What You Hear is What You Get

On Carolyn Lazard’s practice and labor, biopolitics, physical impairment and disability

[Image description: a set of hands sort seven pillbox compartments on an embroidered tablecloth. The image is taken from an overhead position with the hands partially obstructing the view of the differently colored compartments. The compartments are yellow, blue, pink, green, and white. They are filled with differently colored pills too. Bright orange pills are held in the palm of one hand.]

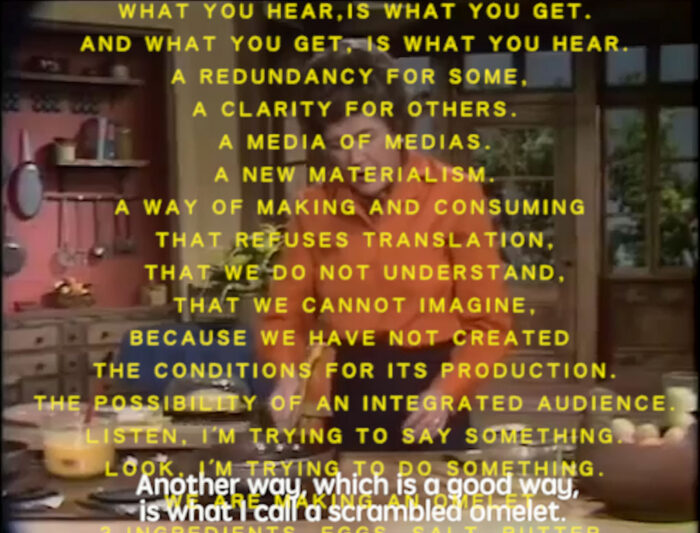

The year 1972 saw the first use of open captions—text burned into the image—for deaf and hard of hearing audiences on U.S. television, doing so with the cooking show The French Chef starring Julia Child. Carolyn Lazard’s video A Recipe for Disaster, currently on display at the Kunstverein München as part of the series Schaufenster, draws on footage from the popular TV broadcast and constitutes a critical study of the accessibility and barriers imposed by mass media.

The French Chef was a television cooking show broadcasted from 1963 to 1973, produced by WGBH, Boston’s public TV network, US. In each episode of the ten seasons, Julia Child, an eccentric TV personality with a great presence on stage, was meant to teach American housewives the marvels of the cuisine française, on how that was actually within the reach of all, neither too expensive nor too difficult and very adaptable to domestic daily life. At the end of each episode Julia Child used to greet the audience with a Bon Appetit! a greeting that became the show’s trademark.

Carolyn Lazard’s work A Recipe for a Disaster (2018), is based on one of the episodes of the American series. Before diving into the artist’s practice, I thought this was meant as some sort of a provocation, a pop and irreverent reading toward the arrogant exploitation of the food industry and its cultural consumption as one among last decades’ fads, in an infinite production of generalist entertainment, along with in-depth tv programmes, talent shows, books, magazines and movies, in addition to entire tv networks completely dedicated to the universe of food and cooking. Probably, the forceful exposure to this mass-produced universe is what has conditioned my (ableist) gaze at first.

[Image description: Julia Child holds a pan over a stove in a rustic pink and beige kitchen. She is a white woman with short curly brown hair. She wears an orange button down shirt with a black apron. On the counter is a bowl of eggs and a glass container of whisked eggs. Behind her is a wall of kitchen utensils. Behind her is also a doorway leading into a courtyard with plants. On top of this image, aligned to the center of the frame is a block of yellow, sans serif text. It reads, “WHAT YOU HEAR, IS WHAT YOU GET./AND WHAT YOU GET, IS WHAT YOU HEAR./A REDUNDANCY FOR SOME./A CLARITY FOR OTHERS./A MEDIA OF MEDIAS./A NEW MATERIALISM./A WAY OF MAKING AND CONSUMING/THAT REFUSES TRANSLATION./THAT WE CANNOT IMAGINE,/BECAUSE WE HAVE NOT CREATED/THE CONDITIONS FOR ITS PRODUCTION./THE POSSIBILITY OF AN INTEGRATED AUDIENCE./LISTEN, I’M TRYING TO STAY SOMETHING./LOOK, I’M TRYING TO DO SOMETHING./WE ARE MAKING AN OMELET.” Layered on top of this text is a white subtitle at the bottom of the frame that reads, “Another way, which is a good way, is what I call a scrambled omelet.”]

Instead, the 27 minutes video A Recipe for a Disaster reproduces in loop the episode of The French Chef where Julia Child cooks a scrambled omelet, but the artist’s choice is not as casual. Broadcasted in 1972 on WGBH, the episode is a replica of an episode from 1963, and it was one of the first in the world to include real-time captioning for deaf and hard-of-hearing audiences. In fact, Boston’s WGBH network became the first outlet in history to adopt this system of subtitles within his shows embedded in the image, independently from the audience’s choice.

