The “I” that is a “We”

Women who are one woman and this one woman who is all these women: a journey at the heart of Italian feminist art

Curated by Raffaella Perna and Marco Scotini, the exhibition The Unexpected Subject proposes for the first time a wide-ranging investigation and a precise reconstruction of the relationship between visual arts and feminist movement in Italy, identifying in 1978 the catalyst year of all energies in play (not only in Italy). Here a sentimental review, followed by a short interview with the curators of the exhibition.

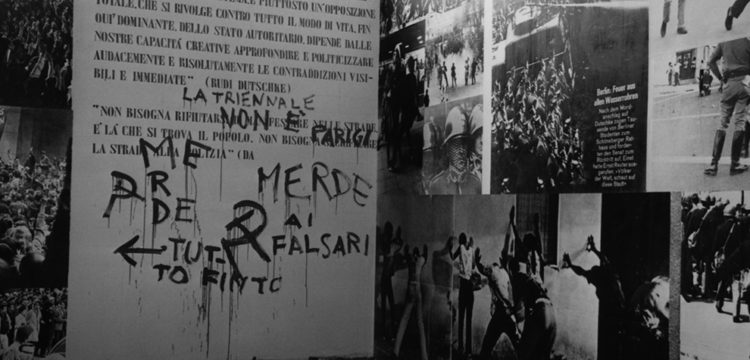

This is a path that speaks of unprecedented languages and gestures, thus of liberation of a specific category of bodies, namely women. We can call these languages and gestures “unprecedented” because the historical period in question is the 70s. Before that time, those women—women like me, were either housewives or mothers, or anyway objectified, and considered to be worth not even half of their male counterparts, at least in Italy (already the fact that they were destined to have a counterpart either in a male or in religious commitment disturbs me enough). So these women artists are by necessity frontrunners. Nobody before them could ever do what they did in the way they did it. Many of the presented works are unsophisticated and intuitive in form.

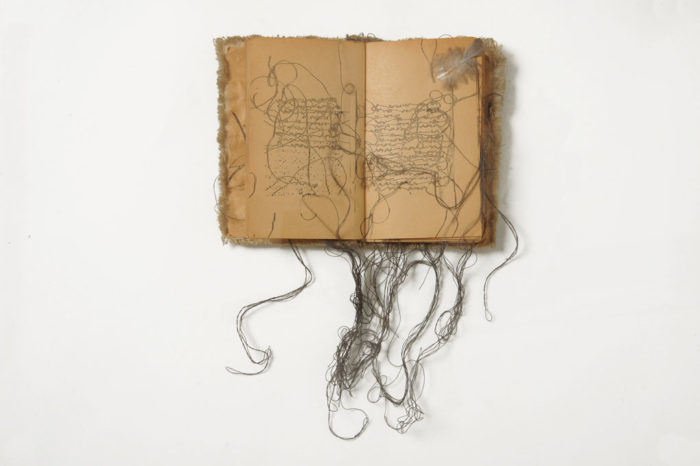

Maria Lai, Libro cucito E, 1979. Private collection, Milan.

