not somewhere else, it’s not in a dusty attic or well-organised historical archive—it is, and always has been, right here, in our body. The smell of soil clinging to the roots, of humidity in the air, of sweat on skin—all of it became a record, an archive not bound to paper or screen but to the air we breathe. In this gesture, Ros revealed that what we inherit is not only genetic material but atmospheres, materials, and sensations—that ancestry itself may be inhaled.

Uprooting Our Scent Trail

“The smell of burnt caramel coming from an iron pot simmering on the stove, along with the knowledge that I had done something wrong.”

Caro Verbeek, in a lecture entitled Inhaling Heritage tells us smell is an “almost intangible trace, a few molecules entering our nostrils, an echo of what happened in the recent and even most distant past.” Working off this indissoluble link between memory and smell, Verbeek asks us to revisit our own past, as well as historical events, from an olfactory, rather than visual or textual perspective. If we could go up to a painting and smell it, how would our perception of it change—would we remember it more vividly? Would we relate to it in a more personal way? In a passage from The Origin of the Work of Art, Heidegger asks us to look at Van Gogh’s painting A Pair of Shoes. He invites us to look beyond the representation of a pair of worn out boots, in order to understand the true meaning, the truth, concealed behind those brush strokes. By looking beyond the formal qualities of the painting, we access the hidden layer between the paint and the world: that of hardship, of laboured sweat and calloused fingers, of the damp soil and harvested fields those boots walked over. For Heidegger, a painting is never merely an object to contemplate, but an event to be experienced. Caro Verbeek picks up this very thread, following his trail of thought yet carrying it further—drawing us inward through the nose and outward again into the world. Heidegger’s insistence that art is not representation but a happening of truth opens the possibility that olfactory traces, too, could participate in this unconcealment. It is precisely this path that Verbeek, as historian and curator, and Ros, as performance artist, each pursue in their own way. In Verbeek’s case, this means recreating the odours of historical paintings to bring the scene to life; in Ros’, it often involves crafting olfactory materials from her own body—sweat, saliva, hair—each bringing the presence of lived experience to the shared performance space.

In Ros’ quest to trace (unfamiliar) roots through ancestral memory, and to reawaken what the body recalls when immersed in the smells, textures, and atmospheres of history—her performance practice first turned inward, with the inhale of the My Self series, and then outward, as an exhale, in its next iteration, via “(the Act of)” sequence.

To uproot is to disturb what lies beneath, it’s the act of releasing into the present what had previously been buried. In Ros’ performance art work, the act became an exhalation of history: smells, textures and energies released from the ground joined those from the body, coalescing into a cloud of rediscovered truths and knowledges. Here, Ros’ body did not represent memory, it transmitted it. Smell worked as a carrier, a vehicle of what was otherwise unutterable. We often think of memory as a narrative we tell ourselves, but perhaps it is more accurately a trail of molecules waiting to be stirred, reactivated, breathed back in. Smelling is, at its most basic, breathing. The olfactory organ is inseparable from the respiratory one: to draw air into the lungs is also to draw particles into the nose, whether we want to or not. Some cultures collapse the two entirely; in Sanskrit, prana refers both to breath and to life force; in Hebrew, ruach is spirit, wind, and breath all merged into one.

“Tobacco from my father’s, your grandpa’s pipe.”

To live is to breathe, to breathe is to smell. Ros’ work presses this point: uprooting is not only movement through soil, but a choreography of breathing—lungs filled with dust, earth, the faint scent of ancestral roots exposed to light. It is less about individual perception and more about participation in a shared space, a communal chora. Which takes us to the second iteration, (the Act of) Smell-ing, including a shared and participatory performance element where it is not just the smell of the land that is brought to the fore, but the individual odour print of each participant too. In this collective inquiry into the odours we carry and those we choose to repress, Ros gathers the unperfumed shirts worn by participants over a minimum of twenty-four hours, while subjecting herself to the same discipline for 172 hours: refraining from showering, bathing, and using artificial scents, or detergents. In doing so, Ros tries to influence her body to return to a natural odour print state, a state she admits she probably hasn’t encountered since birth.

The body-as-archive, then, is not metaphorical, it’s actual. Smells are stored in soil, in skin, in the very cells that make up our body. They travel through breath, through air, through our mouths and into the smallest of cells. They erupt in Ros’ performances, demanding that we acknowledge the ancestral knowledge we carry, even when it lies buried, unspoken, unnamed. To uproot is to remember. To inhale is to inherit.

Call XI ⧫ 25.08.25 ⧫ GG London ~ 15:00 GMT ⧫ LR Yogyakarta ~ 21:00 GMT+7

A year on, and you’re in Yogyakarta, while I’m writing from London. It’s the end of summer and in England the air still feels heavy with humidity, the sash window wide open, the smell of sun-cooked leaves now punctured orange, some fall off their branches and onto the tarmac. The rain will soon wash them away.

“Not an easy one, but I would say the first memory I can think of is the smell of freshly cut grass and the aroma of each season approaching.”

In the end, what Ros is attempting through performance is not to explain smell, nor to capture it within the limits of language, but to stage its force: as archive, as inheritance, as eruption. Her work reminds us that smell is not an accessory sense but a medium through which history breathes, carrying ancestral memory into the present moment. By uprooting, by inhaling, by exhaling, Ros performs what words cannot: she makes the body itself the chora where memory and knowledge resurface, fleeting yet strongly bound to our memory. Where words wane, performance begins—and smell, that most porous of senses, becomes both material and method for reimagining how the past lives on within and around us.

“It is still difficult to pin the earliest…”

*The answers to the question “What’s your first recollection of a smell?” came from Ros’ and Gasparini’s family and friends.