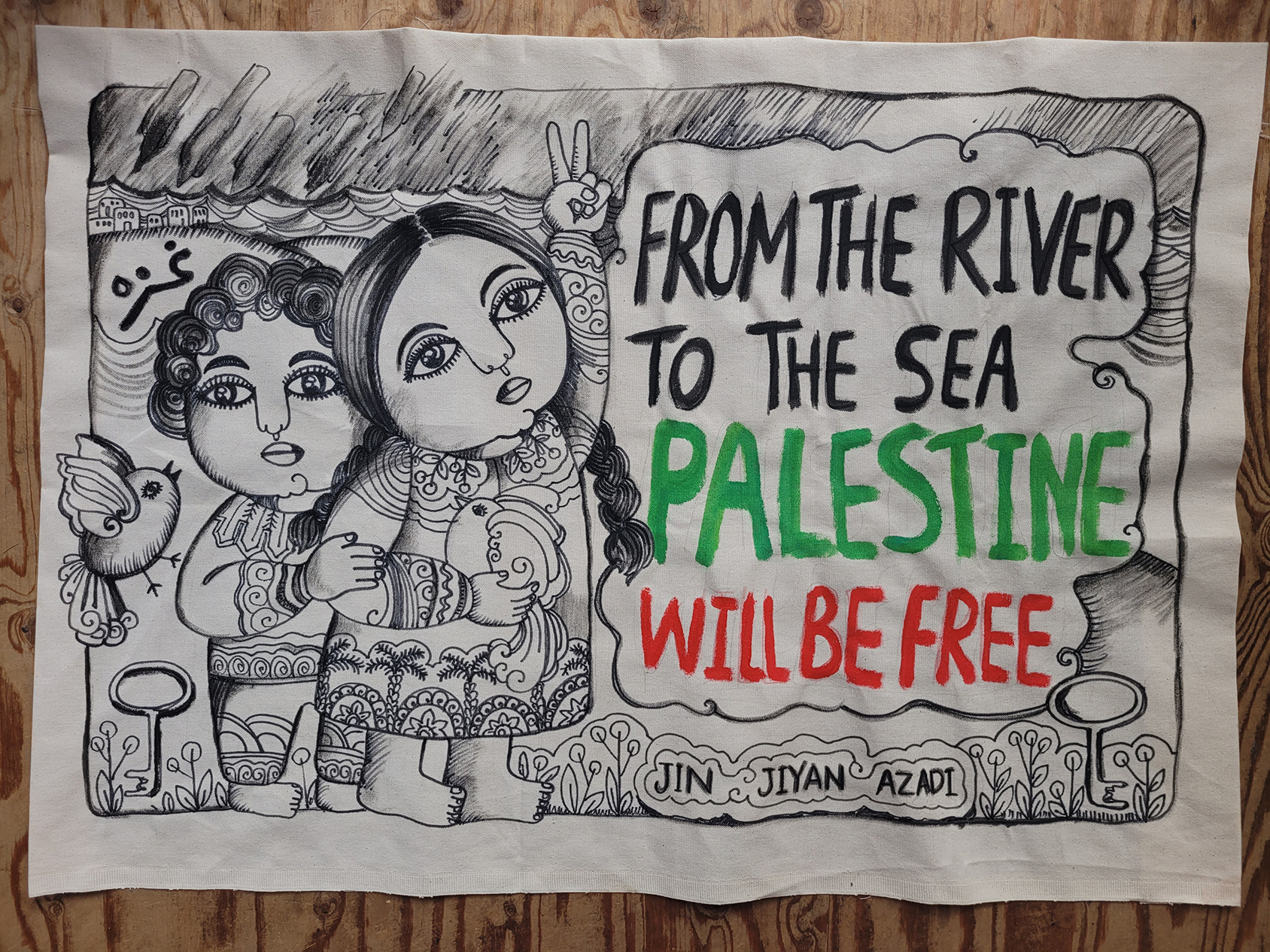

From the River to the Sea

Illustration by Golrokh Nafisi.

