Time Out of Mind

“The Last Terminal: Reflections on the Coming Apocalypse (Part 5— Vibrato)” at Rib

Angie Keefer reacts to the exhibition The Last Terminal: Reflections on the Coming Apocalypse (Part 5— Vibrato) at Rib, Rotterdam. This is the 5th chapter of a collective review of an exhibition that continues to change, as in their program, Rib gradually adds new works and replaces some of the existing ones, building a narrative that evolves whilst rethinking their pathways and future.

Don’t compare yourselves to others. You are giving away your raw psychic energy, the joy of creation. You are giving away your sexual energy. You need to look within yourself and ask yourself, “Who am I?” You’re not your mother. You’re not your father. You are the Self-God. Any last questions?

Directly across from the single-occupancy laptop booths in the newly remodeled airport lounge, two little girls sit quietly waiting for their parents at a polished wooden dining table, watching as a man with a booming voice addresses an audience apparently gathered inside his computer screen. Elegant sculptural lamps with brass shades and expensive coffee-table photo books populate the long display shelf attached to the wall behind the girls, conjuring the do-not-touch domesticity of upscale contemporary furniture stores.

That’s a great question. The ego is based out of the body and the mind. When the body and the mind come together, they form the ego. The mind is important because it’s the filter between the brain and you. But the mind is not the spirit. The soul, the spirit—the spirit is above the soul. I’ve noticed in many cultures the spirit and the soul are the same, but the mind is a unique being. Mind is mental body. Look at the man or woman in the mirror every morning and remember: You. Are. Not. Your. Body. And POOF! You’ll have an experience—the experience of ego death.

The laptop booths, partially enclosed by a low roof but otherwise completely open to the rest of the bustling lounge, provide scant sound absorption for the man’s unusually loud voice, while his headphones prevent anyone from overhearing whatever it is that people might be saying back to him from the other end of a satellite signal.

You’re welcome! Beautiful! I’m so happy you’re sharing! That’s excellent!

As the man nods and laughs approvingly at his screen, the older girl turns and whispers in her sister’s ear, carefully cupping her hand to form a secure tunnel for their private exchange. The younger girl’s eyes widen while remaining fixed on the man. Her sister slides closer and drapes a protective arm around the girl’s small shoulders just as their parents arrive, carrying buffet plates stacked with miniature sandwiches and glasses of apple juice.

Thank you! That’s beautiful! Thanks for sharing. Man in the mirror: that’ll explain the whole thing. Focus on your breathing. Stand strong and bold in your personal energy—your GREEN energy. Own it. Feel it. Ooze it!

Looking back on art of the 20th century from the vantage of 2010, a certain academic linguist (b.1931–2015) made a succinct attempt to comprehensively analyze the present state of artistic discourse, which they published in pamphlet form via an independent imprint currently affiliated with the University of X. In their essay, called ____, the linguist set out, in part, to answer a complaint regarding art criticism penned by a slightly younger art historian (b.1955–) a few years earlier, in 2003, and published at that time in this same series of pamphlets under the title ____. The series itself had originated with a couple of anthropologists at another university, who were seeking to facilitate dialog across academic fields by disseminating pithy essays from renowned thinkers busily grinding assorted axes in various corners. Thus, the art historian lamented that despite the current and increasing proliferation of art writing—whether journalism, criticism, theory, or art history—the field seemed increasingly unable or unwilling to make qualitative judgments about works of art. And thus, the linguist responded seven years later that the incapacity of experts to conclusively judge the quality of artworks, or even to definitively differentiate artworks from other categories of objects, is not a failing of art criticism, but (simply) an indication of the collapse of art itself as a meaningful supercategory of knowledge. Well, then.

What is a “supercategory of knowledge,” and how does one collapse? To illustrate, the linguist referred readers to the collapse of religion. Whereas once upon a time we appealed to the gods to remedy a drought, scientific means have since emerged to provide a more reliable account for meteorological phenomena (not to mention a repertoire of techniques for effectively irrigating crops in the absence of rain). Today, the sorts of questions people formerly looked to religion to answer are better addressed by other categories of knowledge that provide more demonstrably useful tools. The linguist writes:

There is a certain amount of historical evidence about what happens to supercategories when they collapse. The supercategory of Religion is a case in point. Since its collapse in the 19th century, the main issues that would have been discussed under its auspices are now distributed under other rubrics. These rubrics include ethics, economics, politics, and race. But no one any longer thinks of the issues as having a primarily religious dimension. They are discussed as aspects of the relationships between human beings, not as aspects of the relationships between God and the human race. Similarly, explanations once supported by an obsolete supercategory are no longer seriously advanced. They are replaced by other explanations. No one nowadays supposes that earthquakes are manifestations of divine anger: the religious explanation has been supplanted by a geological explanation.

