Subverting Structures

Núria Güell taught me how to hack the apparatus of power from the inside

“The tactics of appropriation have been co-opted. Illegal action has become advertisement. Protest has become cliché. Revolt has become passé…Having accepted these failures to some degree, we can now attempt to define a parasitic tactical response. We need to invent a practice that allows invisible subversion.”—Nathan M. Martin, Parasitic Media, 2008.

I first encountered Núria Güell’s artwork during a visit to the MACBA Museum in Barcelona two years ago: in a room designed to resemble a modest living room, self-portraits of an unknown couple adorned the walls covered with old, faded wallpaper. Captured in low resolution by a compact camera from the early 2000s, these images portrayed simple moments of everyday life. The room, shrouded in darkness, imparted a peculiar feeling as if I had stepped into the intimate space of a private home left vacant during a holiday.

Next to these images, on the adjacent wall were a series of letters, each covered by a thin plexiglas surface. Each letter showcased a distinctive handwriting, with some solely bearing text and adorned with squiggles and improvised designs representing flowers or hearts, like those exchanged at school between teenagers in love. The sole source of illumination was a television installed on the wall, placed directly in front of the sofa. It projected a looped trailer resembling a wedding film, accompanied by a Latin American song: but as the images and videos flowed, with an amateurish, rudimentary editing, what appeared to be the story of a romantic relationship, soon became apparent as the story that led to a divorce.

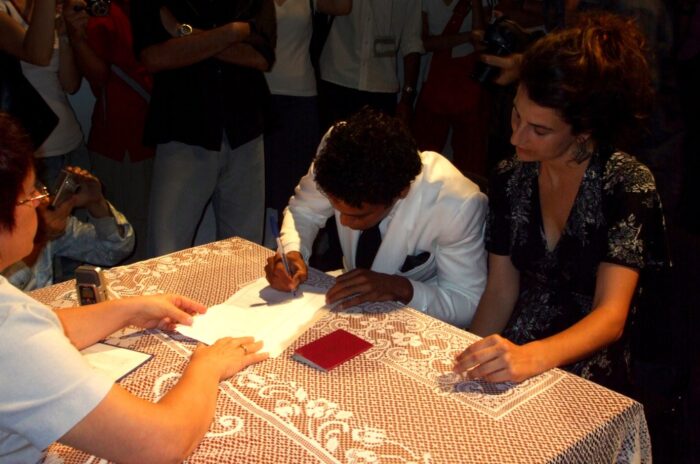

It was 2013 when Spanish artist Núria Güell, sitting in a room of a museum, signed divorce papers with her Cuban husband Yordanis, married just four years earlier. Surrounded by visitors filming the scene with mobile phones and video cameras, Güell prepares to put on the paper her final signature to complete the procedure, which is followed by thunderous applause and celebration.

The moment of divorce marks the completion of a project called Ayuda Humanitaria, a long-term performance that Güell started in Cuba in 2008, while attending a course with artist Tania Bruguera at the Cátedra Arte de Conducta de La Habana. Walking the crowded streets of the city, Güell observed how many young Cuban boys and girls offered themselves as private guides to accompany tourists—often much older than themselves—and try to get into their good graces, hoping to marry them and obtain the necessary documents to finally leave the country.

Embracing her privileged status as a European woman, Güell made a bold decision to extend an offer of marriage to the man who crafted the most compelling and passionate letter for her, handing out cards in La Habana with the inscription: “Chica española se ofrece como esposa al cubano que le escriba la carta de amor más bonita del mundo” (Spanish girl offers herself as a wife to the Cuban who writes her the most beautiful love letter in the world), she then outlined the terms and conditions in twelve rules, emphasizing the subject’s complete dedication to the realization of the project, the commitment to promptly sign a divorce upon receiving the documents for Spanish citizenship and an equal division of proceeds if the artwork are acquired by a museum institution.

Deciding not to choose her future husband based on personal criteria, the artist engaged a group of young prostitutes to read and evaluate the received letters and discuss among themselves to determine the romantic one. This unconventional request added a layer of intrigue to the project, as captured in a frame of the video where one of the girls remarked: “He talks of everything but love?’’

