Hardcore as Folklore

The still-to-be-defined cultural legacy of the genre and its complex relationship to traditional understandings of mass and subcultural identity

In music, a capriccio is a composition that takes a free-form approach to tempo and style. In painting, it refers to an architectural fantasy in which buildings and archeological ruins from different geographies and temporalities are placed together to form plausible, yet fictional landscapes. Gesturing to these connotations, the exhibition Capriccio 2000 traverses electronic dance music cultures in millennial Italy—particularly hardcore—to propose a sensory tableau: of listless bodies, ritualized gestures and neon hues amidst the detritus of suburban life. While several earlier instances of nightclub and rave culture have been canonized as spaces of resistance, hardcore, arriving in the 1990s, had a much more diffuse and nihilistic aesthetic. Directly interacting with mass cultural consumption from its onset, hardcore developed into a popular musical language in the early 2000s, proliferating within local youth scenes across Europe. Considered low-brow and folkloric by most, hardcore speaks to a unique cultural moment that arose from often overlooked geographies. This essay has initially appeared as part of the publication accompanying the exhibition curated by Rosa Tyhurst, Jeppe Ugelvig and Hannah Zafiropoulos in the context of the 13th edition of the Young Curators Residency Programme by Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, coordinated by Lucrezia Calabrò Visconti.

Compared to techno and house, hardcore is a type of electronic dance music still waiting to be fully understood. Low-brow, peripheral and nihilistic, it stands in stark contrast to the cultures surrounding its related genres, now firmly canonized and critically recouped for their social, political, and musical importance to cultural history.* Conventionally regarded as non-queer, non-black, and non-urban, hardcore is, in fact, antithetical to the three things that have historically defined electronic dance music. Even so—or perhaps exactly because of this—hardcore seems to have seeped into the aesthetic subconscious of continental European youth culture in the new millennium, becoming integrated as a part of a mass-cultural vocabulary. From the enduring appeal of hardcore-derived millennial pop stars such as Gigi D’Agostino and The Prodigy, to the ambivalent embrace of hardcore fashion aesthetics in Berlin’s nightlife and beyond, not to mention the ongoing proliferation of new hardcore genres (such as speedcore, gabber, and happy hardcore) across the world: the aesthetic motifs of hardcore continue to circulate and drift, garnering new social associations and political meanings. Hardcore, I want to propose, may slowly be developing into its very own example of European folklore, complete with its own set of myths, fantastical motifs, and fabled characters.

*I am referring to the important historical work being done by historians, artists, writers, and DJs on contexts such as the underground queer dance floors of 80s New York and Detroit, the “Second Summer of Love” and the rave scene of 1989s Europe, as well as the intellectualized techno sound coming out of post-Wall Berlin. See, for example the 2016 exhibition and book Energy Flash – The Rave Movement curated by Nav Haq at MuHKA in Antwerp; the 2018 exhibition Night Fever. Designing Club Culture 1960 – Today curated by Jochen Eisenbrand, Catharine Rossi and Katarina Serulus at Vitra Design Museum and ADAM; as well as writing and artworks by the likes of Simon Reynolds, Jeremy Deller, Jenn Nkiru, Mireille Silcott, Carleton S. Gholz and Iara Lee.

While comprising a wealth of local and disconnected sub-genres, the notion of “hardcore” first emerged between Frankfurt and Rotterdam in the late 1980s, pioneered by DJs Paul Elstak and Marc Acardipane. There, the hardest edge of Detroit techno and UK acid house fused into an accelerated industrial sound, abundant in melodic distortions, aggressive kicks and synth stabs at around 180 BPM. From its onset, hardcore was reactionary to the fashionable and opulent party scenes of metropolitan cities like Amsterdam and London, cladding itself in a working-class, anti-fashion aesthetic. Instead, hardcore embraced and celebrated an un-intellectual, hedonistic and rural machismo, speaking directly to a mass market of young Europeans in search of pure entertainment. Early tracks such as Mescalinum United’s We Have Arrived, Euromasters’ Amsterdam, Waar Lech Dat Dan? and Second Phase’s Mentasm echo this affect of nihilistic destruction, privileging overdriven bodily endurance over any aesthetic cohesion.

