The Sidereal Marsh

Post Disaster Rooftops EP05

Piazza Fontana in Taranto is the designated meeting point. Where we are set to gather in the late afternoon on April 12, 2025. The modular group of steel and marble sculptural elements, intertwined with the 18th-century fountain, serves as the central feature around which the square is organized—a place of aggregation, layered memories, and urban collective struggle. Conceived by the Taranto-born sculptor Nicola Carrino, one of the most insightful and experimental figures in late 20th-century Italian sculpture, he is known for his logical-constructive approach to creating sculptures with industrial materials aimed at reimagining the relationship between matter and spatiality. Completed in 1992, the fountain—an iconic work of Italian urban planning—was designed to transcend sculpture and embrace the complex geometries of the site, activating the square at the junction between the Old Town, the main access point from the railway station, and the modern city.

From Piazza Fontana, the second weekend of the 5th edition of Post Disaster Rooftops EP05, (Extended Play 05) takes its new path. La Palude Siderale (“The Sidereal Marsh”) is the title chosen by Post Disaster, a spatial, critical, and curatorial platform born from the collaborative practices of Gabriele Leo, Gabriella Mastrangelo, Grazia Mappa, and Peppe Frisino, who share a background in architecture and social design. Grounded in a transdisciplinary approach, they have been developing a radial investigation of Taranto—its traumas and its transformative force of becoming. They chose to do so by engaging in dialogue with artists, theorists, sound artists, poets, and architects, inviting them to reflect on the city’s social conditions, infrastructural systems, and materialized memories, generating situated knowledge to be shared within a temporary community.

Since 2018, the days curated under the label of Post Disaster Rooftops, invite participants to navigate the architectural and symbolic interstices of the Taranto—with its lagoon ecosystems, the controversial legacy of the steelworks and its environmental and social damage, and the rhythmic fabric rooted in everyday life—infiltrating diverse trajectories and inhabiting marginal areas with different critical spatial imaginaries. Each time, it offers a way to explore how space is produced through practices that rearticulate static and mobile urban vectors within a relational flow. These practices temporarily disrupt the conventional “use of space,” challenging ingrained norms of discipline and activating micro-subversions through imaginative prefiguration, informed by an awareness of capital’s pervasive strategies and the role of affections and memories in distinguishing the city from mere urban life.

Thinking with the (Sidereal) Marsh

La Palude Siderale is the critical trajectory and imaginative horizon chosen by Post Disaster for its new series of transitional events, based on temporary passages through the urban spaces of Taranto—which took place from April 3 to 13, 2025. The oxymoronic tension embedded in the title, evident in the juxtaposition of the two terms, serves as an invitation to engage primarily with the contradiction emerging from Taranto’s environmental, architectural, and social landscape as a materialized “city-manifesto of crisis.” The curators state in their editorial: “Disaster is, literally, the ‘mis-alignment from the stars,’ [from Latin prefix dis-, which indicates negation or separation, and the term astrum, meaning ‘star’], a hostile condition at odds with the most favorable routes.” They then pose a straightforward question: “Can disaster be understood as a starting point toward a fortunate drift? Is the disaster ongoing, or has it already happened?”

If the “marsh”—its hydrodynamics, high-humidity transition zones, and biodiversity—serves as an opportunity to remind us that the plain of Taranto and its coastline emerged from a marsh before the early 20th-century land reclamation; “sidereal” here push to move beyond a human scale horizon with a more-than-human approach. The pedestrian pathways, the views from the rooftops of the old city, and the passages in the monumental architecture of the new district, proposed by PDR in collaboration with artists and theorists invited, must be read as experiences through which the coexistence of multiple forms of life, erased histories, and social forces can be revealed. It’s an entanglement in which the histories of slag linked to Italsider/Ilva cannot be separated from the political struggles of workers, as they merge with subjective experiences and collective desires. Likewise, the archaeology of the Tosi shipyards—where warships were built starting in the early 1900s in the Mar Piccolo basin—cannot be separated from the meeting of fresh and brackish waters, which created ideal conditions for mussel farming. These are among the key factors that have shaped the social and urban development of Taranto.

The marsh—functioning as filter for pollutants, sedimentation of solid particles, and nutrient stagnation—embodies co-creations: every “participant” (plants, animals, deposits, chemical agents, and organisms) exists in interdependent relationships, forming assemblages of matter and life. The marsh, therefore, is not merely a metaphor but an epistemological framework of proliferations, where categories such as natural, social, biological, and human are not fixed boundaries but permeable interconnections. Within this space, the real and the imagined, theory and situated practices, “above and below,” sea and land, emerge through their intra-action.