Güell’s practice is often made tangible in the drafting, compilation, and exchange of documents: through a printed guide, the sending of love letters, in the sealing of a contract. It is often said that the written word is what really counts: it takes time to be written, imprinted on the surface, and often accompanied by a signature. For the artist, it is a serious commitment to take part in the project.

Stacks of documents composed of the artist’s personal research, are also often written by lawyers: for many of her performances, Güell collaborates with figures who daily deal with the law and the mechanisms that regulate society: a consistent part of her work is to find loopholes in the law, to put under the spotlight what she calls the “hypocrisies of state ideology’’, by exploring the concept of hegemonic morality. Through her body of works, she aims to criticize the narrative that the state portrays about itself as perpetual morally justified, by simply unraveling through performance as device, the social contract that citizens are bound to, even though they may never have formally endorsed it.

Her approach has been defined by Anna W. Fisher as a practice of “parasitic resistance”, taking a cue for the name, and broadening the debate in the field of artistic practices, from the author of Parasitic Media, Nathan M. Martin, in a contemporaneity whereby activism is over-used by brands and guerrilla has become a marketing strategy, the only path to resistance—after acknowledging these failures—is through the pursuit of a parasitic tactical response.

“It is possible to consider living parasites to be the most substantial group of activists in our world. Parasites make up the majority of species on Earth. Parasites can survive as animals, including flatworms, insects, and crustaceans, as well as protozoa, plants, fungi, viruses, and bacteria.”

Güell is aware of the progressive loss of meaning of the term “resistance” in the contemporary art scene, and it is from this consideration that she has decided to focus on the concept of ambiguity inherent in this term. Like the parasites described by Fisher, those who adopt resistance practices can only feed off the system in which they live. For Güell, too, it is an act intertwined with the system it opposes, because it is rooted in the awareness that resistance cannot erase itself or alienate itself from the system it is without it, it could not develop.

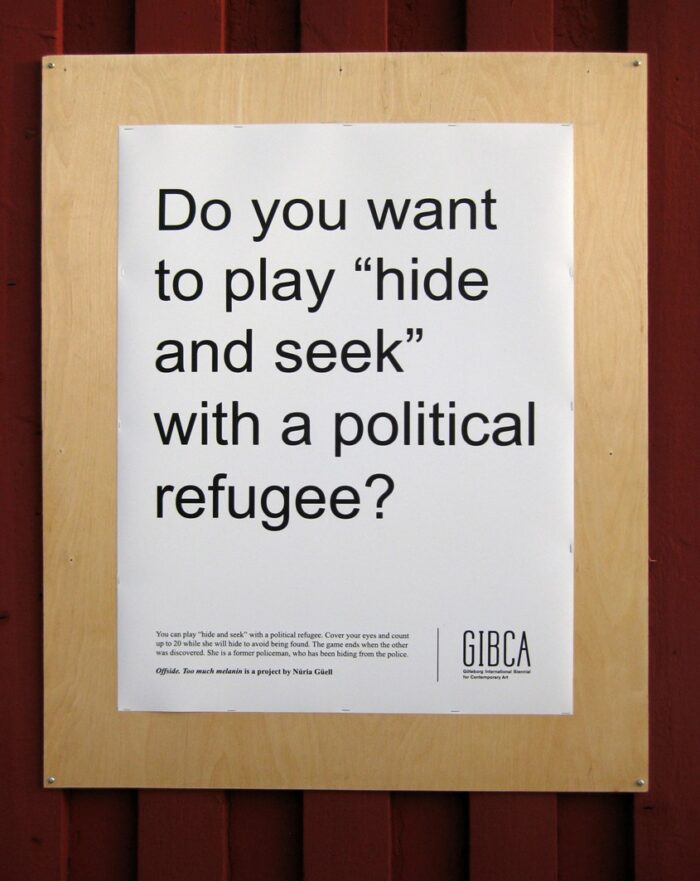

Love letters or irreverent games considered apparently childish are some of the weapons Güell adopts to subvert the much crueler games conducted by the state apparatuses of power: in 2013, the Swedish government promoted the REVA project, which consisted of rewarding police officers for every illegal immigrant detected and caught. This sadistic game increased the number of identifications especially towards those who had “too much melanin” in their skin. The artist, invited in that same year to participate at the Göteborg Biennial, replicated quite the same game promoted by the government: she asked to the curatorial board to hire Maria—an illegal immigrant of Kosovar origin—as a performer, to play hide-and-seek with visitors for the whole duration of the biennial. Like in the game “police and thieves”, Maria hid, trying not to be found. As in Ayuda Humanitaria, the visitors were introduced to the game through a call to action: in this case, posters beared the inscription: “Do you want to play hide and seek with a political refugee?’’