Unsurprisingly, hardcore was shunned by the techno and house establishment, which only served to feed its popularity and proliferation across Europe, where it formed new variations (such as “skizzo” in Belgium and “bretter” in Germany). In his book Generation Ecstasy (1998), music journalist Simon Reynolds considers hardcore a genre of electronic dance music entirely separate from house, garage, and techno, “designed for one-shot raves and for clubs that cater to rave-style teenage bacchanalia.” He explains that while the term has meant different things at different times in different parts of the world, “hardcore” has always designated “those scenes where druggy hedonism and underclass desperation combine with a commitment to the physicality of dance and a no-nonsense approach to making music (‘tracks’ rather than ‘songs’).” The raw, transgressive and alienating sound—often featuring blatant drug references—shocked outsiders, who began rendering it as a kind of fin-de-siècle punk movement. Indeed, hardcore distanced itself from the androgenizing and free-love aesthetic of the late 80s rave movement, and (re)masculated dance culture by recalling the militaristic and sadomasochistic imagery of other musical genres, such as trash and death metal.

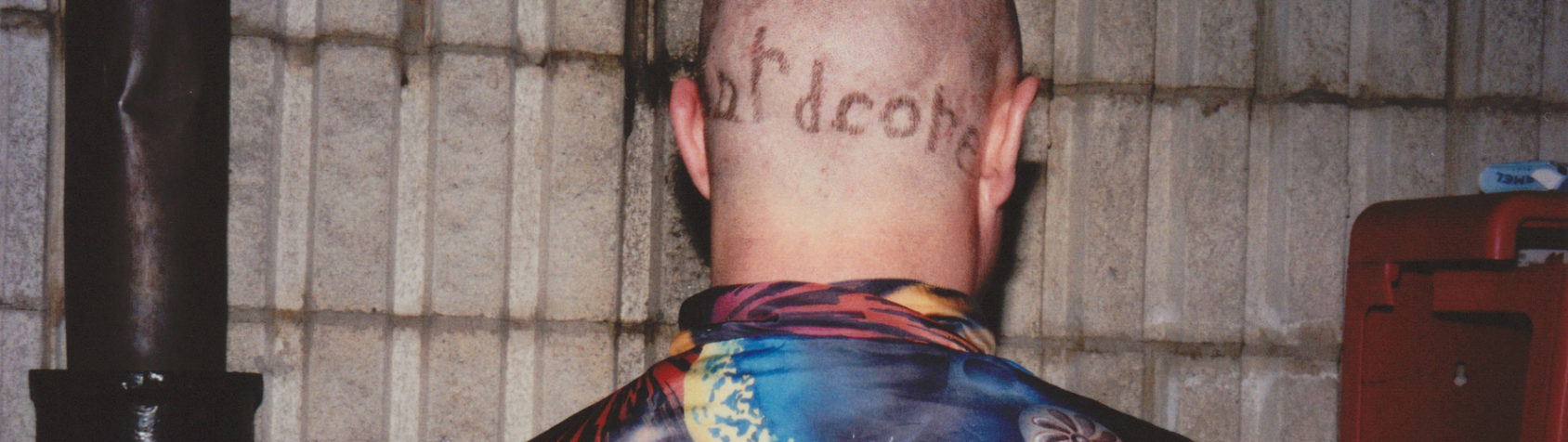

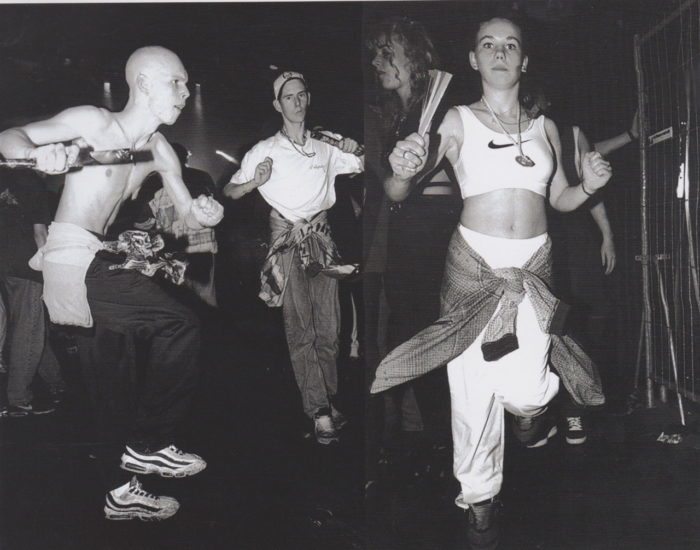

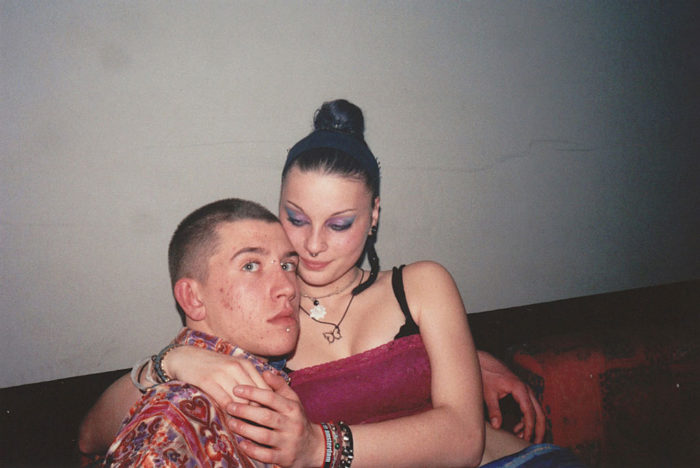

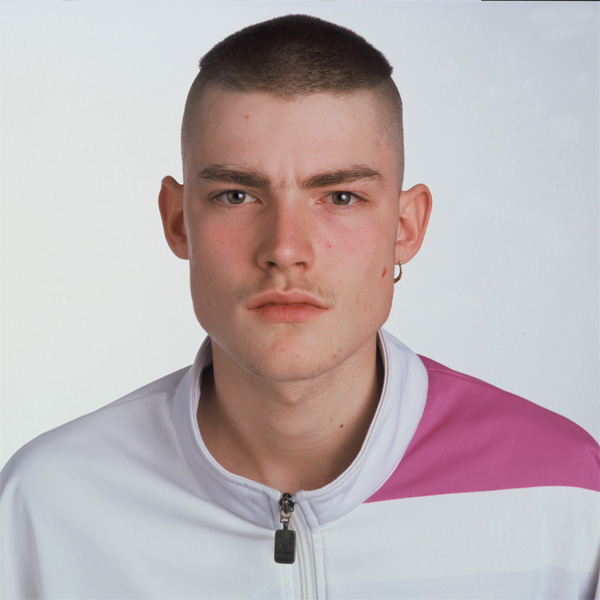

Courtesy Gabber Eleganza

Both sonically and sartorially, a distinct class motif has been ascribed to the hardcore sound and aesthetic. Hardcore’s one-dimensional and almost childish intensity is often affiliated with the deprived, post-industrial landscapes of Europe, while its participants—dressed in cheap sportswear, and with soft skinhead references—are often referred to as an embodiment of the “chav,” “tamarro,” “dresiarz” or “proll” aesthetic. In Italy, for example, the northern region of Pianura Padana became a hub for the hardcore sound in the late 1990s, as it gained traction in enormous “super clubs” along the A4 highway from Bergamo to Venice (connecting the cities of Brescia, Verona, and Padua). Similar examples can be found in other European nations such as Belgium, Germany, the UK, and the Netherlands, as well as in the many European regions devoid of any notable “party capitals.” While house and techno can be