Unabashed Celebrity Worship

Or the artist as a commodity or the new economy of presence

The following excerpt is part of a larger research on the language of the cultural industry, Contemporary Art, pseudo-critique, thus on the crisis of that very same language. Deeply entangled with the capitalist system of celebrity worship, the economy of presence is one of the paradigm and symptoms of this crisis, within a structure where the market frames and dictates the production modalities of the artwork—and when the artist becomes a commodity, of the artist themselves.

The commodification of art and the use of quantitative market methods to determine value judgements and establish the success of a work of art, have legitimized positions such as Warhol’s, who, in his The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, fully grasped the process of commodification to which the artist himself was subject: “Some company recently was interested in buying my aura. They didn’t want my product. They kept saying, We want your aura. I never figured out what they wanted. But they were willing to pay a lot for it. So then I thought that if somebody was willing to pay that much for it, I should try to figure out what it is.” In the manifestations of art, the artist’s life and presence on the social scene become increasingly important vehicles for declaring the success of a work: “Artists—wrote Rosenblum—must sell their image, through the staging of their own particular sensibility and other forms of idiosyncratic behavior as well as relying on the actual artistic qualities of their work (…) in this process, they create and enter into a game that has a profound alienating effect on themselves.”

The focus is no longer on artistic production, but on the individual, crowned by the market as a winner, and their lifestyle, achieved through the production of a brand that conforms to the stylistic clichés that has led them to success. It is a synchronous movement, a virtuous circle that feeds itself and contributes to the same goal: the creation of a new popular myth that, in turn, will nourish an increasingly larger market. Media attention increases the propensity of the new enthusiasts to “loyalize themselves to the world of art, and this devoted interest augments the involvement of the media. Meanwhile the price value, the abstract equivalent of any judgement, is spread over the entire influential and enticing movement: money as a measure of value itself. The transformation of art into merchandise itself provides the perfect and unquestionable yardstick of judgement: the battle of ideas becomes a struggle for success, and few realize that this is not an equivalence.”

In economic terms, the presence of the artist appears as a strategic investment to impose an artistic model. The term “presence” refers to the idea of a “hic et nunc” and bodily interaction. However, the strengthening of the telecommunications industry and the diffusion of information under the dictates of the global economy requires a radical redefinition. Technology, increasingly refining its technique, is used in the economic system in order to facilitate the simple and immediate circulation of opinions and information. Social, economic and cultural relations do not hinge exclusively on the direct encounter between individuals, but on the production, reproduction and preservation of information.

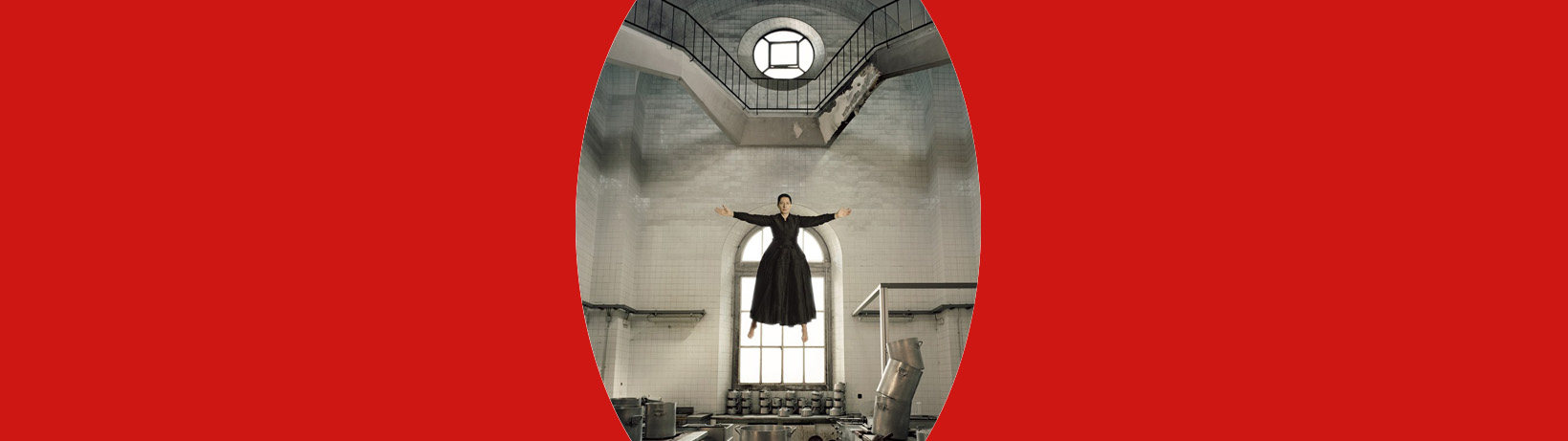

“Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present,” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, through May 31, 2010. Opening preview: March 9, 2010. Photo Andrew Russeth.

