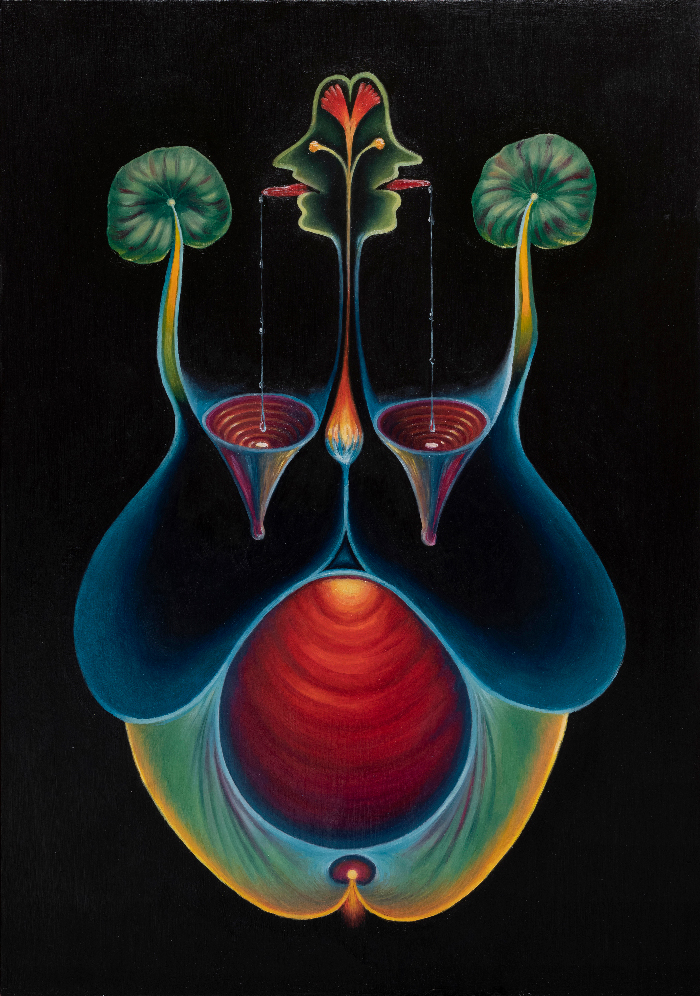

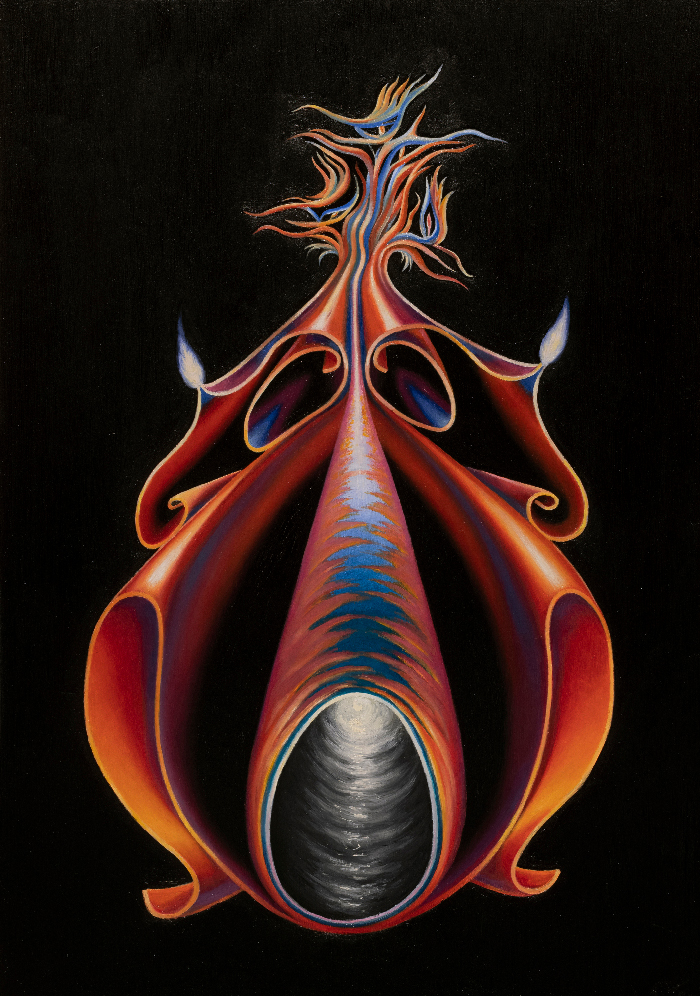

Venuses

Cleo Fariselli on motherhood, pregnancy and labor

Veneri is an exhibition by Cleo Fariselli, and a public programme of readings and talks presented by ALMANAC in collaboration with OGR.

The exhibition presents a new series of oil paintings conceived by Cleo Fariselli during her recent pregnancy. Childbirth and motherhood, the starting points of these works, are seen as transformative experiences not only on a bodily and personal level, but also conceptually and philosophically. Fariselli explored this experience under a different light, investigating the emancipatory and positive aspects in contrast with the narrative we are used to which confers a passive and sacrificial aura to women.