That is, when your planet is enmeshed in digital communications networks, surrounded by satellites, and able to assess its own workings through exponentially growing zettabytes of data generated and processed by nano-miniscule machines numbering in the trillions, the persuasive power of mythological frameworks for comprehending life’s vicissitudes will wane. Of course, that “no one nowadays supposes” divine anger precipitates an earthquake is an overstatement—wishful thinking, perhaps, on the part of the linguist.

Breathe in. Quantum DNA. Believe in My Personal Green Energy with every fiber of my being, now. Breathe out. Believe in My Personal Green Energy with every fiber now. Quantum DNA. MY PERSONAL GREEN ENERGY.

The parents observe the man in the booth, exchanging glances with one another as they distribute sandwiches and drinks to the girls.

What’s the opposite of shark!—the younger girl initiates a quiz game with a sudden shout, as if jarred into consciousness from a state of deep hypnosis.

The opposite of short?

NO! SHARK!—the other girl barks.

Answer is fish! You’re too slow!

Ok, how many bones does a shark have?—not to be bested by two small children, their father attempts to regain dominance over the girls with a trick question, but their attentions have already reverted to the man in the booth, who is now rocking back and forth rhythmically as he chants.

None! They’re all cartilage!—Dad exclaims to no one listening.

Personal Leadership in Green Energy is creating my reality. Breathe in. Feel the supreme comfort. Breathe out. Personal Leadership. Feel it. Ooze it. Breathe in. Personal Leadership in Quantum DNA is creating My Green Reality. Yes, it is. Breathe in. Yes, it is. Breathe out my green reality.

One tell-tale sign of a collapsing supercategory, the linguist explained, is the fracturing of related discourses. Hence, the veritable wealth of acrobatic, baffling, and inconclusive art writing the art historian chronicled in their essay. The linguist helpfully sorted the sum of such discourse produced over the past hundred years or so into three basic frameworks, all of which solidified in the decades following the explosive provocations of Dada (c. 1915–20), and its anti-art ambitions, which blew open the rhetorical flood gates, hastening art’s supercategorical collapse. (On the off chance that this text has fallen into the hands of a non-initiate, “Dada” names a loose and short-lived movement among a small community of artists working around the time of World War I, then known as the Great War, as it had not yet been understood to be merely the first of others to come. Recognizing the irrationalism of a “great” war, these artists intended to subvert the esteemed cultural values that had nevertheless enabled such a travesty by embracing absurdity, devising an irrational art to mirror rather than mask the world they encountered. They proliferated energetic nonsense in lieu of pretty pictures. Dada was defanged and domesticated within a few years by the legitimizing mechanisms of cultural institutions—discourses and markets—which had absorbed it with ease by the mid-1920s. But if the linguist’s analysis is correct, the artists ultimately prevailed in their efforts to undermine the sanctity of artistic tradition, activating a revolution in meaning-making that has confronted critics and theorists, as well as artists and their publics, with the patent illogic of “art for art’s sake” ever since. The absorption of Dada into the machinery of artistic valuation exposed and thereby demystified the workings of that system, which, as it turns out, is largely driven by mystique.)

Right. And what are these three frameworks, you’re dying to know? They are logically insupportable efforts to describe and defend the category of art in the absence of any obvious and definitive categorical markers.

- Idiocentric — The thing (the art) is what I say it is. Art works are works made by artists. Artists define what works of art are.

- Institutional — The thing (the art) is what we say it is. Art works are made by the institutions of art. Institutions collectively confer artistic status to objects.

- Conceptual — The idea is the thing (the art). Art works are ideas, not to be confused with material artifacts. But, practically speaking, we only recognize them as such because they are materialized and institutionalized.

According to the linguist, today’s art theorists (and anyone else attempting to speak or write meaningfully about art) generally “take refuge behind descriptions which [don’t venture] beyond supplying factual information about the work in question” because “the collapse of the supercategory leaves them without any clear idea of what a ‘work of art’ is.”

After a half-dozen guided breaths, the girls notice their sandwiches.

I brought two dresses—their mother informs their father, fingering her phone screen.

