Ornithorhynchus Live Somewhere

Between Bauhaus functionality, eco-crisis, and sonic absurdity

As part of the ninth edition of the Parade Électronique project curated by MMT at Teatro Arsenale in Milan, on November 16th the multimedia performance Ornithorhynchus Live Somewhere will take place, a new exploration by Giancarlo Schiaffini (trombone) and Walter Prati (electronics), featuring Gianmarco Canato (bassoon and electronics) and Matilde Sartori (AI software applications). Revisiting the original 1985 work Ornithorhynchus Live in Bauhaus, the performance reimagines the hybrid creature at its center as it moves through contemporary social and technological landscapes. In this version, digital and acoustic elements intertwine, creating a shifting dialogue that situates the Ornithorhynchus within a reflection on globalization, transformation, and ecological adaptation.

In conversation with Walter Prati, who together with Schiaffini composed and performed the original music, we explored the conceptual and technical roots of the project—from their early experiments with the “4i system” in the 1980s to its evolution within Parade Électronique. This new iteration, enriched by the contributions of Canato and Sartori, expands the original dialogue between rationality and absurdity into a contemporary frame, tracing the fluid boundaries between human and non-human, organic and artificial, reality and imagination.

Clara Rodorigo: How did Ornithorhynchus Live Somewhere first come to life in 1985, and what creative or cultural environment shaped its origins? And today, with the involvement of artists such as Gianmarco Canato and Matilde Sartori, how has this hybrid creature—hovering between reality and imagination—evolved?

Walter Prati: Back in 1985, we presented Ornithorhynchus Live in Bauhaus, a theatre-dance performance that intertwined live imagery and music. This multimedia action—what we might now describe as a hybrid project—was shaped by several conceptual threads. We drew parallels between our “unique animal” (the ornithorhynchus, the sole representative of its species) and Gropius’s Bauhaus principle of functionality: that every object must serve a purpose, rather than exist as mere ornament. The biological features of the ornithorhynchus, though borrowing traits from various animals, possess an intrinsic logic—not only within themselves but also in relation to their environment.

We also found resonance with Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, linking the ornithorhynchus’s unpredictability to the rational–irrational duality explored in Bauhaus thought. The performance unfolded as an exploration of geographical, psychological, and social dimensions—relationships, rationality versus irrationality, gendered tension—all framed within a playful reflection on the absurdity of evolution: just as the ornithorhynchus might appear as a zoological anomaly, so too can human behaviour seem absurd when observed from a certain distance.

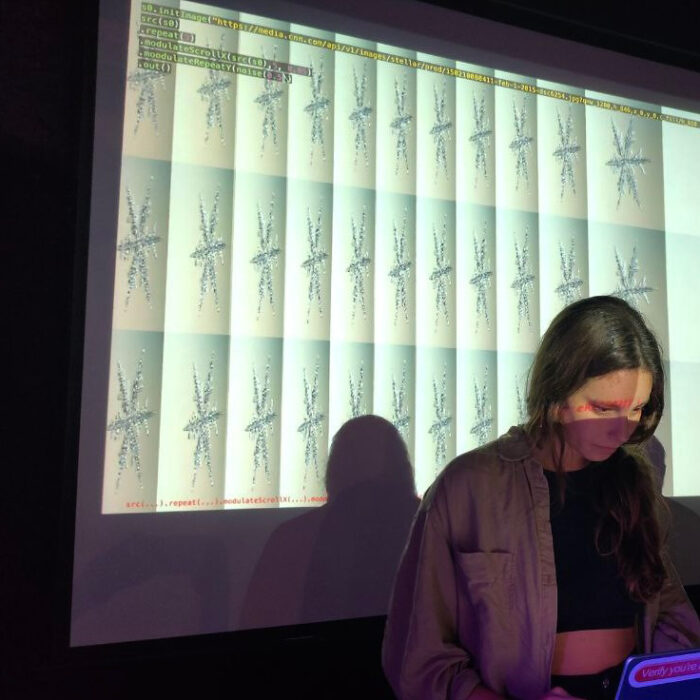

Originally, these dualities—rational and irrational—were expressed through the sound of Schiaffini’s trombone and my double bass. Today, in dialogue with Schiaffini, this voice is joined by Gianmarco Canato’s bassoon. The dancer Anella Todeschini, who once embodied the dual nature of the ornithorhynchus, has now been replaced by Matilde Sartori’s computational interventions: she generates visual components and interactive algorithms that transform the sound in real time.

