Drawing the Pages of my Diaries High on Trichloroethylene

Porpora Marcasciano in conversation with Michele Bertolino

The conversation was recorded in Bologna on a sunny but cold December 3, 2022. The night before, Porpora Marcasciano—activist, sociologist, and key figure of the queer movement in Italy—performed Amore, arte e rivoluzione (Love, art, and revolution), a short lecture–performance about the 70s and 80s that fused her political fight within the queer and trans movement in Italy with songs, books, and encounters. The performance originated from the drawings displayed at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna for the exhibition curated by Michele Bertolino Non sono dove mi cercate (I am not where you are looking for me) from November 11, 2022, to January 8, 2023.

Michele: So, I’ll ask you some questions, shall I?

Porpora: Well yes. Or I can ask them myself… Who are you? Where do you come from? Where are you going?

M: These are difficult questions to answer, Porpora. I am all ears if you have any answers.

I can make it easier; let’s start with the drawings. The exhibition Non sono dove mi cercate, at MAMbo, in Bologna, brings together around 30 works, produced between 1973 and 1977 and then again between 1981 and the end of the decade. You started to draw at sixteen years old when you were living with your family in San Bartolomeo in Galdo and attending high school. In your village, a group of hippies had opened the Studio Uno Underground, a basement that was a social center, an art gallery, and a communitarian space. One afternoon you walked down those stairs and entered a new world.

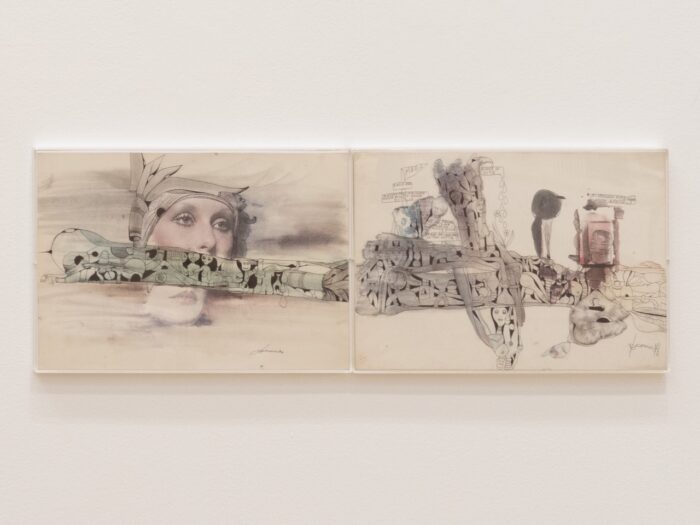

These drawings were made by Porpora Marcasciano between 1973 and 1975. Ph. Ornella De Carlo, MAMbo.

P: That’s true, but it’s not just the Studio. There are a series of joint causes. My initial political awareness came when I joined the political collective at high school. At the same time, at the Studio, I was discovering counterculture and anarchism. The two worlds combined; they were intertwined and not antithetical. Often we held the collective’s meeting at the Studio. Thinking back at the cultural and political movement that existed in that small village, I am amazed. I am not exaggerating when I say that there were at least a hundred of us, forming a sort of locale. For me it was a breath of fresh air. I was coming out of a period of great suffering—today we would talk about bullying, but at the time we lacked the right words. They were hounding me; they were after me. The Studio and the collective instead gave me happiness; they were spaces and bodies that encouraged me. Of course, the Studio was what intrigued me the most; it was run by these guys who had just come back from a trip to India. Everything was new: long hairs, necklaces, bracelets…

M: Did you have long hair back then?

P: Not yet, that was when I decided to grow it. Then of course, I always had the problem that my hair grows slowly—except when I was doing hormones. I started to dress in a certain way—I used to rip my jeans or to put on sheepskin jackets.

