Toasts and Ghosts

Tolia Astakhishvili’s “To love and devour” at Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation

Among the many new art foundations recently that hosted opening receptions during the Venice Architecture biennale days, the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation stands out on more than one count. On the one hand, the sheer artistic quality of its inaugural project by Georgian artist Tolia Astakhishvili—visceral, unsettling, difficult to commodify—and on the other, its deliberate rejection of the trending Palazzo Veneziano routine: fresco restorations, piano nobile receptions, and golden-hour views over the Canal Grande. Following the lead of early pioneers like Fondazione Prada and Pinault Collection, this is indeed the classic case, as European moguls and tycoons are choosing to establish their residency in Venice, drawn by the incentives of the flat tax, to invest in prestigious properties and establishing art foundations in the process. Several significant examples have emerged in recent years, such as Fondazione Ama Venezia, owned by collector Asscher; Palazzo Diedo, owned by Berggruen Arts & Culture (purchased along with Palazzo Malipiero and Casa dei Tre Oci); Casa Sanlorenzo, managed by Sanlorenzo Arts, the cultural branch of Sanlorenzo Yachts. Dries Van Noten will be the next.

These foundations may vary in ambition, but they all follow the same Palazzo Veneziano fashion: a carousel of blue-chip artists, with a prestige-driven programming, and with settings ideal for indulging in pomp and splendor—perhaps slightly tipsy on prosecco. While million-dollar worth art hangs on restored walls, the party often overlooks, if not ignores, the fragile local art ecosystem: a handful of artists, curators, students, and gallerists who still resist extinction in the city.

The Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation goes against the tide. Rather than launching with grandeur, acquires an unfancy property—and instead of restoring it to lavishness, invites an artist to spend months in the city, offering space and budget to work directly in situ. The result of this effort is exceptional, for its artistic quality, and the work sets in motion a virtuous cycle—one that involves construction workers, architects, gallerists, and designers alike—creating, for them and for the city, an opportunity that transcends the glamour of the vernissage.

In this exemplary setting, curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, a long-established presence in the art world, was invited to facilitate the work of artist Tolia Astakhishvili. Together, they managed to rekindle some of the spirit of early-2000s relational aesthetics—a time when artists engaged with radically different setups, were invited to experiment with materials, and disrupt spaces. Tolia Astakhishvili’s (b. 1974) work is indeed emblematic of her generation, and her language can undoubtedly be aligned with the legacy of fellow installation artists. It also signals a renewed interest in those tropes which, after having been stretched thin, were left to rest—only to return now with fresh relevance.

It seems increasingly clear that the paradigm of live performance—which has defined the tone of many institutions in recent years—still benefits from reconnecting with its precursor, in a genealogy of the Gesamtkunstwerk (as Obrist likes to define it). This approach reached indeed a relevant peak in the late 2000s, when artists would often strategically use available resources—time and budget alike—to produce in situ works, aiming at merging the artwork into life, and making it inseparable from the architecture and the exhibition space itself.