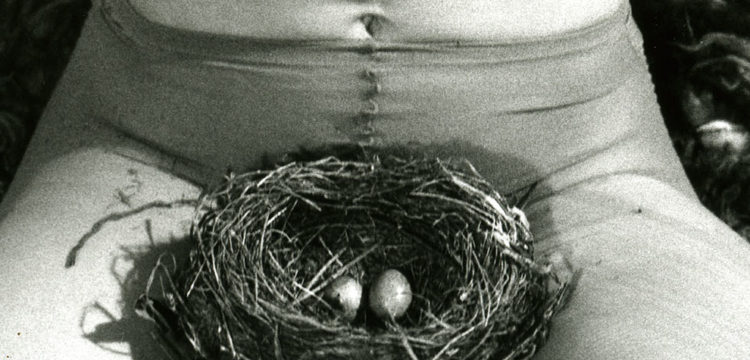

This woman is a woman that writes, prints, takes notes—takes the note and breaks it—sings, shouts, whispers, takes the technique and makes it her own, composes, answers to the world around her—because she feels and listens (in Italian they’d both be sente, both for sentiment and the act of listening), she opens up, cuts up, glues, deletes, and changes her mind. She’s not the woman or the artist of the “I” but she is the artist of the “You.” She draws patterns, gesticulates, counts, she juxtaposes and overlaps languages; she diversifies. She comes in and out the image, she stitches and unstitches; by necessity she strikes. She can be both symbolical and allegorical, starting off in close contact to her body and to the household, she leaves it without abandoning it, nor denying it. She doesn’t break but transforms. She comments while composing. It’s about what’s familiar more than what belongs to the Family (intended as in the conventional sense of biological family).

