Imagination Machine

Sisterhood as a curatorial proposition and resistance tool within the sphere of labour, production and reproduction

The following essay is an excerpt from Joanna Sokołowska, Imagination Machine, first published in All Men Become Sisters, edited by Joanna Sokołowska (Berlin: Sternberg Press and Muzeum Sztuki, 2018), xx–xx. The book is both a record and a theoretical expansion of the exhibition All Men Become Sisters, held at the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź in 2015–2016. The exhibition and its accompanying performative program proposed a feminist appropriation of the idea of brotherhood, and negotiates and mediates social alliances through the concept of sisterhood—a category, which has the potential to transgress gender boundaries. The main battleground of this struggle is the sphere of labour and production, as well as reproduction of life.

From now on, everything’s going to change! These words, uttered by a little girl, announce the end of patriarchy and the becoming of sisterhood in one shot of Agnès Varda’s short film Women Reply: Our Bodies, Our Sex [Réponse de femmes: Notre corps, notre sexe], a feminist work produced in 1975 for the French public television channel Antenne 2. The reply was collectively formulated by a group of women who, taking as their point of departure a critique of the rampant sexism in the media, demanded the right to self-determination in all areas of life: from the rules governing the representation of their own bodies, through sexuality and reproduction, to education, labor, and love, and—by extension—demanded a total revolution in social relations. Referencing the subversive ambitions of second-wave feminism, the exhibition All Men Become Sisters offered a genealogy and manifestation of sisterhood in the medium of art from the late 1960s to the present day. Setting forth from its critique of the exploitation of women by patriarchy in both its capitalist and socialist forms, sisterhood poses questions about future social and economic relations, with a planetary ecology in mind. Sisterhood is a machine for working with the imagination; it spits on Hegel, dialectics, the belief in linear progress, brotherhood, the patriarchal culture of domination, and the struggle for recognition of mastery.

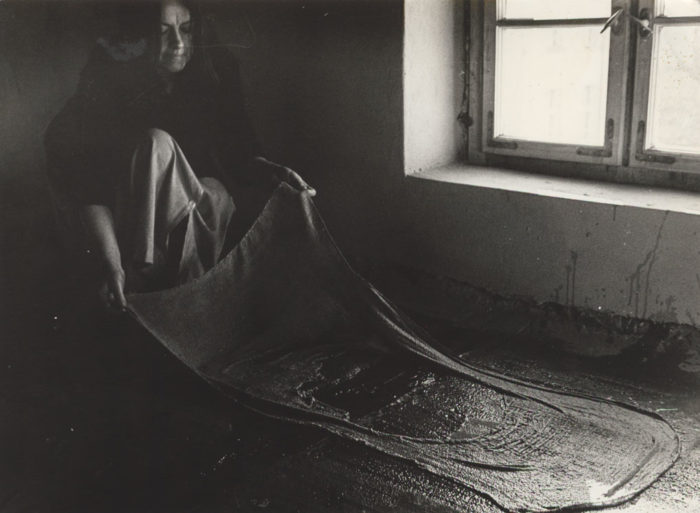

Teresa Murak, Visitant Nuns Floor Cloths, 1990. Documentation of performance at Hotel Sztuki, Łódź. Courtesy the artist

Resonance

In creating this exhibition, I was guided by art that resonates with feminist conceptions of labor, production, and reproduction. Its herstorical tradition comprises the second wave of feminist movements and the corresponding feminist avant-garde in the “former West” in the 1970s. Engaging with that tradition is contemporary art that problematizes the structural ties between the globalized exploitation of feminized labor and other forms of oppression and solidarity.

