Raw Material

What it means to be on this earth as human beings, how we relate to each other and to the world that surrounds us

Zweigstelle Capitain is a temporary and traveling exhibition space conceived by Galerie Gisela Capitain. The first edition will take place in Rome, Italy, with further destinations to follow. The group show Ecco s’incontrano features works by Rome-based artist Isabella Ducrot (born 1931 in Naples), Peruvian artist Ximena Garrido-Lecca (born 1980 in Lima), and Austrian painter Tobias Pils (born 1971 in Linz). The exhibition is accompanied by a program including readings, poetry, music, dance and screenings.

Starting from very different viewpoints, Isabella Ducrot, Tobias Pils and Ximena Garrido-Lecca all share a mutual sense of dealing with raw material as a base for their artistic practice. Albeit with very divergent approaches, all three artists consider the question of what it means to be on this earth as human beings, how we relate to each other and to the world that surrounds us. All three artists convey their complex ideas about life and human relations through a profound engagement with their chosen artistic material. This connection certainly feels close to Italy’s important heritage of the Arte Povera.

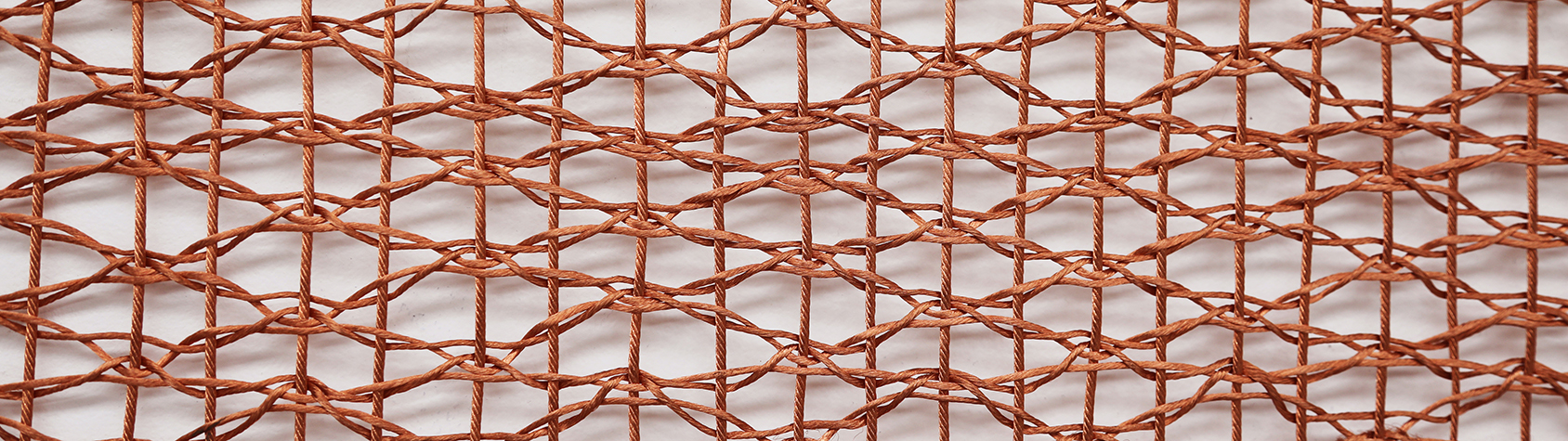

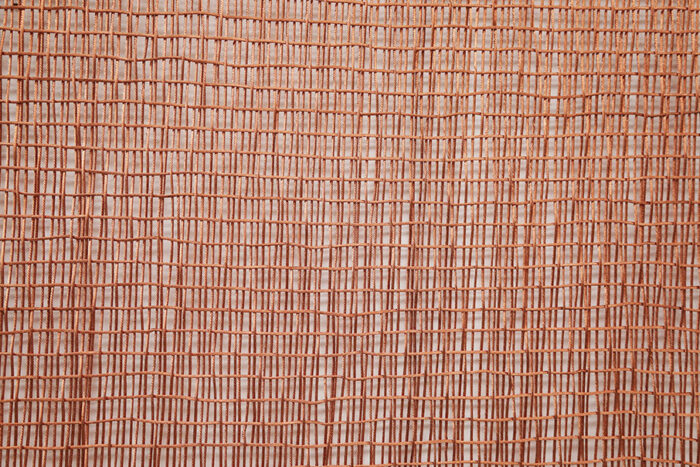

Ximena Garrido-Lecca’s copper works and woven objects address contemporary global concerns of struggles over natural resources, public services and private access for those living on its borders. A recurring theme in Garrido-Lecca’s work is the impact of copper exploitation through opencast mining in the countryside of Perú. According to the logic of the excessive demand for copper in this region, the mines are progressively taking over habitable space, making communities move and radically changing their way of life.

As there is almost no industry in Perú, all the raw material mined in Perú is exported, and then eventually re-imported in its refined and processed form. By bringing the recycled copper back to artisanal practices in Perú, Garrido-Lecca reverts the process of industrialization. In her work, the use of copper functions as a gesture of resistance. We asked her a few questions.

In regards to your research around extractivism and expropriation, what do you think happens to a land that has been “desacralized”? How do you narrate this relational shift—from “men” working with and for the land to exploitation and defacement—through your work?

My principal interest is the shift in our relation with nature and the effects of extractivism on culture and collective memory. Extractivism was born with colonialism, but it has been gradually intensified with capitalism and globalization. The division between nature and culture has created a rupture in our previous notions of the natural world, putting nature in the service of human beings and placing it as a mere object to be exploited. These ideas are in conflict with indigenous Andean cosmology in which nature is intrinsically linked to culture and still venerated through ceremonies and rituals. I am interested in ancient notions of the earth as a living force and revaluing atavist forms of knowledge and perceptions of the world.