My parents had a grocery shop; I would get food from them and bring it to the Studio. When you walked into that basement there was always smoke, a rarefied haze of cigarettes, weed and smoke coming from a chimney. You had to go down the stairs and you would find yourself in this salon with some big tables; I can still see them. You would sit on cushions on the floor and you would draw. We all used the same technique, then; everyone had his or her own way of approaching it. Totò Reino was definitely the best one. He studied at the Academy—it would be nice to see those drawings today, but unfortunately he left us two or three years ago. Then there was Giorgio, who went out with the acids. He lived in Christiania, in Copenhagen, and when he came back to the village he was always bringing some news. Others lived very often in Lausanne in a social center that was a hub for all those who were wandering the world. Then there was Salvatore, who was with Re Nudo and Macondo in Milan. There was a good atmosphere of ideas and stimuli. There, I literally began to travel. In my mind, I was already in India and Morocco, everywhere, on the roads of the world, with my backpack on my shoulders, hitchhiking. And because I had already been drawing for some time, when I saw what they were doing at the Studio, I was impressed; and so I started; I locked myself in my bedroom and started to sprinkle some sheets of paper with trichloroethylene. After a while, it became unlivable, because trichloroethylene stinks and it hurts your nose if you inhale it for a long time. It also gets you high—I used to get high on trichloroethylene!

I would take the drawings with me on trips, trying to sell them – in those days, you would sell anything to make some money. The first trip they took was the first trip of my life, when in June 1974 I left for London. A three-day trip just to get there: several trains, a couple of buses and a boat. The drawings were there with me; the entire backpack was not enough. I must say though that I didn’t sell much there; I gave a couple of them to this group of girls who had clung on to me; they wouldn’t let me go! Luckily, they helped me, found me a home and a job. I used to take the drawings around Italy as well, especially Florence, which was one of my favorite destinations – and I remember I managed to sell a few there.

But it was all an alibi, part of the look, let’s say.

M: You talked about the beginning of your political commitment, the raising of a specific awareness. The high school collective was the first political space you entered—maximalist in its own way—and, on the other hand, the Studio, where you discovered counterculture, underground, a different way of living. There is an ongoing mixture in your life experience of a political awareness and a creative, artistic dimension, the intertwining of…

P: …of what would later become, in 1977 in Bologna, the division and interweaving between a transversalist creative area and another more political area, that of Autonomia or Lotta Continua and a thousand other smaller groups.

M: Which you crossed, obliquely.

P: In San Bartolomeo del Galdo there was no Autonomia, but the Manifesto-PSIUP was very present among young people. The Communist Party too, it was huge with lots of members. The old people in my village were all politicized; they were proletarians who were waiting for the communist revolution; they believed it would happen at any moment – they were people who suffered punishment and persecution during fascism. Often when I returned home from Naples I would bring them posters of Marx, Lenin or Mao and they were overjoyed. They had badges many proudly sporting Bakunin, manifesting a deep anarchist soul within the party, which at that time was looked at as very institutional. Yet, it was the 20th century, which ad an unrepeatable political dimension.

M: It’s true. The PCI was made of different souls, those more institutional and reformist—parliamentary, I would say—others Maoist, Leninist, anarchist. My grandfather was a member of the PCI; he had a bar in the village where I come from, and he was called “the Red”. He took part in the Resistance.

P: In Val d’Ossola?

M: No, not there. He was fighting in Val Po, close to his village, which had been set on fire by the Nazis. My grandmother, on the other hand, used to tell me that she hid the partisans’ weapons among the shrubs or the vegetables in her garden; she told me about her friends who were partisan couriers.

P: Oh, if you only knew… I too was a courier for years: from anarchists to hippies, from the Autonomi to… from one bed to another!

M: We’re jumping here too, traveling backwards. Let’s look again at the drawings. You mentioned you were using trichloroethylene, getting high with it. Perhaps we should clarify the technique, which was very common in that decade among street artists and hippies. You would pour some trichloroethylene onto a sheet of paper and then rub some newspaper or glossy sheets onto it. They would release their colors. This would create shapeless masses of color that were then the starting point for tracing lines and drawing, almost as if you were looking for order in such chaos.