An Ecopolitical Sermon on Wet Alliances

The second City Movement of Post Disaster Rooftops EP05, titled The Broken Dream of Modernity (April 11-13, 2025), begins in Piazza Fontana. We sit or lean against Carrino’s sculptural modules and the now-dry fountain basin. Here, Giulia Crispiani activates her Paludofobia (“Marshphobia”), a pedestrian reading in two acts. As a visual artist and writer, Crispiani blends a sensual and subversive logic of sensation into language through her writing practice, destabilizing the inherent logic of domination.

Atto I. The way she reads her own text nullifies any virtuous performativity of vocal speech, embracing an intimate threshold where tenderness and assertiveness intertwine around a secret, yet without pretension. It is intentionally tuned to the low energy of the marsh. The words, almost flowing in a litany-like cadence, unfold the listener in a continuous string of phrases, with no rigid boundaries—punctuation is absent. This is a sought-after dissolution, a resistance to the constraints that organizes the flow into rhythmic segments dictated by the grammatical austerity of the language-system. This fluid progression of discourse is suddenly sparked by internal rhymes and assonances, words repeated like in a loving stutter (such as the word “mare”) or as refrains—emerging as a way to expand meaning on an affective level. What she voices is deeply infused with embodied knowledge and neo-materialist thought—from Stacy Alaimo to Astrida Neimanis—with fluctuating memories, metallic-natural sounds, and atmospheric moods of Taranto.

The phobia of the marsh, as evoked by Giulia Crispiani, is the fear that imposes order and control on stagnant ecosystems. It is the reclamation that confines, drains, paves, expropriates—reducing life to mere productivity. Revealed as a colonial and extractive project, reclamation feeds on cultural propaganda that legitimizes separation and naturalizes urban and social strategy of violence. For her, a tangible reflection of this is found in the New City of Taranto, with its vast, top-down urban plan marked by grid-like streets. Crispiani sets off a smoke bomb, a street alert—its pink soot blending with the midday sunlight, saturating the air with a dense, palpable haze that blurs the contours of nearby presences. As the words continue to take shape, the marsh emerges as a counter-force, responding to the phobia of the undefined and the unpredictable. It becomes an archive of sensory, historical, and emotional layers, existing within the chronotope of the threshold—where past, present, and future converge in genealogies that resist the linear conception of time. Giulia Crispiani invites us to leave the Carrino’s Fountain and walk slowly through the narrow alleys of the Old Town, listening attentively to the surroundings. Shaped by the rhythm of this collective movement, urban space radiates into the landscape through a sensitivity to detail, blending tactile, spatial, and vibrational dimensions as it rises to a terraced rooftop.

Atto II. The “rooftop” is the space that Post Disaster has chosen since the first edition of PDR as a site for political gathering and collective engagement, standing between the public and private. From this vantage point, one can immediately survey the city, its environmental crises, and social marginalization. The view embraces crumbling residential fragments, the curved outline of the Mar Piccolo, the tang of salty air, and the cries of seagulls. The entire maritime expanse unfolds, stretching from the Arsenal with its rusty Tosi Shipyards to the opposite shore, where the muscular silhouette of the steelwork looms. From the highest rooftop, Crispiani can be seen on a lower terrace with a microphone in hand. It is there that the text becomes a Sermon: “Blessed is the wet swamp, blessed is the mud and stagnant water, resistant to the storm…” A sensual and unproductive laudation that fuses cohabitation and geography, critique and desire, in an eroticism of the hybrid. It becomes an ode to the swamp, to the loving and sonic contact between land and sea, with its caressing waves that continue to erode every boundary; an ode to undisciplined bodies that resist normalization. “We never wanted to be all in one piece, but loose, filthy, and wet…” Crispiani’s voice becomes singular-plural, invoking multiplicity, the formless, the viscous. It invites a return to a promiscuous alliance between land and sea, between undomesticated bodies and matter. Paludofobia is thus both a lament and an ecopolitical ode, expressed in a sensitive language that shatters the logical connections between words, shifting them into an affective mood. As it unfolds its poetics of fertile disorder, it merges with the sound of bells, the laughter of children in the alleys, and the sky gradually changing color. We listen, smell, touch, and tremble.

