May You Live in Complexity

A walk through the Venice Biennale

The 58th International Art Exhibition, titled May You Live In Interesting Times, is curated by Ralph Rugoff and organized by La Biennale di Venezia chaired by Paolo Baratta.

An evening during the opening days of Venice Biennale, at one of the dozens of openings spread throughout the city at every hour, I was having a chat with a friend. We were joking about how bizarre is the fact that one of the most important events of the art world takes place in a city like Venice. Half sea, half land, with no possibility to go quickly from a place to another. You better not forget your sneakers, because you will have to count on your feet, and Google Maps will not be able to help you while you’re getting lost in the narrow alleys and sotoportego. “Why not Milan?!” he said, laughing. Yet, despite runnings and spaces almost always too crowded, Venice keeps a secret of magic. You’ll maybe perceive it just as a brief sparkle, while you’re walking along a canal or seating in a campo. In an article I happened to read a couple of days ago, philosopher Paul B. Preciado says “the whole city stands erect, like a drag queen, on the fragile stilettos of its foundations (…) on a land where it is inappropriate to establish a city, it is there that the wonder has been built. Venice is the city outside the norm, indeed the place where the rules of life must be abolished and reinvented.”

With the current International Art Exhibition, Venice Biennale arrives at its 58th edition. 79 artists, 87 national participations and a number of collateral events. First thing worth to highlight is the large presence of female artists (finally), amounting to almost half of the participants in the main exhibition curated by Ralph Rugoff. The title proposed is May you live in interesting times. Inspired by a fictional proverb, a curse, supposedly coming from China, but actually made up by Western Culture—a case of orientalism, that recalls the fake news phenomenon and, more in general, all the ambiguities we witness in the so called post-truth era we are living in. In addition to the threatening tone of the sentence itself, the premises of the exhibition might seem to open a definitely negative view on our times.

Mari Katayama, Various works, 2011-2017. Mixed media. Photo Italo Rondinella. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Mari Katayama, Various works, 2011-2017. Mixed media. Photo Italo Rondinella. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

But, a shift in perspective may allow to see things in a different light. “This kind of uncertain artifact suggests potential lines of exploration that are worth pursuing at present” as Rugoff suggests, uncertainty becomes a positive value when it fosters critical thinking and helps mining superficiality and revealing the complexity of reality. While reading Rugoff’s introduction, something that the Italian poet Chandra Livia Candiani said came to my mind, about the power of uncertainty and the importance of learning to inhabit fragility. She explained this to her students using two martial arts stances as a metaphor: there is a classical posture with bent knees, both feet and entire body rooted in the ground; then there is also the posture with open arms and only one foot on the floor. You will probably feel your body starting to sway. Do listen to that vibration because there is where the threshold of knowledge is placed.

So, this is what art should do, it should escape easy conclusions, open up things, raise questions, expand interpretations, create dialogue. It is necessary to move back to the moment we seek for the truth, not in the answer, but in the process. Art should help questioning obsolete and harmful habits of thought, challenge traditions and rethink categories. The artists featured in Rugoff’s exhibition have been selected because they place themselves in a borderland: most of them use different media, adopt hybrid practices and genres, draw elements from various cultures; many show a speculative attitude in their research. The framework outlined by the curator is in any case very extensive, and the artists have approached it in the most diverse ways.

Rugoff has divided the exhibition into two independent and parallel shows: Proposition A, in the Arsenale, and Proposition B, in the Central Pavilion of the Giardini. All artists are present in both. The two shows are conceived as possible declinations of the dialogue between the artists and the curator, suggesting that there could have been many potential others, and they propose two different aspects inherent to the practice of each artist. The balance between paintings, videos, sculptures and installations is well thought throughout the two itineraries, but the exhibition in the Central Pavilion at times seems to lose the sense of an overall look, as an orchestration that connects one work to another. The set up in the Arsenale looks instead better structured, also thanks to the division and organization of the space with plywood panels. The curator has worked on the texture, trying to create separate areas to focus on, and the presence of large rooms dedicated to single big installations, linked by a somehow similar sensibility or common topics, gives rhythm to the visitor proceeding through the exhibition. Indeed, many of the exhibited artists are focusing on major issues of our times such as climate change, conflicts, marginalization, racism, impact of technologies, gender-based violence and discrimination. Known problems, fresh gaze..

