Decolonize!

Cultural practices and events are an occasion to reflect on the space they come to occupy and inhabit—even if temporarily. As it is often the case in Rome, the architecture becomes an overwhelming element to deal with. This year the new location granted by the Region to the performative art festival Short Theatre was the rationalist building of the ExGil—literally former Fascist Youth. After its restoration and reopening the space was renamed as WeGil by the Regione Lazio administration, and is currently used as polyvalent cultural space and venue for exhibitions, arts and culture. Luigi Moretti’s building was inaugurated in 1937, as the space for the fascist organization Gioventù Italiana del Littorio, and used as such until the end of WWII. This cohabitation couldn’t but trigger a reflection about the building itself and the city at large, their symbols and history. The artistic production of today has the power—and duty—of reshaping and resignifying the matter of collective memory, through its contemporary theories, influences and gestures. Indeed, the considerations that came about necessarily tackled the colonial fascist past of Italian history and geography inasmuch as their tendency to remain incomplete, often laboriously countered by feminist decolonial artistic and educational practices.

This issue unfolds through the words and personal experience of writer and journalist Igiaba Scego, who in her piece For WeGil takes Rome as an emblematic case of historical indifference; followed by researcher and curator Simone Frangi’s The Crime of Innocence, a focus on “harmless” monumentality and neocolonial continuum; through their collective intervention (We) are not Gil, Ilenia Caleo, Isabella Pinto, Federica Giardini and Serena Fiorletta attempt to “complete” the historical traces embedded in the ExGil building; the continuous work done at the Master in Gender politics and studies, especially around its Arts Module, as witnessed and recounted by Paola Granato in Entanglements; and it overall attempts to follow the traces of a decolonial feminism, as put in practice by the collective Décolonizer les Arts (active in Paris since 2015) and theorized by Françoise Vergès, here interviewed by Giulia Crispiani. Special thanks to Short Theatre for making the effort and not remaining indifferent.

The contributions by Igiaba Scego and Simone Frangi and the intervention by Ilenia Caleo, Federica Giardini, Serena Fiorella and Isabella Pinto were commissioned by Short Theatre.

For WeGil

Igiaba Scego

Rome is a fascist city. To some democratic ears this sentence might sound as a blasphemy, and probably it is. Yet, there’s some truth behind; if we ought to be tied to historical pragmatism, we can’t neglect the fact that inside Rome’s thousand (hi)stories there is also the history of fascism. When I think about Rome, the city where I was born and raised, I always imagine her as a multilayered cake, as those you’d find at a wedding. Layers in support of other layers, and so on to infinitude. Layers of cream, chocolate, pine nuts, currants, pastry. Layers. Rome has kept all these layers very well preserved. It’s easy to see beside the vestiges of the Augustine and Trajan imperial Rome, the remains of the three hundred towers that dominated the city skyline during the middle ages. Beside the pompous slightly-arrogant Baroque Rome of Bernini and Borromini, we find the shy Rome of the Renaissance. Michelangelo was in Rome and he’s still overlooking the city with his cupolas, alongside his eternal enemy Raphael, the men who gave a charming touch to the women of the Urbe, turning them into emblems of eternal beauty. The mad genius of Caravaggio duetted here with those who ended up imitating him. Trained in a her dad’s workshop in Piazza del Popolo, Artemisia Gentileschi was the courageous woman that went against the trend of the time that forbade art to women, and forbade women to denounce their rapist.

Edward Lear, Temple of Venus and Rome, 1840.