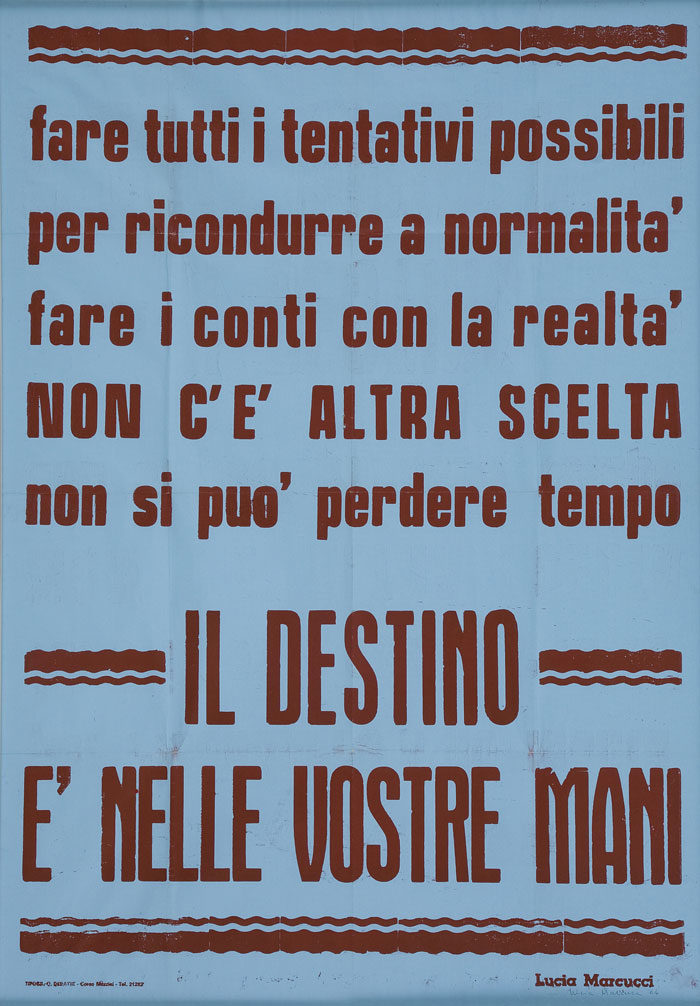

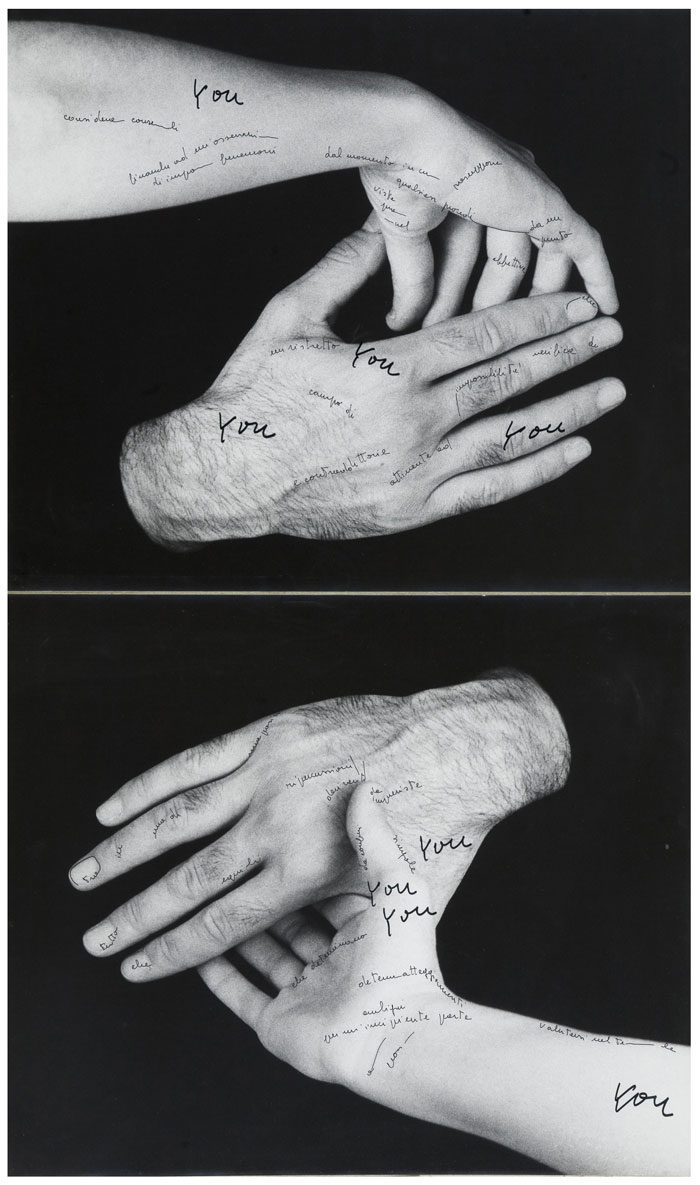

Lucia Marcucci, Il destino è nelle vostre mani, 1964. Private Collection. Courtesy the artist and Frittelli Arte Contemporanea, Firenze.

Anecdote: once I was talking to a philosopher and I used the word “hope.” He told me—well, I wouldn’t call it hope, it sounds religious to me. Here I have found Lucia Marcucci using the expression “the virus of hope” and rejecting perfection. Both things made me think of this anecdote, in terms of linguistic and symbolic adjustment to the patriarchal culture. It made me think about Agnes Varda saying “I tried to be a happy feminist, but I was really angry” and our right to be, indeed angry, to use the word “hope” and to reject imposed models of perfection. Our words can be as nervous to counterpart all the imposed silences there have been, and still are enough for a genealogy. And we can’t waste time, because we need to claim the fact that our destiny should be in our hands. This is what all these women were telling me, as if it was one single woman speaking, as if it was me.

Ketty La Rocca, Le mie parole e tu?, 1971. Courtesy The Ketty La Rocca Estate and Frittelli Arte Contemporanea, Firenze.

So, the women. These women were saying things I said myself, they were making gestures I have done, their language was echoing mine to the point I thought—this means I am not alone, this means I am one of many, this means that this “I” is a “we.” And in this historical moment this we is important, is contemporary and relevant especially in the art world. This we stands against the endless “I” of the male genius, and of conceptual art, where the idea becomes commodity and power. Meanwhile, this woman that is one and many is alphabetizing, creating a new taxonomy, using her body, protesting from home to get out in the world. She shows what’s normatively concealed. This woman does what we all do. She sends letters. In Italian, mailing is called corrispondenza, which literally means correspondence. She creates, does, mails “correspondence:” always putting the “I” in relation to others. Meanwhile, in the same period, the feminists are meeting in the city, opening their spaces and taking the streets. Yes, they are meeting, and what do they do? They listen to each other in the name of freedom of expression, they do not just protest, but they employ consciousness to transform it into autonomy. This exhibition made me realize that this was the first time that this process could ever be recorded. And these women who are one woman, as this one woman who is all these women, are giving birth to a discourse. They are producing literally from scratch a discourse that puts them in relation to the world, for the first time ever, not only in relation to man.

Mater means both mother and matter in latin. As this woman becomes matter, all these women are structurally changing matters.

Clemen Parrocchetti, Lamento del sesso, 1974. Ph. Antonio Maniscalco. Courtesy Archivio Clemen Parrocchetti, Cantalupo Ligure (AL).

