Necessary Anachronisms

Rethinking Spaces for the Present

What follows is a reworking of an excerpt from my Master’s thesis Ethics of Curating – didattiche del contemporaneo e del decoloniale. A year ago, I graduated while trying to respond to questions that still follow me: why does the experience and sharing of art today require a radical rethinking? And above all, how and through what kind of institution can this be concretely implemented? How does the relationship between past, present, and future change in contemporary cultural programming? Can we imagine a museum or exhibition space capable of operating on multiple temporal planes simultaneously, creating unprecedented connections between memory and future? The feeling remains the same: imagining definitive answers to these questions, hoping for a transformation of such complex and slow-moving structures as cultural institutions, still feels like a utopia.

Amid contradictions and resistances, this text makes no claim to be exhaustive or conclusive. Nevertheless, I believe that as many contributions and voices as possible are needed in order to imagine and strengthen alternatives for a present and future art world that, as it stands, appears marked by deepened inequalities, collective fragility, and increasing social and political control.

These thoughts arise from within a closed and imperfect West and subsequently extend outward to identify in curating a set of exercises oriented toward listening—capable of promoting gestures of openness in order to steer cultural institutions toward an embrace of the present. I therefore decided to approach the issue starting from two themes that could outline a kind of curatorial strategy/methodology: contemporaneity and decolonization. What do they mean? What are they linked to? In what way can these concepts lead to a rethinking of how and where art is exhibited today?

In writing this text, I was guided by the thoughts of authors who inspired me and helped clarify my path: Claire Bishop, Vasif Kortun, Jean-Loup Amselle, and Giulia Grechi, among others. To them, and to those who will read, goes my gratitude.

What is contemporary? What form of contemporaneity does an exhibition space reflect? What does it exhibit, and to what, in turn, does it expose itself? It is important to clarify that this concept, as of now, should no longer be understood as a matter of periodization. Today, it is mostly a method and a practice potentially applicable to any historical period, alluding to an idea of dissonance, rather than to what might be defined as “new.” However, when observing the global landscape of contemporary exhibition spaces, “one realizes that what unites them is not so much an interest in collections, history, location, or institutional goals, but rather the idea that contemporaneity must manifest at the level of image: something new, cool, photogenic, well-designed, profitable.” [1]

Too often, late-capitalist exhibition models and museal practices are concerned with the present—and more specifically, with “being present in the present.” [2] This mere presence, however, implies the suppression of exhaustive self-analysis in favor of a static, crystallized condition in which the institution under examination does not allow itself to change through the very actions it commits to undertaking. In any case, theorizing the contemporary has become an area of academic interest that has recently seen significant growth. In various cases, once again, contemporary refers not so much to style or period but to a chronological sequence that exhausts itself in the present moment. Until the late 1990s, the term seemed synonymous with “postwar” and referred to art after 1945; after 2000, it came to signify art roughly from the 1960s onward; today, that decade and the next are mostly perceived as late-modernist, and 1989 is considered the beginning of a new era, coinciding with the fall of communism and the gradual globalization of markets.

Each of these periodizations has its pros and cons, but the main issue remains the fact that they are all based solely and exclusively on a purely Western perspective. In China, for example, contemporary art begins in the 1970s, when the Cultural Revolution officially ends and the Democratic Movement emerges; in India, from the 1990s onward; in Latin America, there is a tendency to reject a division between modern and contemporary altogether, still questioning whether modernity ever actually materialized. In Africa, contemporary art is traced to the end of colonialism (between the 1950s and 1960s in anglophone and francophone countries; the 1970s in former Portuguese colonies) or even to the 1990s, a period that coincides with the end of apartheid in South Africa and the proliferation of the first African biennials.