Which ones?

She flicks through some photos as he looks over her shoulder.

That one’s bold—he volunteers. She looks up from her phone and squints in his direction. And also beautiful—he clumsily assures her as the mantra-speak of the man in the booth rises to a crescendo.

PERSONAL. LEADERSHIP. ENERGY. BEAUTY. BOLD BEAUTIFUL PERSONAL ENERGY. PERSONAL GREEN CRUNCHINESS. BEAUTY. MY PERSONAL CREATING MY REALITY.

A silky-bloused woman stationed slightly farther afield in the leather armchair section of the lounge glances up from her computer, briefly making eye contact with an older man in a suit who is seated a few chairs closer to the window wall, where he, too, is assessing the threat level of the burgeoning situation over at the laptop booths.

BEAUTY. YOU ARE A WINNER. BEAUTY. YOU’VE GOT WHAT IT TAKES TO BE SUCCESSFUL. BEAUTY. PERSONAL LEADERSHIP ENERGY CREATING YOUR REALITY. BREATHE. PERMEATE. OOZE. BREATHE! BREATHE!

When I accepted this commission, I made clear that I wouldn’t write about the works in the exhibition, because I don’t have much, if anything, to say about individual art works. That was not entirely true, because I say a lot about individual art works in the daily course of doing my job as a teacher of graduate art students who are in art school to make art works and hear what other people, especially teaching faculty, might have to say about them. What I meant, more precisely, is that I rarely, if ever, have anything to say about individual art works that I believe is also worth committing to writing and making available for others to read as such. This dearth of worthy words is not attributable to some supposed fault or lack on the part of art works. It’s a judgment I make about the value of most things that can be said (by me) about single art works and a related judgment that live conversation among present human beings is the fitting beginning and ending for all those words. Nevertheless, I spent an hour at the small gallery—a non-profit, one-room enterprise occupying a storefront on a side street in a working-class immigrant neighborhood on the outskirts of Rotterdam—where I chatted with the director about the show while holding a coffee in one hand and capturing a few images on my phone with the other, all in anticipation of writing … something. One thing the director told me regarding the exhibition, the thing I haven’t since forgotten, is that he has “no idea what it’s about.” A refreshing attitude, I thought. The other thing I remember well is that, according to him, the space formerly housed a butcher shop, and, before that, a jewelry store.