understood to echo the glamour and pseudo-intellectualism of metropolitan life, hardcore evokes the boredom of rural youth, disenfranchised after the decline of heavy industry, committedly consuming “trash culture,” and forever attracted to undying cultural imagery featuring death, destruction, and anti-religion. “… hardcore is closer to heavy metal,” Reynolds argues again, “Both are scenes that just won’t die, fulfilling as they do very basic and enduring needs for provincial youth.” In these rural areas, characterized by strong unemployment and little job security, hardcore was also embraced by right-wing and pseudo-fascist youths, who drifted to the working class machismo of its aesthetic and integrated it with their superficial, yet extreme ideological beliefs.

Courtesy Gabber Eleganza

Hardcore and its regional derivatives can be (and are, by some) historicized as the “last” musical subculture of Europe before the arrival of the internet, yet its early connection with mass media consumption complicates a reading of it as “classic subculture.” This problematic is not reserved to hardcore, but to late 20th century dance music communities in general. In her 1995 book Club Cultures, Sarah Thornton uses the example of European rave culture to challenge traditional theories of subculture, such as those by Dick Hebdige, who, through his early reading of punk, instilled a general conception of avant-garde subculture as always standing in opposition to the mainstream: resisting through ritual, subverting through style. This abstract idea of a “critical underground” premised on differentiation from the masses allows for the discovery of symbolic resistance pretty much everywhere, Thornton argues, even when such resistance stands in direct interaction with mass culture. If such an opposition between avant garde-versus-bourgeois, subordinate-versus-dominant, subculture-versus-mainstream culture was ever possible, from the 1990s onwards, she highlights, the distinction between subculture and mainstream becomes fully obsolete, with “low,” “middle,” “high,” “working-class,” “elite” and “mass” culture pluralizing and bleeding into each other at ever greater speed. Globalization and a rapidly changing media landscape allowed for ever-faster virality, demanding new theories of youth culture that emphasizes movement, circulation, and flexibility.