It follows that periodizing the contemporary is problematic, as it fails to account for the enormous variety present on a global scale. If, instead, the main directives were inverted and one managed to navigate multiple temporalities within a more political framework, we would approach what Claire Bishop calls “dialectical contemporaneity” [3]—a concept worth proposing both as an exhibition practice and as a method for studying art history. Motivated by the desire to understand the present condition and figure out how to change and improve it, this thinking aligns with the idea that museums and contemporary exhibition spaces can rethink their collections, transforming them into fertile testing grounds for a multitemporal, non-presentist contemporaneity.

In fact, what determines the contemporaneity of a space is its alignment with the spirit of the times—and in this sense, anachronism is what seals this perspective: the contemporaneity of the historical gesture materializes, for example, by juxtaposing and reconnecting works from the near or distant past with modern artifacts. This is one way to counterbalance the frozen quality of collections, which should no longer be understood as treasure warehouses but as archives of the commons—resources that must be carefully managed and brought to life. In this regard, we must defend the idea that institutions should not represent an archive of the contemporary, but rather that they should be creating it.

It is not the present, the current, or contemporaneity itself that defines or makes something contemporary, but rather the exhibition layout, the program, and the stories being told. Dialectical contemporaneity also mobilizes an understanding of the present and future by rereading and reinterpreting the past. Art holds multiple publics whom it is responsible to and it must care for: a public of the present moment, another of the future, and above all, a public that continues to arrive from an unresolved past that will not disappear—and that, for this very reason, must be continuously addressed and carried forward. This public, too, can and must be part of the contemporary, because “it is our gaze toward it that makes it so.” [4] In this sense, the foundation of museums that turn the present into a denied past should be uprooted.

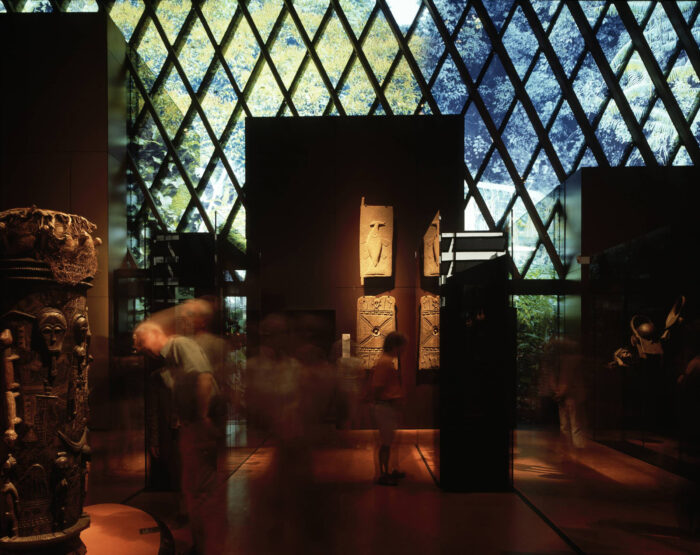

To better understand this, it is worth citing an example offered by Jean-Loup Amselle in his book Il museo in scena: the permanent collection of the Musée du quai Branly (Mqb), largely inherited from the Musée de l’Homme and dedicated to so-called primitive artifacts, situates the museum in a kind of present turned past—“in a floating temporality that anthropologists call the ‘ethnographic present,’ a phenomenon exacerbated by the juxtaposition of prehistoric objects with exotic artifacts whose lack of biography leaves their time period unclear.” [5] In this case, as in many others, a broad operation of denying the contemporaneity of certain cultures is carried out.

It is time to understand that a museum should not act as a conservative institution incapable of focusing on the past it wants to narrate, on its present—including the social changes that cut across it—and on its future. Contemporary art institutions are starting points for social change and collective expressions that discuss and reflect shared values. Therefore, each of them should be subject to what we might call an “obligation to contemporaneity.” [6]

Every museum should be able to respond to the questions of today and no longer be content with merely storing and displaying objects. This should be true not only for classical museums like the Louvre or the Musée de l’Homme but also—indeed especially—for museums of contemporary art.

