The When of Art

Sensibility After Visibility

How does art announce itself today, when images float freely—divorced from stable institutions or authorship—and sensibility is shaped as much by advertising algorithms as by aesthetic traditions? Moving beyond laments for the “end of art,” this text starts from its apparent ruins to pose a different question: not “what is art?” but “when is there art?”

In contrast to the postmodern melancholy and lament for the erosion of criteria—Lyotard’s “incredulity,” Benjamin’s aura anxiety, or Debord’s spectacle fatigue—Jacques Rancière proposed an alternative way of thinking through the question of art and its politics. He mapped a terrain of “regimes of art,” each with its own mode of visibility and intelligibility. In The Distribution of the Sensible, Rancière defines a regime as a system of sensible evidence that makes it possible to see at once the existence of a common world and the delineation of the parts and positions within it. Art, then, rediscovers its political nature, not by its content but by how it configures the space of perception itself.

From this angle, the present aesthetic regime (as opposed to the ethical or representative ones) transforms sensibility from passive receptivity into an active principle—no longer a mirror of an exterior order but a generative force that shapes what can be felt, thought, or imagined. This shift displaces long-standing ontological debates. Art is not something, but is what happens under certain conditions. The problem is not as much one of essence but of occasion and circulation.

Now, how is this aesthetic regime transformed once flattened by the generalized commodification of images? In a world where pictures circulate like currency—disembedded, de-hierarchised, and endlessly recombinable—how do we distinguish artistic gesture from design, or expression from simulation? For Aristotle, fiction was not deception but an operation of poetic construction, a kind of modelling of intelligibility. In the aesthetic regime, fiction splits: on one end, the silent potential for signification embedded in any object; on the other, the multiplication of speech-acts and layers of meaning. Today, that structure collapses into a strange double-bind: images are everywhere, yet intelligibility shrinks. The commons is saturated with signs, but the capacity to interpret them contracts into the horizon of immediate experience.

Rancière also set forth that a symbol is first of all a shorthand sign, perhaps pointing out that every act of sensibility begins in condensation, in the charge of potential meaning. If, as he insists, artistic transformations don’t emerge from technology itself but from its recognition as art, then the pervasive integration of digital tools and marketing aesthetics into visual expression demands a new framework. While technology, content, and operations jointly compose contemporary practice, it is the operational vector that retains the capacity to reorder perception. This is where a critical distinction becomes productive. The prevailing “equality of the visible” often blurs the boundaries between different forms of production. By re-establishing a distinction between art and design—parallel to the dichotomy of process versus result—we can reframe their relationship: though both are immersed in the same matrix of visibility and cognition, and despite design’s colonization of artistic language, their core operations remain fundamentally divergent in intent and consequence. This analytical separation does not seek to purify but to re-open the debate on what is at stake in each.

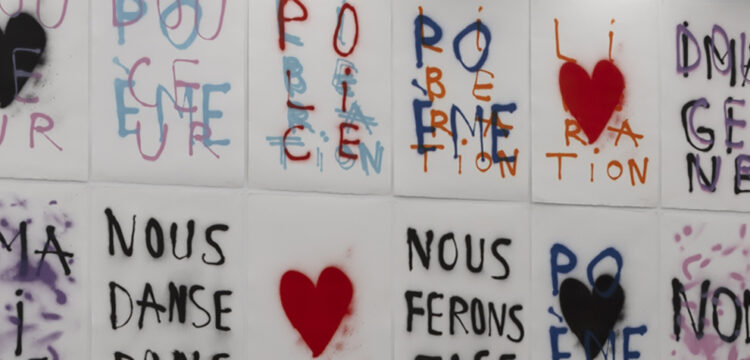

Art is not autonomous; it does not happen without a gaze that recognizes, performs, and frames it. Yet when everything can be art, we enter a regime of generalized aesthetic potential where the world is seen as a flux of available meanings. In this regime, refusal or inaction—the power of not doing—loses its distinctive ethical force, and philosophical critique risks being absorbed by a sociological description of visibility regimes. This is not a novelty; Rancière had already mapped this tension in Disagreement, distinguishing politics (as rupture, emergence, and the reconfiguration of the sensible) from policing (as order, distribution, and administration). Politics is not merely the appearance of the unseen, but the process by which concrete actions and struggles transform a given “normal” situation—policy—into a space of dispute and appearance—politics.

