Reconcile with the Closet

Terre Thaemlitz’s “Reframed Positions” at Halle für Kunst Lüneburg

Reframed Positions is the first multi-venue retrospective by artist, producer, writer, educator, audio remixer, and activist Terre Thaemlitz (*1968, Minnesota, USA) in Europe. It comprises a survey exhibition, talk, multimedia performance, and a concert curated by Lawrence English, Elisa R. Linn and Ann-Kathrin Eickhoff. Reframed Positions takes place across Halle für Kunst Lüneburg e.V., Volksbühne, Berghain Panorama Bar and Callie’s, Berlin. Its first iteration was curated by Lawrence English, and presented at The Substation in Melbourne, Australia, in 2020.

Terre Thaemlitz could be introduced as a musician, visual artist, activist, and educator, but considering his reluctance to succumb to convenient categories, she could be instead introduced as a nihilist in a perpetual state of unbecoming. In an interview with Terre by Terre set up to disclose inquiries regarding her identity, he claims to be a non-essentialist, [1] fluctuating from one category to another according to the context.

As Ludwig Wittgenstein claimed, the meaning of words is made by their use, hence for Thaemlitz certain terms have lost their meaning due to the indoctrination by the heteronormative establishment. For instance, reappropriated offensive terms such as “fag” or “queer” have been absorbed by mainstream language. Thaemlitz prefers to avoid the neutral forms “one” and “they” to address her fluid identity, because gender is never neutral under patriarchy. So how to address Terre Thaemlitz? She certainly prefers confusion over analytical numbness, and thus prefers to alternate the binary form “he/she/he/she” over the third ways “hir”, “zim”, “they”, “them”, that return to the singular identity model. To the question of whether she goes by “he” or “she” Thaemlitz replies—“Yes, I do.”

The awkwardness the interlocutor is confronted with when trying to find the “right” way to address Thaemlitz amuses her, because it is the same awkwardness he experiences when addressing her own identity. Thaemlitz’s universe is deliberately complex and disorienting, as questions around his identity intertwine with artistic ones, triggered by a mix of tactical actions, chance, blatant statements, and perhaps, a search for freedom—as in the freedom to choose who to (not) be each moment. In the written form, however, Thaemlitz prefers to be addressed as “she”, both for practical reasons and to exclude the masculine form in a male-dominated context. Hence, following this wish and for clarity purposes, this is the form that will be used in this text from now on.

Thaemlitz’s survey Reframed Positions at the Halle für Kunst Lüneburg is the second iteration of the exhibition following a project curated by Lawrence English at the Substation in Victoria (Australia) in 2020, that used the same title. Orchestrated by Elisa R. Linn and Ann-Kathrin Eickhoff, Lüneburg’s iteration expanded to include satellite spaces in Berlin, with a series of live events taking place at Callie’s, Roter Salon at Volksbühne, and the Panorama Bar at Berghain during the opening week. For Reframed Positions, the Halle für Kunst Lüneburg turns into a black box, where a set of films, graphic works, acrylic paintings, and documentation of early works is presented.

