Marching on the Museums

“National” History and state power

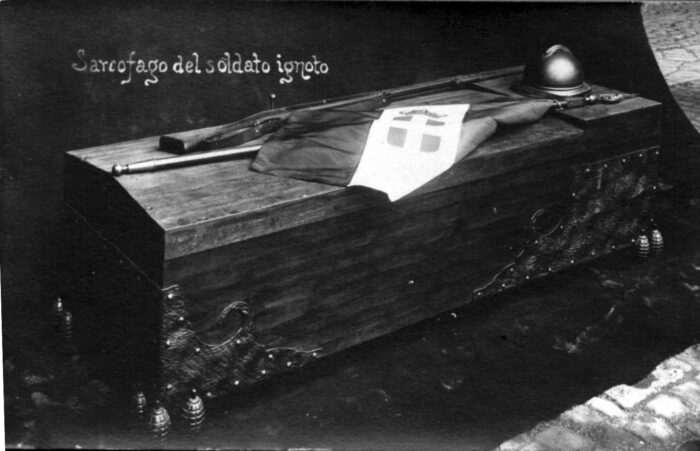

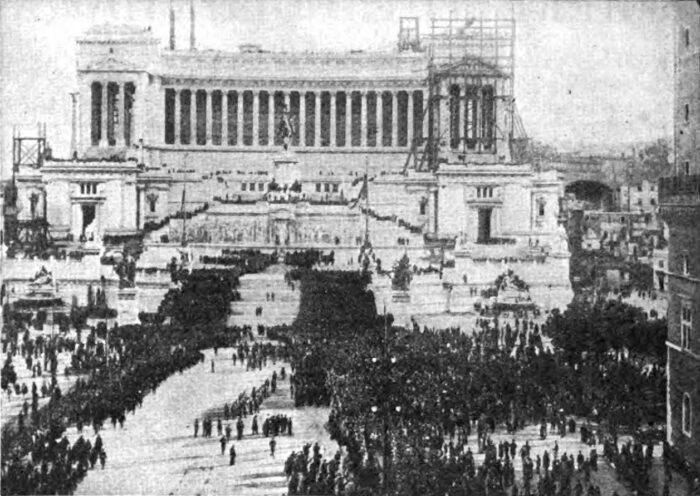

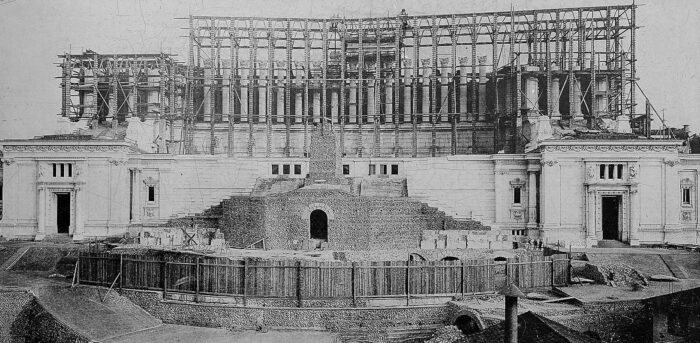

Like other tourists I viewed Vittoriano without understanding it, and when I asked my Roman friends I found they took little interest. They mocked its ostentatious style, they gave it confusing names. It took time for me to realise that its history contains a national drama, and stored inside were exhibitions that documented national history and state power. The monument in Piazza Venezia is a work in progress, a shadow to the young nation it glorifies. Construction started in the 1880s to commemorate the first king of a unified state, Vittorio Emanuele II. The monument was incomplete when inaugurated in 1911 to mark the 50th anniversary of a unified nation. After Italy’s territory expanded at the cost of 651,000 Italian lives, it received the remains of an unknown Italian soldier in 1921, killed in action during the First World War. Ever since, The Unknown Soldier has been treated by some as a uniquely patriotic place, a symbol of national reflection and mourning.

The following year, 1922, during the March on Rome, Mussolini’s Blackshirts gathered on its steps and two catastrophic decades of Fascist dictatorship began. By the time it was complete in 1935, Vittoriano was no longer a monument to a dead king, or not only this. It also became a place of national reinvention and revolution, and it was given a new name that rhymed with the era’s ultranationalist spirit, Altare della Patria (‘The Altar to the Fatherland”). In the post-war Republican era, Vittoriano has had its uses adapted and expanded, while retaining a quasi-religious status—one that platforms a unique patriotic reverence and gives glory to national memory and honour to patriotic blood sacrifices.