We need to stand firmly against what has been unfolding in occupied Palestine for over six hundred days, and for the last seventy-seven years—and the expansion of the invasion into Lebanon first, and now into Iran. All struggles are intertwined, but for many of us, Palestine is the beginning and the end of all our struggles, the image our minds tend to, when we think of liberation, of land, of belonging and return. Since we are all witnessing and mourning the escalation of the horrors unleashed by the most unbearable and blatant colonial and patriarchal imperialism and apartheid that Israel represents, the only weapon and relief we have had at our disposal is writing. So, we initially invited several writers to quickly draft some short texts in solidarity with the occupied and wounded land—people, poets of Palestine, and all the martyrs of this white bullyism, as we keep on condemning the hypocrisy and lies of Western media and governments.

You can still send your writings at [email protected]. But we invite you to join Boycott, Divestment & Sanction movements, protests, and donate, until this bloody empire falls.

For anyone who still needs to read more, and to access news that are unbiased, here a list of links and Instagram profiles to follow, collected throughout this past year:

Syllabus No Justice No Peace pad 1 & pad 2 by Madu and Sandra Cane

Palestine is Free (If You Want It) on The New Inquiry

FramerFramed‘s mixtapes, reading lists, podcasts and others

Country of Words: A Transnational Atlas for Palestinian Literature

Palestinian Youth Movement‘s depository

Settler Colonialism For Beginners a guide written and curated by @rowankatba

Palestinefilms.org Palestinian films and films about Palestine

Palestinian Feminist Reading List

Palestine Poster Project

On Mourning and Statehood: A Response to Joshua Leifer on Dissent Magazine

To say and think a life beyond what settler colonialism has made on MadaMasr

Vengeful Pathologies: Adam Shatz on the war in Gaza on London Review of Books

Hopeful pathologies in the war for Palestine: a reply to Adam Shatz on Mondoweiss

At the threshold of humanity by Karim Kattan on The Baffler

Can the Palestinian Mourn? by Abdaljawad Omar on Rusted Radishes

Farewell Germany by Ismail Fayed on Al-Jumhuriya

Once Again, Germany Defines Who Is a Jew | Part I by George Prochnik, Eyal Weizman & Emily Dische-Becker on Granta

Poetry in the face of history: Keep counting by Sharif S Elmusa on MadaMasr

Gli equilibrismi della cultura decoloniale di Carola Spadoni su Il Manifesto

Comparison is the way we know the world: Masha Gessen’s speech at the ceremony of the Hannah Arendt Prize in Bremen on Zeit.de

Palestine and Our University by Sumayya Kassamali on SocialTextOnline

How womenandchildrenandqueers and the Palestinian male monster-terrorist are deployed to justify genocide by Nisrine Chaer on Untoldmag

Notes on Craft: Writing in the Hour of Genocide by Fargo Nissim Tbakhi on Protean

Palestine’s Martyrdom Upends the World of Law by Bassem Saad on Protean

Can We Talk About Palestine? On Speech by Bishnupriya Ghosh on Jadaliyya

ICJ case ‘opens new era between the Global North and South,’ says UN expert by Alba Nabulsion +972mag

On Mourning as a Motive Force: Grief and Black-Palestinian Solidarity by Malkia Devich-Cyril on Narrative Initiative

Revolution For Kids—Dar El Fata El Arabi, Recollected on Bidoun

The Destruction of Palestine Is the Destruction of the Earth by Andreas Malm on Verso

The Principle of Return: The repressed ruptures of Zionist time by Adam Hajyahia on Parapraxis

“Anatomia di un genocidio”. Il rapporto di Francesca Albanese sulla situazione dei diritti umani a Gaza di Rafaëlle Maison on OrientXXI

What it’s like to be the only Palestinian journalist in the briefing room on TRTworld

“Zionism Über Alles” by Hans Kundnani on Dissent Magazine

Germania, a che punto è il silenzio di Carola Spadoni su Il Manifesto

Da Israele a Berlino, la voce di Iris Hefets di Carola Spadoni su Il Manifesto

My Existence in My Homeland is Resistance by Heba Dbaa on No Niin

You can kill the flowers but you cannot stop the Spring: Israel’s role in the Mayan Genocide by Sara el-Solh and Paola De La Cruz on Shado

As Journalists Are Murdered in Gaza Their Counterparts Lose Jobs in America by Steven W. Thrasher on Lithub

A World Without Palestinians by Devin Atallah and Sarah Ihmoud on The Massachusetts Review

Music and resistance after October 7 by Benai Blend on Mondoweiss

The obliteration of Gaza’s multi-civilizational treasures by Ibtisam Mahdi on +972mag

