Millesuoni

Sonic Strategies of Territory and Escape

In Millesuoni, Deleuze Guattari e la musica elettronica (2008), Emanuele Quinz distills some of the key ideas on the nature of sound formulated by Deleuze and Guattari over the course of their work. Central among them is the dynamic of territorialization and deterritorialization—a strategy of appropriation and subsequent release, activated in the alternation between refrain and music.

A child humming alone to ward off the fear of the dark is engaging in a process of territorialization, marking a boundary within which they situate themselves as a subject. If territorialization belongs to the refrain, music—of which the refrain is an integral component—sets in motion the opposite movement: deterritorializing the forces that define the refrain. Music tends toward abstraction and dissolution, eluding territoriality altogether.

As Deleuze and Guattari write: “A child reassures himself in the dark, or claps his hands, or invents a way of walking […] or else chants ‘Fort-Da’ […]. Tra la la. A woman hums… A bird launches its refrain” (A Thousand Plateaus, 415)—revealing a continuous alternation between subjectivation and transformation, between flow and becoming.In the works of Nicola Di Croce, Nicolò Pellarin, and Ramona Ponzini presented in Millesuoni (curated by Lisa Andreani, Neun Kelche, Berlin, 1–13 July 2025), this interplay of the two movements is clearly perceptible. It manifests as a constant shifting of perception—from listening to touch, from listening to vision—and as a continual repositioning of the body within space

Cecilia Bima: Your work Attuning to / Resonating with, presented at Neun Kelche, is a multichannel installation that reproduces recordings made in a workshop setting at the Teatrino of Palazzo Grassi in Venice. The displacement—and consequent deterritorialization—of a work so strongly defined by its site of origin is a crucial aspect of its conception. How did you address the challenges posed by this shift?

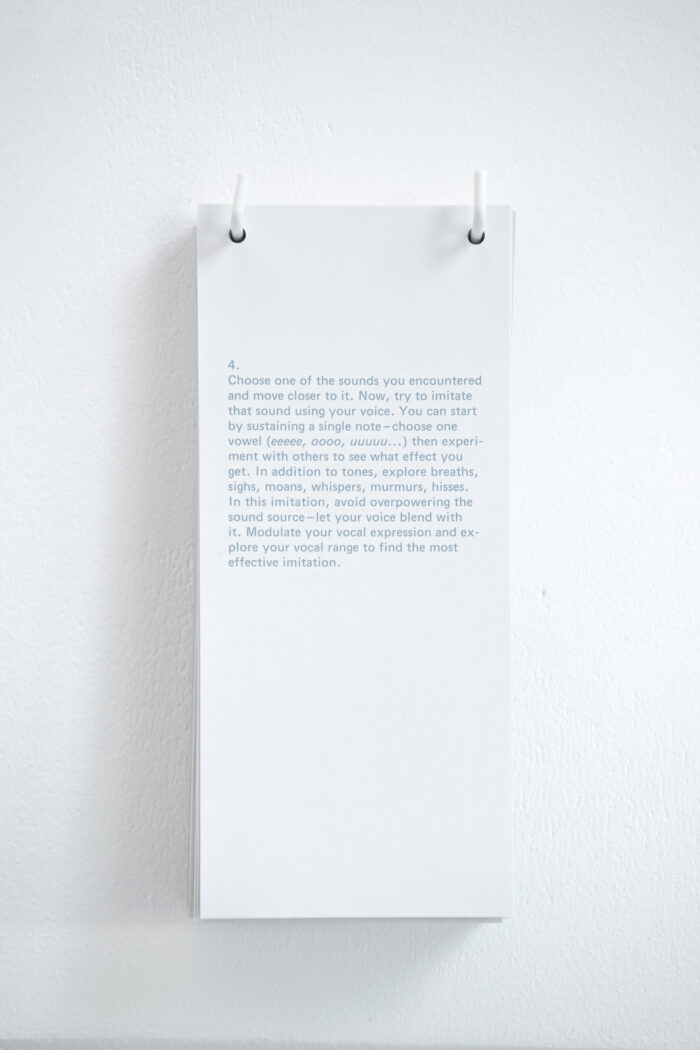

Nicola Di Croce: Attuning to / Resonating with began as a workshop at the Teatrino di Palazzo Grassi (Venice, 2024). Its aim was to engage with sounds usually dismissed as “disturbing” and hidden at the margins of buildings: ventilation systems, refrigeration units, servers. With participants, we first listened closely to their textures and rhythms, then imitated them with our voices, forming a choir that explored modes of attunement and resonance with these mechanical presences. Rather than relocating the project, I chose to re-actualize the conditions that allowed this dialogue between humans and machines, starting from the recordings and outcomes of the workshop. My interest lies in the unnoticed presence of such sounds. A refrigerator, for example, hums constantly in most homes yet passing unheard. This inattention thus raises the question: what role do such sounds play in our daily life?