The project is realized in partnership between ALMANAC, OGR, Associazione Casa Maternità Prima Luce, and supported by Fondazione CRT, Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo and Giovanni Battista Mossetto Onlus.

Prehistoric Venus figurines are among the most stimulating and fertile topics of debate in the archaeological field. Over the years countless theories and interpretations have attempted to give an explanation to these enigmatic and fascinating figures. Among the most welcomed theories we find the one that sees the figurines as representations of divine female entities: the archetype of the creative and fertile woman, in touch with lunar cycles and natural forces. Another theory speculates that these figures are an attempt at self-representation by women who, lacking mirrors, portrayed their bodies crushed by perspective distortion.

When I was pregnant there was a moment when I felt the need to stop and listen to myself, to tune into what I was experiencing on a deeper level. My Venus figures came forth at that pivotal moment. There are twenty-one of them in total. I made them all during the third trimester of pregnancy, to support myself in my current state but also in preparation for the birth, which I chose to do at home, in their presence.

My daughter Teti was born 16 months ago. It was my first pregnancy and it changed my life. I came to this experience with no preparation other than a jumble of stereotypes and misconceptions about the subject. My notions about gestation and childbirth were a cocktail of movie scenes, images from art history, medical notions, advertising images and stories intercepted here and there from relatives, friends and acquaintances.

Already since the first few months I began to feel a growing discomfort with the baggage of imagery I was carrying around. I felt great transformations were taking place, both physical and psychological, and the pre-packaged images that my mind was trying to draw on to help me in the process of understanding what I was experiencing, really did not apply to the experience itself. Around me, neither the medical nor the media world was very helpful in supporting me in this quest for meaning. In the personal experiences of friends, relatives, and acquaintances, I was struggling to find my own space. I yearned for a context that gave me the information I needed to navigate the jungle of exams and preparations I had ahead, but at the same time, that would not become overwhelming, allowing me to experience these transformations in a way that was respectful of my own time and manner, allowing me to construct an imaginary that reflected myself. I found this dimension when I met a network of women, midwives and perinatal educators, who informed me without indoctrinating or frightening me, helping me to trust myself and the journey I had embarked on.

The reassurance aspect was crucial, because pregnancy and childbirth naturally bring along a certain amount of fear that, if fomented, can become paralyzing, obscuring the perception of the positive and deeply empowering aspects of these experiences. Those who take advantage of the vulnerable state of pregnant people by frightening them with terrifying scenarios and overly intrusive directions bear a great deal of responsibility for depriving them of the opportunity to feel like protagonists in one of the most powerful and transformative phases of their lives. The line between authority and authoritarianism on the part of those, professional and not, who arrogate to themselves the right to impart advice and prescriptions can sometimes be very blurred.

When I was pregnant, my fear took the form of a sort of claustrophobia: I felt as if I were aboard of a plane or a ship, taking off or raising anchor for a long journey that, even though much desired, had begun without warning and once departed it could not be interrupted before time, except due to some dramatic fatality. As in a journey, once you set out—willing or not—you have to let yourself be carried along and try to enjoy it, knowing that on arrival you will be transformed, or at any rate in a very different place from the one you left behind. Moreover, the last stop of this journey would coincide with childbirth, which is the experience universally recognized as one of the most intense, painful and unpredictable one can experience.

Beyond reassurance from the outside, I felt a pressing need to find my own tools to cope with this fear. My primary instinct was to slow down and stop. In silence, slowness and stasis, I could relativize the fear, clearly sensing that it was not the only force at play. Its voice was perhaps the loudest, but in the background murmured a far more complex, articulate and powerful chorus, composed of many other voices and sounds, human and non-human, sometimes in agreement, sometimes in disagreement. A massive, constantly moving creative flow like a great river heading toward an inexorable leap of a waterfall, which in that case was represented by childbirth.

I have only one daughter, but those who have had more say that each gestation is a new experience, a journey always different, as unique and unrepeatable as the creature one carries. In these infinite diversities, however, expectant mothers share for those nine months a common psychophysical world, in touch with submerged and ancestral forces. Powerful and impersonal energies that connect those who are expecting like an underground network of rivers. Mysterious and primordial landscapes, familiar and alien at the same time, from which we are brushed, lapped, swallowed… and with which we ourselves slowly learn to become familiar, though without ever fully knowing them.

Tuning in to gestation is not something to be taken for granted. Or at least for me it wasn’t. As with other natural phenomena (of a non-cataclysmic nature) one can pause in contemplation, listen, letting oneself be carried, or of finding your own way, even thinking about something else. The difference is that the phenomenon of pregnancy takes place within the confines of our bodies, and whether we want it or not, whether we like it or not, whether we think about it or not, pregnancy proceeds, moves us, changes us, demolishes us and builds us up, and all of this happens by itself, quite independently from our reason and will. The fact that we stop and listen is a choice, just as we would do in front of a sunset or an eclipse. The only difference is the degree of psychophysical preparation with which we will arrive at the last stage, which in the case of pregnancy is childbirth. And during childbirth thinking about anything else is impossible. Childbirth is overwhelming, it is pure presence, it is animal here and now, it is a volcanic eruption in the waters of the sea.