These drawings were made by Porpora Marcasciano between 1973 and 1975. Ph. Ornella De Carlo, MAMbo.

P: As you say, first there was the mass of color, which formed according to the movement of my hand onto the paper. From the blobs of color, I would then draw the first lines with the ink. Sometimes they wouldn’t satisfy me and so I tore them out, or others were finished in an hour or two.

M: The arrangement and shape of the stains indicated to the hand where to move, and then there was music…

P: A lot of music, songs were always there. You saw the shapes: pipes, links, knobs. I was trying to draw a system that we didn’t want, that we rejected, or fought; or, on the contrary, I was trying to sketch the imagery of an idyllic utopian world that we were all dreaming about together and were trying to build.

M: There is a drawing from 1973, among the earliest ones, of what look like elongated guts…

P: Hmm… Is there?

These drawings were made by Porpora Marcasciano between 1973 and 1975. Ph. Ornella De Carlo, MAMbo.

M: Between the bolts and tubes there are some comics. On one side you write: “I, death, am stronger because I won over life”, “I was born to die”, “Humankind here your life ends”. Then, a few drops fall on two weak little flowers, and there you write “drops of life”.

P: Those drawings originate from Paradise Now by Julian Beck and Judith Malina. They collect almost a manifesto of the creative hippy anarchy. I don’t remember it literally, but it sounds something like “I want to walk around naked without any problems”; “I want to travel the world without a passport”; “I want to love who I want and when I want”. Those sentences represented pure joy for me. In the drawings, I was reporting what I was thinking while reading it. I was 17 years old. They collect spontaneous, immediate thoughts.

M: There is naivety, a first glimpse into a new world…

P: Sure there is, because I started out of the blue. The collective fostered my political commitment and the Studio taught me drawing techniques and introduced me to a new culture, like Paradise Now. You know that it was the first book I picked up when I first entered the Studio, and I immediately immersed myself in these sentences. My head exploded. Then there were long, philosophical conversations. There was this guy, a neighbor, a little genius who was creating machinery and experimenting a lot with the drugs. His tone of voice was slow, thoughtful. He was always making speeches that were upsetting to me. I would replay them in my head for days. It was all new; I had never thought about it. I had lived immersed in the culture of my country, without understanding it. It was destabilizing for a poor child like me.

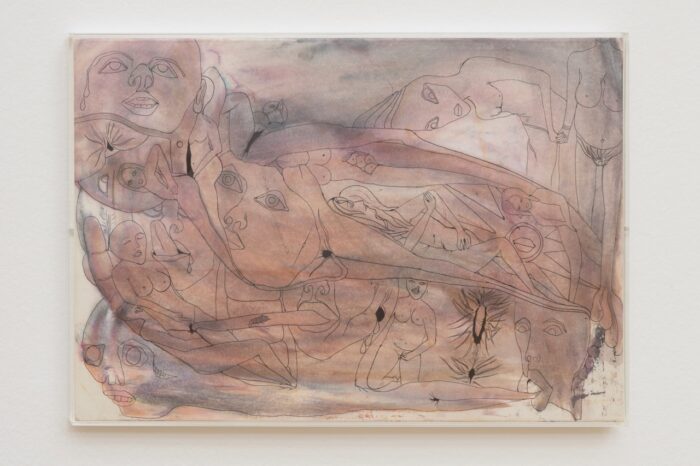

M: You often tell me that when you look at your drawings, you mainly see aesthetic signs or documents of a moment, little else. The first time we opened the folder where you store them, it was as if a generational imaginary opened up before my eyes. Not only is there a mechanical system that constrains and crushes you, but in these connections, communions, penetrations, I see bodies coming together. I would say, a utopian…

P. Utopian, sexual and sensual entanglements. Because there you glimpse the quest for my identity and sexual orientation. We were coming out of centuries of oppression, and it was not obvious to identify as homosexual, let alone as a trans person. Sure, since I had found my place, I flaunted it. Yet, I wasn’t openly saying it. The first time, it was during an assembly in 1975, just after Pasolini’s murder. I was brazen; I had sexual relations with almost all the boys in the village. With the guys from the collective and the Studio it was different; the relationships were something more; perhaps it was love. I abandoned guilt—there was pride.

