Jatiwangi Bodybuilding Cup

An annual competition for workers in roof tile factories in the Jatiwangi region in Java, Indonesia

Unorganised Response explores the ways in which artistic production is used as a tool for influence by organizations engaged in international cultural relations and diplomacy. Bringing together artists, activists and community organizers, this project asks how creative workers navigate local and international cultural infrastructures when commissioned to build connections, engender trust, and respond to complex geopolitical events. The project launches with an exhibition at Auto Italia featuring works from Kareem Lotfy, Christelle Oyiri and Grace Samboh + Julian Abraham “Togar”. The exhibition explores the ways in which artists mobilize critically and collectively to resist being reduced to their various identity markers, through a series of projects that explore advocacy and self-organization through personal and often celebratory experiences. Here an excerpt from the publication accompanying the exhibition, Auto Italia in conversation with artists Julian Abraham “Togar” and Grace Samboh.

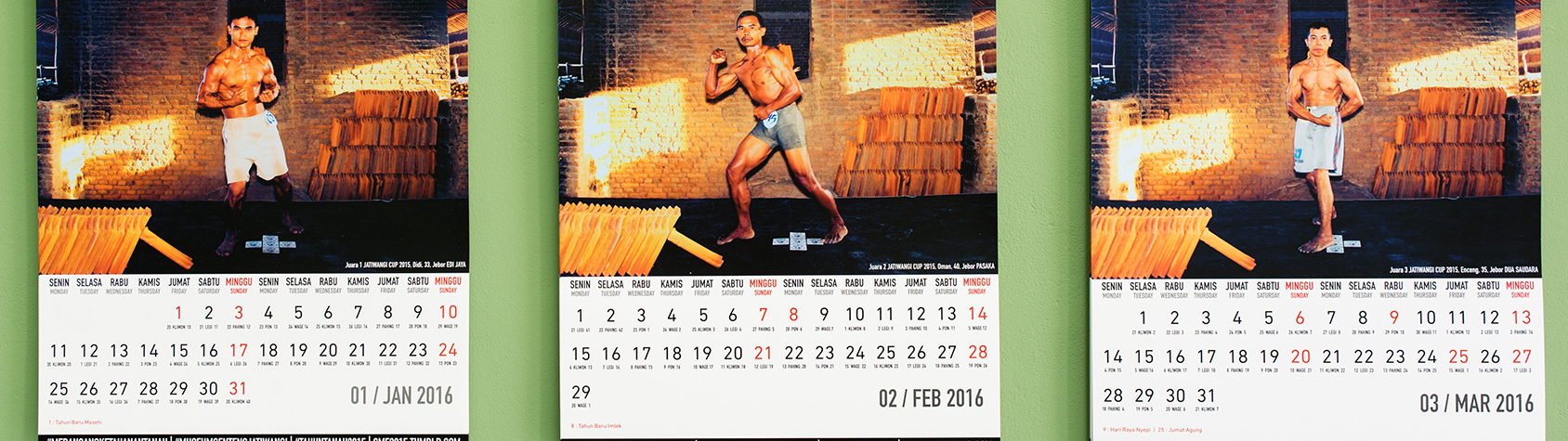

Auto Italia: Grace and Togar, in the exhibition at Auto Italia you have presented a series of calendars that were produced as part of the Jatiwangi Cup in 2015. Could you start with a brief description of the Jatiwangi Cup and tell us more about its background and how it began?

Grace Samboh: Jatiwangi Cup is an annual bodybuilding competition for workers in roof tile factories in the Jatiwangi region in Java, Indonesia. It was initiated in 2015, when myself and Togar were living and working in Jatiwangi for a year. We wanted to experiment with whether we could—as art workers—live and work in a different context to culture centres in Indonesia such as Jakarta and Yogyakarta. During this time, we began discussing the idea of a bodybuilding competition with Jatiwangi art Factory (JaF), Illa Syukrillah Syarif (Jatiwangi Roof Tile Museum), and factory owners who were interested in supporting the project.