In essence, the hybrid creature has evolved technologically, becoming a more intricate system of communication—both between the musicians themselves and between the performance and its audience.

Ornithorhynchus lies at the core of the performance—how did this symbolic figure first emerge, and how does it evolve into a metaphor for the human condition today? Does it stand as a model of ecological adaptation, or as a reflection of our inability to transform? In the finale, when it returns to a partially destroyed environment, an ambiguity surfaces: does it embody human resilience, or does it offer a poetic premonition of our environmental destiny?

As in the original 1985 version, Ornithorhynchus Live Somewhere unfolds across five distinct scenes. Yet, unlike its earlier incarnation, today’s Ornithorhynchus faces a world—and a humanity—that have undergone profound transformation. Social relationships have shifted, and despite extraordinary technological progress, our anthropological landscape feels increasingly unstable.

The five scenes of this version—staged without choreography—are Hic ego sum (the introduction of the Ornithorhynchus), Locus ubi vivo (its environment), Cibus vitae (the struggle for survival), Amores mei (the Ornithorhynchus in partnership), and Quis sedem meam evertit? (the destruction of its habitat). Together, they trace the journey of this singularly “fluid” creature navigating a world where devastation ultimately brings its path to an end—a clear parallel to the conditions confronting entire human communities today.

Artists, those who create out of inner necessity rather than market compulsion, act as contemporary shamans. Their work carries omens—manifestations of an expanded perception that invites reflection from those who, caught in the flow of everyday life, may have lost the time to pause and think.

The performance intertwines trombone, bassoon, and electronics, enhanced by generative processes that extend and transform the sonic material. How did you approach the integration between acoustic instruments and technology, and in what ways does this dialogue influence the live listening experience?

The idea of linking different instruments through a “third agent”—a system capable of analyzing and synthesizing the shared components of trombone and bassoon sounds—dates back to the mid-20th century. From the 1950s onward, and especially with the advent of more powerful computers in the 1970s, this concept gradually became technically viable and has continued to evolve ever since.

Today, technological possibilities have expanded significantly: the analysis and synthesis of acoustic sounds are now combined with combinatorial and structural processes, some of which resonate with the logic of machine learning. This makes it possible to design a kind of “sonic script,” while the machines elaborate the narrative in real time, at times making unpredictable choices.

Throughout the performance, the musicians listen closely to this evolving sonic dialogue, responding intuitively as it unfolds—and the audience is invited to do the same. It is this continuous interplay between performers, technology, and listeners that ultimately shapes the experience of the work.

This year marks the ninth edition of Parade Électronique. How has the project evolved over time, and in what ways does it embody MMT’s long-standing engagement with experimental and electronic music? The 2025 theme—Technology and Globalization—connects two defining forces of our time. What led you to approach these subjects through sound, and what kind of dialogue emerged between the diverse aesthetics represented in the programme?

Nine years have passed, yet one element has remained constant: the desire to offer a broad perspective on non-commercial music that uses electronics as a unifying thread—conceptually, aesthetically, and in terms of production. Parade Électronique represents the culmination of 35 years of work devoted to the development and dissemination of electronic music, since the foundation of our association in 1990.

Over time, the festival has featured numerous Italian composers as central protagonists—including Giacomo Manzoni, Gabriele Manca, Giorgio Magnanesi, Sandro Gorli, and Maurizio Pisati—while also fostering strong connections with improvised music and alternative production. Giancarlo Schiaffini and Evan Parker have been key figures throughout these 35 years, and international artists such as Thurston Moore and Robert Wyatt have taken part in MMT Creative Lab productions in the 2000s.

It is precisely this long trajectory that informs this year’s focus on Technology and Globalization. These are terms that, much like “electronic music,” have undergone significant social and cultural shifts over time. In the early 2000s, Technology and Globalization were largely perceived as positive forces—symbols of progress and potential inclusion for large parts of humanity. Yet this was only a possibility, not a certainty. Today, their meanings have become more ambivalent, even troubling: technologies that have escaped human control, transforming into traps rather than tools; communication devices that double as instruments of surveillance. Globalization, meanwhile, has turned into a contested arena for access to the planet’s natural resources.

Within this complex landscape, we continue to champion diversity of thought—a value reflected in the festival’s multiplicity of musical voices. Their coexistence, sometimes dissonant, continues to enrich the dialogue that Parade Électronique seeks to foster year after year.