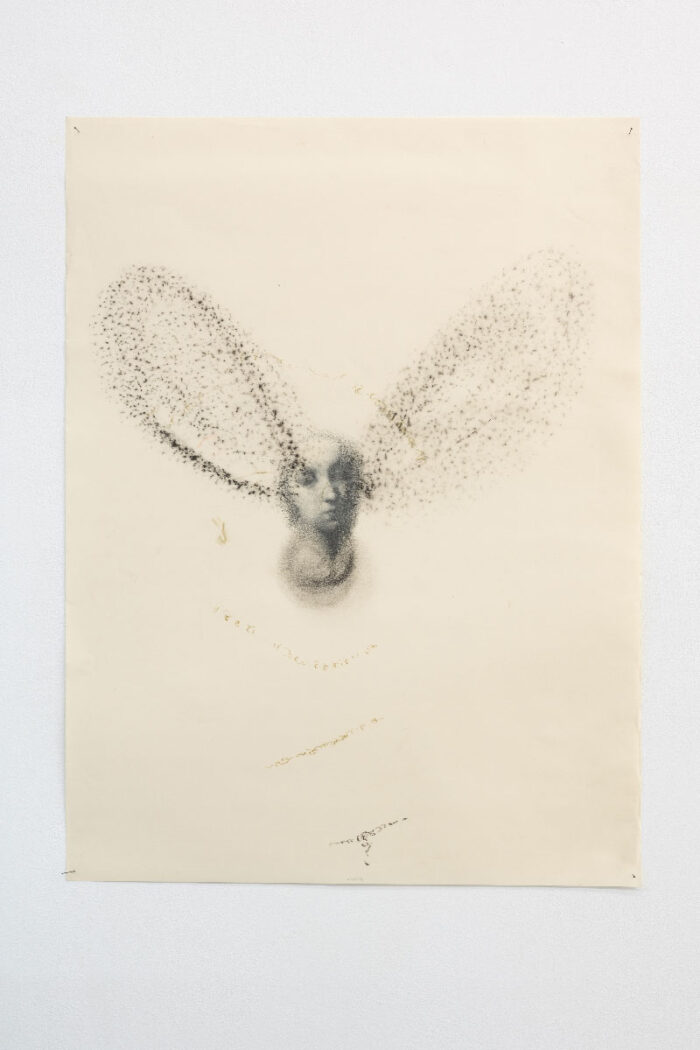

While half-standing on the makeshift mezzanine, where vertical clearance was not-quite-adequate for my upright posture, I spied a beautiful stripe of stained glass in a pixel-y pink and green art deco pattern, which ran the full width of the narrow shop above the tall front window—roughly eye-level if your neck is bent and your head is brushing the ceiling. A relic, I assumed, from the more glamorous jewelry vending days of yore, this unabashedly decorative and pink flourish seemed out of place in the shop’s current guise, its original décor stripped and scrubbed to the bright white, utilitarian clarity that has been de rigeur in art gallery architecture for over a century, the better to align the enterprise (aesthetically, at least) with the actual loci of contemporary power that are science and industry. The stained glass, perhaps initially conceived of as an ordinary and necessary bit of ornamentation, lingers on in this less ordinarily and necessarily ornamented age as a meager monument to time long out of mind.

Me, me, me, me, me, me, me, me, me!—the younger girl blurts out, improvising a melody to transcend the circumstances, which have grown dire.

That’s a nice song. What do you call it? The me song?—Dad responds without looking at his daughter while Mom continues reviewing the contents of her phone. The older girl’s mouth hangs open as she studies the booth man, her lips forming a tiny circle of concentration.

Me, me, me, me, me, me, me, me, me—comes the younger girl’s reply, meeker this time, almost frightened.

Bring back your personal power into the room now. That’s it. Breathe in. Breathe out. That’s it. Your Personal Being. Period. Never rely on others. Return to the here and now. I’m free. I’m free. I’m free to be me! Thank you all. Enjoy. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. Looking forward to seeing you next week. Ciao! Merci beaucoup! Thanks. Bye, bye, bye, bye, bye.

The man closes his laptop and packs it into a satchel secured to the top of his wheelie bag. He stands up from his seat at the booth, stretching his arms in a victory posture while arching his back and emitting a wide yawn. He places a white Panama hat with a light pink ribbon on his crown at a slight forward angle, then crosses the lounge to the bar where he vigorously embraces a stocky woman in pale lavender leggings and matching sweatshirt who is waiting for him there with two full glasses of complimentary sparkling wine.

Meeting adjourned, I hurried back to the bus stop under cold winter drizzle, a copy of the press release and a transcript of one of the videos tucked inside my coat, and began the long wait for a good enough reason to write. The agreed-upon deadline came and went, followed by several more months of silence on my end.

A first draft—the preceding text, which you have perhaps just read—fell completely flat. What about the exhibition? The works? The artists? Also, the storefront was formerly a perfumery, not a jewelry shop. Were you even paying attention? Of course. I mean, I thought so. The effort was not to describe the works nor decode the exhibition, but to enter the logics they modelled. What were they up to? How were they going about it? Why were they bothering to do so? Was the exhibition a direct (or directed) conversation? Or some more diverse and digressive event? I perceived the latter, though I was consistently struck by the intellectual complexity and existential doubt each piece seemed to entangle all on its own. Ambivalence—about purpose, faith, reason, pleasure, materiality, history, the possibilities of art itself—pervaded and prevailed. Can one grasp and shrug at the same time? Or are those urges mutually incompatible? Yes and yes? In my memory, the show is greige, like the weather outside on the day I visited, punctuated here and there by a rejected red balloon lurking in some corner, or the marred emerald green of a storied plinth, now promoted to the role of artwork. The particulars matter. Particulars always matter. But in an exhibition that self-consciously rejects the competitive ethos of a marketplace, no particular ought to skew the whole. So, then, what of the whole? I suppose if I were an art critic, I would try to persuade you that the exhibition conveyed a degree of skepticism towards aspirations of many stripes, or even a high degree of skepticism, if not outright shame, towards aspiration in general. I hesitate to write that, concerned the words might be interpreted as an indictment or a negative judgment (the logics of the marketplace aren’t so easily suppressed), when in fact the sentiment seems to me a worthy one for artists to bring to conscious awareness by way of their collective examination so that we may all consider it more carefully. In an age characterized by disbelief, what do we do with our need to believe? What art do we produce from our thwarted impulses? What might it say to a future?

…