Participation in the competition is only open to roof tile factory workers who have built muscles and strength as a result of the physically strenuous labour of producing roof tiles, or, in other words, those who have “embodied the earth”. The Cup’s prize is 10,000,000 IDR, which is six times the average monthly wage for labourers in Jatiwangi and the whole Majalengka Regency. Several factory owners we were hanging out with helped convince other owners to send their employees to join and offered to pay a 100,000 IDR registration fee for each employee.

The Cup has always been held on 11 August. This date marks the beginning of the annual Indonesian Independence Day celebrations. We intentionally scheduled the Cup to be part of these festivities so that the contest was quickly accepted and embraced by the local community much like other competition-based events staged as part of the national celebrations.

Julian Abraham “Togar” and Grace Samboh, Jatiwangi Cup Calendar, 2015. Courtesy Auto Italia. Photo Lucy Parakhina.

AI: The Jatiwangi Cup appears to have grown significantly in reach and scale since its first iteration. What has its trajectory been since it began in 2015?

Julian Abraham Togar: Everybody wanted something different from the Jatiwangi Cup when it first started. Grace and I were exploring it as a format that could bring people together and also enable us to create new work, for example through an annual calendar of the contestants. The Jatiwangi Roof Tile Museum had an interest in reminding people of the important cultural and economic purposes of the tile-making industry in the region, JaF had a focus on projects exploring mud, clay and earth, and the participating factories had a nostalgic yearning for a time when factories were a place for socialising as well as work. For those competing and attending, it was another celebratory event as part of the independence day festivities. When putting together the first iteration of the Jatiwangi Cup, we did not predict that competitors would become local heroes and idols, and that a number of national television channels would cover the event every year.

The Cup will have its fifth iteration in 2019. When the project began we never imagined that it would continue for so long. After announcing the winners of the Cup in 2015, Edi Malik Azis, the owner of the roof tile factory where the inaugural winner worked, announced that his factory PG Edy Jaya would host the Cup the following year. The Cup has continued this tradition and is hosted at the factory worked in by the previous year’s winner.

Christelle Oyiri, Collective Amnesia (Call and Response), 2019. Courtesy Auto Italia. Photo Lucy Parakhina.

Christelle Oyiri, Collective Amnesia (Call and Response), 2019. Courtesy Auto Italia. Photo Lucy Parakhina.

AI: In a piece of writing on the very first Jatiwangi Cup, you stated that “since the tax-free agreements between ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) members in 2007, multinational garment factories have begun to appear in Jatiwangi. The tile factories have lost their appeal to workers”. Could you expand a little on this and the position that the tile factories in Jatiwangi hold in the region in relation to this expansion of the garment industry?

GS: In 2014, ASEAN was the third largest market in Asia, and the seventh largest in the world. Indonesia is the largest country in ASEAN, by population, by density, and by geography (be it land or ocean). When we first visited Jatiwangi in 2014, we were witnessing the large scale changes in people’s livelihoods across the region. Villages were being relocated for what we now know as the Trans-Java Highway. Roof tile factories were closing down and selling their lands to what seemed to be engineering or garment factories, and the new Kertajati International Airport was being constructed—the second largest in Java.

Java is the smallest of the five largest inhabited islands in Indonesia’s archipelago. However 60% of Indonesia’s population lives in Java to be closer to the capital city, Jakarta, which is only 180 km away from Jatiwangi. The then-Regent of Majalengka Regency—the leader of an inherited political dynasty in which Jatiwangi sits—disliked the roof tile industry that has existed here for at least a century. He wanted to convert his Regency into a modern, industrial area, and his understanding of industry was limited to the big multinational textile companies that need large empty grounds on which to build their factories. The Jatiwangi district is perfect because of how it is situated within Java: the landscape is relatively flat, the inter-province main road crosses right through the middle of it, and it is near the two big trading ports of Cirebon (West Java) and Tanjung Priok (Jakarta).