It is within this framework that the individual constantly assesses to what extent and in what gradation to be “present”. William J. Mitchell describes economic dynamics in the light of what he calls a “new economy of presence”, whose goods are “time”, “movement” and “attention”. He proposes an evaluation grid concerning “costs”, “advantages” and “disadvantages” of presence, in which the face-to-face experience remains the most effective and understood, even if expensive: “Face to face provides the most intense, high-quality, potentially enjoyable interaction. It is not constrained by storage capacity, telecommunications bandwidth, or interface limitations. But it is also by far the most expensive option, both in direct cost and opportunity cost; it requires travel, and it consumes real estate, often in expensive, central locations. Most importantly, it consumes your attention; you only have a limited amount of time available in your day for meeting people, and it demands some of this. So it makes sense in contexts where the importance of the interaction justifies the high cost.”

The monetization of presence is a logic increasingly dear to contemporary art and its institutions. The art market itself revolves around a series of events that appear to be unique and unrepeatable. Just think of the countless trade fairs in the sector, art weeks etc. “Besides producing works,” writes the artist Hito Steyerl in her book Duty Free Art, “today’s artists, or more generally content providers, have to devote themselves to many accessory services that seem to become the most important aspect of their work: the moment of the questions is more important than the projection, the live reading is more important than the text, the encounter with the artist is more significant than the one with the work; not to mention the proliferation of para-academic and social media formats that multiply the ways in which a non-alienating presence to the public is hoped to be delivered.”

In this sense, the retrospective Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present, hosted by MoMA in New York in 2010, assumed a paradigmatic value. Abramović writes in the exhibition catalogue: “I really like the moment when the performance becomes life in its own right. In The Artist Is Present, I perform every day for three months. And I like to somehow find a way to turn the performance into life. To make it timeless. I don’t want the audience to spend time watching my work: I want them to be with me and forget time. I want to open up the space so that there is only that moment, here and now: there is nothing, neither future nor past. In this way you can extend eternity. This means being present.”

The retrospective was divided into two parts. The first, hosted on the sixth floor of the Joan and Preston Robert Tish Gallery, gathered together a series of remains and relics of Marina’s artistic history. On exhibit was a documentation of about fifty works from the artist’s 40-year career including videos, installations, photographs and early interventions. In addition to this, a gigantic performative mechanism had been set up, running for the entire duration of the exhibition and generated by participation of about forty performers engaged in the re-execution of some of Abramović’s historical works: Imponderabilia (1977), Relation in Time (1977), Point of Contact (1980), Rest Energy (1980), Luminosity (1997), Nude with Skeleton (2005). The second part took place in the large atrium named after Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron. In that space, the artist performed live from March 14 to May 31, 2010 (for a total of seventy-five days, six days a week, eight to ten hours a day), expressing the artistic act in terms of a permanent, tiring, totalizing and above all exclusive presence. “I was there for everyone who was there. I had been given a great deal of confidence which I was not to abuse in any way. People opened their hearts to me and in return, each time, I opened mine. I opened my heart to each one of them… The physical pain I felt was one thing. But the pain in my heart, the suffering of pure love, was much greater.”

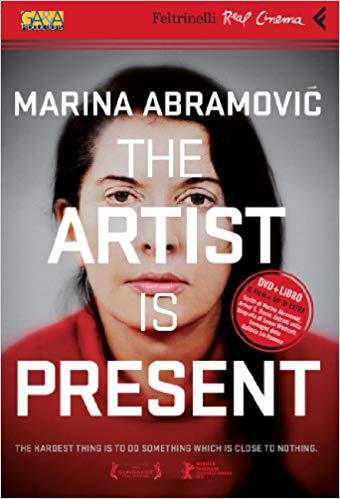

Documentary made by director Matthew Akers: Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present.

Initially Abramović had structured her big encounter with the public differently, as can be seen in her exchange of ideas with Thomas McEvilley. She would have liked to enter a space used to meet the public without any project in mind, arguing that the only thing needed would have been the creation of the space and the time of action: “what interests me is to create a situation where I am there with the public. And then something will happen at that moment.”

Abramović, before the retrospective in her honor and the subsequent performance, underwent strict preparations. In preparation for the performance, she forced her body to immobility, depriving herself of the possibility to eat and drink and to get up from her chair in anticipation of rendering a possible paradox: the disappearance of the individual and the appearance of the artist.