Lazard’s version A Recipe for a Disaster reports the original captioning of 1972, with a transcription of Julia Child’s monologue at the bottom centre of the screen, with white colored small letters. The artist has also intervened on the video by juxtaposing their own recorded voice describing the actions made by the tv host throughout the episode, to make it accessible also for the blind and visually impaired audiences. Finally, a text flows on the screen in yellow capital letters, written by the artist and read out loud, stating:

WHAT YOU HEAR, IS WHAT YOU GET. / AND WHAT YOU GET, IS WHAT YOU HEAR. / A REDUNDANCY FOR SOME. / A CLARITY FOR OTHERS. / A MEDIA OF MEDIAS. / A NEW MATERIALISM. / A WAY OF MAKING AND CONSUMING / THAT REFUSES TRANSLATION. / THAT WE CANNOT IMAGINE, / BECAUSE WE HAVE NOT CREATED / THE CONDITIONS FOR ITS PRODUCTION. / THE POSSIBILITY OF AN INTEGRATED AUDIENCE. / LISTEN, I’M TRYING TO SAY SOMETHING. / LOOK, I’M TRYING TO DO SOMETHING. / WE ARE MAKING AN OMELET.

As the three ingredients (eggs, salt and butter) to cook an omelet following the original French recipe, the piece works on three levels: image, sound and text. Almost as obvious as Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs from 1965, despite the aim being deeply diverse: what Carolyn Lazard does is to give voice to a direct and conscious criticism of accessibility and barriers imposed by the mass media, on the way it structures communication and information exchange in today’s social system. Our usual way of producing and consuming rejects this translation. No condition is currently created for any inclusive and integrated fruition. The emphasis is centered around the necessity towards a larger accessibility to information, indeed, but also to the tissue and the mechanisms of our political, social and cultural system, not as a mere “generously granted” supplement in society but rather as a fundamental principle of the social structure itself.

As Lazard writes in How to Be a Person in the Age of Autoimmunity “health and wellness become an ideological tool deployed to normalize the body in the interests of capitalist production.” Indeed, in our society sickness is considered as a temporary condition—in most cases “abnormal”, out of the ordinary. Sickness does not fall within the norm. A norm that is based and built on a linear and progressive view, without any space for defection. The very same norm that declines the meaning of health in terms of productivity and within its realm, often according to duration and work-load capacity.

As Michael Foucault would put it, capitalism is, above all, a system of power founded on a specific perspective, both epistemological and political, according to which mind and body are separated: the mind can find different ways to objectify the body, to exploit it and bend it to a best-performance standard, thus to silence it when it occasionally tries to rise against any “inhuman” practice.

The artist started to experience sickness as a chronic and incurable condition when they were about twenty years old, when they were diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and Ankylosing Spondylitis, both autoimmune diseases. When Lazard tells their experience, they tell the story through the many crises they had to endure, along with the exhausting process of dealing with a particular condition, both existentially and physically alienating. Two, in particular, are the texts that speak about their personal experience without any filter: How to Be a Person in the Age of Autoimmunity (2013), and The World Is Unknown (2019).

In How to Be a Person in the Age of Autoimmunity, they notice how even the attempt to communicate becomes hard, because of the lack of terms we have to describe physical diseases. To express our pain and sorrow we must use metaphors; and, in any case, in the common imaginary, sickness is thus linked with feelings of shame and blame, and characterized by an unexplainable moral connotation that people prefer to deny or silence. “Expectedly, I developed feelings of guilt over my inability to be a productive member of society: moralizing my disability as sloth, viewing my body’s natural limitations as personal failure.”

Deeply rooted within our way of thinking, however, this perspective seems to be reductive, sharply contrasting health and sickness, as two necessary and opposite categories, tertium non datur.

[Image description: a hand extends over seven pillbox compartments on an embroidered tablecloth. The image is taken from an overhead position with the hand partially obstructing the view of the differently colored compartments. The fingernails are painted gold. The compartments are yellow, blue, pink, green, and white. They are filled with differently colored pills too. There is a patch of bright sunlight on the tablecloth and there are a few pill bottles visible along the edge of the frame.]

Those sounds reductive and meaningless particularly towards those who must keep up with some chronic conditions or dysfunctions, health states and conditions, either physical or psychological, congenital or acquired; the “disability” that comes along structurally becomes a trigger for exclusion. Or in Lazard’s words:

“The social model of disability maintains a clear distinction between disability and impairment. Impairment is an illness, injury, or congenital condition that causes loss of ability or partial ability to function. Disability, in contrast, signifies a particular relationship to one’s environment. Disability is the reflection of barriers that prevent people with impairments from participating in society. For example, when I have difficulty walking, it is a physical impairment. I am disabled not by my physical impairment, but by the fact that many buildings don’t have ramps or elevators. Capitalism is an economic system that assesses bodies in terms of labor power, designating certain bodies as useful and others as not. Physical or mental impairment as an excuse for exclusion from social or economic life is endlessly reinforced under this system.”