After, the seventeenth and eighteenth Century Rome. The roman countryside that inspired the imaginary of foreigner travelers, from Goethe to James. But then, since 1870 with the annexation to the Italian kingdom, a new Rome is pawing to come to the surface. It is no coincidence, this new Rome is born from a flood that almost drowns her. As the river in flood, transformation can’t be contained, and with the 1873 masterplan Rome suddenly begins to change. A train station, wider roads, and everything the travelers were considering picturesque is slowly vanishing. Yet Rome is a city of ghosts, and nothing truly disappears, but rather hides, melts, finds a shelter to resist the passing of time. The same happened to the Rome of fascism. We have the tendency not to see it, we pass by ignoring this fact. We tend not to see the lictiorian fasces on the sewers of our rundown neighborhoods, as we don’t see the fierce eagles laying on those vertical axes and those Roman numbers indicating the fascists epoch; as if it all became transparent. These traces of a Rome that believed to be an empire again, Mussolini’s empire, are all around us. Yet, in the majority of cases we seem to be indifferent, the inhabitants don’t seem to even notice these evidences. I immediately had to realize that if the Colosseum is part of the identitary texture of the city, the rest—especially when linked to fascism, seem not to be even taken into account. I’ve never managed myself to be indifferent towards this colonial fascist Rome.

Of Somalian origins, I was born in Rome from someone who had directly (my father) and indirectly (my mother) experienced this colonialism, and I could never ignore this Rome that was sending me back to this in-between history, between Italy and Africa. Somalia and Italy have been tied by a not so long yet intense colonial history. Italy used Somalian civilians to conquer Ethiopia, and Somalian cities are to a certain extend a copy of Italian seaside towns. Moreover, Fascism has left behind a ticking bomb that left marks throughout Somalians’ bodies. Beside wars, abuses, apartheid imposed on Somalians by Italians (same happened in the other colonies), the worst weapon was ignorance, meaning to have denied the right to education to the Somalian people. Somalians and generally speaking colonial subjects could not attend school beyond 4th grade. Even after the historical colonialism, Italy and Somalia were tied for ten more years by the so-called Trust Territory of Somaliland (Amministrazione Fiduciaria italiana – AFIS). For 10 years the ex colonizer was meant to “teach democracy” to the ex colony. An absurdity imposed on Somalia by the United Nation (thus the rest of the world) the Somalian people are still paying the consequences for. How can the ferocious dominator possibly “teach you democracy”? What kind of democracy are we even talking about? Democracy stems naturally from the people, through processes and waitings, surely not by imposing the Western nation-state matrix.

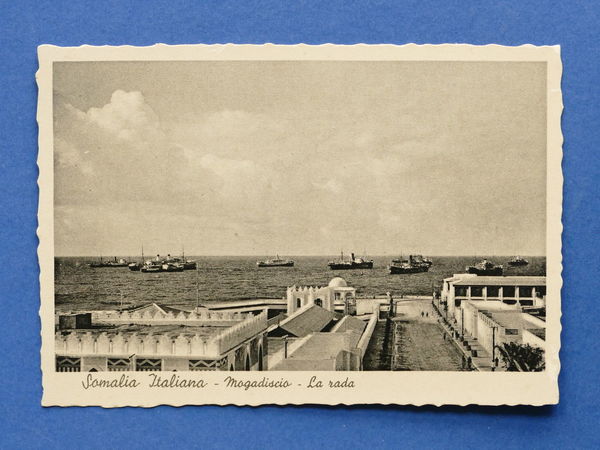

Postcard Somalia Italiana, Mogadishu.

Back then, the idea was that the whole world had to resemble and be like the West, and that was it. With no chance for negotiation. The fascist Rome I crossed as a child and as a teenager was triggering urgent matters, regarding my own life directly. Regarding the reason why my parents’ Somalian documents (before they’d get Italian citizenship) were written in Italian, and why Italian 60s singers were really popular in Somalia, and why in Mogadishu movies were dubbed in Italian. The first time I went to Somalia I was eight years old and I immediately had the feeling to be in Rimini, although some parts of the city where more similar to Naples. Mogadishu was a mixture of its conquerers’ styles, from Portuguese to Turkish, via Arabs and Italians. I was always very struck by the arch of triumph, with the inscription “Umberto Romanamente” built for a Mussolini who never came; I always had this impression the monument was nothing but a bad copy of the Constantine arch, the one next to the Colosseum. Since Mogadishu was also forged by fascism, I’ve always found both cities very similar. Yet, my reflection on a professional level on this fascist and colonial Rome came quite late, when I was already over thirty. Before I was simply crossing that Rome, as she lived upon me, giving me some concerns and nothing more. Then this Rome became something more than my city of birth. I was hanging on Rome as the only thing left to grasp. She was not simply the place were I grew up, but her fascist sides were also reminding me of Mogadishu…and that Mogadishu was completely destroyed by 1991 civil war—a war that never really ended, as today’s weak peace is built on terror attacks and massacres. The Mogadishu of today is another city, built on the previous one’s wreckage. A city I lost all contacts with. From time to time I find that Mogadishu in Rome, in those colonial traces common in both places.

