Make Anguane Frightening Again

On Chiara Cecconello’s “Aganis”

Since childhood, the word Anguana has resonated with me as something suspended between memory and folklore. It brings me back to my grandmother’s house, the only one standing on the edge of a small clearing near Lusiana, in the uplands of the Sette Comuni (Vicenza, Italy). Near the house there was a rock wall with hollows, almost like small caves, which were described as gathering places for these creatures. Among them, a wide rocky spur with a hollowed-out core forming a long, deep cavern was renamed sojo delle streghe, the witches’ ledge. According to legend, it was there that the anguane would meet at night to perform their rites, leaving behind blackened traces of soot on the rock walls as evidence of their passage. The image I built as a child, through my grandmother’s stories, was that of malevolent female figures, appearing as old women emerging from the forest to assemble in strange nocturnal gatherings where they performed mysterious rituals.

Only later did I learn that, in those same places, the symbolic presence of the anguane was tied to an important social function. The caves, in fact, truly hosted nocturnal gatherings. Yet these were not the creatures of legend, but local groups who, far from police surveillance and in the midst of an economic downturn, would meet in secret to exchange and share contraband stuff: tobacco, foods, but also pistols and rifles. The fires they lit bore a double semiotic functions: they announced that trade was taking place and that no state officials prowled the place below, while at the same time they warded off the curious, especially children, by feeding them tales of fearsome beings and their sinister assemblies. The association between witches and the creation of temporary free zones recurs frequently in the analysis of anguane. Luisa Muraro, for instance, in her study of the witch trials of the Val di Fiemme, shows that behind the nocturnal gatherings led by the dona del bon zogo lay preparations for peasant revolts.

It is difficult to give a precise definition of what anguane are. Like many other non-human beings embedded in the oral traditions of the Venetian Prealps, they are described in fragmentary and often contradictory ways, shifting from village to village. What remains constant is their monstrous aura, carrying with them something untamed and feral, tied to caves, swamps, and wooded places. In some stories they resemble sirens or nymphs—the word anguana itself derives from the Latin aqua—while in others they appear as women marked by animal traits, such as goat-like feet.

Unlike witches, with whom they share affinities with bestiality, anguane are also connected to more ambivalent or even beneficial aspects: the use of goat’s milk is said to come from their teaching, as well as the gift of foretelling the future. In one of the earliest mythological accounts of the Dolomites, The Kingdom of the Fanes—collected and reconstructed by Austrian anthropologist Karl Felix Wolff in 1932—the anguana is described as a «woman of the waters», warning the hero Ey de Net of impending dangers. Yet more often than not, popular tales emphasize their malice, linking them to disappearance, sickness, and death. A saying still common in the area around Vicenza goes, unsurprisingly, l’è ciucà da le strìe (“he’s drunk from the witches”). It’s used to describe a man returning pale and exhausted from work in the forest or on the mountain pastures, after allegedly encountering the anguane. Survival itself was already a form of grace: the anguana did not merely seize men for fleeting encounters, but could drain them to the point of death, or tear their bodies apart.

In their most menacing aspects, the anguane reverberate with the dynamics Silvia Federici traces between the birth of capitalism and the war against women. The same historical process that outlawed prostitution in Europe, confined women’s activity to the domestic sphere, and crystallized the figure of the housewife, also expelled female subjectivities from waged labor. Against this backdrop, the anguane—stealing men from both their toil and their matrimonial bonds—appear as a feral monster haunting the very core of the family. Dwelling in the forest, beyond the reach of the social contract, they embody its rupture, its fragility. Men, sole bearers of labor-power, cease to produce value. After these encounters that carry them into a dimension not fully reducible to the human, they literally stop functioning.

Yet anguane can also, at times, be drawn back into a framework of patriarchal domestication and neutralization. In tales that recall the more famous story of Melusine, they become—at least temporarily—human wives and impeccable mothers. Melusine is an inhuman being who consents to marry a knight, Raymond, on the condition that he leave her undisturbed on Saturdays. Yet the birth of children with animal features compels Raymond to break the pact, discovering that his wife’s lower body is not human but, depending on the version, that of a serpent or a fish. In some variants, Melusine secretly returns in serpentine form to care for her children. Likewise, Venetian traditional tales speak of men enchanted by a young woman’s beauty, never suspecting that she is an anguana. She consents to marry him, yet only on a condition that—though it shifts from tale to tale—always comes down to forbidding an act that would expose her true identity.The tale invariably ends in failure: the man violates the agreement, and the outcome is nearly always tragic. The relationship between humans and anguane deteriorates precisely when a physical detail, most often the goat-like feet, is revealed, reminding the anguana of her radical difference in nature and forcing her to abandon the precarious security of human society, often to declare war against it. Erasing their animal traits thus becomes the necessary precondition for their entry into the anthropomorphic world. The connection with Melusine grows even stronger when we recall that the etymology of anguana derives from the Latin anguis a root still preserved in the Italian anguilla. This in turn links the anguane to another well-known mythological figure: the siren. As «freshwater sirens», anguane embody all the negative stereotypes associated with their more famous counterparts. Like the sirens, they are accused of beguiling and abducting reckless men, serving as living tests of the masculine ideal of reason’s triumph over baser instincts.