Between the second and third trimesters, in my quest for slowness, for listening, and for immersing myself in myself, and for creating an imagery of reference that would stick with me, I rediscovered drawing. I felt the need for something that would help me connect and at the same time allow me to note down the feelings and visions I was experiencing. I was trying to understand myself, to explore that I was no longer alone, a feeling of being a place, a nest, a landscape, an animal, a boiling forge… so like that I started drawing the very first figures, using simply a pencil and a white sheet of paper. As the graphite flowed across the paper, with half-closed eyes I tried to tune in to how I felt. The result were some rather ungraceful figures, with small heads, large bellies, protruding breasts, and almost nonexistent hands and feet. The parallels with prehistoric Venus sculptures were inevitable. So I went to look at them again, and I began to perceive them in a new light: they seemed to speak to me and I wanted to keep one with me, not as a relic but as a tool. To hold it in my hand, in my pocket, or near me, like a talisman. It seemed to me that a woman before me, long before me, having gone through the journey of pregnancy, or more likely many more than one, had stopped and decided, more or less as I was doing, to fix in a form her body as a pregnant woman or in general her body, capable of these extraordinary changes; to keep it with her, as a small trophy, a simulacrum of what the body can do, of what we can do, and to show it to others, perhaps young or primiparous, to communicate to them:

“Your body has changed, is changing, will change. The balances are different, and constantly changing. Slow down, stop.

Sometimes the belly is in charge.

The belly goes on by itself.

The belly knows what it is doing. You have to trust it.

You have to trust yourself. You are strong, you are divine strength. Don’t be afraid.”

A reassurance. A reminder. An invitation to self-confidence in connection with the world. I am a woman but I am also a rock. I am a woman but I am also a forest, a river, a gear, a beast, an ocean, burning lava.

Ina May Gaskin is a legendary midwife who, since the 1970s in the United States, has helped hundreds (perhaps thousands?) of women to give birth, providing information for more conscious and active gestation and childbirth, and reviving the culture of home birth. In her book, Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth, I was very impressed by those stories in which during key moments of labor the midwives or other women who assisted, offered images, figures to the women in labor to look at. A blooming flower. A figurine depicting a woman with an opened vagina and a smile on her lips. I was reminded of the Sheela-Na-Gig, the medieval figurines common on capitals and decorations of churches, castles and other architecture, depicting figures holding open their giant vulvas with their hands, smiling serenely. They also seem to be saying “you can open yourself, you can do it, don’t be afraid, trust the possibilities of your body, it’s meant to be this way.” Ina May Gaskin’s approach to childbirth is described as “natural, old-age-inspired and fearless.” Keeping fear at bay is the central element as in all rites of passage.

Accepting the presence of pain is not the only challenge in childbirth, surprisingly because there is more to childbirth than pain. The great unspoken, the great taboo, and the unsettling, scabrous, mind-blowing discovery, to be whispered to friends who look at you incredulously with squinted eyes, is that in childbirth there is also pleasure. The vagina is not just another orifice, and childbirth is part of the spectrum of the female body’s sexual potential. The vagina opens when there is love, when there is contact and sensuality, when there is trust. Childbirth, with its hormonal rushes and rhythmic pacing, predisposes all of that: to a colossal, erotic, stormy, overwhelming love experience. It also takes courage to accept pleasure where we never thought we would find it. I believe it takes some anger and revolt, toward a cultural and social narrative that still depicts the pregnant woman and the parturient as passive, weak, martyrs of sacrifice rather than as active and powerful subjects, protagonists of an exceptional creative process.

The profoundly empowering nature of pregnancy, childbirth, and motherhood were a discovery that I would have never imagined before experiencing it firsthand. Nothing in the mainstream narrative would have made me think that I would feel this way at that time of my life. That shocked me, but it also made me upset. What would have happened if I had not come across the right people? What would have happened if I had settled for the routine path, without informing myself and digging deeper? What would have happened if pregnancy instead of this time in my life had found me younger and inexperienced, and more easily influenced? All pregnancies and all births are different: slow, fast, easy, difficult, smooth or full of obstacles. On this journey I realized that the role of the pregnant woman’s awareness and that of those who accompany her is substantial and can be the discriminating element between one of the most positive or traumatic experiences of someone’s life.

For me, images have been important. I like to think they fit into a line that began with Venus figurines tens of thousands of years ago. Making these figures public was not a decision taken lightly, because they have been very intimate companions for me, and a part of me wanted, and still wants, to protect them. If I have done so, it is because I hope that other people can find inspiration, strength and reassurance in them, wishing them all to experience the transformations of their bodies as openly, receptively and fearlessly as possible.