Giulia Crispiani: I don’t know whether this was the intention when following such an anthological approach in curating this wide-ranging investigation on the relationship between visual arts and feminist movement in Italy, identifying in 1978 the catalyst year of all energies in play. Let’s start from the title, I know it comes from Carla Lonzi’s Let’s Spit on Hegel (1974) but why and how did you chose this specific definition?

Marco Scotini: Of course all of this was intentional. It is essential however to start with two main considerations, both of which were born out of a realization of our contemporaneity, which is a far cry from the seventies and the birth of the feminist movement. The urgency and purpose of this inquiry has been to regain a fundamental genealogy of social conditions in a contemporary world which now includes a constitutive plurality of sexual identities beyond the binary male-female, and a decentralization of what is “human” in the post-Anthropocene. It’s undeniable that the feminist movement of the seventies was the first radical break with the universalist claim of the uncontested and hegemonic subject of history: the male. But where were we to find such a genealogy? In Italy the relationship between art and feminism is rarely documented. This pushed us to fill this baffling and anti-historical void we have inherited from the official narratives. This is why we used an archaeological method to try to map out a radical, recalcitrant, and incomplete patchwork of histories. We had to begin this chapter with Carla Lonzi, with the radicalism of Sputiamo su Hegel (Let’s spit on Hegel) and with the equally radical, although never direct, relationship she establishes between art and female subjectivity. The Unexpected Subject is a subject that categorically refuses any past political, cultural, or social principle that has been naturalized. And it is “unexpected” precisely because it isn’t ratified by any dialectic which could have pit the servant against the master until eventually they implicitly and definitively swap roles. This, then, was the feminist subject of the seventies. A total, unedited openness and freedom of thought, action, behavior, and speech.

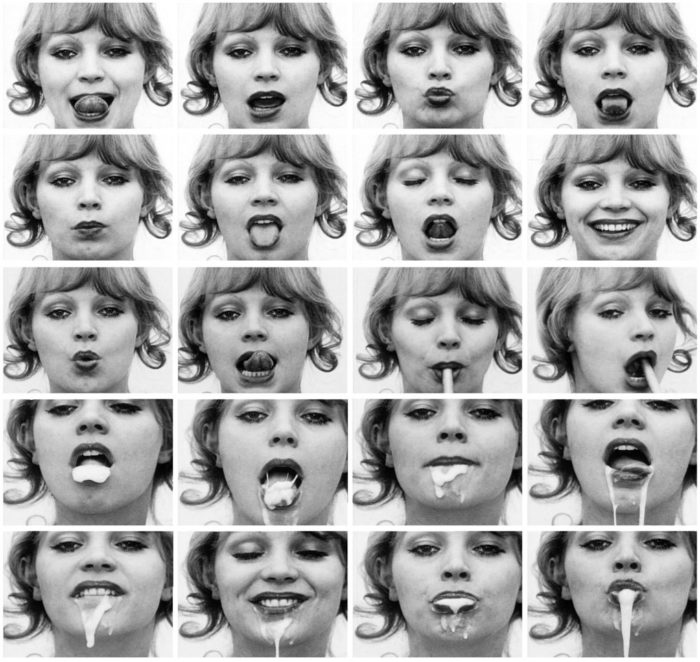

Natalia LL, Consumer Art, 1972-1975. Collezione La Gaia, Busca (CN).

What would be the contemporary evolution of this definition today? Are “we” still an unexpected subject?

MS: I don’t think the openness I referred to earlier can ever really be closed in the conventional sense. This would entail a redefinition of the matter in essentialist terms of identity, gender, and “new nature.” Subjects born from the seventies onward disavow, or should disavow, any codified and prescriptive determination of class, race, gender, and hierarchy. They should always try to belong to a ceaseless and permanent process of mutation towards a multiplicity. Nowadays the literature tends to identify feminist figures as eccentric characters (Teresa de Lauretis), fractured identities (Donna Haraway), and nomads (Rosi Braidotti), among others. After all this effort it wouldn’t make sense to relocate within the art field. I believe that from this perspective the reclamation of the personal sphere as political, the blurring of boundaries, the act of making everything accessible and situated, tied to the body and our own uniqueness, has been the great legacy of feminism. So why should we claim that art should be separated from the rest?