Now I might sound nostalgic towards fascistic vestiges, and it must be firmly stated, I am not. Yet it is important to understand where I come from to (re)read what each citizen and tourist finds in Rome every day. Since the beginning I’ve realized that only few of us can recognize these signs. Memories of this brutal colonial history, not only fascist but also of the XIX Century, were swarming the city. The square in front of Termini train station is called Piazza dei Cinquecento (Square of the five hundred), recalling the lost battle of Dogali, in Eastern Africa, in the 1800’s. When you think about it, colonialist and fascist references seem to burst through the city. From Piazza S.Augusto Imperatore in Eur, to Ponte Duca d’Aosta to the school in via Palestro dedicated to the Duca degli Abruzzi and built as a military ship with portholes. Rome wasn’t really hiding anything. I only had to look and decode. But was it always as such? Clearly not.

Foro Italico in Rome aerial view.

After WWII, Italians were very aware of the urban space surrounding them. Many reflected upon these traces, tried to find solutions, raise awareness and understand what to do with this uncomfortable past weighting over everyone’s shoulders. Immediately all the attention was focused on the Foro Italico. Today people go there to see AS Roma and Lazio’s soccer matches. Young kids are skating, and the mosaics glorifying fascism are falling apart. Some pieces are missing, ended up under some rolling blade or smashed by the flow of the thousands of hooligans going there to shout “Forza Roma, Forza Lazio.” Then the graffiti, there the paradox lies. Often neofascist messages, such as “Boia chi molla” or “Negri nei forni” (literally “death to those who surrender” and “niggers to the ovens”), defacing the same fascist mosaics and the very fascism they are inspired by. Post-modern shortcuts. In that same Foro Italico dedicated to sports (beside the stadium is the swimming temple) there is the obelisk of contention, the one shouting “Mussolini Dux”—an inscription that has righteously caused political controversies, since right after the war. An important year (although the year of a missed chance for change) in this sense has been 1960, the year of the Olympic Games in Rome, when the Ethiopian Abebe Bikila won the marathon also to avenge the failure of the restitution of the Axum obelisk to Ethiopia; the Olympic Games of a 18 years old Mohamed Ali and of the commentator Jesse Owens. A triumph for Rome, as one of the most beautiful editions.

What’s left unknown about those Olympic Games is all that concerned the Foro Italico before that dream games. Italy needed those games in order to show its new face to the world, as the world remembered that Italy had just fought beside Hitler, and despite the partisan war, its fascist past. So for being so blatantly fascist, the Foro Italico was quite an issue. What to do? How to welcome athletes from all over the world to those mosaics calling for the world’s destruction?