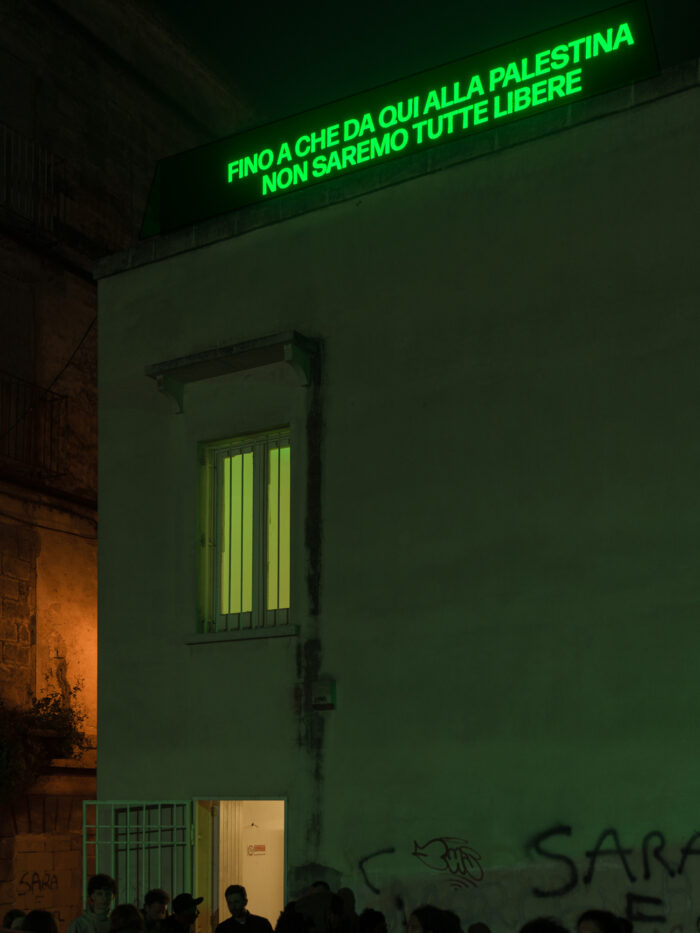

As night gradually falls, an acidic green hue envelops the terraced rooftops, setting the stage for Gaspare Sammartano’s sonic exploration. His acoustic manipulations resonate with, and amplify, the sonic world evoked in Crispiani’s sermon. A key figure in Taranto’s sound culture and a member of the Canti Magnetici label, Sammartano bases his live performance on materials from his 2021 album *Waterfront*. The work is an auditory chronicle of the city’s urban life and ecological decline, tied to the Waterfront Project—a monumental coastal redevelopment plan meant to reconnect the harbour to the city, but never realized. Sammartano’s concert offers a way of listening to the submerged histories of Taranto through a sonic fabric that weaves together the urban and natural acoustic traces of the Ionian region. It incorporates sounds recorded from the streets and the sea, along with music drawn from tapes and records found through his hyper-local research. Sirens, metallic reverberations, and echoes from the ruins of the Arsenal blend with barely perceptible human voices, bird cries, and cetacean calls, until a suspended, diffused rhythm gradually emerges. What takes shape is both an acoustic document and an imagined landscape—something emerging from the margins as manifesting of more-than-human terrain.