Courtesy Porpora Marcasciano. Ph. Ornella De Carlo, MAMbo.

M: I see it in the mouths, in the hands that become phalluses, vaginas that turn into eyes, breasts and mouths, a union, even when disorganized, a quick moment, the interlocking.

P: You are not taking into account an important element: we now live in the age of social media, of the immediate; I would say of the metaverse. Back in those days, these encounters were stolen moments: I was stealing something that otherwise would not have been possible, feasible. It was transgression. At least, for me it was. I don’t know if it was for the others—I guess for them it was something unspeakable.

M: Then 1977 arrived and you moved to Naples.

P: I should have gone to Rome, but I had a crisis of depression with strong anxiety and Rome was too far away. Naples was closer. Actually, I was in the city only for three months, because then I started to hang out with friends from the collective who were all living in Rome. I often went to Carmela’s, or to San Lorenzo. Then I moved to Rome in September 1977, thanks to my mother who found me a small room in Piazza Barberini. But even there I didn’t stay long; I was always in San Lorenzo, which was my place; my whole group was there, one in Via dei Volsci in front of Radio Onda Rossa and the other in Via dei Campani, in front of Anomalia, and this became my home, where I lived for six years. From there we wandered Trastevere, or Campo dei Fiori, in Piazza Farnese or Navona…

M: Your stories are always located in a precise emotional and historical geography. You tell stories by placing events in a space. You lived in a different Rome…

P: Yes, if you compare it to today. Everywhere you went, you would meet a community: I met Francesco Di Giacomo of Banco del Mutuo Soccorso, Dario Bellezza, Antonella Parigini. In 1974, I went to the city with a friend, Cognacchino—a handsome guy of dark complexion—Pasolini was still alive, and we met Maria Schneider and Gregory Corso. Renato Zero too, when he wasn’t famous but liked very much to crossdress. It was a worldly Rome, not one of elitism.

M: When you moved to Naples and then to Rome, you stopped drawing. It is as if life entered the room while you were bent over the sheets of paper and swept everything away. It is as if your attention was required elsewhere.

P: Well, you know, when I was in San Bartolomeo del Galdo I had a lot of spare time. The city upset me; there was so much to do, assemblies, demonstrations, concerts—a constant whirring! Until I settled down around 1980-1981. By then I was living alone in the house in Via dei Campani. Nocciolina, my flatmate and close friend, had committed suicide in 1979 – that was a heavy blow. Francesco, on the other hand, was always traveling. By then that was my home, I managed to find a space for myself.

M: “Spare time” or, one could say, “time to reflect, condense, reread”. In a way, the drawings became those moments of creative solitude for you, as if you were taking your time to write about what was happening around you, but in a different way.

P: The last thing I was doing was studying. Back in San Bartolomeo, I was attending high school, yet the professors were very politicized, and we had close relationships. The philosophy professor, a Maoist in an eskimo, was a profound person, and we often spent evenings together with my classmates to discuss with him. At university, too, I found it a stimulating world. I took my Anthropology exam with Pino Simonelli, with whom I had a love affair and who introduced me to the world of the femminielli. I studied Sociology of Art and Literature with a Marxist-Leninist professor, reading Lukács and the Living Theatre; it was like studying parts of my life for the exam. I remember one exam that was really shit. I was part of the political collective of my faculty, and we imposed the political exam for Philosophy of History: a monograph on the texts of Toni Negri, La forma Stato and Dall’operaio di massa all’operaio sociale. Reading Toni Negri at twenty was very difficult; to understand a page you had to read it over and over again for days. We really cursed that choice!