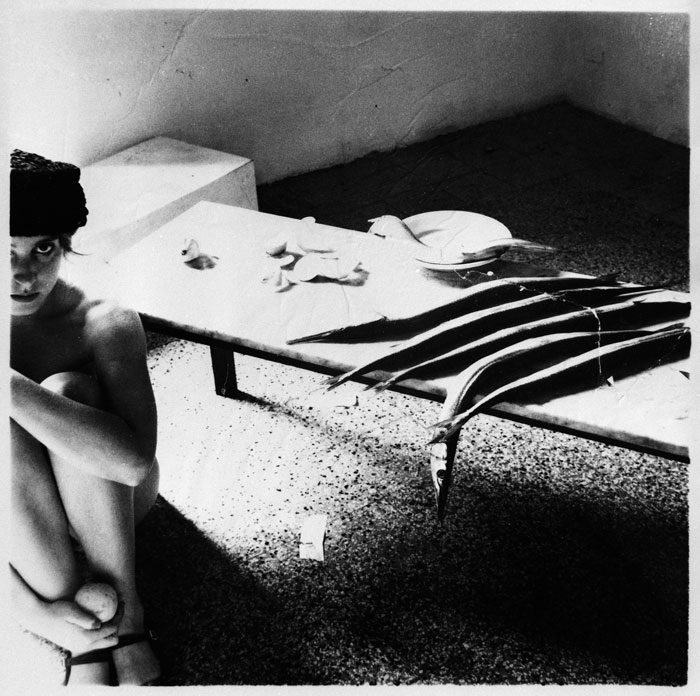

Francesca Woodman, Fish Calendar – 6 days, 1977. Collezione La Gaia, Busca (CN).

As mentioned above, when I was walking through the exhibition I was feeling very grateful towards these bodies, as many aspects of our current language, behavior and freedom that we take for granted today were actually initiated back then. So I would be curious to know more about this historical, almost scientific approach, could you elaborate on that? What can the radical experience of these women still teach us today?

MS: As I said, what you call a historical-scientific approach is actually a genealogical method, originated from Foucault. If you trace anything back to its roots you never find the same origins. Rather, one finds discontinuity and unexplored territories. In fact, even in the case of Italian feminism it would be more accurate to discuss an assortment of different “feminisms” rather than one unified narrative, and this is addressed in the exhibition. Carla Lonzi and the “auto-coscienza” (consciousness-raising) have been one of the main drives of this process, along with the Padova school on the wages for houseworks with Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Silvia Federici, and Leopoldina Fortunati. And still another center was Luisa Murano, Lia Cigarini, and Lea Melandri’s, which was tied to female self-representation in a more psychoanalytical matrix. The show at FM gives an account of all these expressions in a linguistic and visual form. Therefore, giving those movements from that period in our history a new life has created a counterweight to contemporary rhetoric, which seeks to channel and unify.

Libera Mazzoleni, Il bacio, 1977. Courtesy the artist and Frittelli arte contemporanea, Firenze. © Libera Mazzoleni.

In this sense, I have to think of the Guerrilla Girls’ posters and broad body of work on the relationship between women, art and museums. I see this trend is finally slowly changing, yet I would like to know whether your choice to display the “front runners” of a specific scene and historical moment was more of a tribute or a way to counter this well-known tendency in contemporary art?

Raffaella Perna: Yes, I also believe this tendency to be shifting, but in a less radical and profound way than one might expect at first glance. Feminine presence in temporary exhibitions has increased, but the acquisition of pieces by women in Italian museums are still lacking. Even academically, there’s still a lot of work to be done in Italy. The show at Frigoriferi Milanesi, as I intended it, constitutes a contribution to this deficit: it was conceived as a chronicle which would deepen and give value to the stories of these women artists, stories that are still partly unexplored. And yes, of course it exists in juxtaposition to the canonical narrative of Italian art in the seventies, one which focuses almost exclusively on male figures.

