Spolia and Power

A conversation with Andrea Polichetti

Between sculpture, painting, and installations, Andrea Polichetti’s work is constantly growing. His pieces connect with the past while looking toward the future through materials and techniques that show the complexity of an increasingly layered and unstable present. The cumbersome legacy of a city like Rome, where the artist has always lived, emerges in Polichetti’s research, calling into question the very concept of ruin and, consequently, problematizing the notions of protection and conservation, precisely through the legacies of a past that may not yet be entirely over. Considering his recent and upcoming experience in China, where he has been and will be involved in various exhibition projects, we spoke with the artist about his work, comparing two cultural and social contexts that are not only apparently so distant.

Jacopo De Blasio: The concept of ruin and its reworking recurs in your artistic research. What does this often misleading or elusive notion mean to you?

Andrea Polichetti: A ruin is a decayed, incomplete structure that can be freely crossed, an experience of exploration in motion, of physical involvement and discovery. In my work, the conflict between man, nature, and time is also intrinsic to the concept of ruin.

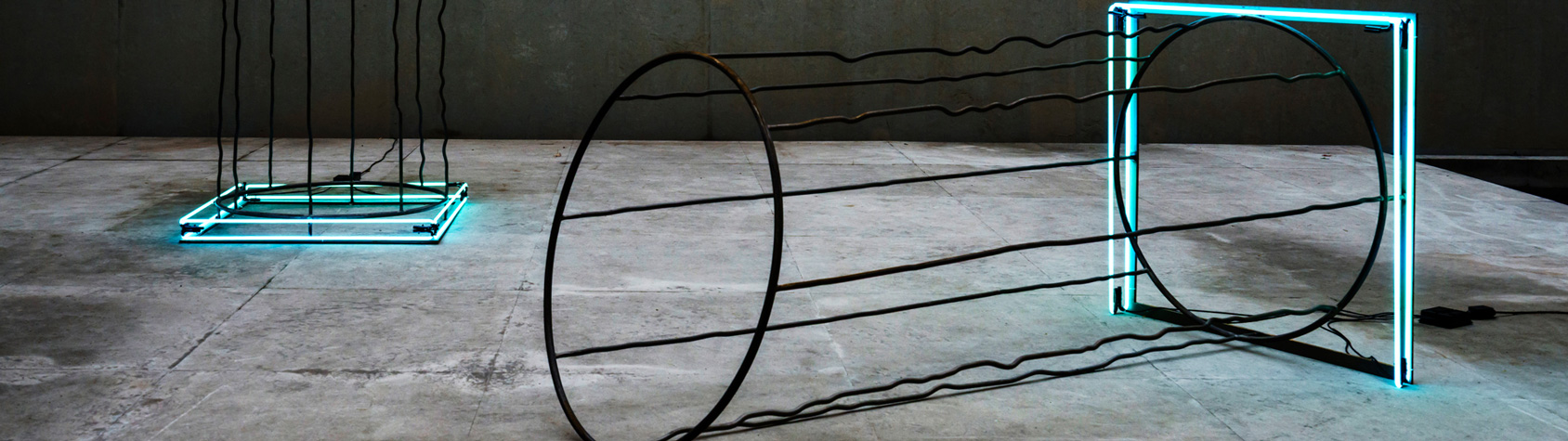

The architectural residues of my sculptures are objects to be contemplated, through their relationship with space and the experimentation with industrial materials, such as neon and metals, which record the decay caused by the passage of time through their corrosion and deterioration.

In my most recent research, I am analyzing the idea of spolia, its interaction with the landscape, and its relationship with the expression of power. In this case, sculptural groups will interact with the space, attributing to it those connotations of discovery and reflection that can be experienced by passing through them with the body.

In my most recent research, I am analyzing the idea of spolia, its interaction with the landscape, and its relationship with the expression of power. In this case, sculptural groups will interact with the space, giving it that sense of discovery or reflection to be experienced physically.

How do you think contemporary art can contribute to redefining conservation practices for monuments and places of historical interest in the urban fabric?

It would be appropriate for cultural companies to reinvest part of their revenues in order to promote dialogue between the contemporary art system and the museum system, whether or not it is related to antiquity and classical art.

By making knowledge more accessible, communities engaged in dialogue and effective critical thinking would develop. This would eliminate the self-referential or classist exclusionary attitude that alienates the general public from contemporary art.

With my work, I would like to activate archaeological sites with a public program that is not exclusively focused on visual art, but also on the world of music and entertainment.