Not coincidentally, the 90s was the time of Michel Maffesoli’s popularized theory of “neo-tribalism,” where the French theorist announced the break-up of mass-culture and the breakdown into micro-groups of lifestyles and tastes across class positions, brought together instead by affect and new forms of sociality (such as music). In those years, the term “tribes” emerged as a colloquialism for the members of localized European techno and rave movements who began traveling across the continent for parties. The strong romantic and affective dimension of this new era of “tribal” youth culture, connecting and interacting through a rapidly globalizing media landscape and facilitated by easier modes of travel, entered into a kind of feedback loop with the mass market, which began to render subcultural identities as interchangeable commodities. As trend forecasting group K-Hole has examined, this mode has extended into the 21st century: “…being different isn’t always a lonely journey;” they write in their 2013 text Youth Mode, “it can be a group activity. Whether you’re soft grunge, pastel goth, or pale, you can shop at Forever 21. Identities aren’t mutually exclusive. They’re always ripe for new combinations.”

Anna Adamo, Gabber, 2014-2015

Anna Adamo, Gabber, 2014-2015

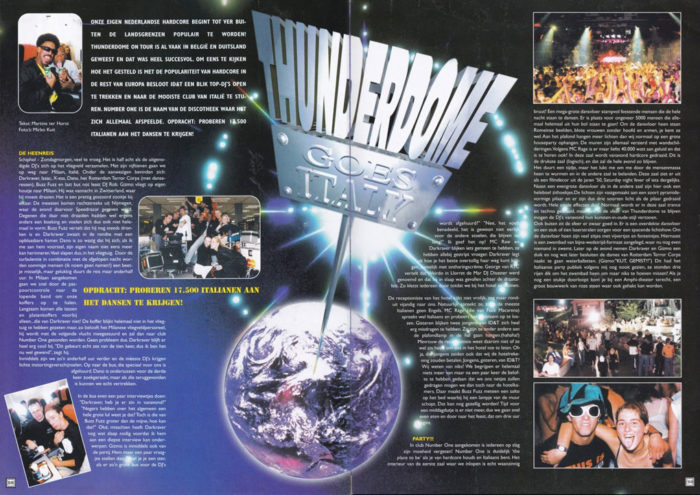

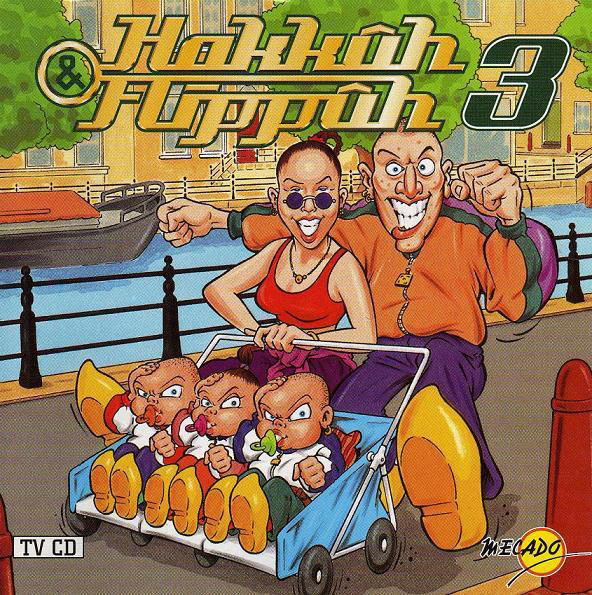

Hardcore evokes this postmodern collapse of cultural and identitarian specificity through consumption, emerging as it did as a “trend” or “style” more so than any defined underground movement in the mid-1990s. As Thornton recounts, by the early 1990s the extensive coverage (and moral panic) of acid house culture spawned a “new mainstream” of rave music for the masses, premised less on embodied participation (going to a rave), and more on direct aesthetic consumption (through media). Compilation albums of hardcore such as Hardcore Ecstasy and Steamin! – Hardcore ’92 rose to the top of European music charts between 1990 and 1992, rendering the genre a completely mainstream phenomenon. These years saw the rise of commercial mega-raves and festivals in the UK and Europe, most significantly the Thunderdome franchise of parties and CD compilations by Paul Elstak’s entertainment company ID&T. While the genre proliferated across the world, new regional derivatives continued to form and flourish, including jungle in England, and the ultra-fast, super-aggressive gabber in the Netherlands—“the ultimate bastardization of techno”—which in turn spawned local flavors in several European regions such as Italy, Spain, and Austria. While the Dutch music magazine Update declared the death of the genre in 1998, this in fact only marked the beginning of its entry into mass culture. In 1999, Belgian menswear designer Raf Simons presented his SS00 collection, abound in MA-1 bomber jackets and buzz-cuts, as a tribute to the then already mythological gabber aesthetic, marking the beginning of its normalization into both men and womenswear. That same year, the Italian DJ Gigi D’Agostino immortalized the hardcore sound with his deeply romantic pop club anthem L’Amour Toujours, which topped charts across the world.