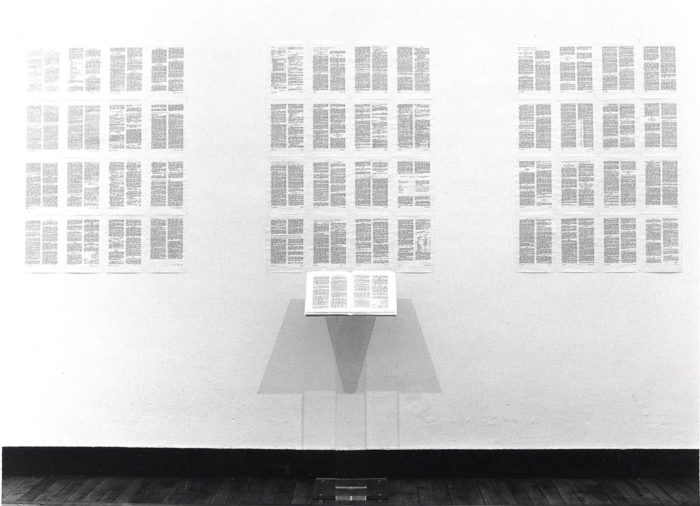

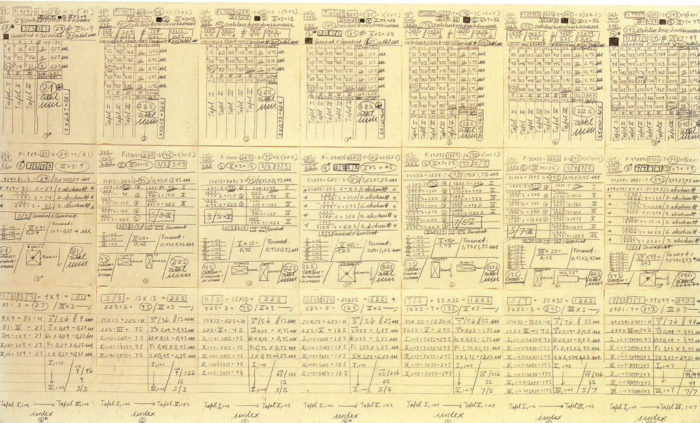

Irma Blank, Trascrizioni, Documento ABCD, 1977. Courtesy the artist and P420, Bologna.

I have noticed that Dior is the sponsor of the exhibition. What kind of woman, does Dior portrait? I mean, this is of course a general tendency today, that necessarily puts in relation various forms of radical thought and capital. Is this an indifferent or an instrumental relationship?

RP: The exhibition was sponsored by Dior because Maria Grazia Chiuri, their art director, is a woman that identifies with the thoughts developed by feminism. Her ideas are expressed not only through her collections but also through her passionate and genuine support of Italian women artists. In the past few years she has initiated important collaborations with different artists and photographers, many of whom were women who had participated in the feminist movement in the seventies. I met her during one of my lectures on Ketty La Rocca, an artist we both love. In this case it is not an instrumental relationship, rather a path of personal and professional growth, which pushes her to promote projects she believes in.

Hanne Darboven, Untitled, 1972-73. Courtesy Collezione La Gaia, Busca (CN).

Also, back in the days feminist art functioned as an echo chamber for a much wider movement. In this specific historical moment, in light of—for instance—events like the Verona’s congress of families (I visited the show one week after that and my mind was unavoidably going back there from time to time) and our government view on gender politics and such, how do you see these practices as counter-effect to the current misogynist tendencies? When you started conceiving the exhibition did you see as an active device for a counter discourse?

RP: The current political situation in our country (Italy) is disastrous. The Verona congress and the Pillon decree are extremely serious matters. But if you ask me the exhibition wasn’t born to counter the government’s current position. Of course it does present itself as a radical alternative to misogynist rhetoric, which is quickly gaining ground in contemporary political discourse. Male chauvinism is a lot more pervasive however, and exists outside right wing circles. Often it can be found within unbearably paternalistic men who speak for women, claiming to be authorities on their lives and histories. Both the exhibition and my decade-long career as a curator and art historian have been shaped by feminism. For me the discovery of feminism catalyzed a deep existential change that revealed itself in my work and my research. This is why I decided to study the history of these women artists in the seventies which had been relegated to the margins of critical discourse. On this journey I was able to count on the help of the artists themselves and of people like Simone Frittelli, without which today’s exhibition would not have been possible.