Now Italy is ruled by a right-wing coalition, who came to power championing a nationalist policy agenda, Vittoriano’s significance has altered, again. This is partly due to how nationalism is used by the current government. When forming her party in 2012, Giorgia Meloni said Fratelli d’Italia were “the abandoned children” of a neo-fascist tradition, Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI)—a party established in 1946 to hold the flame for Mussolini’s defeated Fascist Party. In the lead up to the 2022 elections, Fratelli d’Italia promised to defend Italian families and religion, halt the ethnic replacement and “mass extinction” of Italians, reverse uncontrolled mass immigration, and reject what it calls “cultural Marxism” and the “LGBT dictatorship.” [1] The US political strategist Steve Bannon recommended Donald Trump to “Flood the Zone” and confuse opposition in the media, while Meloni has a zone already flooded with political relics and cultural war phantoms, used by a loyal group of allies to belittle “poor Communists” should they ever raise their voices. Meloni has reanimated the “patriotic soul” of conservative nationalism, one that assumes an independent, anti-globalist and anti-immigrant cause, and which uses history strategically to threaten Italians and make Fratelli d’Italia a party of safety and security. After all, “we did not fight against, and defeat, communism,” she said, “in order to replace it with a new internationalist regime.” [2]

In the short years since Fratelli d’Italia came to power, small changes to Vittoriano have been observed. On 25 October 2025, for example, Vittoriano opened a new exhibit, Mostra degli Esuli Fiumani, Dalmati e Istriani (MEDIF) in the Sale del Grottone , a space deep inside the monument. The exhibit (curated by Massimilliano Tita, 24th October 2025–25th October 2030), open for the next five years, remembers the Italians murdered or exiled from Fiume, Dalmatia and Istria, as many as 350,000 displaced, according to this exhibition. [3] The foibe massacres were reprisal killings that followed Italian armistice in 1943 and the retreat of Axis forces in 1945, events that remain pivotal to how Italians remember the horrors of Communism and memorialise the tragedy of war. The commemoration of foibe killings are pivotal to how far-right and neo-fascist activists want Italians to remember the Second World War, one that centres Italian victimhood and the perils of failing to protect citizens from Communist murderers.

Inside the Sale del Grottone, a broadly chronological narrative is recounted on touch screens. Here we read that Italian people have inhabited the regions of Fiume, Dalmatia and Istria since the first Imperial Roman settlements were established there 2000 years ago, and Italians inhabited the region in 1915, when Italy entered the First World War against the Austro-Hungarians. We follow the sabre-rattling that brought Italy into the War, as if there was no challenge to or debate about territorial expansion. Neither is there space for critical reflection on national, ethnic or racial categories of identity and belonging. We learn that redeemed areas that were incorporated into the Italian state after the First World War underwent aggressive Italianisation, and this enhanced the “Italian” status of their population. If a region can become more or less Italian based on government policy, then what of Gabriele D’Annunzio’s “cause of the soil” and the occupation of Fiume? The touch screen texts and labels are only available in Italian. They do not mention D’Annunzio.

Other techniques of storytelling play an important role in shaping the kind of history these touch screens tell. The events of the 1920s and 1930s are not displayed unless actively selected by visitors. The texts, if chosen, hint at episodes of Italian violence, civilian persecution and the execution of dissenters. Just one screen describes the single biggest contextual factor for the foibe killings—the Italian invasion of the region as part of the Second World War. Popular and scholarly research testifies to the scale and severity of Italian violence against Slav and Croat peoples: ethnic cleansing; massacres against Partisans and civilians; the mass internment in concentration camps whose death rates were greater than Buchenwald. General Roatta called for “ethnic clearance.” [4] This is an exhibition that gives a limited moral compass to visitors, since it passes no judgement on the Italian Fascist regime or its violent ethnonationalism, it acknowledges no consequence for Italian brutality and ethnic cleansing, or participation in the Holocaust. The exhibition focuses on Partisan actions against Italians in 1943 and 1945 as an uncomplicated tragedy for present-day Italians. We are invited to follow the Unknown Soldier into apolitical mourning, a vacuum-packed space reserved for history’s victims. The right to “full scale invasion”—to use the language of contemporary geopolitics—precedes the right to occupy and punish civilians, the right to ethnic cleansing and genocide for the sake of national glory. If this exhibition flatters Italians as history’s good guys (“brava gente”), a moral army, it goes further by suggesting that it has been unfairly or unjustly treated (povera gente). This is a simplistic memory trick also favoured by neofascist groups like CasaPound, who march on the streets of Rome each year to claim foibe victims as martyrs in support of a special brand of white nationalism. For groups like CasaPound, the memory culture of the foibe is a martyr culture that shapes militant futures. The spirit of Italian ethnonationalism is kept aflame, its parts in tricolour.

Such a pattern of bias would need to be seen elsewhere at Vittoriano to rise above the level of error or conspiracy. And so visitors are able to exit Sala Grottone and visit Sala Zanardelli on the next floor—the temporary exhibition space. One current exhibition, Le ferrovie d’Italia (1861–2025): Dall’unità nazionale alle sfide del futuro (curated by Edith Gabrielli, 7th November 2025–28th February 2026), marks 120 years since the formation of the state railway. It spreads across two, long, barrel vaulted galleries, as if the exhibition itself is travelling along Italy’s rail network, while another room provides an immersive, multi-screen railway experience. The exhibition is composed of artefacts and photographs, sculpture, paintings and commercial media, becoming two different kinds of exhibition at once—a conceptual and interdisciplinary record of artistic responses to rail travel, and a national and cultural chronicle where railways serve as a leitmotif or object-study in a wider social history. The show is both dirrestissma and regionale for being bifocal, providing a rapid and landscape view of Italian experiences of railway development, while lingering on stop-motion experiences of complex, 20th century ideas such as the artist response to technology, modernity and speed that defined generations of Italian artists and artistic movements.

