Mediterranean Hauntology

Napoli, dubbing history and music as method, or how to build new southern narratives to face the techno-reactionary colonizer present

This interview was originally streamed via Stegi.Radio and featured in the online event Mediterranean Futures: Napoli curated by Giovanni Napolano.

“Ghosts of my life,” Mark Fisher once titled—a life haunted by the presence and constant return of the past. The ghosts of the past re-emerge in this eternal present, continuing to play a role in the contemporary; they allow us to analyze it, recontextualize it, re-determine it.

The ruins of the West take shape as a stratified psychic landscape, fragments of a collective unconscious never fully addressed, still pulsing beneath the surface of the present. In this sense, the Mediterranean—elected as the cradle of the hegemonic West—becomes a hauntological place, where the past is not simply preserved but persists as a spectral presence that informs and deforms our present enabling the emergence of historiographies and narratives that have been crushed and erased by dominant ones.

“The work of this ‘becoming-minority’ has to do with the assumption of a previously repressed level of conflict,” which, in this specific case, allows for the transmutation of the object of history into the subject of history. In the haunted present, we can find the breaking and overturning points of hegemonic relations of dominance and subalternity, already widely described by Gramsci in his La Questione Meridionale, which took form in the North-South power dynamic at the time of Italian unification in the shape of a subordinated and subjected South to the interests of the North.

However, North and South are not only two coordinates on the Italian map, or more broadly on the earth map, but represent two different narratives of modernity, two ways of being in modernity—and since colonialism constitutes modernity itself, this conflictual power relationship sees in the emergence of southern subalternities the way to confront, understand and deconstruct colonialism, both past and present. The Global South is not just a geographic location but represents all those places crushed into a subaltern role by the dominant narratives of history. Places that present to the world other histories, other cultures, allowing the challenge and overturning of preexisting power roles, and thus the resistance to and evasion of colonizing modernity.

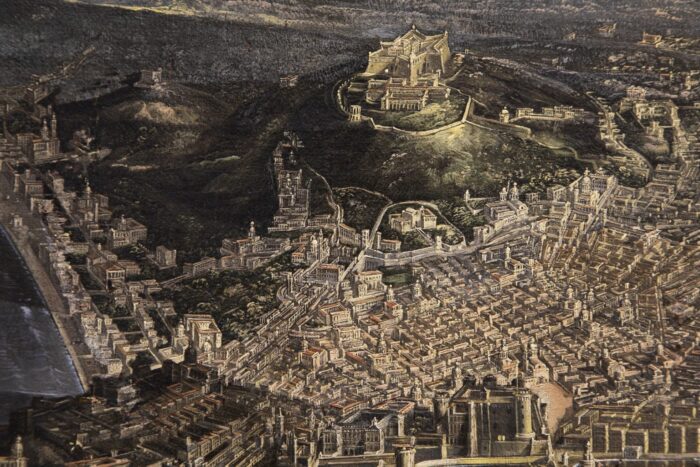

In this context, Naples—invaded but never subordinated—emerges as one of the crucial nodes in the southern narratives of the Mediterranean. Naples as a sedimentary city, which receives, translates, and reshapes the various cultures that pass through it, always returning a properly Neapolitan version of them. Lands long considered discardable, non-places without hope and thus without a future—and it is within this ecology of discarded elements, flattened onto the present, that Naples has always built its own conflicting narratives challenging the imposed ones.

Naples, then, as a place of translation and transformation of different histories, different cultures, a place in constant mutation. A continuum of hybridization and creolization that, as Chambers has pointed out, manages to offer its own version of modernity, of how to be modern, how to be Neapolitan, how to be part of the modern world—but on its own terms.

It is from this scenario—from one of these Souths, from Naples—that the interview with Iain Chambers took shape and unfolded, aiming to address and delve into some of the key themes of his studies on the Mediterranean, focusing especially on his ideas regarding the use of music as method to escape dominant narratives and propose new critical orders for analyzing and interpreting the past and the present in order to construct new futures.

