Mirror Mirror

An essay on looking through the glass in search of images

Visual art summons what is other than real and delivers it to us as if it were a presence. It spirals into a void of anesthetic forms, gestures emptied of vibration, echoes of meaning collapsing into silence. Art now exists through its own withdrawal: through its inability to communicate anything but desperation, wordlessly, through aesthetic shells that stand immobile, frozen mid-breath. And I ask myself: what can I still comprehend, interpret, imagine when I look at art today? Perhaps there is something left, a residue of what we call “human.” Something whispering, almost inaudible, testifying that we are still here: you, me, all of us, bodies present in the here and now, with a will, with a force, to bend and mold reality against the tides of aggression, against the undertow of depression. Perhaps this is where art lives now—not in its exhausted forms, but in the possibility of resistance that trembles just beneath them, dissecting the ultimate collective psychosis: the narcissism of the will. Breaking away from the moralistic notion that self-obsession will be our downfall, writer Matt Colquhooun offers a vision of narcissism rooted in transformation, rebirth, and the transcendence of the ego.

Likewise, in this essay, I propose an exploration of a contemporary, speculative artistic movement that gravitates around the mirror as a medium, tracing its lineage through art history while examining its manifestations in today’s practices. Drawing on a selection of works encountered during my research, I aim to illuminate the subtle correspondences that connect mirror-based art forms across time. Could these practices be shaped by the social media logic of so-called “Instagrammability,” where visibility becomes a claustrophobic compulsion to appear—on surfaces, in mirrors, and on black mirrors alike? In this framework, stillness disrupts the imperatives of speed, efficiency, and utility. Perhaps, then, these works operate as a contextualization of our positionality in the world, reflecting not only images but also the conditions of our gaze caused by all poor images of violence instilled through online and offline circuits.

In early 19th-century European painting, mirrors were primarily narrative props embedded within tightly coded social and moral frameworks. Rooted in Neoclassical portraiture and Romantic domestic scenes, mirrors often symbolised virtue, vanity, or temptation, signifying presence and authorship, affirming identity and the author’s positionality. In Dutch painting, it was customary for mirrors to serve a duplicating function: they repeated what was present within another space also as a form of mastery. With Velázquez’s Las Meninas, the mirror reflecting King Philip IV and Queen Mariana invited and still invites contemplation on the nature of art, reality, and the viewer’s role within the scene. “The real function of this reflection is, in fact, to draw into the painting that which is legitimately external to it: the gaze that has composed it and the gaze toward which it is offered.”

By the late 20th century, mirrors ceased to function primarily as depicted objects. Instead, they became integral materials, transforming from motifs into mediums. Artists began to work with mirrors directly, implicating viewers within the artwork and collapsing distinctions between representation and participation. Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Mirror Paintings (begun in the 1960s, widely revived in the 2000s) are pivotal here. By replacing traditional painted backgrounds with polished reflective surfaces, Pistoletto renders the spectator part of the composition. The “image” exists only when the viewer engages; authorship becomes distributed. The mirror thus ceases to represent—but produces experience. Similarly, Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms dissolve individuality entirely, surrounding audiences with infinite recursive reflections. Here, mirrors generate immersive environments, destabilising the boundary between self and collective, real and virtual. These practices resonate with Michel Foucault’s writings on visibility and power. In Discipline and Punish (1975), Foucault describes modern society as structured by mechanisms of observation and self-surveillance—mirrors literalise this dynamic, producing a constant awareness of the self as image. In an age dominated by screens, mirrors operate like technological interfaces: unstable, participatory, and generative. Think of Joan Jonas’s Mirror Piece I & II return in recent days as both a revival and a reminder—an early feminist and conceptual work made newly urgent. Staged on the terrace of the Neue Nationalgalerie, the performance used mirrors and plexiglas plates carried by a corps of performers in choreographed movements. These shifting reflective surfaces fragment space, the performers, and the audience, making viewers not only observers but also part of the work—caught in reflections, disrupted identities, and shifting perceptions. Jonas herself has described the mirror as a device to alter the image and to include the audience as reflection, making them uneasy as they view themselves in public. The performance thus becomes a site of tension: between visibility and exposure, between looking and being looked at. In this 2025 iteration, the work also invites reflection on temporality: how a piece first performed in 1969 remains alive—how its questions around gender, identity, perception resonate in the present.