‘Ghassa,’ The Lump in One’s Throat Blocking Tears and Speech by Sarah Ihmoud on palestine-studies.org

Israel’s War on Gaza Is Also a War on History, Education, and Children by Jesse Hagopian on rethinkingschools.org

Letter to Columbia President Minouche Shafik by Robin D. G. Kelley on The Boston Review

Social Hell by Nadia Bou Ali on Parapraxis

To Know What They Know by Yasmin El-Rifae on Parapraxis

The Pendulum Swing of Black Liberation by Bedour Alagraa on Roar Mag

Standing with the Palestinian resistance: A response to Matan Kaminer by Andreas Malm on Verso

The question of Hamas and the Left by Abdaljawad Omar on Mondoweiss

Berlino, la stagione della repressione e la ragion di stato di Carola Spadoni su Il Manifesto

Tirdad Zolghadr le porte chiuse di Berlino di Carola Spadoni su Il Manifesto

The Principle of Return by Adam Hajyahia on Parapraxis

The Campus Does Not Exist by Samuel P. Catlin on Parapraxis

Dehumanization by Deification by Zoé Samudzi on Verso

A Year of War Without End by Lina Mounzer on The Markaz Review

Susan Abulhawa’s remarks at the Oxford Union Debate

There Will Be No Innocents Amongst Us by Maya Zebdawi and Zuhour Mahmoud on Kohl Journal

Mohammed El-Kurd and Raeda Taha on Palestinian identity, martyrdom, and revolutionary honesty on Mondoweiss

Persecution Terminable and Interminable by David Markus on Parapraxis

Elements of Anti-Semitism by Jake Romm on Parapraxis

An In-Humanist Analysis of Contemporary Palestine by Donatella Della Ratta on Institute of Network Cultures

Palestinian liberation does not need Western approval by Mjriam Abu Samra on The New Arab

Stolen By a Map: The Haunting History of Lebanon’s Lost Villages by Dana Hourany on The Public Source

Guided by Our Moral Compass and the Fall of Forever by Livia Bergmeijer on Medium

The Conditions for Inner Exile by Emily Dische-Becker and Julia Bosson on The Diasporist

Searching for Palestine in Beirut by Sumayya Kassamali on The Public Source

S come Silenzio di Maddalena Fragnito su Effimera

“No Other Land” for Whom? by Mary Turfah on Mubi

Slumlord Empire by Alberto Toscano and Brenna Bhandar on Protean

Can Genocide Studies Survive a Genocide in Gaza? by Mari Cohen on Jewish Currents

Letter from Columbia student Ranjani Srinivasan after fleeing the United States to Canada on Norman G. Finkelstein’s website

The Ban – Opticon in the Schengen Area by Charlotte Lebbe on onlineopen.org

Germany Turns to US Playbook: Deportations Target Gaza War Protesters by Hanno Hauenstein on The Intercept

Inside the Narrative War: Mohammed el-Kurd’s “Plea Against Pleas” by Tracy J. Jawad on The Public Source

Why I’m no longer “anti-violence” – Part 1 on Tania Shoukair’s Substack

On 21 April, Germany will deport me – an EU citizen convicted of no crime – for standing with Palestine by Kasia Wlaszczyk on The Guardian

Why I don’t cheer for Israel’s ‘pro-democracy’ movement by Neve Gordon on Aljazeera

The New McCarthyism Was Started by Liberals by Jeet Heer on The Nation

On Parallel Time by Walid Daqqa on Mizna

Queering Hamas: A Colonial Weapon by Musa Shadeedi on No Niin

To my newborn son: I am absent not out of apathy, but conviction by Mahmoud Khalil on The Guardian

Gaza Genocide, German Cultural Politics and the Inadequacy of Form: An Interview with Jumana Manna by T J Demos on Third Text

Mourning as resistance: Israel’s necropolitics from Palestine to Lebanon by Dalia Ismail on OrientXXI

A Critical Look at Normalization by Dalia Ismail on Aljumhuriya

Extermination as negotiation: Understanding Israel’s strategy in Gaza by Abdaljawad Omar on Mondoweiss

‘We promise each other liberation’: Columbia activists honor expelled students at the ‘People’s Graduation’ by Columbia University Apartheid Divest Coalition on Mondoweiss

Shifting Paradigms: From Eurocentrism to Intellectual Autonomy by Mohamad Chehab on Kahf Magazine