Taking account of these artistic positions and the references to herstorical events processed through these artworks, all of which came together to generate the exhibition, I juxtaposed them in a manner that can be referred to metaphorically as a resonance. It involves staging meetings that never took place: encounters between different, intergenerational, and geopolitically distant artistic and theoretical practices. It is the creation of relations that can be activated by movements, vibrations, or tremors of individual elements, and by the consonance between them. This method stems from a belief in the urgency of producing different, non-patriarchal herstories and perspectives. This, in turn, necessitates a search for creative links, repetitions, and flows, and the amplification of shared voices; it requires us to make cuts and bifurcations wherever the desire for sisterhood is blocked by majoritarian patriarchal social machines, which include historical and art institutions. Sisterhood rejects the linear depiction of time as a tool used by patriarchy to discipline imaginations for the purposes of the dominant growth ideology. Sisterhood is a machine of minor history, one whose vibrations are shattering the majoritarian, dominant canon of culture. While nurturing singular testimonies, peculiarities, and differences in artworks and artistic stances, sisterhood at once opens up to them the contemporary political horizon. The metaphor of resonance is also a working term for one of the methods employed by the staff of the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź in their efforts to update selected phenomena of the past that are mediated through works of art. This method was tested through tacit, intuitive combinations, or was termed an atlas, montage, constellation, etc., in the permanent exhibit of the collection Atlas of Modernity [Atlas nowoczesności], among others, and in temporary projects such as Eyes Looking for a Head to Inhabit [Oczy szukają głowy do zamieszkania] (2011), The Museum of Rhythm [Muzeum rytmu] (2017), Moved Bodies: Choreographies of Modernity [Poruszone ciała: choreografie nowoczesności] (2017), Katarzyna Kobro/Lygia Clark (2009), Afterimages of Life: Władysław Strzemiński and Rights for Art [Powidoki życia: Władysław Strzemiński i prawa dla sztuki] (2010/2011), and Correspondences: Modern Art and Universalism [Korespondencje: sztuka nowoczesna i uniwersalizm] (2013). What these explorations have in common is their anachronistic juxtaposition of artworks in publications and exhibition spaces for the purpose of constructing a subjective, contextualized sense of “now” through which we can examine the meanings of past events.

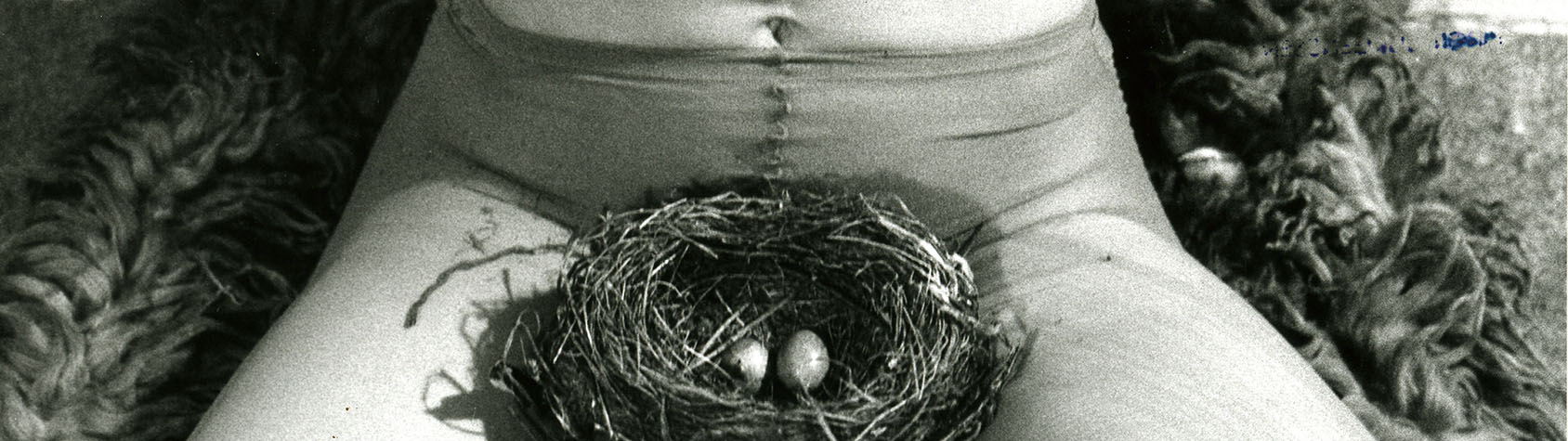

Jo Spence, from the series Remodelling Photo History, 1981–1982. Collaboration with Terry Dennett. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery, London. © Estate of Jo Spence

