Nostalgia after the Internet

Morestalgia or what do the Internet and nostalgia have in common?

The neologism “morestalgia” attempts to update the concept of nostalgia after the Internet, investigating and cross-referencing different thematic fields such as memory and affects, migration and homesickness, phenomenology and interface design, history and futurology. It can be also defined as “augmented nostalgia”: a specific kind of homesickness, whose sense of pain is similar to that caused by the feeling of envy, a feeling of lack—self-translated as loss—whose direct reference is experienced by others. Morestalgic human beings are those who have the desire to live an experience they have previously understood as a plausible one but who, instead of recalling it from their own past, supplant it with an immersive navigation experience offered by the Web. With the insertion of this term, artist Riccardo Benassi poses the question: how have social networks and online communities contributed to the unification and normalization of subjective pasts? Can digital empathy become a useful tool to remodel the future rather than creating an alliance around an apparently shared past? In other words, how can we transform a subjective feeling of belonging into a collective future?

Presented by Xing and supported by the Italian Council, Morestalgia is an environment based on sound, text and objects that has as pulsating nucleus a LED screen traversable by the human body and it will take the form of a multimedia and multi-sensory work: a hyperdesigned object. In keeping with Riccardo Benassi’s research pathway, it addresses the theme of displays in living spaces and in urban, infrastructural, and behavioral contexts, starting from an analysis that centers around the human being and its interrelations.

What do you mean by Morestalgia? And how do you position yourself in regards to nostalgia?

Riccardo Benassi: I called morestalgia a specific kind of homesickness, whose sense of pain is similar to that caused by the feeling of envy rather than nostalgia. A feeling of lack, self-translated as loss, whose direct reference is other human beings we value, and their experiences shared online. Morestalgic human beings are those who have the desire to live an experience they have previously understood to be a plausible one, but instead of recalling it from their own past, they substitute this with an immersive navigation experience offered by the web. The past is not actually experienced in the sensible world by those who feel they have lost it, but is permanently archived and at one’s disposal, to be recalled right now and embraced again, with a single click. Nostalgia springs from the source of emotional memory, the memory of life lived, morestalgia invades instead the field of numerical memory, that of names and numbers. In order to work properly, augmented reality requires us to occlude—thanks to technologically advanced gloves and visors, tactile—visual and auditory sensory skills to which our species owes survival on the planet earth. In the same way, augmented nostalgia, a.k.a. morestalgia, is based on the fact that our minds seem induced to process events offered by the screens of portable devices as life lived, and in doing so, to usurp the body’s ability to perform regular rounds of sensory inspection. Compared to the past, the structural difference lies in the amount of exposure of humans to data and rather than the actual data resolution, the context within which the data have been produced and consumed. Regarding myself, I’m both agent and subject of this process.

Riccardo Benassi, Morestalgia (lecture slide), 2019. Supported by Italian Council (2019), produced by Xing. Courtesy the artist.

And how do you see nostalgia as a political tool? (for instance MAGA)

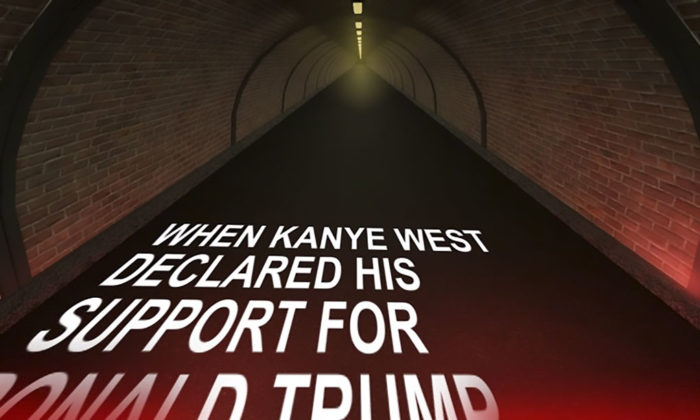

Slippery. One of the reasons I initially came up with the neologism was to make sense of the current political scenario. When, for example, Kanye West declared his support for Donald Trump and wore the MAGA cap, he partially criticized the MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN statement, particularly the word AGAIN because, he said, it focuses attention on the past, instead of focusing it on our common future. And when I noticed several parodies of the MAGA cap circulating online, all focusing on the communication of opposite messages, I started to worry: although the intention was to spread progressive ideas, the basis of communication was always and in any case founded on the word AGAIN, therefore on the idea of restoring something that disappeared, something from the past. This “common” yet “never-lived” past is a post-internet and technologically mediated radicalization of the so called identity politics.