Gigantism, Art, Language, Technology, and Class Struggle—from Below

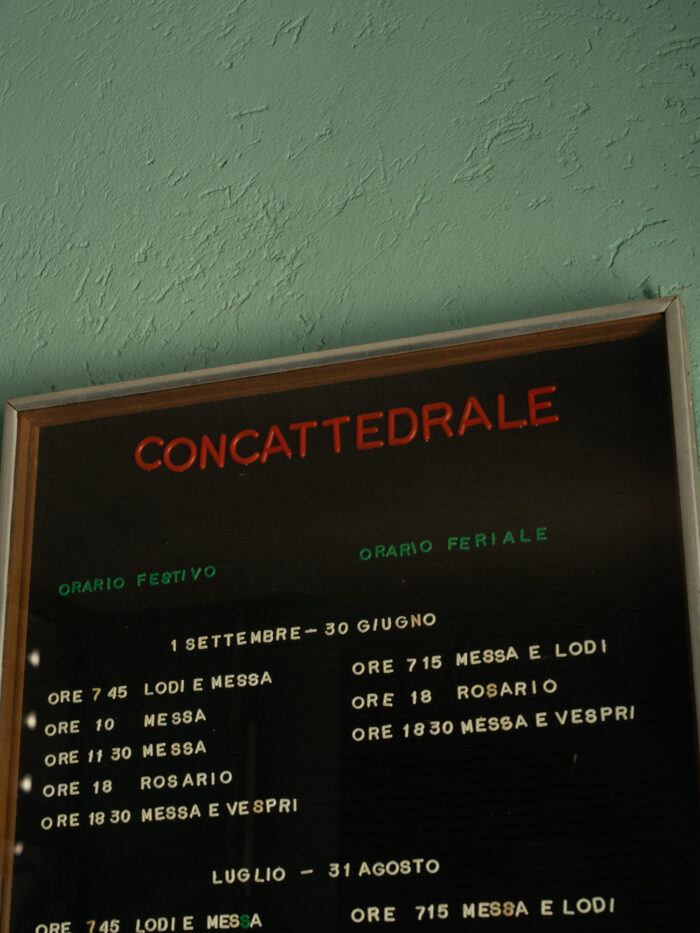

The following morning, we find ourselves in the heart of Taranto Nuova, as part of the section “Movimento Città” conceived by Post Disaster. The meeting point is the Concattedrale, Gio Ponti’s last project, inaugurated in 1970. Taranto is unique for having two cathedrals, with the historic one in the Old Town. The history of the Concattedrale is intertwined with the so-called “urban rebirth” of the 1960s, which envisioned an eastern expansion axis in response to housing demands driven by industrial requests. As we approach, we are greeted by the white façade, punctuated with hexagonal and rectangular openings, the entrance staircase, and the solid body of the building rising in front of the sail-like bell tower. Yet what is about to unfold does not center on the Concattedrale itself, but rather on its “upside down.”

The event SOTTOSOPRA: scorie, tracce, incantamenti (UPSIDE DOWN: slag, traces, enchantments) is held at the side entrance, where we are welcomed by Mario Lupano, architectural and editorial historian, display artist, and iconologist. This project is the outcome of his artistic and research residency in Taranto, shaped by urban explorations, embodied experiences, and unexpected discoveries. Together with local artist and art historian Gianluca Marinelli, they devised an impromptu underground journey through the Concattedrale’s hidden spaces, uncovering traces of the art-industry connection linked to the national avant-garde of the 1960s and ’70s—a forgotten chapter of Taranto’s history that reveals how this central hub of artistic experimentation emerged in, around, and beyond Italsider.

“SOTTOSOPRA,” Lupano explains, “is the result of rummaging. When you search for something, you turn everything upside down.” What they’ve created is a form of organized disarray—an arrangement that gives rise to unexpected discoveries. With passionate narration, Lupano launches into a critical reflection on the symbolism of Taranto’s architectural gigantism, beginning at the heart of one of its most emblematic out-of-scale buildings: the Concattedrale, an imposing structure that dominates the skyline with its monumental presence. He does so by leafing through an Atlas with oversized, unwieldy pages, laid atop a foosball table. Vincenzo Moschetti, a scholar in Architectural and Urban Composition, has created the monumental Atlas for this special occasion as guide through the pantagruelian world of Taranto, where the steel industry’s vast infrastructure embodies the cyclopean force of a city marked by “superhuman” proportions, echoing the legendary tale of the “Colossus of Taranto,” once said to guard the ancient harbor. The immense scale of the city is recognizable in its industrial architecture—from the towering blast furnaces like the iconic AFO5, to oil platforms built and shipped on colossal vessels, to the Military Arsenal and the rusting remains of the Tosi Shipyards. This outsized scale also includes civic architecture: the massive Palazzo degli Uffici, aligned with the new regular district, and the dominant Palazzo del Governo—a Fascist building in heavy brick, designed to resemble a Roman castrum in tribute to the DUX. Drawing from Hans Hollein’s Transformations series (1963–1968), Lupano reimagines its ironic and political spirit—those surreal collages of cyclopean architecture and a massive aircraft carrier stranded in a barren, flattened landscape. Among them is the former BESTAT Center, designed by Luigi Piccinato in the 1970s, characterized by its functional huge blocks. “Cyclopean,” Lupano remarks, “are the challenges posed by these out-of-scale infrastructures and objects in the post-industrial age!”

We are invited to move forward, and suddenly find ourselves directly beneath the nave of the Concattedrale. We have entered its belly—from below. It’s an odd space, especially considering its connection to a place of worship. Once a movie theater, it now houses ping-pong tables, green carpeting, and paper placemats used for impromptu target practice. The space bears traces of layered uses—recreation, storage, and more. It retains a sense of cheerfulness, or perhaps a form of competition that keeps something vital alive in its own way. The ping-pong tables have been transformed into display surfaces with their distinctive electric-blue tops, repurposed as ready-made objects. They hold materials that are found, sought after, and desired, arranged for a “hovering” encounter.