“Sounds contest the colonization of time, space, and language, because they transcend those frames, those borders, those frontiers, proposing other Mediterraneans sustained and suspended within the sounds themselves.” From that we pass through some interesting concepts such as the dubbing of history and decolonial melancholia in a long conversation that points out two main questions: starting again from the South—or, better, from the Souths—to escape the reactionary and colonizing present? Or rather, who has the right to narrate the Mediterranean?

Giovanni Napolano: If it is true that “the events of the world do not line up like the English. They crowd together chaotically like the Italians,” what role does chaos play in the nonlinear and anti-hegemonic narrative of the Mediterranean?

Iain Michael Chambers: Rather than thinking in terms of chaos, I think it’s important to think of the Mediterranean as a stratified and sedimented reality that produces patterns, often unruly patterns, but that propose another way of thinking, both its histories, its cultures, its materialities, in a non-linear fashion. In other words, not all the materials that we have encountered in the Mediterranean, whether cultural materials, whether music, language, everyday life, can be reduced to a single accounting of time and space. So it is these patterns which interrupt or interrogate the existing or the dominant definitions that tend to be given to the Mediterranean, as though it’s a unique and homogeneous reality that can be rendered transparent by critical language or by political action or by cultural definitions and transformed into a chronology of linear causality.

You argue that the visual, musical, and literary arts provide us with different languages through which we can map and bring forth a Mediterranean that escapes a monothematic definition, confined to academic and disciplinary logic, in order to propose unexpected and innovative critical orders. Could you elaborate on this concept?

So the idea that the visual arts, musics, literature, poetics provide us with languages, or better unauthorised grammars, with which to critically understand, speak and map the Mediterranean is to do with the very nature of how they activate language, how they activate our senses, how they activate our bodies and movement in this geo-philosophical space. And because they’re proposing a sort of an excess which is not simply tied to the idea of forming a rational communication but rather proposing a communication where poetics suggest the excess of language and its opaque possibilities. This is something that more rationalising procedures, whether it’s sociology or anthropology or historiography, will exclude because those disciplines always seek to conclude with some sort of definition or a set of conclusions that serve to freeze and frame the present and its past. The visual arts, music and literature are about undoing that past, and a desire for a transparent present and re-proposing them in unexpected ways to provide us with other ways of looking and listening to the Mediterranean and its ongoing formation. This is to propose another form of history, a history which is not merely a discipline but one that is attentive to the possibilities and potentialities of the languages we inhabit and the languages that form us.

So we can begin to talk about, I don’t know, music or the history of music or the history of the visual arts and turn the terms around and say that what we have here is not the history of music but music as history or the visual arts as history. This move is obviously not recognised by institutional understandings and procedures but they exist, persist and resist to propose wider horizons that take us into deeper waters where the Mediterranean, which is above all an aquatic reality, allows us to travel much further afield than the disciplinary logics that pass for knowledge in the institutional world.

The Mediterranean as a geographical space of perpetual transition, exchange, and movement. Despite its heterogeneity, and stratification, would it be correct to study the Mediterranean through a concept of historical-cultural “continuum” and why?

Well, of course, there is a continuum in the Mediterranean, represented by the passage of time and the constancy of its material profile, but it is also a site of discontinuities around historical and cultural movements that interrupt any simple idea of an unfolding of time in a linear fashion from the past through the present to the future. And, of course, these discontinuities operate at different levels. They can also be geological and can also involve non-human actions. But when we talk about continuity and discontinuity, we tend to talk about it in terms of social forces and historical combinations. So, if we think about the Mediterranean, even over the last 1,000 or 1,500 years, we have to register there have been major discontinuities with respect to an understanding that sees the Mediterranean as a unique or homogeneous entity, which we still tend to evoke to when we think about the Mediterranean and the sea itself as Mare Nostrum. This is all part of an inheritance from the Roman Empire, and has continued all the way through to the present with the understanding of the Mediterranean as somehow European property.

