That Back Has Overflowed

The rest is grass, booths, some swings and stale light

This text was written for the publication produced to accompany the exhibition entitled Indicio (Intimation), as part of the programming of the Photomuseum in Zarautz for the months of July and August 2023. The exhibition is curated by Jose Ramón Almondarain and brings together some thirty works from the MV Collection of Fernando Garate and Estrella Gómara.

Elongated moving shadows of varying widths are being projected on the wall in the living room. They are coming from the street, cast by the neighbours’ garden. Such shadows keep rocking on a wall above the couch I am slouched on, wedged in between its wrinkles. They are entering through that rectangular, overly small window, making me feel as if I am on a boat that it is pulling out and drifting. And, as always, I’ll probably get dizzy. The humidity of this island, its excessive wind and the knowledge that there are seagulls, contributes to this feeling. There are seagulls, foxes, bats, squirrels, worms and crows.

A year ago, when I lived further south, I came across these animals daily. I used to see bats in summer, like racing palpitations over Blackheath’s pond. I followed the foxes with my bike, for they don’t get scared that way, and I can keep an eye on their ghostly leaps from up close. Slimy, smug worms curled and twisted upon themselves. They could be clearly seen on the narrow granite paths winding through the parks. The rest is grass, booths, some swings and stale light.

London’s light pollution means that we can look at hundreds of colours across the same landscape. During the 2020 pandemic, we got used to going around a small artificial meadow, scurrying about every day to witness the sunset, as I recall my great-grandfather used to do. In the sky, I like any colour, especially pink if it approaches orange, with a red circle inside, as well as the almost black dark blue that becomes purple next to petrol stations or near football stadiums in port areas, with small construction bulbs inserted, erect and parallel like pins, in between the very thick dark clouds.

But the world already had tinted lights before the light pollution of cities progressed. Stained glass, or stained glass windows, seemingly comes from the desert. According to Pliny the Elder, it was the Phoenicians who discovered several multicoloured beads on their extinguished bonfire from the night before, and they thought it was a miracle. Later, many glass objects were produced in the Alexandria region, while Syria and Mesopotamia spread this industry throughout the Mediterranean. We often identify the technique of leaded glass with Gothic churches, in which it experienced a great boom as a mystical material. The development of buttresses, pinnacles, vaults and ribbing helped to open the iconic large windows of which we are thinking. In them, the skills of the artisan glassmaker merged with those of the master painter, including a wide range of colours, as well as a feeling of volume, perspective and numerous representations. Christian stained glass windows produce an image that is double and simultaneous. The halo of light, a symbol of God, floods these gathering spaces of celebration; and at the same time, biblical representations are outlined on the glazed surfaces through which this light is cast. They are something akin to radiating paint.

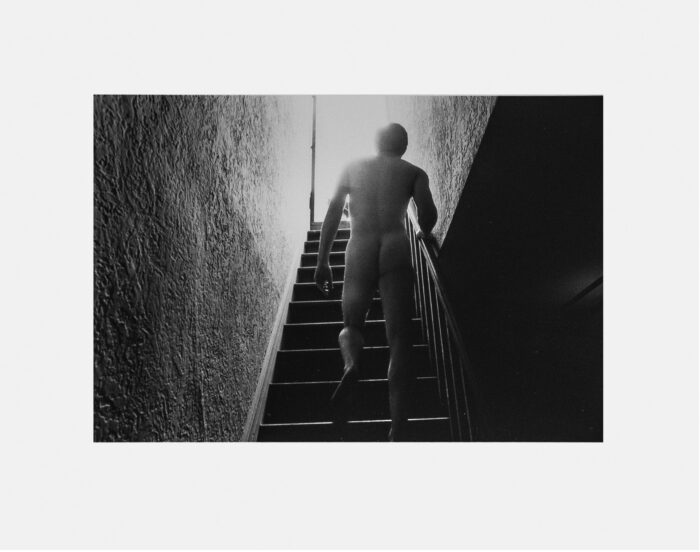

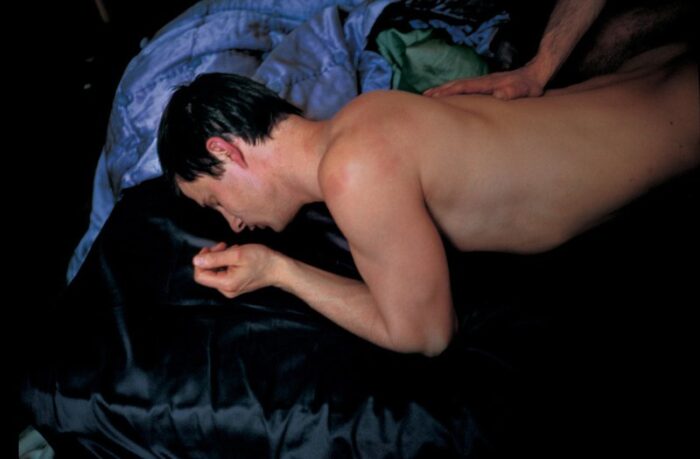

I looked at the images of this exhibition and in them recognised wind, rooms and stumbling. How one corner leads to another, empty spaces, fortifications, mist and loins of horses, men and bulls. One back contains several floods. The body of a man rises upwards. We look at it in the backlight, as a silhouette from behind. Our brain has been designed to constantly generate the categories of figure/background. Within each set, it selects a stimulus and separates it; in most cases, the background can be imagined as continuous, behind the figure; this figure appears to be closer to the person looking at it, while the figure behind it has no precise location.