In both writings, an interpretation of the pathology as a sort of liminal situation emerges from Lazard’s words, in that specific occurence that brought them to experience the concepts of body and time differently—very differently from the capitalistic society’s impositions. “While I was sick, my time was not economically exploitable in the Marxist sense. I could not contribute to the workforce. What happens when time is not money? I spent a whole year mostly lying in a bed producing nothing; extremely bored. Maintaining remission and taking care of myself required a lot of my time. In order to justify my unemployment, I still thought in capitalist time designations, and would tell people that taking care of myself was a ‘fulltime job’.”

However, living with pain and having to deal with a completely new way of life, they managed to eradicate, step by step, both the logic of time-as-work and of productivity-as-duty. In Crip Time, a video realized in 2018, the temporal dimension is shown according to this acquired sensibility, through its lyrical and morbid nuances.

[Image description: a set of hands sort seven pillbox compartments on an embroidered tablecloth. The image is taken from an overhead position with the hand partially obstructing the view of the differently colored compartments. The compartments are yellow, blue, pink, green, and white. They are filled with differently colored pills too. There is a patch of bright sunlight on the tablecloth and there are a few pill bottles barely visible along the edge of the frame. Deep red pills are held in the palm of one hand.]

The ten minutes video displays the hands of the artist, with golden nail-polish, intent to administer a bunch of therapeutic pills that Lazard must take, in seven boxes of different colors, each box meant for a single day of the week, each box split in four diverse compartments (morning, evening, bed time and noon).

The pills are enormous and colorful. The labels on the little boxes, written with a black marker, appear partially erased by the frequent use. A ray of sun shines on the table, covered by a nice white blanket, embroidered with flowers. The artist’s gestures are methodic, automatic and precise. Time is rhythmic and repetitive.

In opposition to a progressive and utilitarian logic, time is here represented as something thick and messy, as a duration whose complexity—and most of all whose fatigue is almost physically perceivable. In Crip Time, time becomes a sort of ritual, a tool which is also a resource for the future, even though the future has now become impossible to forecast, and for this reason, it appears frightening.

Even the body is characterized, according to the artist, by the same asset of indetermination. In The World Is Unknown they write “while biomedicine reads the body like a text, there is something about possession that matches the illegibility of the body—its sensuousness, its reach beyond words and our own understanding. I don’t mean to suggest that the body is illegible so let it be poked and prodded until it releases some information. I am saying that we need a medicine that emerges from this sensuousness, a medicine that feels in a different language, maybe the language of dreams.”

In opposition to the positivist conception of biomedicine, which is reductive precisely because it is dogmatic, in a conception keen on reading the body as a sort of machine that has to realize the best possible performance, Lazard embraces a holistic view, according to which the mind is constituent of the body. The artist underlines the importance of feeling and experiencing, rather than testing; they point out the need of being aware of our body according to new possibilities and unedited tools.

“I’ve come to understand that the enemy of health is neither pharmaceuticals nor snake oil, but dogma. The body is too unwieldy to fit within any totalizing discourse. Sometimes my body is transparent, exemplary of karma, of action and reaction. Sometimes it is a solid mass of impenetrable, unknowable matter. Whatever it is, I am my body as much as it completely evades me.”

The complexity of Carolyn Lazard’s thinking in respect to the way we conceive body, time, illness and disabilities totally disrupts the limiting ease of the reductive duality of health and sickness,which regulates our political, economic and cultural dynamics. Against a conception of accessibility promoted by the capitalistic system, which advocates for coherence, rationality, intelligibility and transparency as thriving principles, the artist proposes instead a whole new definition for the term, one that emphasizes values such as collectivity, care and relation. Returning to A Recipe for a Disaster, accessibility can’t be considered a mere supplement. It must become a fundamental principle within our social structure.

Lazard’s artworks help me remember that the existential personal dimension is never separated from the collective political one. Their art comes from a perspective of the world able to look at the particular in a way that is both coherent and concrete. Within the deep need to deconstruct a big chunk of what we’ve been told to be our past social heritage, their voice is a valuable witness of this system’s fallacies.

Maybe, the intrinsic rituality of art-making turns into a tool against this capitalist conception of time. Maybe art is indeed one of the ways we’ve got to distinguish time from work, and a viable resource to oppose it. Actually, what can we do?

As the artist affirms sarcastically and sharply in A Recipe for a Disaster, through the yellow text that flows in loop on the display read by an aseptic voice as if it were some sort of mantra:

LISTEN, I’M TRYING TO SAY SOMETHING.

LOOK, I’M TRYING TO DO SOMETHING.

WE ARE MAKING AN OMELET.