Among other remarkable pieces, in the beautiful three channel video installation of Korakrit Arunanondchai, realized in collaboration with Alex Gvojic, No history in a room filled with people with funny names 5 (2018), part of a series started in 2013, different stories flow on the screens and end up melting in the eyes and in the head of the viewer. News stories, private scenes involving the artists’ grandparents, powerful views of Thailand landscape and nature, the dance of the artist and performer boychild, whose visceral and mesmerizing movements seem to evoke the presence of an ancient divinity. Arunanondchai weaves different threads and develops a reflection on the history and culture of his country, the progressive change it is experiencing, the control exercised by Media and by government structures.

Teresa Margolles, La Búsqueda (2), 2014. Intervention with sound frequency on three glass panels. Photo Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

Teresa Margolles, La Búsqueda (detail), 2014. Intervention with sound frequency on three glass panels. Photo Italo Rondinella. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

Teresa Margolles has received a special mention for La Busqúeda, a work she realized in 2014 that deals with the tragic reality of feminicides in Mexico. Three large sheets of glass show some torn posters, announcements reporting disappeared women. A low frequency noise make the glass tremble to the sound of a train that the artist recorded near the border between Mexico and the United States and then manipulated.

Feminist issues also animate the research of Frida Orupabo and Zanele Muholi, who both work with personal archives of images to explore gender and race. Orupabo’s collages and videos investigate the representation of the black female body in mass culture, combining materials from TV, cinema and advertising, while artist and activist Muholi presents a group of self-portraits from an ongoing series. In these works she offers herself to the viewer, as woman, black person and lesbian. The giant format of the photographs in the Arsenale gives the portraits an assertive force, while the smaller format of the works in the central pavilion allows a more intimate relationship with the images.

Michael Armitage, Various works, 2019. Oil on Lubugo bark. Photo Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Michael Armitage, Various works, 2019. Oil on Lubugo bark. Photo Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Michael Armitage, Various works, 2019. Oil on Lubugo bark. Photo Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

The paintings by Michael Armitage exhibited in the Arsenale combine different sources and references, from African mythologies to current events. He dialogues with the European masters of Post-Impressionism, to crack the exotic view of his land delivered by them to Western culture. He also presents a series of ink-made papers in the Central Pavilion of the Giardini. Inspired by the documentation of political agitations occurred during the elections held in Kenya in 2017, these monochromes show single figures isolated from a context, floating in a state of surreal suspension on the white pages, with an incredible expressiveness.

The white album, the new video realized by Arthur Jafa, who won the Golden Lion, explores themes such as racism and white suprematism, hate and love, combining found footage with intense portraits of white people close to him. The rhythm of the video slows down and the viewer’s gaze gets lost in the close-ups on these people. Suddenly, one comes to realize that it is time to let go old certainties and build new alliances.