TABLE I. It displays a collection of rare editorial materials, bibliographic references, catalogs, political bulletins, and verbo-visual boards, all documenting the rise of Visual Poetry in Taranto from the late 1960s to the early 1970s. Michele Perfetti, a pioneering visual poet and staunch advocate of artistic counter-information, stands out. His works embody the utopian belief that verbo-visual language could raise class consciousness through sharp, satirical linguistic critique. Lupano explains in his speech how Visual Poetry artists, attracted by the fusion of art and technology, found a fertile ground in Taranto, with its industrial contradictions, setting up a cell for their semiological and multisensory guerrilla efforts. These materials illustrate how this art of dissent, grounded in Marxist and anti-fascist ideals, blossomed within the Italsider Cultural Circle, a workers’ after-hours club established in 1963. The circle’s mission was to reclaim personal time from labor while promoting class awareness through political and aesthetic exploration—a cultural hub for a new generation of artists, poets, and photographers. Massafra also emerges as a significant geographical node. In the 1960s, this small town at the foot of the Taranto Murgia hosted key international events such as Co-Incidenze (1969).

The table displays several publications by Perfetti, including 000 + 1 Poesie visivo/tecnologiche, Poesaggio, and Plasticity, along with a consultable anastatic edition of Frammenti quotidiani, and issues of Tecne magazine, directed by Eugenio Muccini, a central figure of Gruppo 70. Also on display are leporelli that distill slogans, images, and themes, blending critique with dominant styles, highlighting the social consequences of new social rituals presented as wellbeing and opulence, all within a context of widespread alienation.

TABLE II. Mario Lupano encourages us to explore the relationship between art and industry: local artists, working in informal painting or sculpture, began incorporating metallic materials from the steel industry, shifting toward kinetic art. The figure of Franco Sossi emerges as central. A militant critic who profoundly influenced the artists, he theorized the concepts of the “multiple” and “multiplied art.” On the table is the cover of the book “L’oggetto ‘inutile’”, which features on the cover a programmatic statement: “By challenging the concept of the ‘unicum,’ ‘the multiple’ removes art from the hands of a few privileged individuals, bringing it closer to the masses, whose role as protagonists in history becomes increasingly evident. Created with industrial production techniques, ‘multiplied art’ plays a crucial role in the collective development of society.” The celebration of the “multiple” represents an art created through industrial techniques to produce “useless” objects, as a form of aesthetic opposition. We can also see an article by Gillo Dorfles, published in Quindici (n. 9, 1968), highlighting the national debate sparked by the art market’s focus on the unicum, “beloved by collectors and museums.”

TABLE III. This table centers on Mail Art, a form highly regarded by visual poetry artists and certain publishers in Taranto, including those from Punto Zero, an experimental workshop and documentation center linked to contemporary art. A pivotal space capable of bridging both national and international art experiences, it significantly influenced the fervent verbo-visual research, channeling it into political messages aimed at citizens during key referendum campaigns. Mail Art is presented through original postcards from the 1970s, each bearing texts on the reverse that address major social issues of the time, such as housing, domestic violence, and abortion. These postcards are authentic multiples created by leading artists, who sought to highlight the interference of the Catholic Church in social life, the imaginary shaped by the economic boom, and the obscurantism of a patriarchal, male-dominated society.

Lupano passes the baton to Gianluca Marinelli. We now find ourselves beneath the staircase of the Concattedrale, surrounded by its concrete pillars, hosting a series of video installations. Marinelli invites us to reflect on the figure of the “artist-worker,” an interstitial subjectivity that challenges aesthetics and transforms them into a field of critique, exposing the intersections of production and creation, alienation and struggle. On the vertical panels next to the tables in the previous room, a collection of materials related to the artist-worker of the Italsider Cultural Circle—newspaper clippings, lists of unknown names, photographs, drawings, and exhibition flyers—was already visible.