In Berlin, the shift of context is deliberately paradoxical as it recreates a situation that could exist anywhere. The “music” born from such vocal interaction resonates with Quinz’s reading of Millepiani: music emerges from a détour, a deviation of the refrain, uprooting it from its territoriality. In fact, if the Refrain territorializes—creating order, anchoring the body to earth—this project seeks not deterritorialization but reterritorialization. It explores how to experiment with deeper connections between bodies and territory. Such processes may start in marginal areas where “disturbing” sources persist—wind turbines, nuclear plants, military zones—placed strategically where their noise is least heard. But they can also unfold inside museums, theaters, and galleries, saturated with background mechanical sounds. By shifting attention toward them, recognizing their musical potential, and integrating them into a choir of voices, the project aims to enact reterritorializing deviations.

Cecilia Bima: In Attuning to / Resonating with, the practice of attunement revolves around the sonic presence of the non-human: participants’ voices come into resonance with machines, infrastructure, and household appliances. This recalls music’s deterritorializing potential and the related flow of becoming that Deleuze and Guattari describe—a tension I see embedded in the score of your work. Listening, followed by vocal attunement to non-human sounds, initiates a gradual transformation from human to machine. How did the piece take shape in relation to this tension?

Nicola Di Croce: The practice of attunement in this project does not aim at turning humans into machines, but at opening a dialogue with an agent that produces sound yet cannot listen. What interests me is disappearance and camouflage: the blending of voices with a mechanical source usually considered disturbing. Through vocal practice, participants explored how to merge with such sounds without vanishing, remaining present without standing apart. The initial score was simple: imitate the machine. Beginning with the hum of a refrigerator, voices sought resonance, finding success in moments of blending. This act recalls the natural process of learning through imitation—an infant repeating sounds until they take shape as words. In this case, however, the roles are inverted. Instead of being corrected, we adapt ourselves to the machine. We imitate it, then integrate it into a choir, giving it a role as if it were another voice. The mechanical source sets the tone and timbre, like a solo instrument unaware of its role. The choir responds first by letting the source emerge, then integrating it with the other voices, and finally overwhelming it until it fades. This creates a dynamic of shifting roles: the machine is alternately soloist, choir member, and a vanishing presence once its qualities are learned and used as a new language. The aim is not to erase difference but to resonate with the machine while maintaining the choir’s “humanity”. The experiment moves beyond meaning toward affective and expressive levels of understanding the machine, positioning the voice as material, embodied sound capable of forming relations even with what does not listen back.

Cecilia Bima: Negotiation is another key element—present both during the recording process and in your spatial interventions at Neun Kelche. In the first case, diverse vocalities were required to respond to non-human sources, to the spaces in which these were diffused, and to one another. In the second, I see this same negotiating impulse in your decision to install work even in unconventional sites, such as the bathroom. What role does this notion of negotiation play in your artistic practice?

Nicola Di Croce: A central aspect of the score lies in the interaction among participants. No precise instructions are given on how to interact with the sound source: the group must find its own modes of coordination, often through non-verbal agreements. What interests me most is not only the sonic result but the metaphorical and political dimension of this practice. An accord is both an overlapping of notes to form a chord and a negotiation between parties. Negotiating does not mean blind acceptance, but a process of exchange, sometimes playful, sometimes delicate. Seeking negotiation with the non-human means first recognizing its role in shaping our environments—from the hum of domestic appliances to the resonance of industrial infrastructures—and then reflecting on the power relations they sustain, often unequal and exclusionary. The accord produced by the choir becomes a metaphorical tool for collective governance, pointing to participatory ways of sharing resources and spaces. In the exhibition, I sought to extend this logic of negotiation by breaking the conventional schema of encountering artworks. The installation offered three listening points, each presenting a dialogue between two speakers: one with the mechanical sound, the other with the choir’s response. For the third station, I used the gallery bathroom, where the existing fan replaced the recorded machine sound. A speaker played the choir’s interaction with it, creating a direct relation between the site and the recorded process. This choice aimed to materialize the creative process, adapting it to the exhibition space while revealing its mechanisms. More broadly, I see such choices as opportunities to bring audiences closer to the transformative potential of art—its ability to reveal the political and social significance of listening, especially when it concerns the unnoticed sounds of the everyday.