All of this has been accentuated over the last 200 years through the impact of European colonialism worldwide and in the Mediterranean itself. To be more critically honest and more attentive to historical detail, we would need to recognise that the Mediterranean has also been viewed and framed and explained through other perspectives related to other histories that have crossed and inhabited its spaces, whether we’re talking about the Arab expansion in the 8th and 9th centuries through the Mediterranean and into southern Europe and Central Asia, or referring from the 1500s onwards to the Ottoman Empire, that was the most powerful entity in the Mediterranean (and Europe) at that time. And then there is the question of how the Mediterranean itself is transformed by being resituated in a planetary reality after the so-called discoveries of the Americas, and so on.

So the Mediterranean has underlying continuities, but at the same time there is a set of discontinuities in this continuity. So that allows us to think about different rhythms, different patterns, which are in the interrelationship between certain apparently fairly fixed, stable elements, socially and above all materially, and the historical movements in and through the Mediterranean, which makes it a particularly complex reality given that it is where Africa, Asia and Europe interlace and combine both in antagonisms and also in proposing new, shall we say, creolised or hybridised cultural realities. So the Mediterranean, even the modern Mediterranean, cannot really be thought of without also registering the importance of Islam and Arab culture in its making, even though today this is constantly denied, but it is central to our mathematics and the digital architecture of the computer. Algebra, the decimal system and the significance of zero were all brought to Europe by the Arab world, much of which was transmitted from Hindi mathematics. It was resisted in Europe for a further 600 years before what we call Arab numbers (actually of Hindi-Arab provenance) were finally adopted.

So all these elements suggest an idea that there is not simply a continuum, but an intersectional space which is crossed, folded and reassembled by social movement and forces. Even though many elements are constant they change through time as part of historical cultural processes and, as such, are always open-ended and subject to modification, to change.

In the rewriting of Mediterranean readings, in my opinion, the rediscovery of the role of the city of Naples as one of the crucial crossroads of this narrative remains fundamental. Naples as a colonial city, not a conquered one, invaded but never subordinate. “Sedimentary Naples” should be observed within an ongoing historical continuum in which different peoples and cultures have passed through the city, leaving traces that the city itself has made its own by transforming and incorporating them. Tell us about Naples. What role has it played and continues to play, in your opinion, for the new southern narratives?

And of course, what I’ve just said about discontinuities in the Mediterranean continuum, can also be applied in a more precise fashion when thinking about the city of Naples, where we have, again, stratification, and the sedimentation of multiple histories that have become part of the city, part of its making. Again, it is to understand that there’s not simply a fixed or stable tradition, but different cultures, different histories that traverse the city and come to be transformed and translated in order to meet local concerns and needs. The transformation works both ways, both on the city and on the languages of translation. Again, it is an understanding of how to consider Naples not simply as a homogeneous continuity with an autochthonous tradition to which external elements are sometimes imported and added, but as a site of transformation and translation.

And we could think about that in very obvious musical examples. Thinking with the music that was produced in the city in the 1970s, 80s and 90s, we find musical forms that are clearly not of Neapolitan origin. With the music of Pino Daniele, we have a strong presence of Afro-American blues and Black music that is deployed as a basis for transforming and translating the local tradition of Neapolitan song to produce a new way of sounding the city. In this sounding out the city, there emerges a music which is Neapolitan, but at the same time draws upon “foreign” elements to renovate and renew local traditions. In other words, tradition becomes the site of translation and transformation. We could also think of this when listening to the sounds of the Neapolitan group Almamegretta, where we have the Caribbean, the music of Jamaica, reggae music, dub music, arriving probably via London, in Naples and being transformed into a very specific Neapolitan sound, where of course we have Raiz who sings in Italian, but also in Neapolitan, over dub rhythms, while insisting on Neapolitan specificity. So, these local sounds are drawing upon, translating and transforming sounds—that are never simply sounds—in a series of cultural and historical proposals drawn from the planetary presence of the Black diaspora in African-American musics.