One example could be Folgore, a work created as part of the FuoriFestival in Spoleto. I turned the icon of the fulgur conditium upside down and reinterpreted it, recontextualizing it to express the sacredness of a perimeter—an element typical of Roman rituals—in this case, the dancefloor.

Could you explain what classism means to you in relation to art, not just contemporary?

Today, it is almost impossible for someone who does not come from the upper class to climb the social ladder, especially when working in the cultural industry. Art, in particular, remains a family affair, where too often the social background and its codes are more important than the work itself.

In more recent times, significant steps have certainly been taken to make language less exclusive. At the same time, I think it would be wise to adopt a linguistic register and communication styles that are closer to non-initiates in order to bring them closer to art.

Even what is considered mere entertainment for the general public still attracts people’s attention and curiosity towards certain places or topics, contributing in part to reducing progressive cultural impoverishment.

Returning to the concepts of protection and ruin, considering your recent and upcoming experience in China, what are the main differences you have noticed in this regard?

I was in residence at Rabornova Art City thanks to an invitation from curator Carlo Maria Rossi, founder and director of No-name Studio in Shanghai. In 2026, I will be in residence in Shenzhen at the invitation of Kaiho Yu, co-founder of Collecta. On this occasion, I will have the opportunity to conduct field research to explore the concept of archaeology in a city that is still under construction.

I don’t have the knowledge to make an in-depth analysis, but speaking from a simple feeling, I would say that the idea of ruin is less pronounced than in the West. Constant functional protection, in fact, makes these places similar to amusement parks. Here too, there is a lack of critical thinking, which is often absent even in the West. At the same time, however, they are truly accessible places with a social function. They generate services for citizens and places dedicated to their personal growth.

What role does the exhibition space or the place where you make your works play in your research?

For me, interaction with the surrounding space is fundamental. I made individual works or exhibitions that take shape precisely from the exhibition space. In UpsideDown, I doubled and overturned a plinth from the Museum of Roman Ships in Nemi, emptying it of its functionality and activating it as a small non-monument through the use of materials. For me, it is important to ensure that the works interact, activate, and integrate with the space so that I can make it my own and share it with the public.

In Nanjing, where I will have a solo exhibition in the Tunnel Space of the Beiqiu Museum, in spring 2026, I will implement an operation of this type: the works will illuminate the space, inhabiting it and thus altering it, excluding the museum’s technical equipment. This idea led to the development of my first functional sculptures, Light / Consumption. These are neon tubes shaped like the iron rods in the works Architettura #, which mimic the disintegration suffered over time by architectural archaeological finds. They are luminous devices adaptable to scenarios that could be defined as post-apocalyptic, as they embody disintegration in their design, serving as a warning of the same fate that awaits the contemporary spaces they inhabit.

So do you believe your works are context generated or, on the contrary, do they generate the context?

I think they can be situated in the middle. This is because the genesis of the work certainly starts from space, and then modifies it in favor of the experience of enjoyment.

And if these works were destroyed precisely because of the effects of atmospheric agents and space, what would you do?

Right now, I have some iron sculptures that are degraded, and I was thinking of carrying out some conservation work, but I gave up on the idea. It would not have made sense to do any cosmetic work. These works will be carefully cleaned when they are moved to a new exhibition space.

Does this topic relate in any way to the works you will be exhibiting in Nanjing?

There will be iron and neon sculptures, which will change over time, and new paintings on glass. The latter are the result of research on signs undertaken in Shanghai this year. I would like them to interact with the condensation generated by the water due to the very high humidity in the exhibition space. In this way, the work and the space merge according to an anti-conservative approach.

Staying on the subject of your upcoming exhibition in China, how did you think to develop the concept for the exhibition?

At the Beiqiu Museum of Contemporary Art, I will exhibit works conceived as true statements of my research. I imagine these objects, functional or otherwise, as ruins of the future.

The various works recount an intertwining between my place of origin and my host location. These are not univocal works, precisely because interaction with the surrounding environment leaves open the possibility of multiple interpretations of the works themselves. In this way, the force of nature that inevitably traverses time, despite human intervention, is made explicit. The exhibition will be accompanied by a critical conversation between Riccardo Chesti, who currently lives and works in Hong Kong, and Francesco Lee, who works both in Italy and Mainland China as art historian and curator.

Regardless of the concepts behind the various exhibitions, what excites me is the energy of the people I am working with in China. These collaborations make it possible to formalize different lines of research and find answers that, through experimentation, may one day be truly useful to society.