Hunger That Defeats Language by Husam Maarouf on Arab Lit

The ‘chaos’ of aid distribution in Gaza is not a system failure. The system is designed to fail. by Abdaljawad Omar on Mondoweiss

Gaza: How power ends atrocities on its own terms by Dalia Ismail on Maktoob Media

When the ‘civilised world’ allows inhumanity to thrive, we are all in deep trouble by Ibrahim Hewitt on MEMO

Israel’s greatest threat isn’t Iran or Hamas, but its own hubris By Orly Noy on +972 Magazine

Is the US-Israel war on the Middle East and Iran a crusade? with Roy Casagranda on Middle East Eye

Axes of Resistance by Séamus Malekafzali on Parapraxis

Zionism is the root of violence from Palestine to Iran by Rameen Javadian on Mondoweiss

Culmination by Eskandar Sadeghi-Boroujerdi on New Left Review

EN

@mohammedelkurd

@nouraerekat

@radioalhara

@eye.on.palestine

@middleeasteye

@democracynow

@novaramedia

@wizard_bisan1

@workersinpalestine

@motaz_azaiza

@hiddenpalestine

@mariambarghouti

@aljazeeraenglish

@savesheikhjarrahnow

@mondoweiss

@propagandavstruth

@palestine.academy

@saulwilliams

@greg.j.stoker

@key48return

@hindkhodary

@zeteonews

@eye.on.llebanon

@vizualizing_palestine

@havenforartists

@aatma.aatma

@cartographyofdarkness

@wawog_now

@angalliance

@trtworld

@megaphonenews

@bsd.movement

@elsclegal

@alex_shams

@feminists4jina

@oma.hamad7

IT

@dinamopress

@valerionicolosi

@leila.belmoh

@randa_ghazy

@giovanipalestinesi.it

@karem_from_haifa

@chrelia

@marcomagnano

@lindipendente.online

@infosubmarine

@romanarubeo

This doc is meant to be updated with the incoming contributions and new references. We would like to thank Madu and Sandra Cane for the work they did on the syllabus, Golrokh Nafisi for the banner illustration, and everyone who’s resisting and countering narratives.

The White Eraser

This pain will not be for nothing, you said

“In one minute the entire life of a house is ended. The house as casualty is also mass murder, even if it is empty of its inhabitants. A mass grave of raw materials intended to build a structure with meaning, or a poem with no importance in time of war.” (Mahmoud Darwish, The house as casualty in A River Dies of Thirst, 2009)

Breathing the vast dimension and scale of oppression, while flesh cries out for life in days of unbearable violence. The body rejects the present. It is not about the current conditions, but the threatening absence of alternatives to them: the imposed deaths and the furious dominion of power in the silent complicity of the surroundings. Words remain empty, devoid of meaning in front of the pain of inevitability. They crash into the depth of violence, forced into margins that are too narrow and oppressive. The responsibility of death flares up in me along images of unspeakable sufferings, while life seems an exasperated shadow of a world that burns out.

Nothing will be as before, ‘cause there’s no coming back from the trauma inflicted on an entire people. We are not allowed to stop watching the land bleeding innocent souls, we are not allowed to stop praying for Palestine, we are not allowed to turn away our faces from the massacre, ‘cause we are responsible for every single death imposed by us. Today, we are not allowed to find a place for relief and comfort in the wake of obscene and perpetual violence, in front of the denial of liberation and justice, in front of the denial of Palestinian humanity. No words can bring these lives back. No words can be spoken about the counting deaths.

How can we love each other in the midst of devastation?

I wrote to you at night that my love and pain are with you.

This pain will not be for nothing, you said.

Out of this immediate realm of death, you belong to freedom.

In the uncharted territory of time, hope draws a map.

As the poet Sarona Abuaker wrote:

“we are

stretching

beyond

their wildest dreams”

You carve out a path through burdens imposed by others,

by the colonizers, by the exhausting rhythm of death.

Your words assemble a fragile body

from the shattering rubbles of oppression.

This pain will not be for nothing, you said,

bringing life again in the current numbness.

How many ways to resist beyond comprehension?

Beyond political violence? Beyond nauseating despair?

We will be free, you said,

Palestine will be free, and my love is with you, Dina.