Is the material (i.e. copper, silicon and so on) undergoing a similar process? Beside the story that they embody, are your artifacts a way to bring those materials back to the “sacred” realm?

I use copper as a symbol to reflect on extractivism and the impact this material has on the Peruvian economy and its culture. Perú is the second biggest producer of copper and the first exporter to China. Its demand as a conductor for technological appliances makes it the most important natural resource within the Peruvian GDP. By using this material, I intend to raise questions about its contemporary exploitation, the distribution of wealth and the cultural and social impact these practices have in the communities and their environment.

In some works, I create textiles with recycled copper. This gesture is intended to revert this material back to artisanal practices, reclaiming its ritual and cultural use. Copper in Pre-Colombian cultures carried a strong religious and ritual connotation. The act of weaving in Andean culture is intrinsically linked to their social relations and world view, carrying symbolic meaning. For example, in some communities when preparing the loom, they stick the stakes to the ground, asking the earth to receive the textile as a sort of offering. The act of securing its borders is related to reassuring its “growth”, creating a foundation and giving way to the growth of the textile. This sort of foundation is always present in ritual activities. It is considered an articulation or transition that connects one generation to the other. Putting the warps in the loom is like transforming a child into a person and the weft is the spirit of the textile that enters the cloth as the weft advances, creating some sort of being from its head to its toes. In colonial times, the figuration of textile iconography, which carried sacred meaning, was forbidden as part of the ecclesiastic conversion. Despite the absence of this figuration, the structural forms of weaving still carried cultural and social symbology, which in a way became an act of resistance within the colonized communities.

What does it mean to work with the ruins of capitalism and their bulky materiality along with artisanal tradition? How do they meet and how do they diversify?

It is interesting how the idea of accumulation is contrary to some of the fundamental elements of Andean culture and its society, in which regeneration is needed to complete life cycles. For example, the idea of giving is seen as a virtue of strength. There are many different systems and social structures in which they help each member of the community, making sure the “ayllu” and the collective wellbeing is the priority.