The Louvre, in particular, represents the paradigmatic example of a museum housing the classical heritage mainly focused on Western art history from Egypt to Greece, to the classical art of the 18th and 19th centuries, as its ‘ethnographic’ collections were transferred to the Musée du Trocadéro. Today, this giant institution has become contemporary in two ways: first, through the addition of the glass pyramid designed by architect Ieoh Ming Peï, and then with the 2000 opening of the Pavillon des Sessions dedicated to the display of ‘other cultures’ and ‘other arts’—from an entirely aestheticizing perspective.

Thus, in the case of the Louvre, “the contemporary becomes an aestheticized exotic, aligned with an attempt to universalize cultures alongside other ‘masterpieces‘ like the Mona Lisa, the Venus de Milo, or the Winged Victory of Samothrace.” [7]

In reality, however, this has not led to any genuine “being contemporary” of museal practices within this massive institution, which would severely need to question itself. If everything is museified, preserved, and stripped of historicity, what is the function of this space at a time when entire cities are becoming museums themselves, devoted solely to attracting mass tourism? The capacities of this type of institution—and above all, its potential—are often transformed into assets to be leveraged and brands to be marketed to sustain the present moment. It could be argued that they have given up on their future. Or worse—that they are not even aware of it.

To decolonize an exhibition space literally means to change both the practices of display and the ways we think about what is representable, engaging with the foundations, roots, and heirs of everything that finds a home within it. To decolonize implies resisting the perpetuation of categories imposed by colonialism and defending radical multiplicity. To decolonize is to understand that every culture is embedded in the flow of history, and that, in this sense, we must learn to consider multiculturality not as an exception but as a necessary condition—one that gives rise to an extraordinary capacity to translate diverse knowledges and identities as a model for cultural development and interpretation of reality.

In fact, today we are dealing with a global geopolitics and marketplace of identities and memories, in which museums, galleries, and foundations represent the contemporary to the extent that political issues have widely become issues of identity, memory, and recognition. This demands not just superficial inclusion, but a deep challenge to the very foundations on which the idea of modernity has been built.

Decolonizing also means understanding art today as a practice of remediation and transgression of curatorial language in an expanded sense. In this regard, a key point to focus on is how present-day artistic practices can evolve without being bound to the fixed goal of an exhibition or a collection’s reinstallation—and consequently, how an expanded exhibition model, with different objectives, can contribute to presenting and discussing the present. In some cases, this is not merely a formal exercise, but a need and a necessity.

A challenge to the mechanisms of the status quo through new representational apparatuses could therefore be the solution for evolving in this regard. However, this evolution should also entail a moral advancement, supposing that one of the missions of today’s cultural spaces should be “to provide ethical and moral perspectives on our collective cultural and artistic memories.” [8] This raises a fundamental question: if we are to imagine a different mode of relating to the world, what kind of institution can we imagine? What new models of exhibition and representation might emerge?

To begin answering this, it is essential to investigate the frameworks of these places—deconstructing what has layered them over time—and to begin a commitment on the part of exhibition spaces to position themselves not as places separate from the world or from society, but as agents of cultural and political restructuring.

It is important to remember that these are machines of cultural heritage, which pose and produce questions about unresolved, ignored, or erased histories of the past, and which—at their best—should negotiate, cultivate, and test possible futures. The mandate of cultural institutions was clear from the start: to do all in their power to claim a world better than the one they inherited—not to worsen things, but to move toward an ecologically sustainable world, toward the right to freely access knowledge, common resources, and essential services such as health, education, and equality among living beings, including those without a voice.

In this sense, these institutions move with the rhythm of society and mirror it, functioning as devices that reflect. In fact, it is essential to try to avoid the powerful forms of exclusion—which are, unfortunately, still too common—arising from the fact that not everyone is offered the same opportunity to see themselves reflected in what is displayed. In this regard, we should reinforce the idea that any exhibition space is an educational and research space that should keep its doors open to everyone, given its increasingly urgent connection to the environment surrounding it. In this sense, any initiative, venue, or project devoted to transmitting art to people belongs to society, or at least is obligated to become part of it.