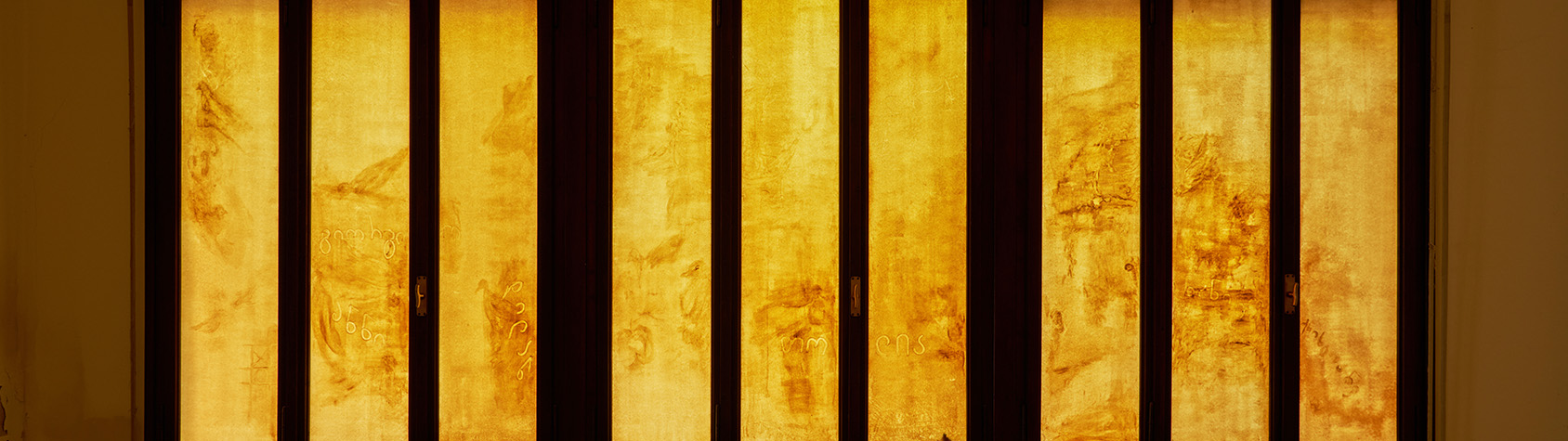

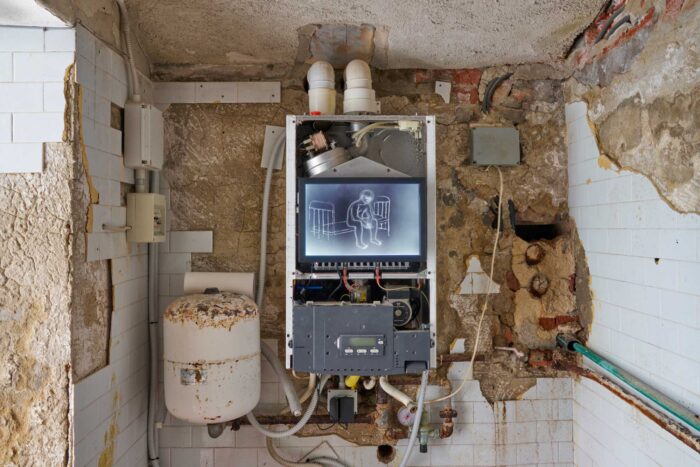

In line with this approach, the rooms of the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation became the stage for the artist’s intervention. Astakhishvili was given access to the property with no prior renovation carried out by the foundation—an unusual but deliberate decision. The modest two-storey palazzetto—formerly the home and studio of early century painter Ettore Tito—still bears traces of its past uses, from its former destination as studio-house to later fragments of life as an office and a small guesthouse.

Beginning in January 2025 and continuing over the following months, the artist lived and worked in Venice, gradually transforming the space into a spatial artwork. Her intervention unfolded across multiple layers, involving both her own gestures and those of invited collaborators. Consistent in approach with other recent exhibitions of hers, the interventions tend to saturate the space with dozens of small and big gestures, which create a semi-chaotic sequence of views, atmospheres, and situations.