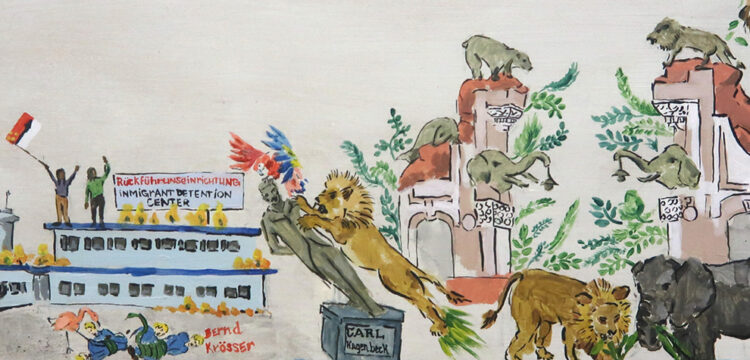

The new forms that surge from the encounter of two different cultures, especially in the context of colonialism, have always taken my attention. I am interested in this place of confrontation, which makes evident the problems that come with the imposition of new systems, and how sometimes the cultural traits that the dominant culture wants to eradicate, end up adapting and resurging in new hybrid forms.

In some of my works, I explore the ideas of regeneration and transmutation by taking the debris of products of commodification, reverting them into cultural artifacts as an act of restoration and resistance. Other times I use industrialized products, to restore them to their natural state or transform them into textiles.

Can you tell us a bit more about the idea of “retribution”?

The concept of reciprocity, in the context of Andean culture, establishes relations of solidarity and wellbeing between all the members of the community, human and non-human. The “ayllu” is conformed by all elements of nature that surrounds them, including non-living forms. There are several rituals of retribution to these elements, and there is always a sense of balance in their relations, interacting with each other through mutual respect and creating a strong bond between them. I think these ideas are very important as they are pretty much opposite to ideas related to extractivism, where the elements of nature are only seen as raw material to be exploited and benefit a small minority.

(Alternating gauze weave with two numerical orders of weft), 2022. Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne.

What is the relation you build with the sites you work with?

I often travel to do field work in different areas. One of my interests is to explore rural areas near the cities where you can observe more clearly the processes of transformation, as they are gradually becoming part of a city. Other times I go specifically to a place to develop a project, trying to connect with communities and understand their way of living. Sometimes this demands a lot of effort as I am not trained as an anthropologist, but I guess the approach is very similar. I try not to interfere or impose my presence too much. At times my approach is more like that of a chronicler, registering what I observe through documentation. I actually have a lot of material I don’t use as part of my work, like interviews, recordings, notes, photographs, etc. Although most of this material is not used, it is a very important part of my research to be able to connect and try to understand the place as much as possible. Normally in these contexts, people think I am an anthropologist. I just tell them… maybe in another life.

ZWEIGSTELLE CAPITAIN

Via dei Volsci 128, 00185 Rome, Italy

Opening: 5 March from 4–8pm

Regular opening time will then be

11am–2pm and 4–7pm and by appointment

PUBLIC PROGRAM

Opening Saturday, March 5, 2022, 4–8 pm

5 pm book launch Isabella Ducrot. Tendernesses with a talk between Emanuele Dattilo and Pavel Rebernik

Friday, March 11, 2022, 6-9 pm

Dance performance Satellite by Chiara Marolla

Saturday, March 26, 2022, 5 pm

Concert by Luke Fowler

Saturday, April 2, 2022, 5 pm

Music performance New Points of View by Igor Caiazza (percussion) with Valentina del Re (violin) and Livia De Romanis (Cello) + Reading by Maddalena Crippa from Isabella Ducrot’s book Women’s Life

Finissage

Thursday, April 14, 2022, 6-9 pm

Music performance Materia Viva by Andrea Mancini and Danielle Di Majo (Saxophones)