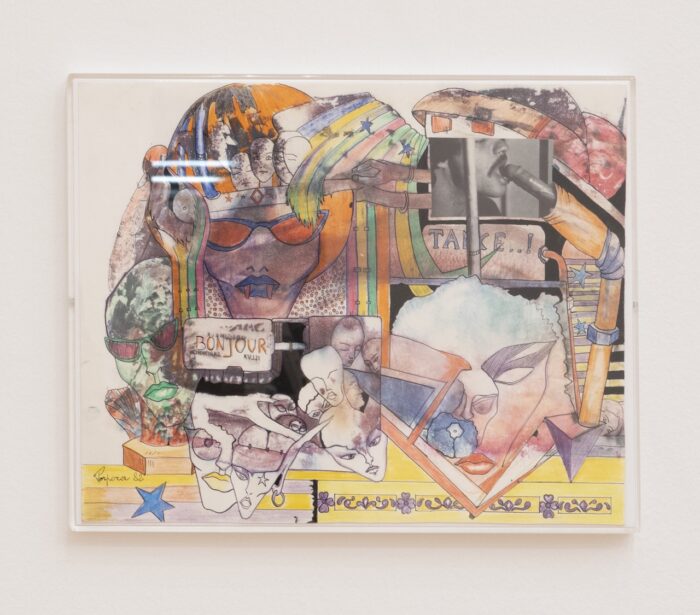

M: I would like to fly over, and approach the drawings again. We know what happened in ’77, and in the years that followed. As we were saying before, you started drawing again in 1981. This time, however, it’s all different: there are patches of color, sure, but the colors shine, the shapes are sharp, stars, comets, and lots of masks.

These drawings were made by Porpora Marcasciano between 1981 and 1986. Ph. Ornella De Carlo, MAMbo.

P: You mentioned the gap. When I started drawing again, I initially used a technique that was familiar to me, then I experimented with watercolor and collage. The drawings grew with my political and personal awareness. I had already joined the queer collectives; I had founded with Marco Sanna and others the Narcisco in Rome. I was familiar with the practices of the first gay movement. Then, punk arrived and I jumped into it; the clothes were unstructured; the colors were marked. I remember I used to wear really tight black leather trousers and then put on neon socks, yellow, fuchsia, and I used a lot of leopard print. Those were also the years of my lovers…