I think it’s important to understand this; that is, of how Naples itself is not somehow fixed and stable, but is rather a mobile site of encounters, of creolisation, hybridisation, and that’s what permits it to know its own way (to quote Pino Daniele) as a vibrant cultural and historical reality. Here I think Naples is particularly important in the Italian national context, as it has in many ways proposed a more open and a more complicated relationship with what is called modernity. It manages to propose its own version of how to be modern, how to be Neapolitan, how to be part of the modern world, but on your own terms. It offers a very different take to that of the cities in the north of Italy, that tend to ape or imitate what’s happening north of the Alps, in Paris or Berlin, London, or of course across the Atlantic in New York and Los Angeles, Naples in a sense manages to put its own distinctive spin and signature on these multiple musical and cultural flows.

So I think it does propose a different version, a different way of being in modernity without simply being a replica or bad copy of what is being produced elsewhere. It has its own originality in this story.

Why is the analysis of Mediterranean cultures, not as static cultures but as continuously evolving, still central? How does Naples, especially through its music, fit into this process?

Well, I think I have already answered this question about how Napoli is part of the ongoing historical configuration, reconfiguration and re-elaboration of the Mediterranean, talking in particular about its music. But it’s of course an invitation to always think about how a city or urban space is not given, but is always socially and historically produced. So as such, it is always in a process of becoming, and this applies to all its languages.

And this I think is very important, for it breaks away from a sort of static geographical understanding as though locality is fixed in time and space, and invites us to think about how locality, in this case the city of Naples, is produced, is socially and historically produced, and therefore is always open-ended, is always part of the historical processes in play. And this of course is a way of insisting that as a social and cultural and historical product it cannot simply be reduced to a map, or to local governmental procedures and plans, or the architectural dreams of rendering space completely rationalised. So I think it’s this uncertainty, ambiguity and open-endedness in a city, in all cities, which in Naples takes a particular form drawn from the complex cultures that are entwined in its making.

And that includes cultures which are not simply European, but also come from the African and Asian shores, thinking, for example, in terms of the centrality of the Arab world, Islam and the Ottoman Empire, to the making of the modern Mediterranean. So all that is in play, and I think we can also hear it in its sounds, in the music, in the way people sing, how they sing, the tonalities of the voice, and even in the cadence of the dialect.

Sounds allow us to escape the colonial narratives of the Mediterranean. Music can become a critical device and provide us with a sociology and historiography in which subaltern cultures, often overlooked in academic narratives, are suspended. Since colonialism constitutes modernity itself, how can the Mediterranean and its music allow us to reinterpret and rewrite modernity? How much can the Mediterranean help us think about a present and future after the collapse of the West?

Well, the idea that sounds allow us to flee or escape from national and colonial narratives of the Mediterranean is obviously tied to the very nature of music itself, which travels without asking permission or without holding a passport, exercising its power to move across national boundaries and be appreciated without necessarily without having linguistic competence. Our body responds to sounds. I’m particularly thinking of the centrality of dance in Mediterranean music, long before we seek to provide a meaning or put into words what the sounds might be conveying, or the lyrics of the song. We respond before all of that. So to think with music in some way as being inherently always transnational undoes the idea of disciplining or reducing it to a national narrative, or explaining it purely in disciplinary manners, such as the sociology of music or the history of music. There’s always something more happening there.

And that’s why it has a particular force, and once referencing the planetary centrality of African American music, it has a particular force to provide voice or space for cultures which have been negated and refused, thinking of course of Black diasporic life within modernity, of ex-slave cultures in modernity and the music that they have produced. And then in the Mediterranean itself, thinking with those cultures that have always been subordinated, rendered subaltern to a particular version of modernity, while seeking to escape local confines and the idea that subaltern cultures are not modern, and are therefore not to be included in the narrative. So the sounds are always contesting the colonisation of time, space and language, because they’re exceeding those frames, those boundaries, those borders, proposing other Mediterraneans that are sustained and suspended in the sounds themselves. These histories are suspended in the sounds themselves. Such histories which the sounds sustain allow us to return to and reinterpret modernity in a manner which is not necessarily recognised nor authorised. This allows us to think about modernities sustained in music which are not simply the property of the hegemonic culture or of the West, but in fact circulate in the world proposing openings and new possibilities not foreseen by official or institutional culture.