It is no accident that the fragile covenant between human and anguana unravels at the instant a mark is revealed betraying the secret of her irreducible difference. In that moment of exposure, she abandons the precarious shelter of human civilization and turns against it, carrying her otherness like a wound that refuses to close. To erase the animal trace is the price demanded for entry into the anthropomorphic order. Yet it is precisely in rejecting such erasure that the anguana persists as a troubling remainder, unassimilable to any role deemed safe, innocent, or domestic. Bearing their hybrid essence with defiance, the anguane linger at the edges of society, ever ready to transgress, to reappear parasitically in fragments of story whispered from one generation to the next.

It is this very residue, this monstrous vibration, that forms the core of Aganis, the immersive quadriphonic performance with two voices by Chiara Cecconello. Having acoustically mapped the caves and recesses where local memory places these beings, Cecconello weaves the soundscape into a choreography that binds the wet cavern of the mouth to the hollow of stone. The mouth, like a cavern, is a damp cavity, thick with stagnant waters, from which sound breaks forth like an epiphany. Here the uncanny and the archaic are rekindled in echo: reverberations that return not as repetition but as excess, as doubling. Each vibration unsettles the borders of voice and matter, opening a passage where language collapses into resonance. In this trembling interval, the human ear is estranged from itself, caught in the murmurs of entities that speak without words. As François Bonnet writes in The Order of Sounds: A Sonorous Archipelago, “the echo, produced by the repercussions of a multiplied sound, plays a part in establishing a supernatural sonorous environment, ultimately providing alterity where there is only identity. The echo affirms the presence of a sound by revealing the milieu within which it is deployed, as the points from which it is reflected delimit its zone of influence.”

In Aganis, the performers’ call and response—sometimes layered, sometimes dissonant—traces its way back to the phantasmatic roots of sound. The mouth becomes the chamber where the scattered remnants of the anguane are gathered and reassembled, giving them acoustic body.

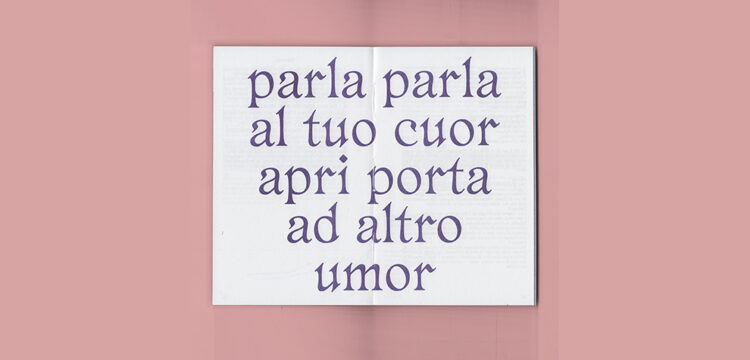

Their return comes as noise: shrieks, howls, cracked syllables that perforate the fragile membrane of human quietude. It is for this reason that the saying no stà sigàr come n’anguana! (“don’t scream like an anguana!”) was born. As Cecconello writes, the nonaudible is always that which must be regulated, that which must comply with norms. Neither fully human, nor wholly animal, nor purely monstrous, their cries carve out an acoustic space where taxonomies falter and collapse.