Eventually, only a fast restoration was done, it was decided a fast cleaning job would do, with the abrasion of some of the mosaics’ texts and some sort of cancellation on one of the marble slabs on the avenue’s sides. Basically it was decided to get rid of the most offensive sentences, related to the Genevan sanctions that followed the invasion of Ethiopia and the fascist oath. The obelisk and the mosaics dedicated to the empire in Africa and the fascist squads remained untouched, with their sets of “Me ne frego” (I don’t care) coming along. In this regards, Maria Antoniera Macciocchi said in an article titled La funebre truccatura fascista (The funerary fascist make up) on the pages of Vite Nuove: “If the government has the duty of hospitality towards the foreigner athletes, then it has an even more urgent duty towards us indigenous, habitual guests who find the grotesque gaudiness of the regime as indigestible and even more deleterious towards the new generations, than towards the Soviet, American or Swedish visitors. The ‘writings on the wall dictated by the dux’ represent in fact the remains of a slobbish habit where the martial roman ‘hard’ style of the ventennio (the twenty years of regime) is entangled to the peasantry of the country at large. Indeed, it’s about a conception of life that the leftover fascists are defending precisely because it’s as such, that we want to cancel for opposite reasons: this deforming mirror of Mussolini’s mottos, in which the caricature of the Italy of the ventennio shows up, is offensive and falsified and deforms the democratic history of today.”

ExGil, Rome.

That’s how the Foro Italico became a bone of contention. Macciocchi continues: “The problem beside the Olympic Games is to strip Italy bare of this fascist outfit, everywhere, this macabre makeup that is defacing its features. Let’s pose this problem to the Consiglio Nazionale della Resistenza (resistance national council); let’s point it out for our deputies to push the government to take a position on this issue, as they have already done with the Foro Italico’s inscriptions. Meanwhile, from this week Vite Nuove opens an extraordinary reportage, written by our readers themselves: what are the signs of the regime’s apologia defacing our cities and country? Send us photos and every week we will publish them on these pages, until we’ll have a proper documentation, a complete dossier that will force the new Fanfani’s government—rising on antifascist premises—to respect the laws against fascism’s apologia and to issue an order of cancelation. It is not a caprice to want this putrid fascist rouge to disappear, but it’s meant to teach to the new generations another page of the tragic fascist masquerade, and to reaffirm that our governing ideals are stemmed from resistance and antifascism.”

Maria Antonierra Macciocchi’s words are still resounding and force us to face these vestiges that were neither canceled nor abraded. In comparison to 1960, these traces are immersed in oblivion, while in the city fascism has raised its head again. So today it is even more urgent than yesterday to understand what to do with this uncomfortable urban legacy. Indeed, probably destruction is no longer formally possible. Those monuments, those dark remains have still become historical traces year after year. How can we conserve them without being contaminated by the fascism they emanate?

One of the most interesting examples in this sense is the space of ex Gioventù del Littorio (Lictorian Youth), today WEGIL. The rationalist forms of the Trastevere’s building have merged with a veneer of modernity, more towards conservation than destruction. Nonetheless the space remains charged with a negative energy we must face, in order to deconstruct and decolonize it. Spaces like WEGIL are challenging us. What to do with the fascism of the past and how to prevent historical palaces to become emblems of contemporary evil like racism, sexism and homophobia? How do we bust the ghosts out of the building? Here the 60s debate comes in handy again, that debate before those olympic games that should have carried Italy into modernity, around the Foro Italico mosaic texts. One solution comes from an unexpected pen, that of Gianni Rodari. Mostly known for his children literature, he in fact started his career as a journalist with a significantly polemic attitude. In one of his articles dated 7 November 1959 and titled Poscritto per il Foro (Post-scriptum on the Forum) Gianni Rodari writes something that can still be useful today, for us to unbundle the intricate relationship with our fascist past: “Do we want to keep Mussolini’s words? Alright, then let’s complete them adequately. There’s enough space on the white marble of the Foro Italico. We have good writers to dictate the continuation of those epigraphs, and skilled craftsmen to engrave them. The government should appoint an ad hoc committee. They’d just need pen and paper. Necessary time for the committee’s job: one hour maybe half, because it’s enough for an Italian of average culture and honest sentiment, even if illiterate, to make this work perfectly without having to edit a comma from the current inscriptions (…) honestly we should quote the gestures of the fascists, the arsons to the Case del Popolo (peoples’ houses), the armed aggressions, the systemic violence of those teddy boys, way more repugnant than their contemporaries, that the squads were; but it doesn’t seem legit to forget that the fascist membership was equal to the food stamps and the working permit; neither would be unfair to remember that, when the dux fell, no one of those fighting squads moved a finger on his defense, and finally, to say things for what they actually are, we should write that neither the fascist squads nor the Opera Balilla nor the GIL (both sections of the fascist youth) managed to corrupt the Italian youth, if it is true as it is true that afterwards especially young people went fighting against fascism, despite their fascist education. (…) Point by point, the update of the Foro Italico’s statements would allow the creation of a contemporary history museum, where students could be taken to study, walking and breathing Monte Mario’s fresh air.”