Riccardo Benassi, Morestalgia, 2019, detail. LED digital content. Supported by Italian Council (2019), produced by Xing. Courtesy the artist.

In one of your texts you write: “Walter Benjamin has told me that memory is not an instrument to find back the past but memory is theatre (Living Theatre, I imagine).” Can you expand a bit on this?

That Benjamin’s quote has been a personal guiding light since ages. I understand memory as an integral part of the human creativity. Within Morestalgia, it acknowledges the necessity of diving into the study of History (especially after the post-colonial turn) to the point of being able to feel empathy with all of its individual actors, without exception. A very difficult challenge, I know.

How do you construct your works?

I listen to myself in relation to the surrounding landscape and I try to recognize the emergence of a feeling to which I can give a new form in order to let it survive the transience of the moment.

Riccardo Benassi, Morestalgia, 2019, detail. LED digital content. Supported by Italian Council (2019), produced by Xing. Courtesy the artist.

Your relationship to music is really important. Could you tell us more about it?

Despite teaching Sound Design and having anonymously participated to the creation of several musical celebration within the last subcultures of the ’90 I don’t consider myself a musician. I simply love music and I can’t imagine a life disinfected from the act of dancing, understood here as one of the easiest ways to feel freedom on earth. How fun it has been to compose the Morestalgia soundtrack! From a theoretical point of view I often analyze emerging musical scenarios in order to collect hints about the current society. Within Morestalgia for example one can find a first person analysis of Vaporwave as much as references to Trap music, and more specifically a speculative bridge between Mumble Rap and the so called “word salad” with which several social media contents are titled today.

What is the difference between a “variation on a theme” and proper repetition?

Repetition does not exist, I guess. It’s only a metaphor to make us human beings feel at ease when sensing the atrocity of the passing of time. The famous Heraclitus quote “you cannot step into the same river twice” acquires a new affective value within a digital environment: a digital file can be copied endless number of times but the complexity of feelings while experiencing it always happen once (and it is both individual and collective at the same time).

Nostalgia and FOMO, what do you think is their relationship? And what is the future of nostalgia?

The word Nostalgia emerged within the medical dictionary to define a pathology, and the same can be said today for the Fear Of Missing Out. Recently a term with an opposite meaning has been coined: JOMO (Joy Of Missing Out) happiness of choosing to disconnect from the Internet for a while. I think that FOMO and JOMO are post-internet short-cuts to define pessimism and optimism, therefore are both past-oriented and nostalgic, because they need evidences and proofs (being them Big Data or scraps of fake news). So, to reply to your question, maybe the future of nostalgia is just a form of neorealism in absence of reality.

Riccardo Benassi, Morestalgia, 2019, detail. LED digital content. Supported by Italian Council (2019), produced by Xing. Courtesy the artist.

Humans created the algorithm and now we are teaching the algorithm to behave, see and think like a human. For me there is something odd, when I realize I am contributing in machine learning—while we’re being biologically reprogrammed and the planet is at the verge of collapse. Although it’s difficult not to be nostalgic, what this scenario does to our emotional field according to you? And what does it mean to imagine “a better world”?

Rather than focusing on machines that learn to behave like humans, it still make more sense I guess to pay attention to human beings who behave like machines. And in reference to AI, we sort of take for granted that the only autonomy that AI have is the one of finding the best solution to a human problem for which it has been instructed by a human. So AI is a metaphor to talk about (at least) two human beings, the one who created it and the one who is using it. The point is that this creates a specific hierarchy between the two persons in question. My understanding is that, within the current visibility economy based on prosumers/freelances in perpetual self-design, the person who design the AI is actually the employer of the one using it. Needless to say the employee is working for free, or at least in exchange for a specific digital service. This being said, I think AI, as much as automation, can be helpful in imagining a better world for as many people as possible, it depends on who design it and for which reason. If is true that “the medium is the message” then is also true that AI is not a medium yet, we are still on time. Feeling on time is a good remedy against nostalgia, isn’t it? To reply to your last question: maybe imagining a better world means to cultivate the ambition resulting from the tension between collective growth and the defense of any existing bio-minority.