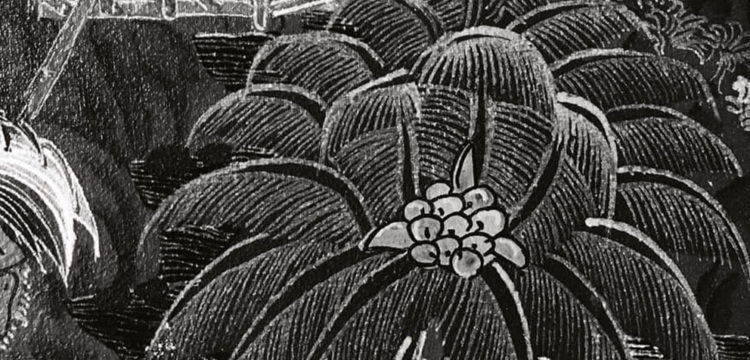

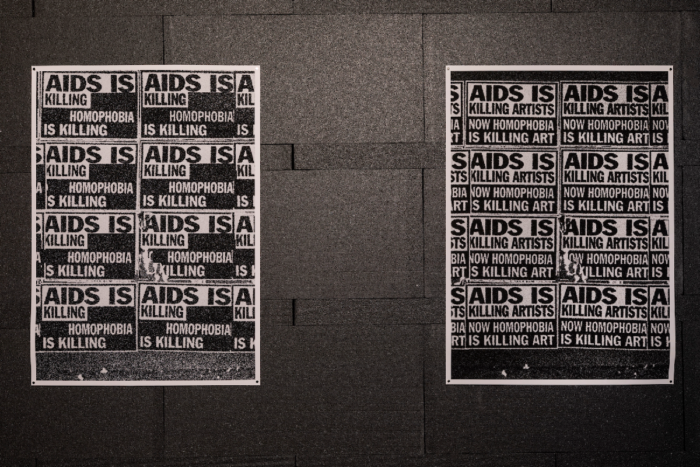

The films Lovebomb (2003), Deproduction (2017) and Interstices (2001) together with Silent Passability (Ride To The Countryside) (1997), run in a loop on three vintage TV tube monitors with headphones. Soulnessless (2012) is projected onto a wall, with its sound permeating the space. The prints and the painting are either hung on the Halle für Kunst’s walls, or pinned on a standing styrofoam wall which divides the space in half. Right in front of the gallery entrance, two digital prints of Fuck Art (2020), depict a reconstructed documentation of “corrective graffiti” on advertising posters by Art Positive.

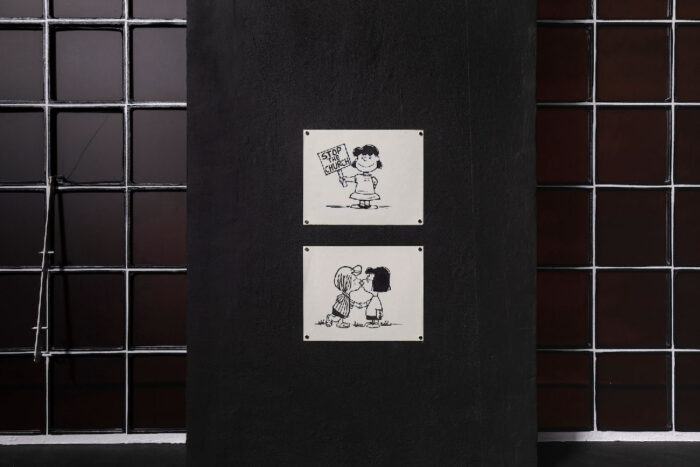

The work is a reminiscence of Thaemlitz’s activist practice, that started during her studies at Cooper Union in the 1980s when Thaemlitz joined groups such as WHAM! and ACT-UP. Also from the same time, the ink on paper prints Happiness is… Choice and Happiness is…Women Loving Women (1989) were originally designed to be printed on T-shirts for the March for Women’s Lives demonstration in Washington D.C.. Now, both prints hang next to Deproduction’s monitor. The prints depict characters from the Peanuts comic strip: Lucie van Pelt with a “Stop the Church” banner printed on the first and Charlie Brown’s inseparable friends Marcie and Peppermint Patty kissing on the latter—a nod to the long-mooted lesbian relationship readers have posited for the characters. When these works were produced, the direct effects of activism turned out to be more satisfying to Thaemlitz than studio-based work that relied on traditional notions of authorship and originality. Thaemlitz tactically continued to fulfill academic requirements in order to continue her activism, following a pragmatic pattern that has shaped her life and work.

Thaemlitz’s tactical approach became further defined upon her arrival in New York City from Missouri, where she garnered a reputation playing house tunes under the monikers DJ Sprinkles, Social Material, K-S.H.E, and others. What started as a coincidental act turned into regular live shows that complemented her non-performative audiovisual practice, allowing her to sustain her non-commercial work. Her immersion in the genre was driven by the solidarity of the denizens of the house and ballroom scene, selflessly supporting a community built by whoever had been abandoned by society, the government, or their families. In Thaemlitz’s words, these house tunes were the “sound to queer spaces for people of colour” until 1992, when the genre was labelled and marketed, and became “fucking elevator and shopping mall music.”

The notion of elevator and shopping mall music—non-music or ghost music—is consciously exploited in Thaemlitz’s ambient soundtracks, which mix speeches, piano melodies, the sound of a needle drop on a vinyl record and other sonic elements abstracted from their original contexts. These tracks are also the departing point for her video works, combining sounds with layers of distorted imagery, chunks of text, shuffling personal narrations, essayistic reflections, political statements and questions about the material scope of immaterial concepts. All these aesthetic resources help to deliver a rough, explicit, dense message, at times overwhelming and hard to process.