The exhibition stops briefly at “Fascism” to describe the most dramatic transformation of the exhibition’s dual protagonists—rail and state. At a juncture when norms of the Liberal state were torn apart, the exhibition highlights technological innovations and labels these “modernity” and “progress”. A combination of passive-voice narration and uncertainty about who or what defined progress, or what constitutes “modernity”, results in another unclear presentation of what the curators are saying about the past. Visitors are told rail “became the lynchpin of economic policy and collective imagination” for the Fascist regime while for artists in this era, “the train continued to embody the ambivalence of modernity.” Ironically, we have to guess at what ambivalence means here. We know “modernity” and the train network were controlled by the Fascist state, speeding towards destruction. And propagandists put Mussolini at the controls of electric trains that broke land speed records. The major developments of state centralisation and electrification were not only technical but achieved thanks to ending democracy in Italy. The costs of Fascism and the Fascist control should not be erased, nor do they deserve ambiguity.

Ambiguity creates confusion about the Italian state, and a reluctance to examine how nations like Italy were formed, collapsed and were remade. In these exhibitions the Italian people belong to an idealised land, where citizenship is universal and continuous rather than a legal status, fought for and contested over time. Despite rail being a lynchpin to the history of Italian colonisation, Italian colonies and colonial subjects do not feature in this exhibition. But while colonies come and go and wars tear at democratic norms, the failure to think clearly about the state means the artists presented in Le ferrovie d’Italia also struggle for political context and agency. Artworks by Mario Sironi, Fortunato Depero or Angiolo Mazzoni, for example, are uncritically celebrated in this exhibition for their canonical and technical status, as if each artist worked for the patriotic love of Italy and rail travel. As artists and in different ways as individuals they were loyal to Fascism and to the party, paid and promoted by the regime, and would not feature in this exhibition were it not for their party loyalty.

Turning a blind eye to the ugly and unresolved past is a feature and not a bug of nationalist populism, often fearful of uncomfortable truths. It would prefer to airbrush the history of totalitarianism with some upbeat and defiant patriotism. This nationalism is not unique to Italy, of course, and can be found anywhere nation states are treated as a natural and inalienable good. The trouble is that the idea of naturalness soon passes and emboldens a wartime sentiment and the unevenly recognised right to defence used to justify conflicts around the world. Populism may be defensive, evasive or even embarrassed for a time, before it enters into a national conservative phase now favoured by some current world leaders. This is the politics of provocation and insult, the autocratic and emotive group formation that constantly needs to threaten people with expulsion—immigrants not welcome, protest not welcome. Italia agli Italiani. It wants no critical life and, at its most extreme, it will silence even its weakest critics. Fear and self-censorship are signs that citizens of this system anticipate expulsion if they do wrong. And only a self-censoring exhibition about the state’s railways could fail to mention the railway station bombing of Bologna in August 1980. Every Italian learns about its horror, where 73 were killed and 291 injured. The terror attack on Bologna is remembered as a definitive event in the history of the Italian Republic, one awful crescendo in a civil war between armed groups and the Italian state, Italian extremists and Italian agents of the state who promoted terror against their own. Neofascist terror and state terror are hard to memorialise within a patriotic Italian ideology championed by the current government, who want you to fear everything and everyone but them, Fratelli d’Italia. Wherever there is a demand for a homogenous “national consciousness” of custom, language or tradition, wherever we demand that people “integrate” to safeguard their survival, we must recognise the twentieth-century’s most enduring and dangerous fantasies. Meanwhile these exhibitions give a place, deep inside a monument to vain-glorious losses, to think critically about the nation as fragile and fallible, an invention of a very particular history.

[1] For an analysis of Fratelli d’Italia’s manifesto Trieste Theses and its relationship to Italian nationalism, see David Broder, Mussolini’s Grandchildren: Fascism in Contemporary Italy (London: Pluto Press, 2023), pp. 17–46.

[2] Giorgia Meloni, “National Convention in 2020”, YouTube Feb 22. Cited in Broder, Mussolini’s Grandchildren, p. 55.

[3] Figures are disputed and it is significant that MEDIF uses an upper estimate, c.f. Raoul Pupo and Roberto Spazzali, Foibe (Milano: Mondadori Bruno, 2003), where they estimate a quarter of a million people affected.

[4] See Davide Rodogno, Fascism’s European Empire: Italian Occupation During the Second World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 148, p. 335.