This evolution of mirror surfaces invites us to reconsider the ontology of the mirror within visual culture. Historically, the canvas has been the dominant surface of representation: it absorbs pigment, fixes images, and projects the artist’s vision outward. The mirror, by contrast, resists fixity. It produces images only in relation to its environment and the viewer, always shifting, always contingent. Walter Benjamin’s reflections on mechanical reproduction are instructive here. In his 1936 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, Benjamin argues that photography and film erode the “aura” of the unique artwork by multiplying images endlessly. Mirrors anticipate this logic: they generate infinite reproductions of reality in real time, decentralising authorship and destabilising originality. Unlike the canvas, the mirror refuses to “contain” representation. Instead, it enacts it. In doing so, mirrors align more closely with contemporary art’s turn toward participation, performativity, and immersion. They are no longer supplementary objects within the frame but primary agents shaping the conditions of vision. Gerhard Richter’s practice anticipates the role of digital screens as contemporary mirrors: surfaces that both reflect and construct identity in real time. Just as Richter’s Mirror Paintings implicate the viewer in the image, our devices continuously return mediated versions of ourselves, collapsing distinctions between subject and object, observer and observed. In this sense, Richter’s Mirror Paintings act as a conceptual bridge, heralding an era in which mirrors—and, by extension, screens—operate not as passive tools of depiction but as generative, dynamic canvases where reality, image, and self coalesce.

In the new millennium, mirroring is no longer merely reflective and situating, it has become a widespread strategy, a subtle way of eluding the hyper-visibility imposed by the attention economy. More and more artists are choosing to imply Perseus’ stratagem: to imply mirrors to mediate reality—Medusa—and survive maintaining a safe distance that allows one to process the world and its most difficult aspects. At times when violent imagery, whether in news or popular culture, often demands a kind of passive absorption we’re asked to watch, consume, and internalize. Mirrors and reflective surfaces deflect and return the gaze. Instead of allowing a one-way consumption, they implicate the viewer—asking who is looking and what position am I in relative to this image?