“We want and have to say that we are all housewives, we are all prostitutes and we are all gay, because until we recognize our slavery we cannot recognize our struggle against it, because as long as we think we are something better, something different than a housewife, we accept the logic of the master, which is a logic of division, and for us the logic of slavery.”—Silvia Federici, Wages against Housework, 1975

In the case of All Men Become Sisters, I identified in radical feminist art an overarching, complex idea that combined the rejection of the exploitation of women with the rejection of exploitation in its other forms. The purpose of the thematic assemblage comprising selected examples of this tradition and contemporary artworks was to distill the power of these acts of resistance and to imagine their possible consequences. Against this backdrop, there emerged a polyphonic herstory of the transformation of labor and its future in the ecological perspective. Thus created exhibition provided the possibility to combine and recognize already existing resources to prefigure sisterhood as feminist politics.

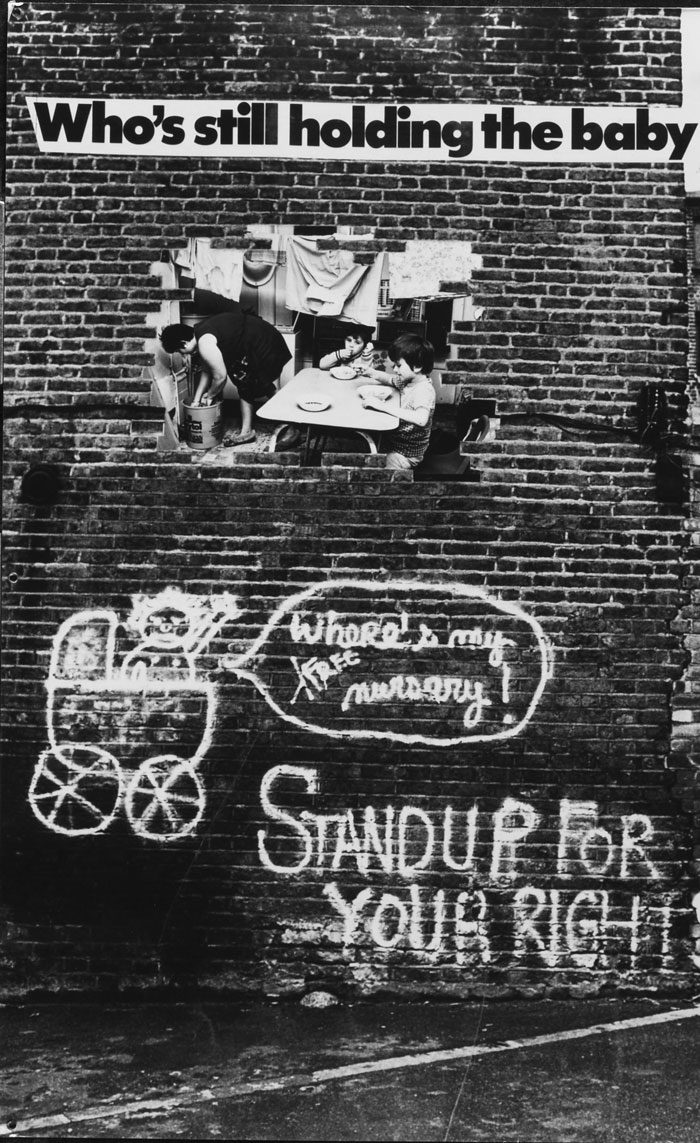

Hackney Flashers, Who’s Still Holding the Baby?, 1978. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery, London. © Hackney Flashers

Sisterhood

The problem of women’s invisible work and our role in social reproduction serves in the exhibition to shatter the violent abstractions and claims of universality made by dominant groups, by means of which they obscure specific instances of the exploitation of the subjugated. The title comes from a poster by Allan Sekula titled Alle Menschen werden Schwestern (2007), which the artist created as a visual expression of support for the alter-globalist protests against the G8 summit in Heiligendamm. The poster depicts a Mexican dockworker, while the title references feminist interventions in the call “All men become brothers” from Friedrich Schiller’s Ode to Joy [An die Freude] (1785), which has resurfaced repeatedly in various Western narratives about the liberation of the oppressed, before finally settling comfortably into the anthem of the European Union. The poster announces that sisterhood transcends the boundaries of biological sex in its search for alliances and solidarity. As feminist and postcolonial perspectives remind us, the flip side of the ideals of fraternity, equality, and liberty—the heritage of the Enlightenment—was invisible slave labor. This work was performed in European colonies and is now carried out in the contemporary exploitation spaces of the neocolonial economy, and, free of charge, in households by women, who have been excluded from the dominant concept and practice of the public sphere and classical economics.