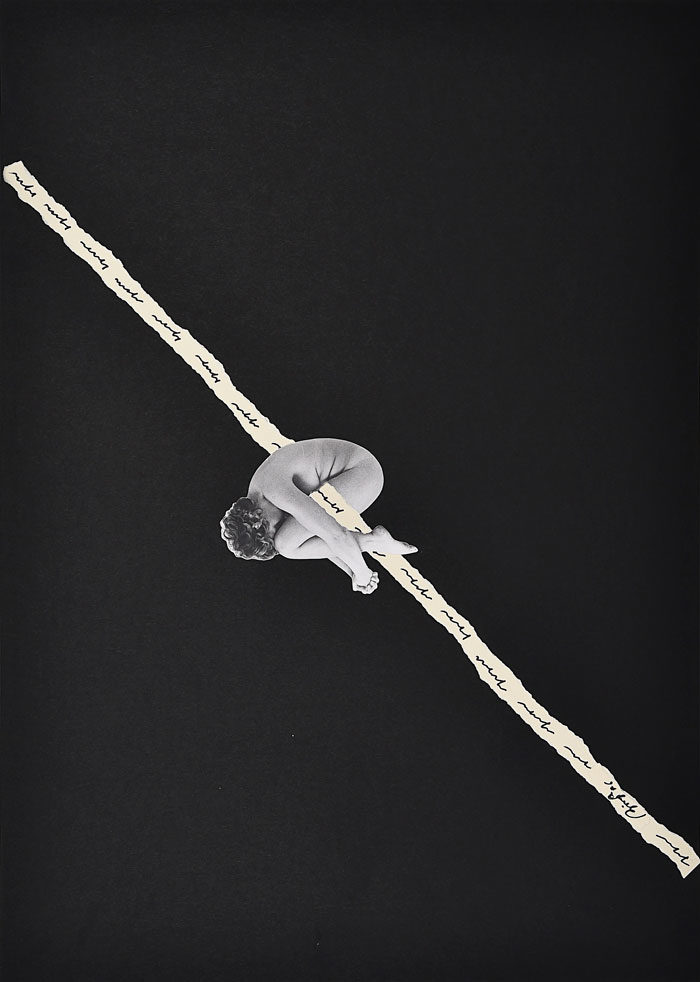

Tomaso Binga, Scrittura arrampicata diagonale, 1976. Private collection. Ph. Andrea Chemelli. Courtesy the artist and Frittelli arte contemporanea, Firenze.

The role of women in the art world has always been subsidiary, yet has contributed to influence the broader discourse. How do you think we can exit the common rhetoric on feminism of the unexpected and the subsidiary?

RP: Not by waiting for someone else to recognize our value. We should state it ourselves, on a daily basis, through our life choices, our careers, or our artistic and curatorial practice. As women we should also recognize the authority and value of other women first of all.

MS: I don’t think ‘subsidiary’ and ‘unexpected’ are synonymous, nor do I think that a rhetoric of the unexpected subject could exist. The term can certainly be co-opted by the culture industry and the market; therefore it becomes neutralized and politically neutered. Nowadays this is the common fate of many forms of subversion. What remains intact is the substance of the term: we must constantly unlearn norms, rules, and codes. The value in the unexpected subject isn’t its ability to acquire power, rather to rebuke it wholly. The unexpected subject doesn’t fight for inclusion or to regain position, it undermines any patriarchal or Neo-liberal condition and means of production that begin to show signs of hegemony. It isn’t an easy task, but the goal is to let “unexpected” possibilities for life blossom in the places where they are currently being denied. In essence, women are not unexpected subjects by nature or destiny. One must become an unexpected subject.