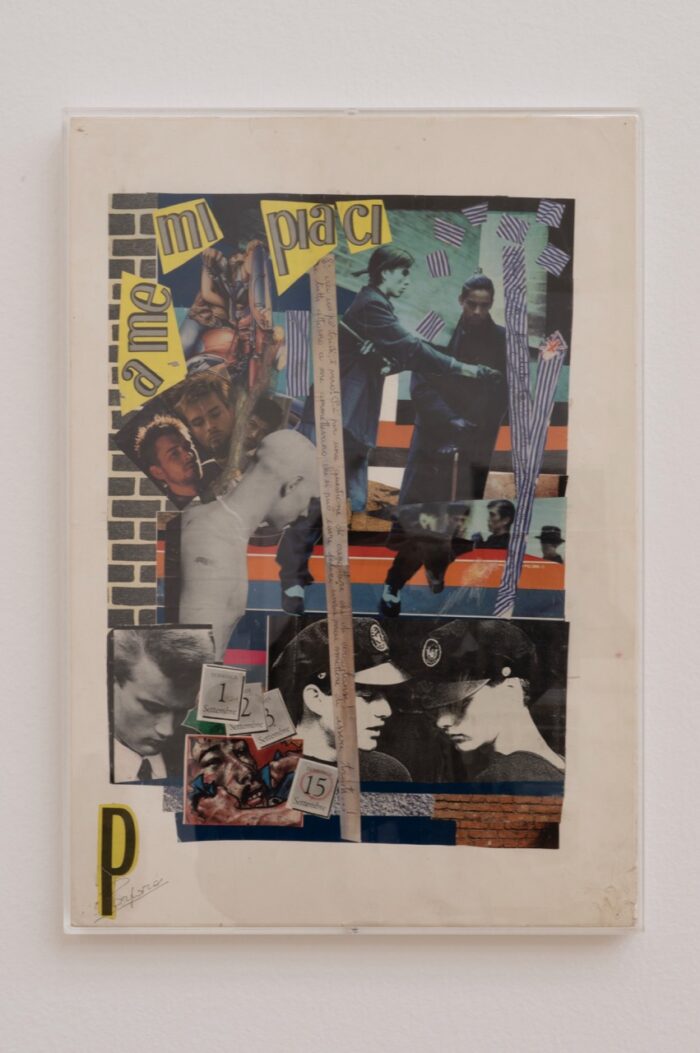

M: I’m immediately reminded of that collage…

Courtesy Porpora Marcasciano. Ph. Ornella De Carlo, MAMbo.

P: That coincided with the end of the love story with Luca. I was really sick, physically and mentally. It was a moment of strong melancholy and I decided to collect images that reminded me of him. Then I wrote some quotes from Alexis, or The Treatise of Vain Struggle by Marguerite Yourcenar. Then you can see some numbers, because with Luca there has always been a strange chronology.

M: The drawings from the 80s follow very closely the story of your life while you were living it, the spaces and experiences you were going through, what was happening in your everyday life.

P: They coincide with the beginning of my trans experience, the experiments with hormones, the street and prostitution. My life was changing drastically and with that my perception as well.

M: Yet there is always a link with earlier drawings. There is a drawing from 1977 where these experiences begin to appear. There is a female figure who seems like flying and above it a poem of yours: “Here is the wonderful woman, a fantasy dream. To be a woman is to understand why rain bathes us and to love it, because it is rain, and afterwards it will be sun and snow and wind and then always sun. The sun (sole) will be called alone (sola), alone (sola), only (solo) woman”. Her eyes are looking ahead.

You said that you travel with the drawings. I know they were shown in Bologna in 1982 and then again the following year.

P: Yes, they were exhibited during the ‘Presa del Cassero’ (the first public building that was given to a homosexual collective by the city hall administration in Bologna), three days of festivities. They knew I drew, of course they didn’t consider it to be art, but they thought they were nice and so they decided to exhibit them at Palazzo d’Accursio, on the first floor. Then, much later, I remember an exhibition at Calusca in Milan, when we were already organizing Facciamo Breccia (a committee for laicité and anti-fascism in the early 2000s). I think it was around 2007 or 2008. Nicoletta Poidomani, a comrade, had organized it.

M: Well, this is all new to me! I remembered the story at the Parco della Montagnola in Bologna in 1983. During a festival of the UDI (Union of Women in Italy), the drawing showing a photo of a blowjob was censored…

Courtesy Porpora Marcasciano. Ph. Ornella De Carlo, MAMbo.

P: Well, but I remember things bit by bit…

M: I’d like to collect the various pieces together, or at least try to. When you talk about your drawings, you don’t look at them as if they were works of art…

P: I don’t feel like saying they are my artworks. They are not my works; they are my diaries…

M: It is true, they are pages, in which experiences, reflections, your path intertwined with other paths, a life that is a thousand lives finds a way to tell its story. Yesterday night you were saying how there is no distance between the past and the present, but there is a continuity. You are convinced that one of the tasks that is ahead of us is the one of mending. Through these drawings, we are trying to mend moments, stories.

P: This work of historical mending is already underway; when we were talking, when we started thinking about the exhibition, we started to pick up the frayed links to mend them. But, it is a work that is always done together.

M: Do you want to add something, Porpora?

P: That I’m confused. Yet it’s a beautiful confusion.