Here beneath the staircase, a silent video by Marinelli introduces a long sequence of documents, articles, dispersed archival images, and art catalogs referencing exhibitions by artist-workers. One such artist is Ciro Quaranta, who began working at the steel plant as an electrician at the age of sixteen. He joined the Italsider photography lab and started documenting workers’ protests, urban dynamics, and the city expansion from the late 1960s onward. He later left the company to pursue a successful career as a professional photographer, exploring other labor realities across the Apulian region, often adopting a magical realism style. However, Italsider is not Taranto’s only industrial giant. Another major player was Belleli, a company specializing in oil platform construction. In the late 1990s, Belleli built “Ursa,” the world’s largest oil platform, and Quaranta persuaded the head of personnel to grant him access to document its construction for two months. In another room, two distinct artistic experiences by artist-workers are presented: Antonio De Franchis and Antonio Rolla. Their works represent contrasting moments in the evolving perception of Taranto’s industrial landscape. In 1969, De Franchis’ audiokinetic environment still reflects the optimism of the economic boom—a programmed artwork that directly engages the spectator, symbolizing a period of hope tied to industrial growth. A decade later, in 1979, Rolla’s mural, created to commemorate April 25th, marks a dramatic shift in the city’s perception. The image of a naked worker attempting to flee the overwhelming force of the steel plant embodies a growing sense of estrangement. These two works not only highlight the contrast between a time of optimism and disillusionment, but also trace the transformation of artistic language—from an expression of industrial utopia to a denunciation of a harsh and unsustainable reality.

We return to the belly of the Concattedrale, where a video-installation revives the space’s original cinematic vocation. A series of images portrays the very room we are in, duplicating it, just before the setup of SOTTOSOPRA. The words come from Michele Perfetti’s text, published in 1965, the same year Taranto’s full steel production cycle began. At this moment, a young soprano from the Giovanni Paisiello Conservatory sings La Violetera. The famous piece, also cited by Perfetti, is the iconic leitmotif from Charlie Chaplin’s silent film City Lights (1931), that compares the different living conditions of a millionaire and a vagabond. The lively tones of the zarzuela deliberately clash with the sounds of protests, political slogans from the factory workers, and the rumble of colossal machines summoned by the stories entrusted to us by the documents, functioning in the context as a form of counter-sublimation.

SOTTOSOPRA is not just a journey through an upside-down world, but a quest for an inverted perspective, ignited by the awe of uncovering what is revealed through excavation. It evokes the archaeological method, valuing remnants that give rise to complex visions of living worlds, rewriting the past within the present. In this way, it becomes a form of subversive thinking, emerging from materials that challenge critical exclusion and the erasure of Taranto’s scattered contemporary art heritage.

COMETARIO: a Dot-to-Dot Constellation

The meeting point is the open space overlooking the Mar Grande, in front of the unmistakably fascist Palazzo del Governo. A blue flag signals the gathering. It depicts a comet, its trail drawn in a style reminiscent of children’s dot-to-dot puzzles, where connecting the dots unveils a hidden figure. “The dream is a lost object surrounded by pits where things lie eternally immersed—wrote the poet Paul Valéry, and we suspect these words refer to the history of the city of Taranto’s dream curse.” These are the first words spoken by performer, sound artist, and poet Gaia Ginevra Giorgi as she reads from a small note. Her warm and constant voice, shaped by the art of vocal expression, signals the beginning of a journey filled with dreams and curses. Thus begins COMETARIO, the performative urban excursion created for Post Disaster Rooftops EP05 by Extragarbo, a collective made up of Giorgi, Edoardo Lazzari—curator and researcher in the performing arts—and Cosimo Ferrigolo, set designer and researcher working at the intersection of architecture and urban design. Each member brings a unique research approach, yet together they serve as champions of urban crossings, excavations, and collusions. In the past, they have trained in the labyrinthine “calli” of Venice, their chosen city, and in Rome, where they recently crafted exercises in awe within the urban fabric of Piazza Vittorio, in search of a mythical Pavilion of Wonders.

Here in Taranto, the city of the Two Seas, Ferrigolo, Giorgi, and Lazzari have spent both short and extended periods of time. They operate this way, by positioning themselves physically within the city, engaging with its dynamics, absorbing its social moods, studying its blueprints, and giving even the subtlest stories the depth of a narration. They spark chance encounters, turning them into elective affinities. One contact leads to another—a world of intersections with children, elders, and shopkeepers, all flowing within the rhythm of negotiations.

With COMETARIO, they invite us to trace the path of a real and imagined journey, one aimed at unraveling and disrupting the regular grid of Taranto Nuova’s urban fabric, stretching east of the Swing Bridge toward Borgo Umbertino, with its wide streets, residential blocks, and public palaces. Their goal is to penetrate this compact pattern, developed under the shadow of housing demand driven by industrial needs since the late nineteenth century. To break through its rigid orthogonality of surveillance and control, they create a mythopoetic ethnography, attuned to the dreams of the people they’ve encountered.