Indonesia’s President, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (2007-14), proposed the idea of an ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) at one of the ASEAN’s regular meetings in Singapore. Before AEC had even launched, several countries—including Korea, Japan, China—had begun attempts to access land in Jatiwangi. Majalengka Regency’s desire to convert into an industrial area was therefore relatively simple to enact: by facilitating a number of multinational companies searching for land to build mostly engineering and garment factories. Land prices are also much lower in comparison to Jakarta’s suburban areas, which were industrialized even before independence. In addition, Majalengka Regency’s regulation of wages and workers’ rights are far more loose, so it is still possible for these companies to hire workers on limited contracts and avoid paying workers health insurance costs that they would be required to pay in other parts of Indonesia.

Unorganised Response Reader, Authors various, edited by Auto Italia, 2019. Courtesy Auto Italia. Photo Lucy Parakhina.

AI: You mentioned earlier that the Jatiwangi Cup has been a nationally televised event since the first iteration. Quick searches on Google also draw thousands of image and video results. Could you talk a little more about how it has felt to see the project become so popular. Has it affected the way the project is read and understood?

JAT: The media spectacle that has been created by the Jatiwangi Cup has enabled communities living and working in the region regain confidence that their traditional industries are something to be proud of. This is an important goal of the project, as so many people in the region have been moving to major cities in search of new forms of work. This takes us to one of JaF’s aims, as Director Arief Yudi Rahman says: “Usually, people need to go abroad in order to be able to appreciate what they have back home. Before we can afford to send everyone out, let’s borrow the eyes of these outsiders. Hopefully, by socializing with other citizens of the world, people in Jatiwangi appreciate the good side of their livelihood.” This is achieved by supporting villagers to host JaF’s guests in their houses, be it art workers in residence or audiences coming through town to witness cultural life in Jatiwangi.

In doing so, the aim is to refocus attention on ideas of the self / community / village. Whether this strategy has worked on a long-term basis is of course another conversation, however in the Jatiwangi Cup’s case it feels like our work to create something the villages are proud of—very much within the context of JaF’s long-term work in this area—has been a success. The Cup is now self-managed by the factories and continues to drive high levels of local tourism to the region. This may not be the only solution for keeping the history of traditional roof tile factories going but we hope that it could be a start of the discussion. The Cup has given us, as art workers, the chance to be a part of building a new tradition.

Unorganised Response, Installation view at Auto Italia, 2019. Courtesy Auto Italia. Photo Lucy Parakhina.

AI: How do you see your role as artists within this project as it has grown over the years? We sense a real slipperiness in the work between having aims as both a community initiative and an evolving live artwork. Do you feel a sense of duty or even a certain subterfuge afforded by the title “artist” when working this way?

GS: Stories about the Jatiwangi Cup are never intentionally told in a way that aims to frame it as either an art project or a community work. When Togar and I speak about the Cup, these conversations of course happen because I am a curator and Togar is an artist, however we do not feel that everything we do needs to be immediately be claimed as art or a creative project. The Cup is for everybody to own. Anyone who is interested can own the Cup in their own way. Yes, indeed, we were part of making the first one but it was never only ours. So when we discuss it now, we approach it as people sharing our excitement, fascination and questions that the Cup raises.

Exhibiting elements of the Jatiwangi Cup has always been driven by conversations with exhibition-makers and aims to be an announcement of the Cup as a form of solidarity towards other non-object-making driven practices that are exhibited alongside it. We feel that there is a necessity to spread the word that this modality of practice exists. As instigators of the Cup, we had initially not considered how the project might be read for audiences encountering the project for the first time. Now approaching the fifth edition of the Cup in 2019, we are interested in exploring the position of the audience through our work. To a certain extent, this is because organization of the Cup can happen on autopilot as a regularly occurring and living ritual, a tradition managed by its locality. We want to be the people who come to the Cup to watch, to be entertained, and to come home with stories. We want to experiment in taking something different out of the Cup ourselves, out of Jatiwangi, out of its location, out of its activation.