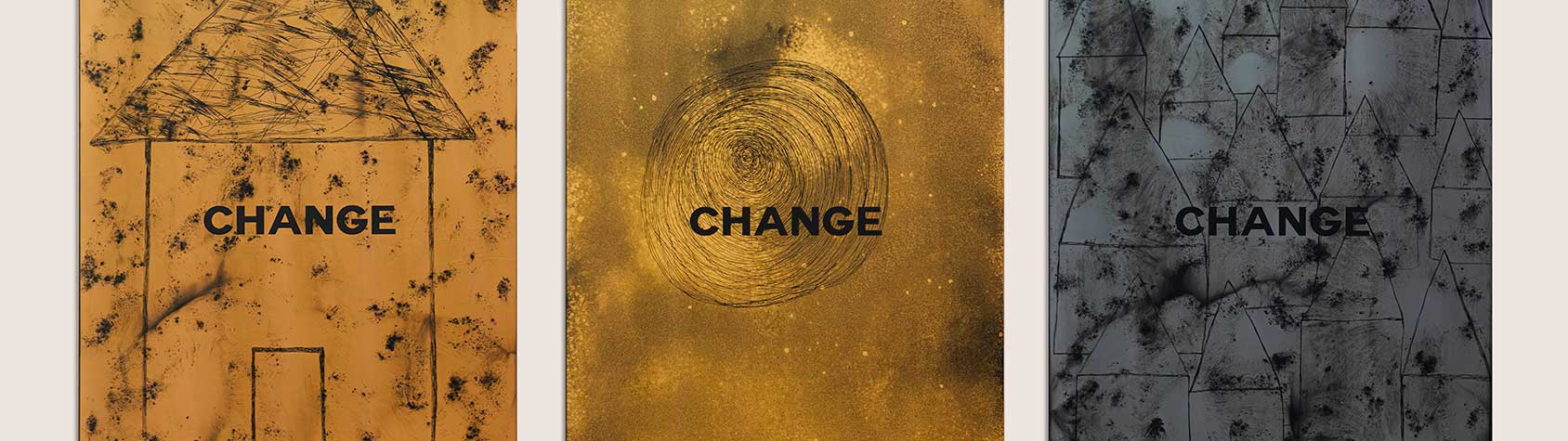

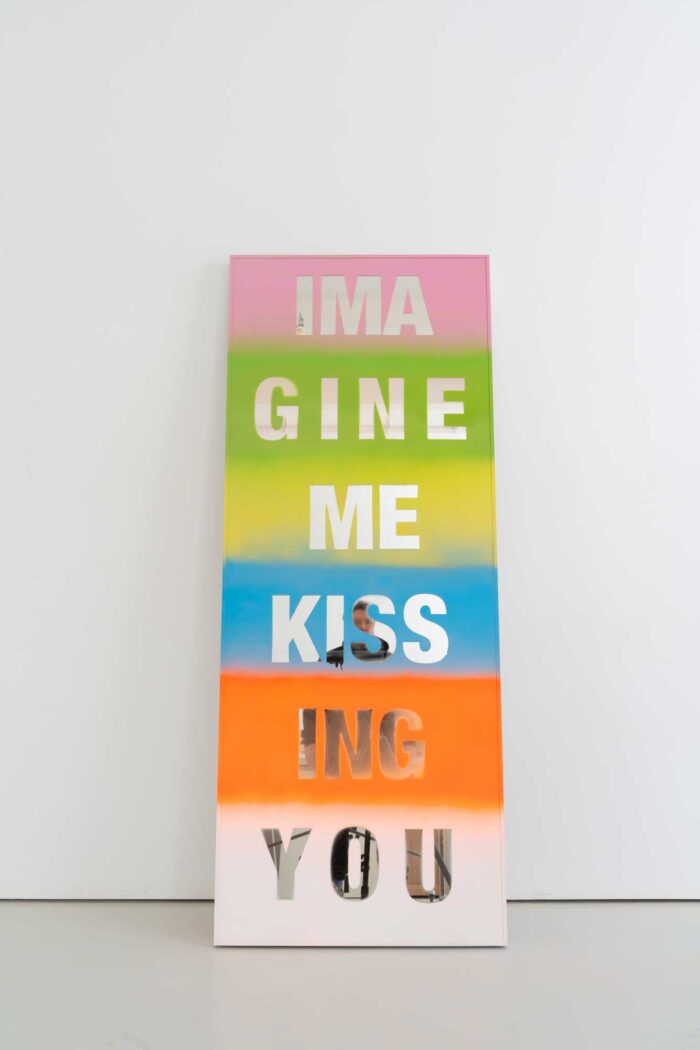

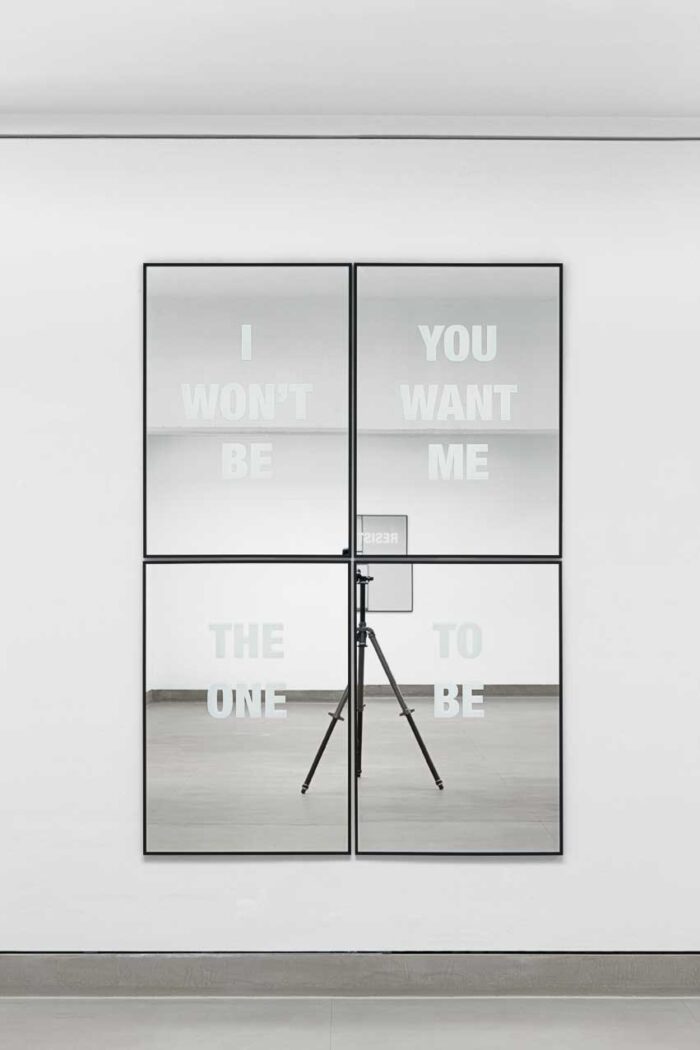

A compelling example is artist Olga Migliaressi-Phoca’s mirror works: she transforms mirror glass into expressive art through bleaching, acid-induced patinas, scratching, engraving, and epoxy paint application. Each piece is uniquely crafted with hand-applied processes that can span weeks or more. Using the mirror as both canvas and subject, she “vandalizes” reflective surfaces—collapsing viewer and art into one. Through altered logos, fragmented narratives, and reflective distortion, they invite viewers to reconsider how meaning circulates and evolves within the reflective surfaces of our mediated world. As the artist mentions, the medium of the mirror creates the possibility of the creation of a floating space which changes based on the environment it is situated in. Similarly, the mirror surface (with its reflections) combined with text overlays or screen print produces a layering in Eike König’s work: what is the mirror showing and what is being said create a tension that can make visible what is otherwise masked or normalized. Yet we continue to be present in the imposing virtual surface.

In Nick Mauss’ work, the mirror functions less as a tool of self-reflection and more as an unstable surface that resists the clarity we might expect from it. Rather than affirming identity through a seamless image, his mirrors fracture space and vision, redirecting the gaze into a play of obstructions, eros, and uncertainty. By “internally vandalizing” the mirror, in his own words, Mauss corrupts its promise of transparency and reliability, producing instead an entangled image that destabilizes both subject and viewer. This refusal of the mirror’s traditional role—whether as a metaphor for narcissism or a technology of representation—creates an erotics of misdirection, where the gaze is never fully satisfied but continually deferred, caught in the instability of reflection.

“I’d heard that Duchamp’s Large Glass was at once point intended to be mirrored. I was interested in Dan Graham’s ideas around the fracturing of space, of inside and outside, the melding of surveillance and decoration in the rococo Amalienburg Pavilion in Munich, and his idea that ‘the mirror allows people to perceive themselves perceiving.’ Eventually I synthesized techniques adapted from the decorative arts, modernist cinema and performance, folk traditions of glass painting, and early photographic methods to arrive at a process of making paintings in reverse on the underside of sheets of glass, and mirroring them, so that line, color, the viewer herself, and the architecture of the exhibition site are collapsed.” (Nick Mauss, personal communication, 17 September 2025)

Another emblematic example is the work by Giovanna Repetto. In her words, she works with reflective surfaces to evolve the concept of identity and point of view. Specifically, in her series Untitled (closed in) she began eliminating surfaces that split reality in order to focus on the real present. As she asserts, “I use the mirror as a neutral instrument—one that does not discriminate or filter. It becomes a receptive surface, recording the visual streams of scenarios and actions unfolding before it, capturing them as atmospheric images in perpetual metamorphosis. Through a pictorial intervention with a black marker, I ‘close’ the mirror, transforming it into an archive of images that resist manipulation.” An ultimate expression of invisibility and silence yet asserting an act of counter-representation to feel that black mirror we’re constantly facing.

Perhaps what is at stake in these practices is not merely the proliferation of reflective surfaces, but the question of how we search for images in an age already saturated with them. To look into a mirror-work today is to confront not just one’s own reflection, but the algorithmic logics, cultural desires, and social compulsions that condition visibility itself. Visual art summons what lies beyond the real and delivers it to us as presence, yet mirrors remind us that this presence is never stable: it shimmers, slips, and reconfigures with every gaze. Through mirrors, we glimpse a different ontology of the image—not fixed, but relational, resistant, trembling. If the canvas once served as the sovereign surface of representation, the mirror instead offers us a practice of searching, one that acknowledges contingency, multiplicity, and instability as constitutive of our experience. In this sense, mirrors are tools in search of images of images of positionality of ourselves in the now, today, within proliferating opaque images that we touch through screens but never really grasp and feel related to.