The walking trajectory unfolds “in a constellation” of points-dots. The true starting point lies in the story of the “curse”: an enchantment that prevents the citizens of Taranto from dreaming. The nightmares—ecological, social, and economic—represent the last line of defense against the spell that has smothered the city’s dreams. Here, the dream—“shape-shifting creatures,” as they describe it—becomes a nocturnal flow of images, sounds, sensations, and thoughts: a brain activity inhabiting other intensities. But it is also the capacity to imagine a collective future through desired actions. The dramaturgical process of intertwining the stories they met, spread out within the urban map, is the tactic Extragarbo uses to suggest intensive modifications of space. Thus, the process reveals how the close connection between forms of life and the “capacity to aspire” (as Arjun Appadurai might describe it) is tied to social models, cultural practices, personal coefficients, and spatial organizations—all related to power systems.

In immersing ourselves in the urban life of Taranto, Gaia Ginevra Giorgi, our guide, acts as a mobile and discursive vector, guiding us through a tapestry of words and footsteps. Her voice delivers a blend of the inhabitants’ dreams, skillfully interwoven by the artists: “electric blue lights at the tips of fingers, sleepwalkers, seers, mysterious fluids, a hen pecking at a fingertip, corridors leading nowhere, rooms we cannot escape from, phosphorescent dust rising through the air…” The texts that lead us intricately weave together legends, sensory details, temporal distortions, and inverted cause-and-effect, all within a language rich with both factual reality and magical invention. Beneath it, one can hear anecdotes, critical notes, poetic phrases, hidden desires, and silenced speech bubbling up. It begins with the shared understanding that every step on the cobblestones and asphalt we walk on today once rested on soft, marshy, shaded, and elastic land. Echoing Crispiani’s Paludofobia, we find ourselves plunged in an epistemological space that embraces a vibrant world as the result of a collaborative interplay between living and non-living elements. Giorgi shares with us a story passed down through generations, where it was advised to place a glass of water by the bed to invite dreams. By magnetizing the fragments of the soul, water is believed to have the power to disperse ghosts, thus liberating dreams. Taranto, sited by two seas, emerges as the perfect place where dreams can thrive.

COMETARIO is conceived as an intentional composition of stops that connects the neighborhood to dreams and the impossibility of dreaming, using them as tools for creating memories, echoes, and revealing forms of resistance, as well as the frustrations of everyday life. As we continue walking, a city, both suspended and embodied, begins to unfold in a form of reversed magical realism: here, it is not extraordinary events described in realistic tones, but rather the everyday that emerges with the exceptional quality of a vision—much like the moment one recognizes the luminous tail of a comet in the sky.

Along Leogrande’s promenade by the seafront, with its view of the harbor bay, a path descends into the urbanized Mediterranean scrub, leading to the “little beach at the edge of the dream.” Here, dreams are etched as “secret codes” (for intimate encounters) on marble benches or stored in semi-clandestine spaces within seaside shacks, designed for psychedelic transitions—improvised refuges that urban decorum would prefer to push to the periphery of sight. A steep staircase is ascended, but not before a comet—like the one stylized on the flag—is sprayed in yellow on a stencil. A mark of presence on the city’s skin, reflecting our passage, is renewed at each stop of the Major Stars, the “dots” on the celestial map that shape the chapters of our story.