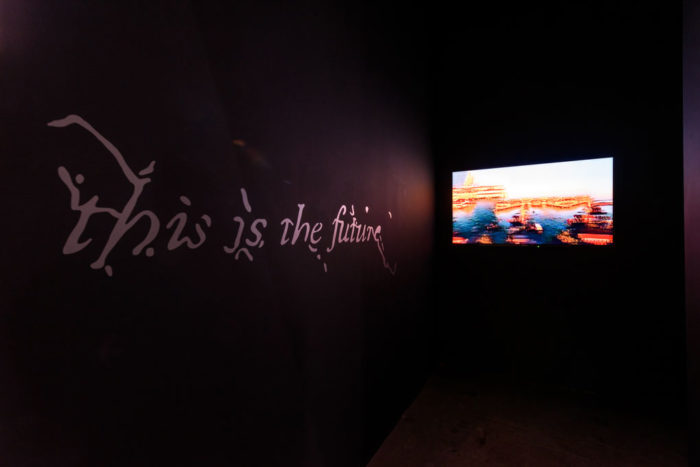

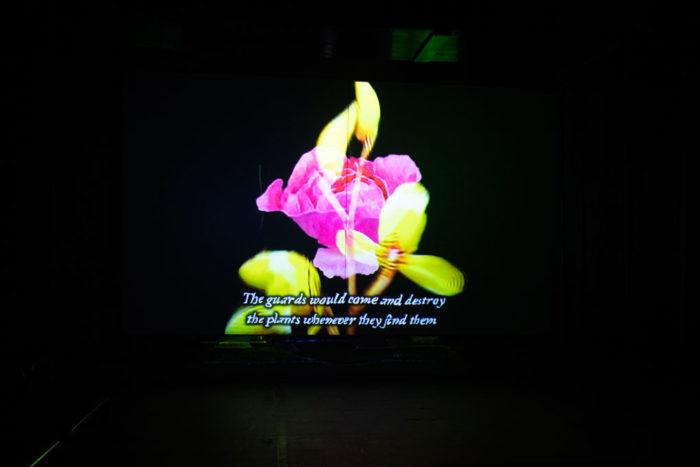

It seemed that many of the artists’ intention was to lead the visitors into parallel realities and other worlds.Both Ed Atkins and Hito Steyerl present two immersive multimedia installations in the context of the Arsenale. This is the future (2019) carries on Steyerl’s research around the applications of AI and its implications in contemporary society. While one can walk on platforms through a digital flowers’ garden, the artist narrates a utopian story of impossible predictions of possible futures, to finally lead us back to reflect on present times. Instead, with Ed Atkin’s Old Food (2017-2019) the visitors enter a dark pseudo-historical world, in a space cramped by huge stands full of stage costumes. Fake information boards written by anonymous critics scattered everywhere are parodying institutional authority. In the videos we see CGI characters crying desperately, groups of people blowing up in the air, sandwiches made of human bones and books.

Hito Steyerl, This is the Future, 2019. Mixed media. Photo Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Hito Steyerl, This is the Future, 2019. Mixed media. Photo Italo Rondinella. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Disasters under the sun (2019) and Dream Journal 2016-2019 (2019) by Jon Rafman depict dystopian realities made of hallucinated visions, that question our relationship with technology and violence, both acted and witnessed. A dystopian vision of a dark future is also proposed by ESKALATION (2016), a big installation by Alexandra Bircken, with 40 black figures hanging from tall ladders climbing up to the ceiling of the Arsenale. With Endodrome (2019), Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster offers the visitors the opportunity to experience another space-time dimension making use of virtual reality.

Despite not having the visual impact of these large installations, a group of photographs and paintings provide some of the most profound moments of the exhibition. For instance Angst (2013-2017) by Soham Gupta is a series of nocturnal and incredibly vivid photographic portraits depicting some inhabitants of Calcutta, the outcasts. The power of these works derives from the fact that, through the faces and stories of these people, the artist unveils something that concerns us all: our vulnerability in being in the world and yet the strength that allows us to go through every single day. They made me think of T. S. Eliot’s words on the characters of Nightwood by Djuna Barnes: “The miseries that people suffer through their particular abnormalities of temperament are visible on the surface: the deeper design is that of the human misery and bondage which is universal. In normal lives this misery is mostly concealed; often, what is most wretched of all, concealed from the sufferer more effectively than from the observer.”

Soham Gupta, Untitled from the series Angst , 2013-2017. Archival pigment print. Photo Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Also the paintings presented by Nicole Eisenman in the Central Pavilion really capture the eye. They speak of our age, bringing the attention on issues related to queer identity. I couldn’t stop looking. Born with a rare genetic disease that shaped her physicality, Mary Katayama puts her body at the center of her photographic work. Her elegant images open visions that undermine the normativity that regulates the conception of the body in our society. Acts of appearance, instead, is a project started in 2015 by Indian artist Gauri Gill. It shows a series of shots depicting figures wearing papier-mâché masks made by indigenous artists, set in the city of Jawhar. Their striking sincerity arouses the curiosity of those who observe them.

The attention on the issues of our contemporaneity characterize also many of the proposals made by the artists who represent single countries in the Pavilions. For example, the two protagonists of this Biennale, the Lithuanian pavilion, winner of the Golden Lion, and the Belgian pavilion, which received a special mention, similarly propose a choral representation of the human condition and of the dangers threatening our society, but with diametrically opposed sensibilities. In Sun and sea (Marina), the artists Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė and Lina Lapelytė set up a scene full of poetry, an opera-performance that takes place on an artificially lit beach in one of the buildings of the Marina Militare, ten minutes away from the Arsenale; visitors observe from above a crowd of bathers engaged in lazy activities, singing everyday songs, “songs of almost nothing.” But the small private concerns told by the performers slowly insinuate themselves into the consciousness of the visitors-voyeurs, bringing to the surface more serious questions, about climate change and the suffering of the earth making the initial apparent serenity of the scene suddenly crack.

Pavilion of LITHUANIA, Sun & Sea (Marina). Photo Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Pavilion of LITHUANIA, Sun & Sea (Marina). Photo Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Pavilion of LITHUANIA, Sun & Sea (Marina). Photo Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

On the contrary, there is no room for poetry in the world set up by the Belgian artist duo, Jos De Gruyter & Harald Thys: their project depicts with black humor a society of automatons, where tradition appears the macabre refuge of a culture in crisis, that of the Western countries. In the central hall of the pavilion, some mechanized puppets dressed with traditional costumes carry out craft activities; a woman knits, a man sharpens knives, another works a dough with a rolling pin; the side rooms of the pavilion are closed by gates behind which other characters are imprisoned, the wretched. There is no moralism or judgment in the eyes of the artists, and the visitors are left to make their own considerations. I had to think of the rise of right wings and nationalist parties in Europe, their claims in defense of traditional values, and wondered how far this Middle Ages is from us.

