Intelligence beyond the Boundaries of the Individual

A conversation with Nicolás Lamas

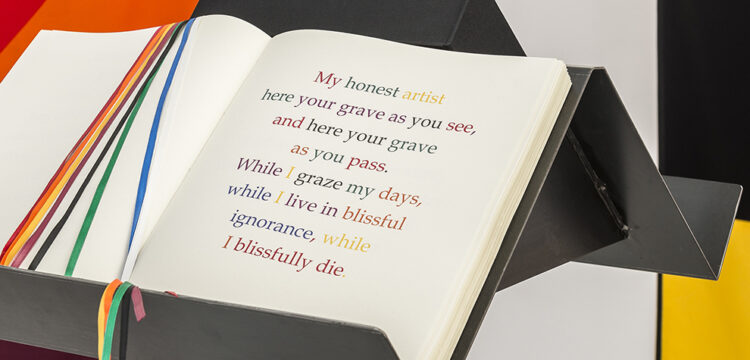

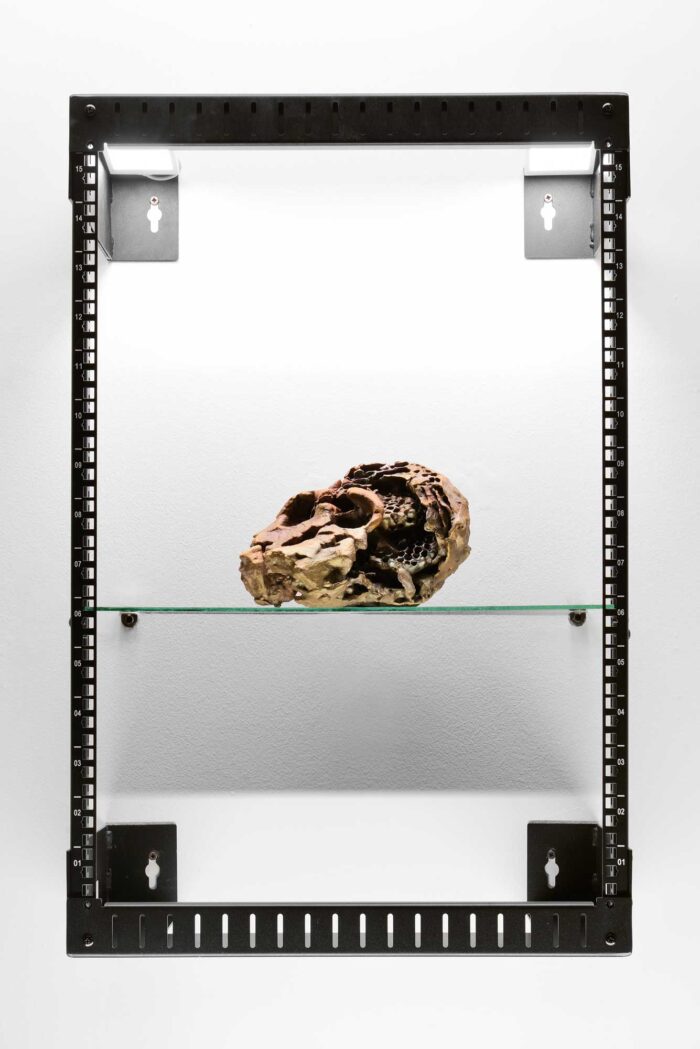

Collective Memory is an installation project born at the intersection of archaeology and the digital condition. Within a structure resembling a server—a symbol of contemporary data flows and invisible infrastructures—a bronze cast of a Kenyanthropus platyops skull and a wasp’s nest, a fragile trace of non-human collective intelligence, are fused together. In this hybrid form, different scales of time and modes of cognition collide: the “solid brain” as the stable architecture of living beings, and the “liquid brain” as the distributed, decentralised logic of insects and artificial systems. Nicolás Lamas’s work exists within this interval between the organic and the synthetic, the ancient and the digital, the individual and the collective. His installation transforms everyday fragments and historical artifacts into carriers of new meanings. Like an archaeologist of an imagined time, the artist investigates how memory, agency, and the very form of matter are reconfigured in the age of networked structures, inviting us to consider intelligence as a process that emerges within constantly evolving systems, biological and technological alike. This presentation of Collective Memory takes place as part of the fourth chapter of OVERTON WINDOW, a street-facing vitrine project presented by Matèria and curated by Re:humanism, which explores the intersection of art, technology, and contemporary digital culture. The series provides a context for engaging with emerging forms of artistic production and the evolving relationships between creative practice and digital infrastructures; it is within this framework that our conversation with Nicolás Lamas unfolds, offering insight into his approach, conceptual interests, and the questions that guide his work.

Asiia Gabdullina: With the development of technology, new terms have emerged that help us understand and interact with it. For example, within the concept of collective intelligence, some authors see the swarm as an effective model: flexible, resilient, self-organizing, and capable of reflecting the complexity of the world; others interpret the swarm effect within theories of collective intelligence as the incorporation of automatisms into our nervous and social systems; and some warn about the danger of a “hive mind,” speaking about the risk of zombification. How did the image of the hive come to you?

Nicolás Lamas: My interest in the hive or the swarm did not arise directly from a conscious interest in biology, but rather from observing the interactions between bodies in motion. I remember that a few years ago, I became interested in billiards as a closed system where forces, trajectories, and collisions produce infinite combinations and interactions, all governed by specific laws and rules. Later, this interest shifted toward other team sports, where bodies compete, collide, and constantly reorganize within a given space, generating collective dynamics that cannot be reduced to individual will, which gradually served as a metaphor for reflecting on the emergence, development, and collapse of societies.