In analyzing music as a method to propose new critical orders challenging modernity, you use the concept of “dubbing” as a technique that allows the subaltern narratives to take elements belonging to the dominant narratives to then re-contextualize them, re-purpose them. Could you elaborate on this concept and the parallel with dub music?

So, the idea of music as method, and connected to that is the idea of dubbing, borrowed obviously from Jamaica, reggae music, and the dubmasters in Kingston, and then taken up, as I’ve mentioned, by a group such as Almamegretta, here in Naples. The idea is that it takes elements which are already available that are then remixed and recombined, so it becomes a sort of method of thinking about music with music. But it not only involves music. It also proposes a manner for thinking about culture and history, our sense of belonging, or so-called identity, how you collect and put together elements that are already available, in circulation; that is, cultural and historical elements that you assemble to meet your immediate needs and circumstances. So, to dub is basically to use the materials already in circulation and stitch them together in a manner which produces a new rhythm, a new set of sonorial, and with them, cultural and historical possibilities.

It is not simply a technique achieved in the recording studio. It is also a social, cultural and historical performance that elaborates a sense of belonging, an identity, in the ongoing mobile processes of historical becoming. This can then be applied to thinking about how subordinate cultures operate as they appropriate elements which are often imposed by official culture, institutions and religion, and then rework them. For they repropose and re-purpose those languages to say something unexpected, not authorised by the imposed languages.

Think of the centrality of religion to the Black diaspora and how Christianity, for example, was cut up and rearranged in such a manner as to express the conditions and inheritance of being a slave, of being black in a white supremacist society, which then produces the music of gospel, blues, R&B, hip-hop, rap, and so on. So, this is the idea of dubbing. It’s basically taking elements already available, repeating them in a new assemblage, putting them together so that they produce something unexpected and new, which permits those dubbing modernity to find a way of negotiating their way through the world.

Speaking of subaltern cultures, you wrote a book, La Questione Mediterranea, which takes the title from Gramsci’s text La Questione Meridionale. Could you explain the parallel and why Gramsci’s thought remains fundamental for a historical-socio-cultural rethinking of the Mediterranean?

Yes, the idea of a Mediterranean question, the title of a book I wrote with Marta Cariello, which is coming out in English this year, is obviously drawn directly from the famous essay written in 1926 by Antonio Gramsci, La questione meridionale, the southern question. At a simple level it seeks to expand Gramsci’s mapping of a national question, the relationship between northern Italy and southern Italy where the south is subordinated and subjected to the interests of the north in the moment of unification, and to extend it on a wider map. This allows us to think about the asymmetrical relations of power between the north and the south on multiple scales. We refer to the northern shore of the Mediterranean, the European shore, and its modern exercise of power over its subordinated and subaltern African and Asian shores sustained through unequal relationships of economical, political, and cultural power. This poses the question of who has the right to narrate the Mediterranean. Clearly, over the last 200 years it has been Europe that has framed the Mediterranean according to its interests and perspectives. So Gramsci’s conceptual framing is central. For it shows how geographical relations are also historical and political ones. Maps speak of power. They cannot be viewed as simply neutral and scientific. This permits us to consider modalities that lead to interrogating and undoing those maps, tearing them in a way that allows other histories, other cultures, to come through. So, the maps are not simply waiting to be turned upside down. It is not simply a question of reversing the relationship between north and south and insisting that the souths of the world have their rights, and therefore the north must be reevaluated. What is being proposed is rather the exposing of the very premises of power that permit a certain situation to establish the power to map and narrate; that is, propose a certain geography and history. North and south in Gramsci’s case was also between the north of the world and Italy, on what lay the other side of the Alps: modern industrialised Europe with its so-called progress and modernity. This also leads to understanding today of the relationship between the north and the multiple souths of the planet. Here we can begin to see that Gramsci’s argument is not simply a local argument about Italy. It becomes an argument about planetary relationships of power. This allows us to bring into play these other histories, other cultures and understanding that they being refused, negated is part of the composition of understanding the modern world through the filter of power. All of this dismantles existing understandings of geography or history as neutral exercises in mapping or involving a critical distance from events to provide a seemingly neutral account of spacetime. In other words, there is no neutrality but rather an exercise of powers and the understanding of your position in their configuration. If you find yourself in one of the souths of the many souths of the world, which may be southern Italy, the southern shore of the Mediterranean, or elsewhere, it proposes a different way of understanding history, culture, and considering how they are held together and sustained in asymmetrical relationships of power.