Pavilion of BELGIUM, Mondo Cane. Photo Francesco Galli. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

The Ghana Pavilion, which marks the country’s first participation in the Biennale, proposes a group of six artists of different ages and working with various media, and provides an overview on the situation of the artistic research in the country, making considerations about what the contribution offered by arts to present times could be. It succeeds in building a complex imagery that talks about the history and culture of the country. The 3 channel video installation Four Nocturnes by John Akomfrah is stunning, as well as the paintings by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

Pavilion of GHANA, Ghana Freedom. Photo Italo Rondinella. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Pavilion of GHANA, Ghana Freedom. Photo Italo Rondinella. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Compared to the rest of the Biennale, where one always has the perception of time passing by, sometime even at accelerated speed, the English pavilion distinguishes itself for its atmosphere of temporal suspension. Cathy Wilkes sets up minimal environments in pastel colors, a few elements scattered here and there, dried flowers, small genderless figures with swollen bellies, glass plates and pitchers, some landscape paintings in livid colors. The almost empty spaces speak of lack and loss, as if they were interior spaces, psychological landscapes. At first it seemed out of context in this Biennial, but then I thought of it as a good occasion to bring back the attention within us, just for a moment, in order to better understand what happens outside.

Neither Nor: The challenge to the Labyrinth is the title of the Italian Pavilion, that presents an heterogenous group of works by artists Enrico David, Chiara Fumai and Liliana Moro. Entering the Pavilion, the visitor faces the opening of a labyrinth. As clarified at the entrance, everyone is free to build their own path and, consequently, to define the exhibition through their choice. One doesn’t have to see all the works, and so every choice is the right one. The structure is massive, actual walls alternate with high curtains and walls made of mirrors. Scattered among these partitions, sculptures, wall drawings, installations, sound pieces and display cabinets with every kind of objects inside. While the metaphorical concept of the labyrinth seems to respond effectively to the theme of the Biennale, perhaps, there is more emphasis on the play on this extended metaphor than on the individual artworks themselves. The voices of these beautiful works seem to struggle a little to connect with each other in these lanes, and perhaps they do not find enough space to activate and expand their meanings and potential.

Pavilion of ITALY. Photo Italo Rondinella. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Pavilion of ITALY. Photo Italo Rondinella. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Pavilion of ITALY. Photo Italo Rondinella. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Last, it is worth mentioning two among the official Collateral Events, 3x3x6 by Taiwanese artist Shu Lea Cheang, and Scotland + Venice, that presents the new video by Turner Prize winner Charlotte Prodger. In the setting of a series of rooms of the Palazzo delle Prigioni, a former prison just behind Piazza San Marco, Shu Lea Cheang reflects upon structures and implications of high-tech surveillance techniques and presents ten case studies of people who were accused and incarcerated because of reasons related to gender and sexual orientation and behavior, both in the past and in present days. The show includes installations and videos, and opens complex questions about the strategies and technologies employed by society to control our private lives and our bodies, and how those influence the definition of our identity, establishing what is right and what is wrong for us. It is impossible not to think of the abortion ban that has been just approved by the government of Alabama. Middle Ages, as we mentioned earlier.

SaF05 is the title of the new work by Charlotte Prodger, who has been called to represent Scotland. The video is the last chapter of an autobiographical trilogy, that includes Stoneymollan Trail (2015) and BRIDGIT (2016). Shootings of wide landscapes flow on the screen one after the other, accompanied by the artist’s voice, which narrates diaries and thoughts of her private life. This 39 minute video is probably one of the most intense and touching moment of the Biennale, the artist’s words lead the viewers across an emotional journey, during which the landscape progressively undergoes a metamorphosis, the barren grounds dotted with shrubs and the rocky surfaces so turning into living skin of desiring bodies. The title SaF05 comes after the name of a maned lioness, a rare animal that embodies the artist’s unravelling around identity issues and the nature of desire.

As remarked by the President of Venice Biennale Paolo Baratta, the Biennale exhibition should be “an instrument of knowledge, imperfect yet dynamic, able to navigate complexity.” It was probably inevitable to give up some of the coherence of the curatorial presentation to embrace the complexity of our times. There may be various opinions on the success or failure of this biennial from a formal point of view, but it has undoubtedly built a space and a chance for art to question reality, and for us to question art’s possibilities of being part of our times as a proper critical tool.