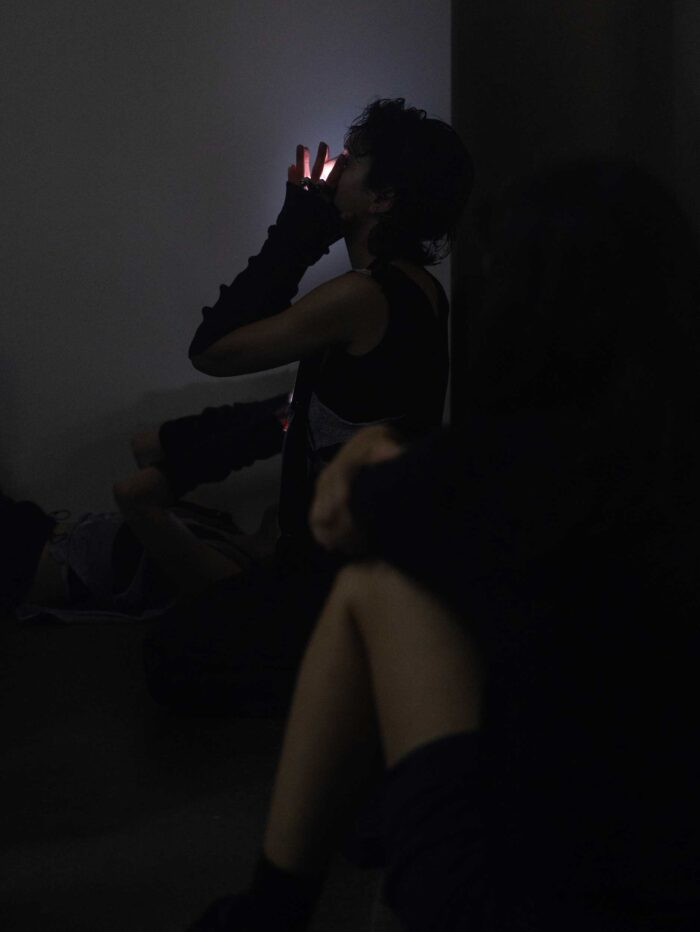

The performance space itself enacts this disturbance: plunged into darkness, vision falters, and the audience is compelled to listen with sharpened intensity. Eyes wander in vain, searching for the anguana’s cry. Meanwhile the performers drag themselves across the stage, leaving only spectral traces—whispered words, half-breathed phrases, chants breaking through the gaps between silences—as the sole guides through the sonic terrain. The flicker of these acousmatic presences, appearing and vanishing, points toward the slippery nature of the anguane.

Following Bonnet, we can recognize in Aganis an interpretation of sound that engages with three qualities pressing against the thresholds of human audibility: the informe, the imperceptible and the indeterminate. Drawing on Bataille and Didi-Huberman, Bonnet reminds us that the informe does not mean formlessness in the sense of absence, but rather dissolution. Is the undoing, the unravelling, the melting away of form. It is slippery precisely because it names not a fixed condition but a process, forces pressing, colliding, and eroding the boundaries of any given shape. In Cecconello’s work the voice drifts without pause from the cadence of song to the raw grain of bioacoustic fragments, to shrieks and piercing noise. It becomes a body in ceaseless disintegration. Never purely without form, yet never locked into a single form, it hovers in the fragile space between, oscillating, trembling, refusing to solidify into something stable or enduring.

These movements are not external impositions but arise from the very subjectivity that the sonic informe calls into being: the anguane’s decentered, elusive, and almost imperceptible presence.

Listening, then, becomes an act of waiting, of suspension. Listening is an anticipation of the next sound, uncertain whether the performers’ song will carry on or splinter into a shrill noise. The acoustic field of Aganis becomes a terrain of verification, a fragile check that sound has not been interrupted, that noise has not been extinguished.

In this way, the work conjures the echo of caves, where the anguane’s legends still reverberate and leave traces of their passage. In those subterranean spaces, as here, listening must adapt to a decentered subject: to a source that drifts in space, that shifts in intensity with time, that transforms its contours and gives rise to ambiguous presences, a phantoms that play with the echoes sculpted by the landscape itself.

Between the informe and the imperceptible there emerges a third movement, one that hovers and drifts between them: the indeterminate. This, too, should not be cast in a negative light, as if it were merely that which escapes precise or stable description. Instead, as Bonnet insists, it is what unsettles the ear, creating shifting points of attention, a temporary remodulation of the sensorium. It allows fragments of noise to surface in their rawness, to be apprehended before they are drawn into the taxonomy of already known and domesticated sounds. By chasing this phenomenology of sound forms, intertwining, colliding, and mutating into new configurations, and by decentering one’s own listening to move along the very threshold of the audible, the indeterminate comes to reveal itself as a space of listening. It is, in other words, the sonorous locus where the imperceptible and the informe continue to weave and counter-weave their effects.

To pursue the presence of the anguane—whether in the folds of oral tradition or the stony hollows of their former dwellings—demands not sight but a deepened hearing, a materialist acoustics that leads back to the watery and forested ecologies where these stories were first born. If in folk belief magic emerges at liminal thresholds—moments of passage where a being reveals two natures at once—then in Aganis it is the mouth that becomes the chamber of invocation. From its depths, the formless and imperceptible presence of the anguane is summoned anew through sound. As voice thickens into body, they return to creep through the forests, reclaiming with pride their hybrid nature and haunting oral culture with renewed insistence.