Precisely for this reason, it would be helpful to propose a different perspective for visitors—no longer seeing them merely as passive spectators of final exhibitions, but actively involving them in the redefinition of cultural policies and in the management of the heritage that is exhibited and/or preserved. Through these experiments in exhibition and museum devices and practices, it is possible to identify new criteria and approaches to ensure a space that is representative and accessible—essential in its public role within society.

“In this sense, the museum itself should stage its anthropophagic impulse, offering itself as an edible body, exposing itself reflexively to its own vulnerability and ambiguities, inviting visitors to imagine a more carnal way of penetrating it, of literally incorporating it, encouraging a sensory experience that extends beyond sight alone.” [9] Every exhibition space needs to remain in dialogue with the context in which it is situated, enacting a provocative rethinking of contemporary art in terms of a specific relationship with history, propelled by pressing social and political urgencies. Colonial history, related postcolonial issues, gender concerns, and all the challenges of the present are what make a space truly contemporary. The result of all this should then suggest new multitemporal mappings of history and artistic production—especially detached from national frameworks—in order to help highlight what was previously marginalized, removed, or denied. Only through a genuine practice of decolonization that originates in the roots of the social, political, and cultural context we can hope for a new representation of contemporary exhibition spaces.

Radically rethinking these places could mean starting to recognize them as spaces crossed by shifting meanings, in constant dialogue with the context that generated them. But today, in such a complex moment, what can we realistically expect from these spaces? Will this need for change ever be fully understood—and partly applied? Can we still actively contribute to testing them, to stimulating their transformation, or are we facing a dead end? While cultural institutions have often been at the root of systemic inequalities, they can also be stages for internal transformation, driven by a genuine urgency to evolve and improve. It is from this belief that this text originates, and it becomes part of a broader critical act of holding accountable something we love—something we want not only to survive, but to flourish as the best version of shared artistic and cultural experience. Perhaps the goal will be reached only when museums, galleries, foundations, and independent spaces are truly able to take responsibility for the stories they tell—of art, of the world, of collective memories—becoming, at last, places of knowledge based not on power, but on listening, plurality, and care.

[1] Bishop C., Museologia Radicale, Johan & Levi, Cremona, 2017, p. 19.

[2] Scotini M. (curated by), Utopian Display. Geopolitiche Curatoriali, Quodlibet, Milan, 2019, p. 56.

[3] Bishop C., op. cit., p. 28.

[4] Amselle J.L., Il museo in scena. L’alterità culturale e la sua rappresentazione negli spazi espositivi, Meltemi, Milan, 2017, p. 41.

[5] Ivi, pp. 28-29.

[6] Ivi, p. 31.

[7] Ivi, p. 32.

[8] Allain Bonilla M., Alcuni aspetti teorici ed empirici sulla decolonizzazione delle collezioni occidentali, published in Hotpotatoes, October 6, 2018.

[9] Grechi G., Decolonizzare il museo. Mostrazioni, pratiche artistiche, sguardi incarnati, Mimesis Edizioni, Sesto San Giovanni, 2021, p. 122.

Bibliography

Allain Bonilla M., Alcuni aspetti teorici ed empirici sulla decolonizzazione delle collezioni occidentali, published in Hotpotatoes, October 6, 2018

Amselle J.L., Il museo in scena. L’alterità culturale e la sua rappresentazione negli spazi espositivi, Meltemi, Milan, 2017

Bishop C., Museologia Radicale, Johan & Levi, Cremona, 2017

Grechi G., Decolonizzare il museo. Mostrazioni, pratiche artistiche, sguardi incarnati, Mimesis Edizioni, Sesto San Giovanni, 2021