Everlasting Waters

–

Oggi sarà il tredicesimo giorno

Lo so

oggi è per niente

come tutti i giorni

Che neanche se fosse ancora il 1948

noi siamo la sirena che non smette

ma di cantare

non ne porta più il peso

neanche tuo padre

mio padre

che mai più sa

chi sono io e perché l’ha fatto

la vita l’amore

e la morte

che riluttante

s’appende ai nostri piedi

Ancora corriamo

dobbiamo ancora cominciarla questa pace

ricordo scontato

di un colore che non è più

s’andrà ad allestire l’arte dei nostri giorni

malconcia e mai sofferente

corpi di niente che non sanno di niente

come tutti i giorni che non resto in pace

che non voglio più sentire le sirene

che non posso più ascoltare

le tue parole che non sanno di lotta

come una madre che non sa prendersi cura delle cose

vorrei essere abolita

le compagne parlano di tenera aggressività

io non sento questo caldo lamento

vedo

che non c’è empatia

non che io la richieda

la capisca l’abbia mai imparata.

non imparo mai niente

questo mi è stato detto sempre detto

sempre sempre sempre.

Fresh as Gilgamesh they said,

a silly one though, what if Gilgamesh were just incapable.

I wonder whether I was when the water came for the first time

at your feet

il sole ci sta lasciando

con lui vanno via le buone cose

le ciliegie che non mi sono mai piaciute

il sale da succhiarti tra i capelli

le ore

poche e stanche

che ci soffermiamo

per guardare un angolo

facciamo finta che sia ancora la nostra vita

qualcuno sa che è già finita

vivo questa luce primitiva che per prima mi ha bagnata e quindi accolta

un sudore battesimale ritorna

niente è stato più confuso e vero

queste acque sempiterne sono piene di noi

Tubi neri

Rocce, fiori.

Tubi neri.

Serpe, sentiero.

Tubo nero.

Mai in vita avevo

dovuto prestare

tanta attenzione a non calpestare

qualcosa.

Entriamo nella serra.

Qui che è religione e sopravvivenza

Pestare un tubo è un fatto totale.

Rasheed guarda a terra.

Ma si capisce, questo è un altro sole

Che con un raggio nutre

E con l’altro asseta

E la vita lontana prova a scassinare l’eternità con grimaldelli di vento.

Da qualche parte in questo deserto

c’è una pietra chiamata attimo.

In cui Rasheed si è perso.

Quando stacca l’erbacce dalle piante di ceci

Rasheed tiene la base ferma, impreca e guarda a terra.

Quando un pomeriggio inchioda col pick-up e spegne la radio, toglie le mani dal volante per sentire il vento tra le spighe dei campi, portiera aperta,

Rasheed gode e guarda a terra.

Arriviamo oltre il colle fra resti di un villaggio raso al suolo dove un tempo viveva la sua famiglia e ora c’è lui solo. Rasheed ricorda le storie, prende a calci le macerie poi si ferma e guarda a terra.

Il resto della sua giornata

È di un indicibile solitudine.

Lo vedo mangiare da solo,

Dormire da solo,

Lavarsi da solo di fronte al nulla.

Che sta bene così. Che sembra potrebbe sopravvivere al mondo.

Di santo silenzio contadino.

Lui sa di essere nato per questo.

Nel ripetersi diventa eterno e l’eterno porta consegne ardimentose oltre ogni calendario.

Lo fisso nella sua impenetrabile intimità contadina

Spezzata da una sigaretta.

Ogni giorno il suo desiderio si fa una tana dove morire.

Al riparo da tutti gli inverni che il letargo dell’abitudine deposita.

Mentre lo aiuto a riparare i tubi con cui ruba l’acqua per coltivare le zucchine o come la chiama lui “agroresistance”.

Rasheed tiene in bocca una torcia e so già dove guarda.

Perché quella terra gliela stanno portando via.

Rasheed è un contadino palestinese della periferia di Bardala costretto a rubare la sua stessa acqua all’esercito israeliano che la estrae illegalmente.

Lui combatte così. Riprendendosi l’acqua, rischiando la vita per coltivare zucchine.

Volontaria azione, involontaria pulsione. A volte resistenza è solo provare a vivere come le altre persone. Fare finta sia normale.

Come il fiore si ostina a crescere nell’asfalto,

Rasheed coltiva zucchine nel deserto.