Agnès Varda, Women Reply: Our Bodies, Our Sex, 1975. Courtesy of Ciné-Tamaris, Paris. Photo: Piotr Tomczyk, Archive of Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź

Nevertheless, sisterhood does not give up its attempts to consider that which is shared and common. It is adjacent to insurgent universality. Cinzia Arruzza uses this term in reference to feminist politics that view gender inequality as linked to the historical universalization process that is a product of capitalism. A critique of patriarchy should therefore be accompanied by a project for changing the dominant economic system. Sisterhood does not focus, therefore, on the emancipation of women as an essentialist concept, but instead perceives the struggle against patriarchy as a battle that is waged by molding the living environment into one that is more bearable to many subjects encompassed by the post-capitalist political horizon. It seeks a community that is malleable, empathetic, and continually verified and negotiated by specific, embodied experiences of difference. It must also consider as such the testimonies of the oppression of women under past socialist systems, as well as testimonies of the changes stemming from the global division of labor, particularly with regard to the care economy.

Wages for Housework

As the exhibition suggests, the questioning of the sex-based division of labor and oppression normalized by the patriarchy—a challenge mounted by activists, theoreticians, and artists associated with second-wave feminism—turned out to be subversive in the long run, reaching beyond their own moment in history. Among the most important consequences of this process was the revelation and politicization of the sheer amount of labor performed by women in the ostensibly private sphere of the family and household. In Italy in the 1970s, Silvia Federici, Selma James, Brigitte Galtier, and Mariarosa Dalla Costa proposed that, as part of the Wages for Housework movement, the program of the struggle against capitalist exploitation be expanded to include unpaid housework done mainly by women: emotional, physical, and sexual services. The demand that wages be paid for housework was not a step towards the commodification of these services or an attempt to prevent the happiness and personal satisfaction that could potentially be derived from performing them, but a step towards a greater awareness that they had become an invisible part of the economy, a means of reproducing the workforce and, by extension, capitalist social relations. Like other activists associated with Marxist feminism, those involved in this movement also observed that the wage labor carried out by women reinforced their subjugation and exploitation, and was often a devaluing extension of the naturalized service and care functions they performed in the patriarchal family. Marxist feminism and the social reproduction theories developed in the 1970s and ’80s expanded the understanding of capitalism to include subjects and processes that had previously been regarded as “extra-economic,” though critical to its operation, a subject Joanna Bednarek, Marina Vishmidt and Siona Wilson analyze more closely in their essays in this book.

Ines Doujak and John Barker, Loomshuttles/Warpaths, NOT DRESSED FOR CONQUERING 01 FIRES, 2012/2015. Photo: Piotr Tomczyk, Archive of Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź

Exhibition view All Men Become Sisters, Photo: Piotr Tomczyk, Archive of Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź. Exhibition design: Krzysztof Skoczylas

“We recognize within ourselves the capacity for effecting a complete transformation of life. Not being trapped within the master-slave dialectic, we become conscious of ourselves; we are the Unexpected Subject. […] The women’s movement is not international but planetary.”—Carla Lonzi, Let’s Spit on Hegel, 1970

As feminists have demonstrated, the cheapness or slave-like character of feminized labor hinges on the invisibility of these constituents. In this exhibition, feminist thought resonates with forces that challenge an economy that valuates the entirety of life’s processes in terms of the extraction of surplus value. Some of the artworks on display directly illustrate or contribute to the above discussions and strategies, while others resonate with them through the use of artistic means that resist contemporary discourses, expand them, reveal their limitations, or shift them into new spatial and temporal contexts. Moreover, I arranged the artworks so as to emphasize the intersections and interdependencies of various scales of perception, intertwining intimate perspectives and singularities with panoramas, intentionally political collective manifestations, and interlacing stories involving the city of Łódź, where the exhibition was held, with depictions that shed light on global interconnections.