Maria hid along the city’s harbor area, while amused visitors hunted her. Thanks to the employment contract concluded with the Göteborg Biennial, Maria was later able to apply for a residence permit to live legally in Sweden, and finally stop hiding from the police. The sadistic twist of fate was that before emigrating from Kosovo because of the war, Maria worked as a police officer specialized in missing and women trafficking.

One could say that Güell’s practice constantly seeks a boundless confrontation, to enquiry the ethical and moral conventions for which we have stopped asking questions, for they have been completely incorporated into society. This is why the role of information, the method applied and the people involved are at the heart of her work: it means making us ask ourselves one day, out of the blue, if we can decide to be Stateless by Choice (2015–16), whether it is possible not to be citizens of any nation, or to cancel the right determined by blood to belong to a certain state. Güell does so by pushing this reflection to the point of absurdity, asking the Spanish state to open a procedure to renounce her Spanish nationality. After months of waiting, the artist was denied the request, since, according to the government, the loss of nationality is contemplated only as a punishment imposed by the state, and in no case the possibility that a person can renounce her nationality independently. In a frame collected by the body cam the artist was wearing during the interview, the astonishment of the policewoman shines through, albeit from a pixelated face, saying: “We are here just to make you national, not to get out.”

Núria Güell’s tactics are often characterized by studying and introducing herself into the intricate mechanisms of an institution, be it public or private, and then dissecting and overturning them in order to bring out new alternative models. In doing so, it is important that Güell does not limits herself to the abstract and theoretical level: with her performances she intends to intervene directly in people’s lives, and then give the public a method, taking care to meticulously explain the process undertaken, to encourage critical understanding and independent thinking: on her website, and at the site of her performances the artist often provides a guide, an how-to for replicating, for disseminating and making people aware of a condition to which we are subjected but of which we are unaware, because it is naturally assimilated within the social structure.

Almost every one of her works is accompanied by a vlog, footage usually shot by youtubers to tell a first-person account of a lived experience, like a stream of consciousness in which they try to put order, to the succession of events, trying to dissect them. Together with the documents, which accompany her performances are the only testimony that the artist shows us inside a space: a 57-minute-long video posted on YouTube contains the entire talk from Rambo (2016), a workshop organized by Güell and given by a war veteran critical towards the army, in a New York City schoolhouse to children as young as 14 years old, a year before they were indoctrinated by the conspicuous enlistment campaign for U.S. Army, often making use of war games, such as Call of Duty, to make the narrative compelling.

Also the museum-institution that hosts her performances has an important role, which does not appear as a mere container, but as the artistic medium itself: Güell manipulates it as if it was made of clay, expands it to explore its tension, pulls it again and again until it reaches its maximum point before breaking, through a semantic process capable of questioning and discussing its logic, and its contradictions, (ab)using the privilege given by artistic practice. The museum institution or gallery is asked to take an often uncomfortable position, to expose itself: it is asked, for example, to hire inmates in the surveillance of the works exhibited in the room, if it were not, that these were all imprisoned for art theft: again, the employment contract entered into by the cultural institution allowed them to leave the prison to go to work for other jobs as well.

Like the spores of the fearsome Cordyceps fungus, a parasite capable of penetrating the brains of its invertebrate hosts, Güell expands to take control, if only temporarily, of museum institutions that too often pretend to forget their role for fear of compromise themselves. Picking up and emphasizing Audre Lorde’s words and bringing them back into the realm of art, according to Anna W. Fisher, it is “only” a matter of dismantling the“master’s house” by using the “master’s tools.”