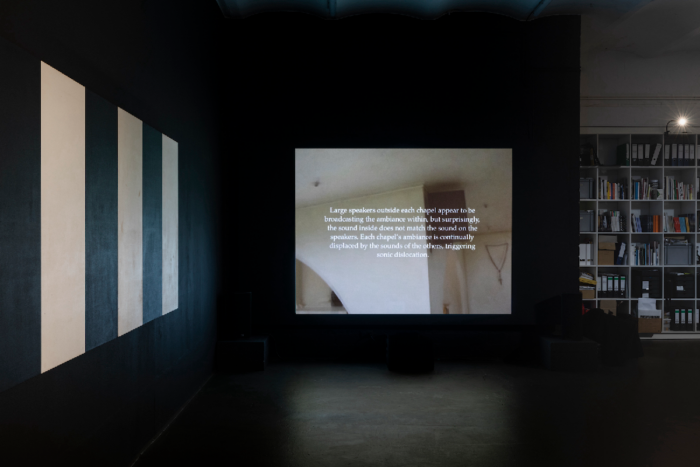

Soulnessless (2012) renegotiates Thaemlitz’s relationship with spirituality—originally defined by hatred. The film intertwines personal memories with accounts of two trips to Davao City in the South Philippines, confronting the paradoxical positioning of religious institutions toward indoctrination and solidarity. The first part of the film discloses Christian symbolic implications of a memory of a Virgin Mary figurine that her mother stored in a phallic wooden box. In Thaemlitz’s eyes, Mary’s gown opened up like a vulva, shifting her perception of Catholic iconography. From that moment onward, the image of Mary holding her baby, or the Pietà became a symbol of the female and male transitioning from one gender to another, coexisting in permanent flux within a single entity. Later in her life, another figurine of a wax Virgin Mary was gifted to her by her grandmother, this time with a penis stuck to it. The gift appeared to Thaemlitz as a revelation of her “gendar”, [2] which confirmed her own grandmother’s nonconformity. These visual epiphanies reflect Thaemlitz’s own identification with MTFTMTF identity [3]

The second part of the film focuses on the material implications of displacement. During those Philippine trips, the artist interviewed some members of the Dominican Sisters of the Trinity about their use of sonic equipment at the church, as well as a group of working migrants. The interest in the latter concerned the legal impediments that doom migrants to furtive lives evading social interactions and surveillance systems, turning them into “bureaucratic ghosts”. The inadequate resources offered by social services make them dependent on the altruistic support often supplied by religious institutions. Through centuries of Christian missions, hegemonic domination and violent actions have coexisted with altruistic acts, much as holy ghosts and bureaucratic ghosts coexist in Thaemlitz’s film. Soulnessless confronts the migrants’ invisibility with the governmental policies that indirectly delegate their care to faith-based institutions, neglecting the vulnerable under the premise of national security.

The film Lovebomb (2003) begins with a set of overlapped 90s Microsoft Windows pop-ups. Each pop-up is placed on top of another and depicts a text block or gay and trans pornographic imagery. They later shifted to a sequence of static images illustrating Radio Freedom, an African National Congress’ broadcast, the oldest liberation radio station in Africa, emerging from the Apartheid era in South Africa. [4]

More appropriated imagery follows: horror film scenes, landscapes, testimonies of nuclear bomb survivors, a self-portrait from high school scribbled over with the word “fag”, and a surreal animation of a nuclear bomb exploding inside a person’s mouth, overlapping with distorted ambient sounds, piano solos, and sound excerpts from Radio Freedom and F.T. Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto. Some parts of the Manifesto appear in text form, as does a report of the brutal lynching in Springfield, Missouri of Horace Duncan and Fred Coker. These two African-American men were murdered three years before the Futurist Manifesto was written, but since Thaemlitz originally thought the lynching year was 1909, in their timeline both events matched, inasmuch as the shared racisms of both the lynch mob and the Futurists.

The Springfield lynching is also depicted in one of the three digital prints aligned vertically on the wall next to the film, as the terrorist attack at the World Trade Center and Aum Shinrikyo’s gas attack on the Tokyo subway. These images are presented in an aesthetic resembling Futurist paintings (Lovebomb 2003). The prints expand the film’s consideration of the countless violent acts carried out by governments and industries, justified through the manipulation of universalist ideas. [5] Lovebomb’s imagery demystifies universal love, by considering it a social construct that divides more than it unifies.

Deproduction (2017) is divided into two chapters. The first layers kaleidoscopic imagery of incest porn with textual narrations of unwanted pregnancies, miscarriages, abortions, in vitro fertilisation, and rape are all happening within the context of the nuclear family. The second chapter depicts a critical essay scrolling up the screen, questioning the expectations and responsibility of parental structures, either by governments and public institutions, or in nuclear family settings. Again, this film points to the neglect of responsibility by state institutions, in contrast with the socially imposed responsibilities of nuclear family structures. The nuclear family format is not necessarily more democratic than many state institutions, and it will keep reifying notions of “human ownership, coerced labor, sexual fascism, gender segregation, and gender exploitation.”