This shift progressively led me to think not only about human bodies but also about objects, commodities, data, and other non-human systems, all functioning as agents within constantly moving systems. At this point, the image of the swarm or the hive appears almost naturally as a model to understand how certain forms of organization and complex patterns emerge from very simple interactions between individuals within a collective, without a clear center of control, but rather as a collective force or a super-organism.

In your work, you use a bronze cast of the Kenyanthropus platyops skull. This is an intriguing fragment of anthropological history, since Kenyanthropus platyops is still one of the most debated among the proposed human ancestors. Because of the condition of the fossil, even evolutionary scientists cannot agree on its place in human history. Moreover, palaeontologists point to its flat face and to its comparatively small brain. What exactly drew your attention to Kenyanthropus platyops?

What attracted me to Kenyanthropus platyops was its fragmentary condition and the intense debate surrounding its place in hominid evolution. The fossil was discovered in hundreds of incomplete fragments, which has made its study extremely challenging. This tension between fragment and whole, between evidence and speculation, is profoundly fascinating to me: a puzzle in which incompleteness is not a flaw, but an open space to imagine, reflect, and revise our narratives. This skull thus becomes a testament to the uncertainty inherent in all knowledge, and to how our stories always contain gaps and contradictions that compel us to rethink them.

I am interested in thinking of the skull as the ruin of a container that once held cognitive activity, much like a wasp nest functions as the material echo of interactions within the hive. In this way, the skull and the nest enter into dialogue: both condense the relationship between fragment and whole, between individual and collective; they differ, yet also complement each other within a hybrid form that opens up a series of questions through its own ambiguity.

Let’s talk about the concept of the “liquid brain.” In Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris—adapted into the film by Andrei Tarkovsky—we encounter a sentient ocean; and Arthur C. Clarke created the Firstborn, pure consciousness/energy beyond a biological body. How does the notion of a “liquid brain” appear in your work?

The notion of the “liquid brain” interests me as a way of thinking about intelligence beyond the boundaries of the individual: not as something that resides exclusively in an organ or a body, but as a distributed phenomenon that emerges from connections, interactions, and flows between different units. It is a concept that appeals to me both for its poetic potency and for its capacity to translate into material forms: bodies, objects, technologies, and environments form a network in which cognitive processes are neither linear nor centralized, but adaptive and relational. This idea allows me to imagine the mind as something procedural, always in transit, shaped and reshaped by the connections that traverse it, and manifesting in forms that extend beyond the human, and even beyond the biological, reaching into data and technology.

In my practice, this notion translates into installations and objects where the organic and the technological coexist, blend, and contaminate each other, suggesting that processes of thought are not separate from their material substrates or the contexts in which they unfold. Intelligence, understood in this way, resembles a liquid: it flows, adapts, distributes, and leaves traces of its movement. Every interaction, every contact between materials, activates a complex network that is constantly expanding.

Your work suggests viewing collective experience not as something exclusive to humankind, but as a network of interactions between different forms of life and matter beyond a specific temporal frame. Does this mean that you construct interconnections between the individual and the network, nature and technology, past and present?

Yes, exactly. My work starts from the idea that collective experience is not exclusive to human beings, but emerges from networks of interaction that include organisms, materials, and processes that transcend any specific temporal framework. In this sense, I aim to articulate interconnections between the individual and the collective, between nature and technology, and between past and present. These networks are not hierarchical, but distributed and adaptive: patterns emerge from local interactions, and these emergent behaviors, in turn, shape the evolution of the network itself. By studying these interactions, we can understand how memory, information, and cooperation manifest beyond a single organism or a single historical moment, revealing the continuity of collective intelligence across multiple scales.

Your work often unfolds through an ever-changing archive of objects, ideas, and materials. How do memory and archival thinking intersect in your practice?

I do not work with archives as closed repositories of data or as static collections; for me, the archive is a living space, a terrain where objects, images, and materials layer, transform, and contaminate each other. Memory is not preserved as an immutable record, but is negotiated, eroded, recombined, and reinterpreted each time it comes into contact with new experiences or contexts. Each object, each fragment, can trigger unexpected associations, subtle tensions, or connections that were not anticipated. This dynamic makes the archive not a place of closure, but a device of openness, always in motion.

My archival logic resembles a rhizome more than a straight line: there is no clear beginning or end, only multiple branches extending in different directions. Each intervention, each reorganization of materials, becomes a space for active thought: a place where memory is not only remembered, but constantly rewritten; where objects and materials participate in the construction of meaning; and where the experience of the present dialogues with remnants of the past and speculative anticipations of possible futures.

Today, we live in a world shaped by artificial intelligence, where algorithms influence public opinion and filter information, determining forms of access to collective knowledge. How do you rethink the very concept of collective intelligence in this reality shaped by AI?

The presence of artificial intelligence is radically transforming not only our capacity to accumulate knowledge but also the way societies organize themselves and make decisions. However, AI does not replace collective intelligence, as it lacks true understanding, an evolutionary history spanning millions of years, and the plasticity that characterizes living systems. Algorithms can accelerate certain connections and reveal patterns that the human mind cannot perceive, but they do not substitute the shared experience, imagination, or creative capacity that societies have developed over the course of history.

Collective intelligence has never relied solely on technology; it is sustained by shared myths, cultural norms, and common narratives that allow millions of individuals to act as if they were part of the same project. Algorithms represent a new form of coordination: faster, more complex, and more efficient, but without deep comprehension, ethical awareness that emerges from human collaboration. True collective intelligence arises from conscious bonds, shared values, adaptive capacity, and the ability to imagine and create collectively—not just from filtered information. In this sense, AI functions as a powerful tool that reconfigures the flow of information, while authentic collective intelligence emerges from real interaction, meaningful communication, and adaptive responses to complex environments, as occurs in biological systems.