Amidst the ruins of a now lifeless West, sounds seem to survive the general collapse. Sounds that, like ghosts, reappear from the past and make themselves present in the dense and heterogeneous network that shapes the cultures of Mediterranean cities. Would it be correct to speak of Mediterranean hauntology?

Well, of course, sounds, as I said, sustain histories and so their reverberation haunt or ghost the present. We can certainly talk about a ghosting of the Mediterranean that is sustained through music, consistently proposing an open and seemingly intangible archive. Also because the means we use to access the past are always contemporary, whether it’s CDs or streaming or whatever, there is always a contemporary moment in the retrieval of a past that lives on in the contemporary technical means that allow us access those archives that continue to ghost our present.

It’s also a way, of course, of opening up the present so that it can be interrogated and traversed by sounds that, even though they may have been recorded 50 years ago or maybe written 400 years ago, return us to the present through a folding, doubling, dubbing and ghosting of time. We are not only listening to, or playing, a composition but are also involved in a recomposition, a recomposing of the present through the past which continues to interrogate us in the present like a ghost that refuses to fade away. So it is most certainly a case of thinking with the sounds of the past, the sounds of the dead, that refuse to pass away and continue to ghost the present and refute the possibility of closure. In the same manner, we could consider contemporary migration where migrants are also the uninvited ghosts who bring into the present a colonial past composed through racialised discrimination and oppression and which refuses to fade away, to die and so continues to insist on the colonial constitution of the present.

These are just two examples of Mediterranean hauntology. Those folds in time where chronologies and ideologies of linear progress are disrupted and deviated precisely by what their powers seek to repress and eliminate. Coming out of the past with histories and questions that the present is unable or refuses to answer, music and migration are proposing other, still unauthorised, futures

Could you elaborate on the concept of “Decolonial Melancholia”?

The idea of Mediterranean melancholia points to how the hegemonic world—the north, Europe, the West —refuses to register this altogether more complicated and turbulent series of pasts in the present. We can see this right now in the Mediterranean in the superficial rhetoric and historical vacuity with which genocide in Gaza is discussed in Occidental politics and the mass media. It leaves us in a state that Sigmund Freud would have referred to as being blocked in an understanding of the present which fails to work through the historical trauma that is our inheritance. Melancholia is the response to the failure to work through this more complicated, disquieting past that continues to disturb and traumatise the present. This is the failure to acknowledge that critical space sustained by the ghosts of the past. The colonial constitution of the present is repressed by an ideology of linear time and progress that considers colonialism past and gone, so that the colonial processes that sustain us need not be confronted. What blocks is the refusal to recognise that modernity itself is a colonising apparatus. Gaza, Israel and the question of Palestine is simply the extreme profile of this precise history, our history. So I would suggest that the state of melancholia emerges from white Occidentals refusing to face and take responsibility for the past. It means to remain blocked in a state that leads to frustration, fear, anger, despair and resorting to racist rage. To give up the lost object of Europe at the centre of the world, would be to work through and consider another arrangement of powers, histories and cultures that do not simply reflect Occidental narcissism and needs. This means to understand that the Mediterranean is not only ours. It is not only ours to narrate, to define and to manage. So our melancholia points us to the refusal of this emergent state and leads to what we might simply call a beleaguered white supremacy.