Much pictorial tradition has reproduced and intensified this visual mechanism, organising the composition of paintings, altarpieces and murals by means of visual hierarchies. Nonetheless, our brain sometimes malfunctions, becomes disordered, collapses and fails to complete this function. Or rather, what surrounds us does not admit being divided and the figure/background distinction becomes ambiguous and difficult. Our perception then develops into something disordered; it gets overwhelmed and changes. At that instant, we invent a more confusing relationship with reality in which the environment is not remote, but the perceiver’s body merges with it to produce a strong relationship between our gestures and movement, our disorientations and what appears: we take a step and something grows; we bend down and the floor turns; we close one eye and the wall becomes uneven; we stretch out our arms and the room shrinks; we try to talk and the light flickers.

Following on the path of the mystical or religious experience, the entertainment industry has incorporated our bodily function into its conception, precisely managing the biochemical surges of adrenaline, dopamine, endorphin, etc., and sporadically generating the appropriate emotions for each experience. Sensitive rhythms are organised in an exact script from which complex ideas can be derived, and it is repetitive and competent, capable of being reinterpreted many times. Like the chorus of a catchy song or a political slogan, the emotional articulations to which our organism adheres during such spectacular experiences are strongly addictive.

Research in statistical mechanics claims that, while the actions of an isolated individual are impossible to predict, when it comes to groups, these behave like a fluid, and collective reactions can be guessed by means of the same formulas that reveal the movement of dunes, whirlwinds and other air currents. We function together through identification and resonances, collective oscillation in sensitive reaction to the environment. Movement is telepathic, and it makes me think of how to make sculptures depending on where you are, and of how fear spreads to us through the vertebrae.

Cinema achieves one of the most immediate expressions of this fusion of spectator and medium. In front of a screen, we observe identifications between ourselves and what is presented, even physically. Such a process of involvement in the matrix of the event is known as “suturing”, and it is achieved by aligning the point of view of the camera with that of the spectator, imagining that he or she enters the field of narration, that he or she joins in with those who act and their changing points of view. In so doing, cinema doubles psychological projection for imaginary projection.

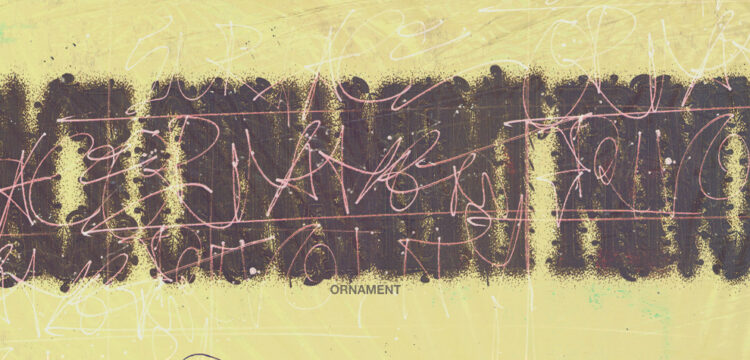

Many of us have worked on the excisions of the projected image, attempting to reveal and exaggerate the hypnotic mechanisms of films. In order to do this, we change the speed, use slow motion, intercut, include shocks, intensify silences, intersperse opacity, interrupt, etc. Until giving the video a hypnotic, almost catatonic rhythm, and these videos emerge flickering. Their stuttering allows us to distinguish the constituent parts of the medium while watching the screening. Our body as spectator becomes another component, recognising its reflections, shadows, the shock of the eye, muscular tension, and the materiality of celluloid, as added elements in the ritual that each screen produces.

Someone I knew once described the feeling of riding a Harley motorcycle as “speeding, full of enthusiasm, towards a wall”. Coming across a wall head-on is usually already a shock and a disappointment, because the street you were thinking of going down is blocked, or perhaps you have been locked up. By looking at it, it gives us a feeling of blockage. I remember waking up as a child in the middle of the night because of a nightmare in which I had been spinning around a lot. Getting up disoriented, walking by sliding my hands along the walls of my room, trying to locate the doorknob without knowing where the door was and imagining, terrified, that the entire room was a wall.

Walls are intrinsically opaque, hard and inaccessible, but we also come across their more fragile or permeable imitations, with curtains and cracked walls, through whose gaps we were able to insert fingers or little sticks that would help us to pierce that surface, draw back the veil and look at what is outside, on the other side. They promise a behind. Once again, to achieve a backlight.

The Gothic artefact of dual narration and divergent stimuli has been multiplied a thousand times over. Bright environments bathe us, forever merging the backgrounds with the figures. The symbol lies behind the artifice and the representations exist traversed. To follow is to flicker.