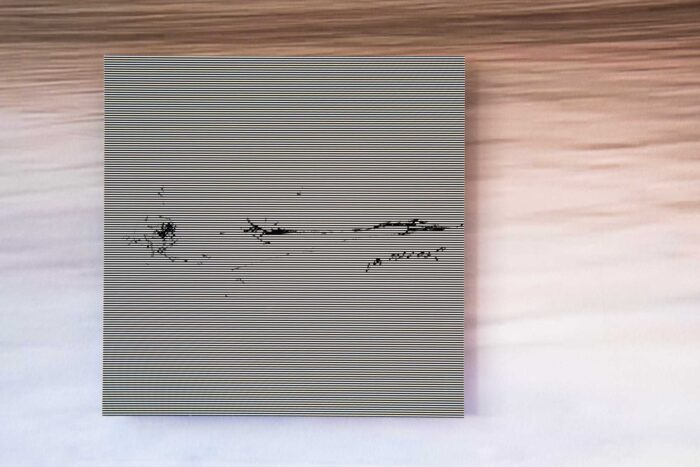

Cecilia Bima: Bones, skyscrapers is a composite image of three elements, appearing like a mirage—an imagined landscape generated through an exploration of the relationship between human presence and surrounding environment. Here, the imaginary operates through vision, initiating a process of spatialization—or, in Deleuze and Guattari’s terms, territorialization—tracing limits and rendering them perceptible. How do you relate to space during the conception and then the production of a work?

Nicolò Pellarin: Ahh relationships, to me to relate with the landscape can be also going grocery shopping; it does not necessarily imply a research-driven approach. To relate to space means being aware of where one is and being able to shape one’s practice accordingly. Simply using your eyes properly. I would therefore ask the reader: what does relation mean to you? The core of my practice is rooted in a daily, intimate, and sustained engagement with the landscape, which I understand both as view and vision: a reciprocal passage where what I encounter and what encounters me continuously reconfigure one another. In this sense, the conception of a work emerges within what I call a form of visual life, where images, rhythms, and signs are not simply observed but inscribed through movement and perception.

This dynamic relation positions Graphic Design—or perhaps more precisely, Writing and Translating—not merely as a medium of communication but as a mode of interpretation and spatial negotiation. My practice resonates with the theoretical paradigm of Landscape as Text elaborated by scholars such as Serenella Iovino and Thom Van Dooren, where the landscape is conceived not as a static backdrop but as a discursive, affective, and narrative entity. To conceive a work thus means to engage in a process akin to writing: a continual act of tracing, translating, and reterritorializing space through visual form.

In production, this becomes an affective strategy—an alternative to the mainstream paradigm of “translation”—seeking instead proximity to the material and “real” world. What emerges is less a representation of space than an attempt to dwell within it, producing signs that remain attuned to the lived conditions of the environment.

Cecilia Bima: Bones, skyscrapers is the only purely visual work in the exhibition. Yet it inhabits a space defined and activated by sound. What meanings and connections emerge from its coexistence with the predominantly sonic works of Di Croce and Ponzini?

Nicolò Pellarin: In this case, how can we approach a “dialogue” with a context and methodology that are entirely different from our own? My work does not function as a mere backdrop, but as a correlation of approach. The interplay emphasizes the interconnectedness of sensory experience: the visual shapes attention and interpretation, while the auditory modulates emotional and bodily response. Meaning emerges not from a single modality but from their coexistence, highlighting the capacity of different forms of perception to converge, contrast, and enrich one another within a shared spatial and experiential framework.Finally, I would say that what I have done is simply add a word to a text already full of meaning.

Cecilia Bima: In a 1978 lecture at IRCAM in Paris, Deleuze remarked: “It is not so much the sound that refers to a landscape, as music that develops an internal soundscape.” This strikes me as relevant to your practice as both artist and curator, where music often plays a central role. What role did music play in shaping and projecting the mirage of Bones, skyscrapers?

Nicolò Pellarin: Music in itself may not be the right term—the key point in my work is the reference to sounds that can translate the atmospheres of the very life of materials. The crack, the visual repetition, the pixels, the matter itself, the rubbing of fingers as a sign of something that is eroding and therefore living, withering, being born. In this sense, then, it is a semantic translation that lies between sign and sound, which can—or *could*—translate it. However, I would prefer to conclude this interview with a song—for the sheer pleasure of it, and also because I just happened to hear it by pure chance.

The Silent Orchestra–Biosphere (1997)

Cecilia Bima: Your work É-temen-an-ki, presented at Neun Kelche, is striking for its layered perceptual registers. It seems to unfold through three acts of shifting or deterritorialization: first, the use of onomatopoeia as a movement from sound to written verbal language; second, the possibility of experiencing sound through another organ—one not typically entrusted with hearing; and third, the cultural and geographic displacement toward a Japanese context, a process potentially disorienting for a European listener. How do you interpret this shifting dynamic?