So again: art, as politics, is not about what, but when. Under which conditions does a sensorial experience become an aesthetic event? Can we think of sensibility not only as a faculty but as a force that may escape the names and rules assigned to it? Art would then be not a category but an intensity that interrupts the coordinates of ordinary experience. It would emerge not from the object alone, but from a configuration: a festivity, a gathering, a context, a moment. This displacement into the when-and-where is not just semantics. In the absence of clear frameworks for defining “art,” “artwork,” and “artist,” new forms of legitimacy arise.

Let’s consider a concrete example. In 2022, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York made public an exhibition that had been held behind closed doors since 1935: an annual show of work produced by its staff—security guards, administrative workers, maintenance employees, and so on. The decision to unveil this internal practice is particularly notable following the museum’s layoffs of more than 400 employees during the COVID-19 pandemic. By removing this veil, the institution performatively reframed these private expressions as public “artworks,” effectively extending the designation of “artist” to a group traditionally excluded from it. The gesture provokes a series of questions: What is at stake in displaying these pieces to a general audience? What has changed, if not the objects themselves? This seemingly minor, almost bureaucratic act lays bare the profound contingency of artistic status—its inherent dependence on context, framing, and institutional recognition. It underscores how the legitimacy of art is bound to specific circuits of visibility and mediation.

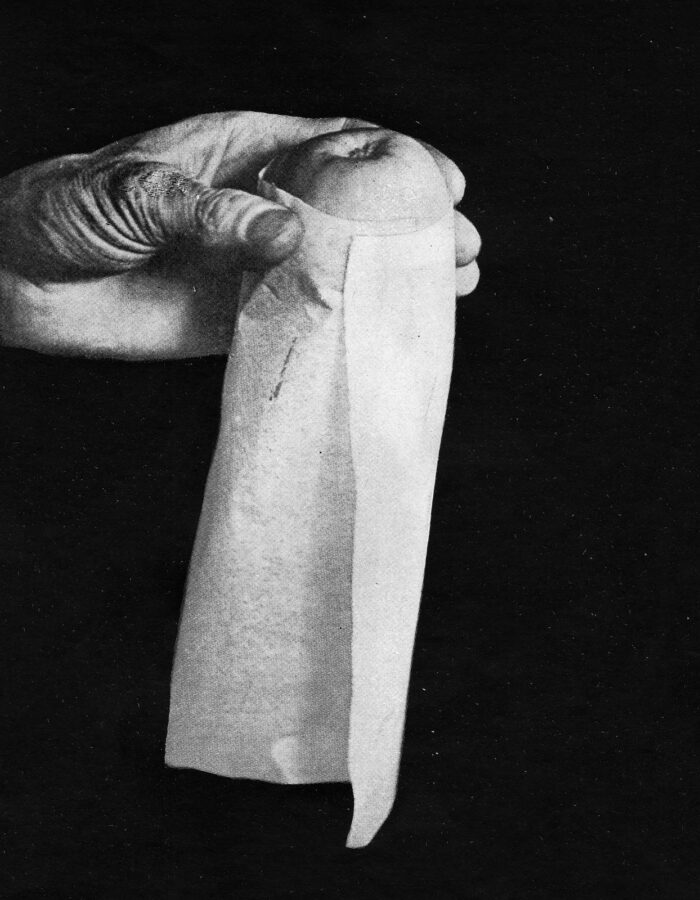

The case of the MET reveals, perhaps inadvertently, the very mechanics of legitimation, when that to be seen as art within a sanctioned frame can be more constitutive than the intrinsic qualities of the object. It thereby compels us to ask how many other potential “artworks” remain invisible, not due to any lack of merit or will, but because they fail to enter the specific circuitry where art is performed, named, and remembered. If artworks do not represent something else, but reveal a dimension of the world (or of “the truth”) immanent to themselves, today artworks speak not of an essence but of a timing. That revelation, that rupture from utility, is what turns an object into an artwork. Duchamp’s bicycle wheel does not cease to be a wheel, but once displaced, it becomes something else—an opening, a statement, a symbolic gesture.