Thaemlitz’s view of love, spirituality, reproduction, invisibility, and gender is nihilistic, since it detaches from any personal beliefs or poetics, focusing on purely material dimension. Her films highlight the infeasibility of moral indoctrination around established universalist ideals. Love for instance is not just an emotion, nor is it universal. It is instead colonial and can act as an ideological device, subject to the cultural variables around it. Pro-family propaganda, or restrictive immigration policies often cover up xenophobia and racism, and distract from making these concepts visible and inspiring populations to combat them. Thaemlitz’s work is motivated by altruistic interactions and the observation of communities, yet she traces a division between the essences of both: the first entails a detachment from an ideological identification, but the latter does not.

Something that the exhibition does not unveil, but crucial to understanding Thaemlitz’s practice, is the way in which she engages with forms of distribution which refuse cooperation with mainstream platforms. For example, Thaemlitz’s works can only be purchased through the artist’s label Comatonse in the form of vinyl records, or SD cards which physically have to travel from Kawasaki—where she resides. This limited availability invokes the “tactics of silence and secrecy” often associated with “the closet”. As Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick points out in Epistemology of the Closet, quoting from D.A. Miller; the oppositions of private/public, inside/outside, subject/object can be established through secrecy.

The sociologist Abigail Saguy notes that “coming out” originally meant acknowledging one’s sexual orientation to oneself and to other people in the context of the Mattachine Society—a precursor organization of contemporary gay rights movements. It did not mean revealing one’s sexuality to the world at large. Thaemlitz similarly declines to open up to mainstream distribution or streaming channels, but her label remains accessible to anyone, though it is to be found primarily by those who know about it already. Thinking back to the times when she found herself coming out, Thaemlitz recalls seeing male truck drivers with wedding rings holding hands in the midwestern American clubs where she would hang out. These were examples of ambiguous queerness from within the closet that stand in contrast to other models of visibility materialized in “coming out” journeys, that won’t guarantee social recognition nor acceptance. Neither is coming out straightforward nor is staying uncomplicated.

“The closet” has undoubtedly been “the defining structure for gay oppression in this century, Sedgwick claims”; the place where sexual and gender “deviants” have been doomed to for centuries to live lives of shameful secrecy. However, Thaemlitz likes to consider secrecy a survival mechanism to navigate the public and private realms according to one’s own criteria. Can the closet also be a metaphorical place for this fluctuation, similar to her mother’s phallic cabinet hosting the Virgin Mary? Is reconciliation with the closet possible?

Thaemlitz embraces the confusion and embarrassment often associated with the closet. [6] Her practice is unapologetic and contradictory, as it triggers a bit of the discomfort departing from itself. Indeed, replying to my own earlier question, how to be addressed is not Thaemlitz’s main concern, besides enjoying the playful awkwardness that this might generate, and despite the complex politics and reflections around her identity. Ultimately, there is indeed no “right” or universalist way to deal with unbecoming. As in Elton John’s or George Michael’s lyrics, Thaemlitz’s deliberate didacticism entails a queer encoding, intended to be disclosed by “those in the know”. Certainly, anyone whose experiences detach from acceptable social behaviors should be in the know and be able to decode Thaemlitz’s “secret” messages. Such deviants, any of us, “will feel spoken to.”

[1] “I reject the notion of my gender identity stemming from something natural, such as an ‘inner essence.’”, Terre interviews Terre, Attempting to answer common points of confusion.

[2] Thaemlitz’s term for the transgender equivalent to “gaydar,” the intuitive ability of a person to assess others’ sexual orientations.

[3] “‘MTF’ means ‘Male to Female’ which refers to people who deviate from an initially male-identified gender identity (conversely, ‘FTM’ means ‘Female to Male’). I tend to list them in an endless cycle, ‘MTFTMTF…,’ because my self-representation is open-ended and goes back and forth.”

[4] Listening to Radio Freedom in Apartheid-era South Africa was a crime carrying a penalty of up to eight years in prison

[5] “[…] the key element of love is the justification of violence”, from Lovebomb, by Terre Thaemlitz, 2003.

[6] “And doing that involves public displays of confusion, shame, embarrassment – a lot of stuff one might also associate with “the closet.” You see how tactics of the closet can still have some use value for us, culturally?”, Reframed Positions, Terre Thaemlitz in conversation with Lawrence English, 2020