We begin walking again through the uniformity of buildings, until we come to a pause: “Often, we dream when we stop, and we stop where there is space, and there is space where there is a threshold between one thing and another.” Lazzari awaits us in an interstitial space, a small clearing where lush, untamed vegetation flourishes. He greets us with beach chairs and an assortment of homemade lemonade, some even fermented. This green void in the city stands as a vacant space that resists the forces of real estate speculation, where spontaneous biodiversity is embraced in all its variety. Giorgi tells us that the Guerrilla Gardening group, in their gatherings, has hosted “collective dream sessions” to create forms of resistance against the lack of green spaces. And like them, we too can carry out our counter-curse, launching seed bombs with the desire to reforest the city. After passing the Fadini market, we encounter the story of Pablo, an eight-year-old boy from Lanzarote who no longer dreams. He hopes that a stranger like him—perhaps Saint Cataldo, protector of foreigners, as suggested by Extragarbo—will restore the forest world the city has denied him. Pablo no longer dreams, but instead imagines worlds during the day, framed by the square window of his room. The window appears through the glass walls of a supermarket parking lot, overlooking a bustling street. We are given numbers that correspond to chairs, from which, once seated, we can observe our “viewing angle,” an urban drive-in without cars. As we share roasted almonds, we watch the scene unfold: the film of the pastry shop, the outdated shoe store, the electronics shop, and a strange half-human, half-animal figure with the head of a parrot wandering by in a worker’s jumpsuit. Suddenly, The Cuckoo by Benjamin Britten plays at full volume, and the already blurred line between reality and imagination collapses into one. We head toward the “Wonderful Agitation,” a place of reversed traces. In the small square Piazza Messapia, a birdhouse holds colored chalks: anyone can create their own star map on the pavement, as if the sky had fallen to the earth. The asphalt transforms into a canvas for drawings and writings by homeless people, children, participants, and passersby. The maps, as critical cartography has shown us, are no longer simply two-dimensional plans; we can envision them as embodied desires and inventions of memory. While we draw our stars and write our thoughts on the ground, from the cabin of a car, we hear half-spoken words from fairy tales, blows and skips, cries of victory, lullabies, arguments, and animal sounds… This is the audio of Giochi di fanciulli (1970) by Giorgio Pressburger, an authorial radiodrama without a plot, capturing the voices of 40 children from an elementary school in Turin as they play freely in a recording studio. Through this layering, the noises of the square blend into the echo of words and sound liberated by the fantasy of children’s imagination.

Further along, the stop at the Taranto necropolis on Via Marche brings Pablo’s dream to life from the depths of time. Beneath our feet, we spot ancient burials with square rock blocks, while a very sweet music fills the air. We listen to Sogno di una cosa by the musical project La Festa delle Rane, where air organ, musical saw, the sound of branches, and gem recordings blend with children’s voices singing the story of a river, immersed in suspended nature. Giorgi suggests recognizing in the river’s outlet the source of “citri”—Taranto’s typical phenomenon of freshwater springs rising from the seabed. The water here seems to breathe its own rhythm, drawing liquid circles. The archaeological site becomes a dive into Taranto’s geological memory, still vibrant within its aquifers.

The path to this point has been marked also by the Minor Stars: focal points on brief flashes in the urban sky. Giorgi uncovers them by whispering, like a game of telephone. These are moments of intimacy among COMETARIO’s participants, a way of embracing knowledge that shifts as it passes from mouth-ear-mouth. They trigger new forms of visibility, like pricks of attention. This is true for the intersection of Via Duca di Genova, the only curved street in the New City layout; the “radiator buildings” with their ribbed infrastructure; the precarious tympanum in the Church of San Francesco da Paolo; the broken clock at the Military Arsenal; and the Invisible Palace, “the one that disappears when you look at it”—a critical irony highlighting the gap between buildings.

Near the end of the journey, we pass through a sports center where the caretaker opens a private door, granting us access to a park that seemed inaccessible. We then reach a residential complex overlooking the Mar Grande. Our gaze drifts across the vast expanse of water, as the setting sun bathes everything in golden light, accompanied by a soft breeze. Our guide invites us to observe the phenomenon of the citri, “which takes us back to when Taranto was a forest,” allowing “mollusks, invertebrates, fish, children, young people, strangers, dreams, nightmares, temporary communities, and all other soft creatures to find the best habitat to proliferate.” Giorgi encourages us to spot a dolphin. It seems these creatures have the habit of descending to the sea floor as they fall asleep, only to rise as soon as they touch the bottom: “just like in dreams.” The flag in this communal space is now yellow, like the spray used for stencils. But now, the comet has turned into a dolphin.While enjoying red wine and chickpea omelette, we are handed the published map of COMETARIO (Ziczic, 2025), which contains the words we’ve heard—a reservoir of knowledge to be reactivated through new perceptions and rhythms. The vibrant, childlike design by Extragarbo with Juta promises a final revelation: the constellation of “dots,” when connected, forms a comet or a dolphin, aligning with the Major and Minor Stars, the map of the city we’ve just explored. It’s a magical suggestion to trace endless figures and tell countless stories. Through the collective act of listening and walking, Extragarbo’s COMETARIO offers a poetic-political rewriting of Taranto: an anti-monumental city experience, blending tangible forces, affective dimensions, rhythmic intensities, urban sounds, struggles, and allusions. The blend of prohibitions, microclimates, gaps, taboos, and social urges, envisioned in a dreamlike yet critical alternative, serves as a force to reshape our understanding of space and time, fostering new connections, perceptions, and possibilities for social transformation.