Inside the Museum’s atrium, Marina Abramović created a charismatic space whose perimeter was marked by a white ribbon on the floor. Four beams of light from four spotlights were arranged at the corners of the square, illuminating the core of the scene in which the artist, wrapped in a long dress with only her face and bare hands exposed. Separated by a table, Abramović sat mirror style to an empty chair across from her, ready to receive members of the public one at a time. The performance, studied in detail, was reduced to a minimal scenography that took on the appearance of a film set. Writing in Artforum, Carrie Lambert-Beatty proposes a double reading of the event, underlining that if inside, the performance appears guided by a sincere and mental sharing made possible by the high levels of concentration, “but I know from out here, it looks like performance art is entering the Museum of Modern Art in the form of unabashed celebrity worship.”

Here, one could bring Guy Debord into the conversation. It was he who, already in 1974, defined “spectacle” as “the inverted image of society in which relations between goods have supplanted relations between people,” pointing out that “passive identification” with spectacle has radically supplanted “genuine activity.” We watch, but do not interact or participate, as the plaque on the wall of the museum atrium hosting Marina Abramović’s performance says: “Sit silently with the artist for as long you want.”

“The alienation of the spectator to the benefit of the contemplated object (which is the result of his unconscious activity)” continues Debord, “is expressed as follows: the more he contemplates, the less he lives; the more he accepts to recognize himself in the dominant images of need, the less he understands his own existence and desire. The exteriority of the spectacle in relation to the man who acts is manifested in the fact that his own gestures are no longer his own, but of another who represents them to him. It is for this reason that the spectator feels nowhere near himself, since the spectacle is everywhere.”

The spectacular apparatus in Marina Abramović’s performance was fueled by the pressure that the market tends to exert on performance art in order to document and sell the artistic action. The members of the audience, one at a time, sat in front of the artist, taking the prescribed attitude and becoming the object of countless gazes: individual, collective, photographic. The overall experience was inscribed in the spectacular dynamics that the staging, the lights, the other spectators and the managers of the event contributed to create. The Artist is Present established a forced hierarchical relationship between the artist and the audience due to an inevitable code of conduct, which included the censorship of the participants’ spontaneous action by security guards, imposed by the success of the performance. “It is the oldest social specialization, the specialization of power, which is at the root of the spectacle. The show is thus a specialized activity that speaks for all the others. It is the diplomatic representation of hierarchical society in front of itself, where every other word is banned.”

A similar process of glorification of the artist was already visible in the photographic project The Kitchen, Homage to Saint Therese (2009), in which Abrahamovic tried to create a sort of sacred iconology of her own image, comparing herself to Saint Theresa of Ávila. However, The Artist is Present undoubtedly marked the achievement of much wider audiences and contributed to strengthening the iconic status of the Serbian artist. There were around seven hundred and fifty thousand visitors who comprised the audience that attended the retrospective, followed by the media success produced by the documentary Marina Abramović: The Artist in Present in 2012.

Documentary made by director Maura Axelrod: Maurizio Cattelan: Be Right Back.

The increase in recent years of artist documentaries produced by well-known brands in the entertainment industry is also indicative of the expansion of the cultural industry and the spectacular logic that permeates contemporary art production. United Talent Agency, a flagship institution in the representation of artists and professionals in the entertainment industry, is involved in film financing, branding, licensing, and since 2015, has extended its division to the Fine Arts sector.

One of the UTA’s first experiments, defined by the agency as an example of “cross-pollination”, was Maurizio Cattelan: The Movie, a documentary made by director Maura Axelrod. The interest, on the part of agencies dealing with the entertainment industry, to offer artists new market opportunities in the visual arts world was created in light of potential new profits for market players: “Agencies can rely on several artists who become multimedia phenomena, such as Mr. Arsham, Julian Schnabel and Mr. McQueen.” A combination such as this enshrines the construction of a social representation of the artist, who, like a Hollywood star or rockstar, invests in promoting himself through the circuits of the global entertainment market. As Massimo Melotti would put it, we are in the phase in which, as Marshall McLuhan claimed, “the medium is the message.”

“The phase in which the content to be communicated, the object of communication, takes second place to the medium that is used to communicate. In turn, through this function, it is able to modify the social relationships between groups and individuals. The commodity is the medium, the object the content. But an object that can only communicate a part of itself. The extreme phase of consumerism in which the commodity is no longer an object, it is no longer material; it becomes the means of communication and then again immaterial and virtual, available to the unknown universe of the Net. Consumerism interacts with communication, first and foremost, at the level of expansionist logic, borrowing from it its specificity. Our society, which by its nature tends to emphasize more and more consumption to encourage production, promotes the idea of the communicational message as a consumer good. A valuable asset in that it is aseptic, malleable, producible and distributable at a low cost. Communication can count on a technology that tends to move from the world of the atom to that of the bit.” Economy of presence and monetization of presence: do we require a new conception of the unity of individual work?