MK, Bermudas forever for Short Theatre at WeGil. Photo Alessandra Cardinale.

Gianni Rodari shows us a way. To fill in the unsaid, to complete. By carrying their load of a difficult past, the monuments are showing us only a side of history, the side of the dominators, and it’s up to us, as Gianni Rodari suggests, to add the history of those who were dominated, even by adding how the dominators have depleted people’s rights. Not just their glory then, but their misery too. Not just their lies, but the reality of a complex Italy. Those traces must be filled with meaning, especially in the case of spaces like the WEGIL. The evil and pain that fascism has caused to the world are still covering those walls, embedded in for instance the map of Africa inside the building. Then those walls must be filled with the history of the victims, they must be filled with a no longer monochrome history, but a decolonized history made of unconciliatory content towards the history which that architecture was meant to narrate. Each wall must be filled with meaning against sexism, racism and homophobia. Those who will inhabit the space, whether audience or performers, should be pushed to mingle and mix with the others, to become more and more creole. For a very long time Italy perceived itself as a white country, when instead (and this is its fortune) it is a Mediterranean country, a fact made even more clear by recent migrations. It is precisely this mixture that must be taken inside the fascist traces of the past. These traces must be unfolded and subverted.

By the end of his article Gianni Rodari writes: “Just to give a final touch to the oeuvre, we could commission a monument to a sculptor, portraying Mussolini escaping disguised as a German soldier; that would be the first example of ‘negative monument’ beside way too many monuments celebrating illustrious mediocrity; a monument for a fearful man who didn’t have the courage to face judgment, to take his responsibilities, or to kill himself as his nazi homie.” Gianni Rodari’s words might seem harsh, yet they show us a way through a very heavy history; alongside pedagogy (by filling in the holes of history, to add what has never been told to what there is: indeed to complete), demystification is always necessary. Only as such we can actually deconstruct something, the fascism the country hasn’t properly dealt with yet.

The Crime of Innocence

Simone Frangi

“The postcolonial is a desire, the anticolonial is a struggle, the decolonial is an obnoxious fashionable neologism” Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui

In October 1935, while Mussolini launches the abusive military campaign of Ethiopia’s invasion, with no official war declaration, in a remote farm on the Norwegian coast, with no water nor electricity, the artist Hannah Ryggen starts to weave her first antifascist tapestry in lucid political anger. The piece initiates an insisting long-term process of visualization of the artist’s positioning against the crimes committed by the absolutist and colonialist dictatorships, backbones of Eurocentric modernity. Far from any empty interventionist rhetoric, Ryggen’s artwork Ethiopia is the result of a raging weaving labour conceived as a form of political resistance, able to insert anti-colonial narratives into the social imaginary. These narratives are based on the principle of violence redistribution: Mussolini is portrayed beheaded by an Ethiopian civilian, while Haile Selassie turns his back at him, replicating the indifference that international politics had reserved to Ethiopia’s violent occupation by the Italians. Ryggen’s textile painting was censored at the 1937 World Exposition in Paris. On this occasion, the section of the tapestry portraying Mussolini’s beheading was hidden—folded back into the panel—as it was considered too offensive towards the Italian hierarch, for some reason more offensive than the colonial massacre that the fascist regime was committing in Africa and in the Middle East in the same years, systematically portrayed with pride both in the homeland and in the nascent Italian empire.