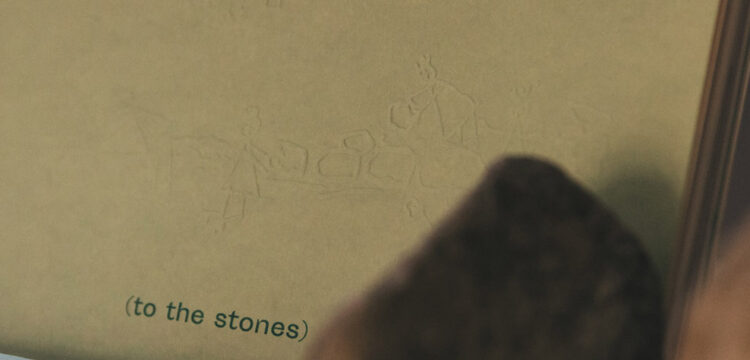

This time these interventions include: removing bathroom walls while leaving the pipes exposed (my emptiness, 2025); obscuring a window and covering some furniture parts with newspaper collages (I can’t imagine how I can die if I’m so alive, 2025, with Zurab Astakhishvili); installing a big photograph on a narrow corridor-like space (Heike Gillmeyer, Prospective Dream, 2010); removing the top half of a small bathrooms walls, and placing an architectural model inside (house of mending, 2024, 2025); arranging found objects, Murano glass, and a toilet on the floor (universe, 2025); transforming the top of a staircase into a bed with black sheets (I’m also sad when I sleep, 2025, with Thea Djordjadze); installing a video work—made with AI? [from here to there, (sidewalks), 2025, audio by Dylan Pierce]; building a plaster wall next to a brick wall, making the room smaller (when the others are within us, 2025); laying drawings framed in transparent plexiglass directly on the floor (a timeline with physical attributes, 2025); placing a grey cardboard model of a rationalist building on a found metal base (suddenly, the world becomes loud II, 2025, with Zurab Astakhishvili).

These gestures accumulate delicately, like dust on a shelf. They evoke the quiet curiosity of stepping into the home of a long-lost uncle—someone we haven’t seen in twenty years. It asks us to walk into the room with respect, as if we still owed something to the soul of the departed, making sure we won’t upset his ghost. The vernacular arrangements slip into surreal configurations, and the physicality of the objects blurs into the ethereal. The effect is ubiquitous. As I move from room to room, I feel as if I’ve stepped into the artist’s mind: full of memories, haunted by fears, aroused by desires.

It feels reassuring and estranging, I’m puzzled. The many traces Tolia left lead to no exit, and I find myself circling the space multiple times, as if I were walking back to the same corner again and again, hoping to find the key that would let me decode an untold enigma. Each time I return, I notice a new detail—maybe even a new artwork—that complicates and troubles my desire to understand.

It also makes me think of Marte in Gaia e Cosimo vs sotto il monte Sinai, Parascha passo 32, the seminal work by Jorge Peris, presented at Micamoca (now Callie’s), Berlin, in 2008. In a similar spirit, Peris had responded to Mariano Pichler’s invitation to create a show by requesting a few weeks to work directly in the space. There, too, he carried out a series of disjointed, visceral interventions—many of which still linger in my memory.

He dug a hole in the floor to reveal a buried staircase; suspended an active air compressor with ropes above a visitor’s path; relocated a 10-ton safe from the top floor to the basement; sprayed sand at that safe with an air compressor; embalmed octopuses with salt; and cultivated mold colonies on yogurt cans. The brick walls of the former Berlin factory felt alive, haunted, torn by winds—rotting like a swamp.

While the two artists may converge in typology, they diverge in tone and intention. Astakhishvili’s interventions are rather unimposing—and at times, even ironic. What I appreciate most in her work is the radical appropriation of architecture through recurring tropes: the maquette and the drywall. Interestingly, drywall’s materiality inevitably recalls classical sculpture, while its industrial origins resonate with minimalist practices. It is a warm, receptive material, and Astakhishvili uses it as a support for less rhetorical elements such as coffee, artificial snow, or cutlery.

One in particular—taste (snoring and the sound of pigeons), 2025—is a massive rectangular volume that sits on the ground floor. It is one of the most intriguing and ambiguous works in the exhibition: not quite a pavement, not a plinth, not a bench—nor even a minimalist box meant for contemplation. Yet it fiercely occupies the space, unapologetically, almost carelessly, too large for the room. As spectators, we are forced to walk around it. Our movement is constrained; it takes up our space. We cannot walk on it. We cannot sit on it. We are compelled to confront the mute materiality of the object’s presence. A number of flattened pieces of cutlery are embedded in its surface, hinting at a possible narrative—just a hint.

I stood there for minutes, indulging in estrangement, savoring the sweetness of a mellow memory I couldn’t fully recall—until, stepping outside, the bright sun of May pulled me back to reality.