Ramona Ponzini: In É-temen-an-ki, the dynamics of displacement unfold first and foremost at the vocal level: the voice—my own and that generated by artificial intelligence—is not treated as a mere semantic vehicle, but as sonic matter, as “grain” that exceeds the plane of meaning and restores its vibratory and pre-linguistic nature. Onomatopoeia, in this perspective, functions as a phonosymbolic device that reactivates a dimension in which sound and phenomenal experience coincide without the mediation of the logocentric code.

The second level of displacement is perceptual: through the tactile masks, sound is relocated within the body as vibration, dissolving the hegemony of the ear as the privileged organ of listening. Here I am interested in what Jean-Luc Nancy calls the “being-with of sound”: its resonant nature, which never belongs to a single body but is distributed and shared. Expanded listening thus becomes at once a political and aesthetic gesture, capable of including perceptual differences and proposing a plural sensory ecology.

Finally, the cultural and geographical shift toward the Japanese onomatopoeic system enacts a further deterritorialization: a departure from the European semantic and phonetic territory, dominated by the primacy of the logos, in order to engage a linguistic tradition in which sound maintains an immediate and iconic relation to the real. This is not an exoticizing move, but rather a critical strategy to imagine alternative genealogies of communication, where the human and synthetic voice might converge into a universal alphabet. In this sense, the three displacements—vocal, perceptual, and cultural—are not separate elements but variations of a single movement: that of returning language to its original dimension as sonic energy, deterritorializing the sign in order to restore it to vibration.

Cecilia Bima: In É-temen-an-ki, you also question the notion of access, understood as the ability of a subject to experience, enter, and use a work, space, or service. By proposing an “expanded listening” in which the hand becomes an organ for hearing, you challenge conventional modes of perception, opening the experience to sensory or cognitive differences. How did you address subjectivities whose perception diverges from the norm in conceiving this work?

Ramona Ponzini: For me, the notion of access is not a functional corollary of the work but an aesthetic category in its own right. The “expanded listening” I propose in É-temen-an-ki arises from the recognition that sound is, above all, vibration and that, as such, it does not belong exclusively to the domain of hearing. The ear, elevated to sovereign organ by the Western tradition, is only one possible mediator; the skin, the bones, the entire body are equally sites of reception.

Through the tactile masks, I sought to restore this primary condition of sound: never localized but diffused, never belonging to a single body but propagating across a shared field. In this sense, auditory disability is not a lack to be compensated for, but a perspective that reveals the shared and transmodal nature of the acoustic phenomenon. Far from being an external “target,” those subjectivities whose perception deviates from the norm become privileged interlocutors, capable of destabilizing the restricted ontology of listening and revealing its plural dimension.

Returning briefly to Nancy, who describes listening as a form of “being-with,” we are reminded that sound is never private property: it is always a crossing, an echo that binds bodies, times, and spaces. From this perspective, accessibility is not a concession but a possibility of redistribution: an invitation to rethink listening as a collective and differential practice, rather than an individual and normalized experience. É-temen-an-ki thus seeks to problematize the very concept of access, transforming it from a threshold of exclusion into a space of epistemological, aesthetic, and political opening.

Cecilia Bima: You often invoke the Tower of Babel when speaking of the incommunicability of a sound sign stripped of meaning. Yet this same limitation can also present itself as pure possibility—as in the material sonic manifestation of an “emptied” language. Like the alternation between music and refrain, how do these two notions—limit and possibility—intersect in your work?

Ramona Ponzini: The myth of Babel, the first document tradition gives us on the diversity of languages, is for me both a narrative of loss and of proliferation. The Babelian dispersion represents the fracture of an original unity, but also the possibility of plural worlds, each inscribed within its own linguistic forms. Here the theory of linguistic relativity developed by Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf becomes a crucial reference: every language is not a mere label attached to a preexisting reality, but a cognitive device that orients perception and categorization of the world. From this perspective, the limit of incommunicability is inverted into the very condition of difference and ontological openness.

In É-temen-an-ki I sought to inhabit this paradox, translating it into sonic terms. The voice does not merely convey meaning, but offers itself as acoustic matter that exceeds language. When the sign is emptied of its referential function, what remains is its vibration: a phonosymbolic and affective force capable of opening a pre-rational perceptual channel. It is in this interval that limit becomes possibility: no longer to say, but to feel; no longer to reduce the world to concept, but to restore it, as a shared and sensible experience.

This tension between limit and possibility also resonates with the dialectic between music and refrain described by Deleuze and Guattari: what restrains and delimits is also what generates a field of resonance and differentiation. In this sense, É-temen-an-ki situates itself within the ambiguous space between language as a grid that orders reality and sound as an excess that destabilizes it. It is not a matter of choosing between the sign and its absence, but of showing how language itself can become an opening onto another dimension, where perceiving precedes—and at times replaces—understanding.