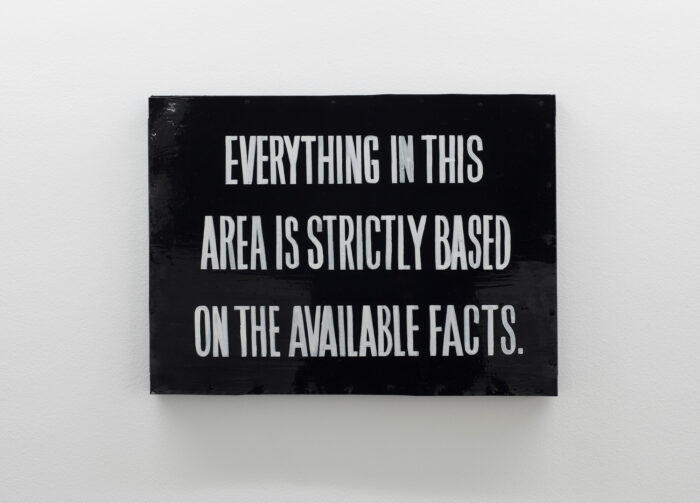

Boris Groys offers a striking parallel in a short essay, published on the occasion of documenta 13, called Google: Words Beyond Grammar. He states that the algorithmic index doesn’t understand the meaning of words—it only knows which other terms tend to appear next to them and learns from patterns of proximity and frequency. Words float in a sea of associations, detached from intrinsic sense. Language becomes probabilistic and contextual, unmoored from semantics. What Groys describes in digital grammar mirrors what’s happening in the visual field: art objects, too, are read atmospherically, their value determined not by what they mean, but by where and how they appear and circulate. If this remarks on the impossibility of distinguishing artworks from objects without contextual clues, then everything could be art—but not everything is, and certainly not always. A scrap of wire in an installation operates as a signifier; in a landfill, it reverts to being mere material.

These scenarios reveal that the constitution of art relies less on material attributes than on its activation through a specific ecology—a convergence of space, audience, and occasion that enables a gesture to be perceived as aesthetic. This process, however, is increasingly shaped by an institutional paradigm that prioritizes spectacle, entertainment, and digestibility. Within this framework, the viewer is seldom a free agent but is instead interpellated into a set of predetermined roles: the skeptic, who disputes the artistic legitimacy of the mundane; the hedonist, in pursuit of immediate sensory gratification; or the trend-chaser, captivated by the novelty of the cultural market. The very conditions that make art visible now risk confining the act of viewing to a scripted repertoire of responses. But the task is not to restore some universal criterion of art, nor to moralise about aura or authenticity. The task is to sustain practices that suspend certainty, that interrupt the obvious. And here, ethics returns not as an external judgement, but as the inner limit of the gesture itself. If there is still a promise in art, it lies in its capacity to produce conditions where the normal coordinates of sensory experience are scrambled.

This logic of contextual activation finds its ultimate test in art produced with or by artificial intelligence. In a landscape where digital processes saturate both production and perception, the “where” and “when” of art are increasingly shaped by algorithmic operations. As the digital becomes ubiquitous, and when perception is constantly modulated by recommendation engines and invisible curators, the site of the aesthetic shifts once again. Not into the gallery, nor the object, but into the fluctuating interface between code, context, and gaze where the sensible is configured, disrupted, or reclaimed.

By the way, one of the central paradoxes of AI-generated art is that it often mimics the formal traits of creativity while bypassing the conditions that make it truly transformative. Its operations are based on pattern recognition, interpolation, and recombination. What we see, then, is not creation in the strong sense, but an elegant rearrangement of existing possibilities. There is no rupture, no embodied intuition, no reflective hesitation—just probabilistic fluency. The result may be surprising, but never disobedient. This kind of output does not disrupt the aesthetic regime, but optimizes it. In a world saturated by images and governed by feedback loops, the synthetic image enters seamlessly into the visual economy with a repetition without friction. If anything, algorithmic art reinforces the legibility, shareability, and monetization of the image. It doesn’t produce new thresholds of sensibility; it perfects a way of circulation.

Perhaps, then, the fundamental question shifts once more. It is no longer what art is, nor even when it happens, but who decides on its appearance—and under what terms, for which audiences, and in what spaces. Today, art’s primary function is often not to disrupt but to organize public space. Instead of challenging perception, it makes experience seamlessly desirable, shareable, and aligned with the logic of attention economies. The rough edges of the aesthetic are smoothed into monetizable formats. The sublime gives way to the scroll; the event is superseded by the frame. And yet, a residue persists. Even within the most polished feed, one may find a gesture of refusal, a friction—not a dramatic leak, perhaps, but a quiet noncompliance, a stubborn remainder that resists full conversion into content. It is in this precarious interval, between the regime of visibility and the act that escapes it, that the question on art reclaims its critical urgency.