A fine giornata, quando piovono a cascata i canti dei muezzin e i cani corrono in branchi sui tetti a sentirli, dà da mangiare a cani e cavalli, mette a letto le bimbe nella giacca di montone e scoppia a piangere in silenzio; i suoi zigomi sono versanti di colli difesi dall’orgoglio mentre si stende sul pavimento della sua fattoria da solo, avvolto in una coperta. Ma non guarda più a terra. Adesso guarda il cielo. E so, perchè l’ho visto, che gli dà la forza di continuare a ripetere qualcosa di incomprensibile, ma giusto. Come il moto delle stelle. Non lo sapremo, non lo saprete mai. Rasheed vive. Continuerà a combattere nonostante tutto il mondo intorno.

Feet

Academy

Approximately ten thousand lives

in thirty days: there

I said the number, bracketed the life

for your (lack of) imagination. Sorry,

I have to speak your language; the numbers,

denizens of the rational world,

are concrete. They cannot dictate

cannot direct, cannot bring back,

or unfold

what you have pleated into time.

The archives confirm: there is a way to knowing

and telling what you know: your eyes.

What you have a beginning and an end to,

what your digits have use for,

what is signified and assigned.

The Academy might not know

the truth, rehearsing

vocabulary for a living

but hey, let me give you another number:

the Crusader landed only 75 years ago.

There is nothing holy about his promise;

the gambler only chose his king of spades.

So don’t talk to me

about memory culture, if you don’t know

how to remember.

Words

I have been thinking about words in these last weeks, maybe more than I ever did.

We—the ones safe in the distance of privilege—have been doing a lot of sharing of those lately. We have been weighing the words of others, as well as the images we chose to share or withhold, the narratives we constructed as individuals, communities, and institutions. Some sought refuge in silence, while others found guilt in it. Some crafted sentences to find sleepy comfort in them, avoiding a call to action.

It was a month yesterday.

I received a DM from someone I fell into an online argument with some weeks back. I disagreed with their use of words and images, as I felt they were eluding, or plastering over, the facts.

The fact of dispossession.

The fact of displacement.

The fact of apartheid.

The fact of collective punishment.

The fact of war crimes.

The fact of genocide.

The conversation got twisted, it moved in circles. Discussing about wording when people are retrieving the remains of loved ones from collapsed buildings, which once were homes and schools and hospitals. Discussing about wording though, when, this side of the screen, this side of the world, this side of the “art world”, words is all we have.

I got a message to reignite a conversation on lexicons and responsibility, one month after it was cut short by an impossibility of shared understanding.

I got a message about words and wording, after 10,022 deaths, and counting, and counting.

The message linked to a video. A video of a well-meaning white European addressing a room of well-meaning white Europeans. In the video a song, whose lyrics invites the audience to find other audiences, and to speak to them about Gaza, about Palestine and Palestinians. However, remember, the song adds, to be steady in the knowledge that you/us have no right to be angry. And the words you’ll use to recount that foreign pain—which is not for you to hold—to others, make them adaptable to stranger ears. Use words that are familiar to them, have them understand, aim at the largest reach. Try to find alliances even in the most desperate of places, make them aware, so that they make them stop.

I have been thinking about words in the last days. More than anything I’ve been listening and reading the words of others. The words of those on the front line, those who are still speaking while standing beneath that falling sky. I too, like the well-meaning person in the video, have wondered whether my own words still held any meaning. I too have considered whether my presence mattered at all. I too have pondered whether I had a right for rage.

They did not, it did not, I had not.

And yet, I believe, I still believe as I still can see, we, who are far from that falling sky, we can be a body on the street, screaming to be heard. We can be a voice in here, writing to be read. We can, still. As we are, still.

And still, I am enraged.

One month has passed. Many conversations were topped by an equal number of silences. Many words will never be spoken again. And now, and always, and forever, you’ll close your eyes, and you’ll see Gaza closing her many eyes. One by one. The rubbles and the noise, the loss, the loss, the infinite loss.

10,569 and counting, and still counting.

Make the abstraction of numbers cut through your tongue. Try to wrap each figure with the complexities of language. Remember names you never knew. Call for them. Let unfamiliar sounds compose something of a recognisable identity until you catch in cold figures the glimpse of a familiar face, the gaze of someone you loved.

And then speak, since you can, as loud as you can, as angrily as you wish. Speak the same words you’d utter if those closing right now were eyes you once cherished.

Demand.

This is a task for today, and an endeavour for all days to come.

Until freedom.

From the river to the sea.