With over thirty years of endured presence in European music culture, hardcore can no longer be understood as a mere trend or fad, but qualifies instead as a kind of abstract aesthetic motif recognized by a broad range of Europeans born in the last two decades of the 20th century—from the right-leaning hooligan of the suburbs to the fashion worker of the metropolis, crafting fashion editorials that glamorize its pseudo-skinhead aesthetic. Hardcore escapes any sub-cultural origin or locus, allowing for the endless multiplication of its aesthetic in local and regional environments. Still, it is prone to romanticization and appropriation as style in the way that “traditional” subcultures such as hippie and punk have been before it. Precisely because of its diffused or generic quality, hardcore instills a sense of belonging or nostalgia in a large group of people, who appropriate its aesthetic in both direct and subtle ways. In the gay European nightclub, for example, the latent homoeroticism of “bro-y” hardcore moshing (“lads” stripped to the waist in a feat of trance-like endurance) may be isolated and celebrated as gay culture, while never fully erasing the traces of its related (homophobic, racist) contexts of signification. Similarly, the high ponytail, sports bra, and MA-1 bomber has become a go-to uniform for the international female social media influencer of the late 2010s, perfectly fusing a remnant of the underground with the pragmatism of contemporary sportswear. Just as metal and hippie aesthetics informed the nostalgic fashion of naughties hipster aesthetics 10 years ago, today, millennial hardcore constitutes the stylistic nostalgia of a new generation. At the same time, hardcore remains widely affiliated with the aesthetics of rural pseudo-fascism, right-wing hooliganism, Nordic outlaw motorcycle gangs, and English white power skinheads.

Bureau d’études

Bureau d’études

These plural, contradictory, and mythological connotations of hardcore—escaping exact definition, yet seemingly omnipresent as an aesthetic motif—perfectly qualify it as a kind of folk culture. Folk can be described as the general narratives and motifs of a culture that circulate calmly among its members without any specific place of origin. Often based around myth and ritual, and evoking traditionality, irrationality, and rurality, folklore is an expression of the everyday in aestheticized terms, facilitated through cultural communication and exchange without any structured sense of authorship. US folklorist Bruce McClelland, for example, defines folklore as “communicative behavior whose primary characteristics … are that … it doesn’t ‘belong’ to an individual or group … and in the modern context therefore transcends issues of intellectual property; … it is transmitted spontaneously, from one individual (or group of individuals) to another …, frequently without regard for remuneration or return benefit. As it is transmitted, it often undergoes modification.” Adding to this, communication theorist Robert Glenn Howard explains that “what is essential about folkloric expression is not a ‘traditional’ origin. Instead, it is … ‘continuities and consistencies’ that allow a specific community to perceive such expression as traditional, local, or community generated.”

As Jacques Attali recounts, it was Claude Lévi-Strauss who first argued that music, along with the novel, has become a substitute for myth in modern society, if myth is defined as the production of a code by a message, of rules by a narrative. The ritualistic, aesthetic, and social elements of music culture make it an important mirror and tool for understanding the modern world, he posits: in fact, it reflects the very manufacture of society. In his 1977 text Noise: The Political Economy of Music, Attali examines music’s evolution from ritualized social form to specialized practice, eventually culminating in its mass consumption as a fetishized commodity, “stockpiled until it loses is meaning.” Yet, it is exactly within this frenzied landscape of sonic manufacture and consumption that we must decipher and extrapolate a meaning of contemporary capitalist society.

Hardcore allows us to see the connectivity of recent European society through the intertwined processes of capitalist youth consumption and media circulation, exemplifying how such circulation acquires the patina of nostalgia through time. Indeed, the more recent emphasis on transmission and circulation in folklore studies has come to highlight the role of media technologies, such as print, in the formation of romantic cultural myths. “Mass culture uses folk culture,” concludes scholar Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, and “folk culture mutates in a world of technology.” Considering hardcore as folklore allows us to redeem its seeming banality to instead use it to decipher important affective codes of identity-formation, social dynamics and youth aesthetics in millennial Europe. With its own set of ever-permuting gestures, costumes, and legends, it challenges the way we may conceive of the relationship between high and low, dominant and underground, postmodernism and post-industrialism, even within the relatively slim history of electronic dance music.