Hannah Ryggen, 6 October 1942, 1943. Tapestry in wool and linen, 170 x 420 cm, Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrimuseum, Trondheim, © H. Ryggen/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2019, Photo: Ute Freia Beer/Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrimuseum, Trondheim

Ryggen’s instinctive anti-colonial drive opens up to complex and ambiguous challenges for contemporary artistic and curatorial practices. For instance, can art’s operative field—within its institutions, methods and habits—become the effective and efficient place for a (self-)critical struggle? Can art be used as a platform to deconstruct imperial narratives and practices, the voracity of which bounds them tightly to capitalism and heterosexual patriarchy? What is the role of the anticolonial commitment within artistic knowledge production in the compensation of that residual coloniality that lingers placidly on our symbols, on our representations, on our visual culture and most of all on our laws? Can artistic research take on the task of resignification and slow erosion of racism, assimilationism and contemporary cognitive and material extractive phenomena? Can it revise those social asymmetries of sexual-colonial matrix that we “inherit” in our social subconscious from a colonial history protected by strategies of organized amnesia, and that we actively reproduce in what in his article Columbus, How do I get rid of my hangover? Francisco Godoy Vega calls “colonial drunkness,” meaning that state of euphoric languor we abandon ourselves to, due to the toxicity of the very colonial substance that produces it, marking a historical continuity between present and past forms of violence?

For the entire duration of Italian colonial history, a fecund yet problematic complicity existed between colonialism, art and architecture, as well as cultural practices and creative enterprise, in the clear aim to evoke those imaginaries that were necessary to socially support the imperialist project in the homeland. Institutions such as the Triennale in Milan—which in 1940 commissioned architect Carlo Enrico Rava to initiate a project on a “new history of colonial design,” the prototypes of which were shown in the controversial “Mostra dell’attrezzatura coloniale” (Colonial Equipment Exhibition)—and the Mostra Triennale della Terre Italiane d’Oltremare (Triennial Exhibition of the Italian Lands Overseas), also inaugurated in 1940 in Naples, contributed effectively to the washing of the empire and to the construction of a proper colonial consciousness, through expositive events, commercial productions, and the circulation of either artistic or architectonical pro-empire and pro-fascist pamphlets, some of which were openly backing the positions of the Manifesto of Race (1938). On 17 May 1940, the Giornale LUCE (the first Italian mass newsreel, created and widely used by Fascism) broadcasts the opening of the Mostra D’Oltremare, portrayed through some aerial shots. The camera drifts on the features of the Torre del Partito (Party Tower), 46 meters of pure rationalism adorned by the muscly statue of the Vittoria Fascista (Fascist Victory). Few seconds after we hear the reporter’s anonymous voice defining the architectonical complex a “complete and impressive synthesis of the millennial oeuvre of civilization done by Rome and Italy in the lands overseas,” while the camera browses on the askaris “imported” in the homeland, disseminated among the buildings and displayed as military ornaments; then the Eurocentric cartographic images of the colonized Africa, alongside wall paintings, sculptures and reproductions of colonized, racialized and animalized subjects. As Peter Friedl observes in Secret Modernity, if the Italian colonial era had benefited of an apologetic support from the arts, after the fall of Fascism, were precisely the arts that “repressed and nostalgically falsified its colonial history.”

The articulated and punctual project of colonization of the imaginaries, and of colonial indoctrination mediated by cultural, artistic and architectonic forms, was associated in a pre-fascist and fascist epoch to a program of “erection” of monuments—in all its phallogocentric ambiguity—meant to represent the vision, but also for gathering and civic usage. This kind of apparently harmless, diffused monumentality worked (and keeps on working) as actual stronghold with a hidden pedagogical task, namely to allow collective identification forms through a symbolical emotional civic training, that this inoptic vision surreptitiously conveys daily. In her text L’italiano negro. La bianchezza degli italiani dall’Unità al Fascismo (The Italian Negro. Italians’ Whiteness from Unification to Fascism), Gaia Giuliani precisely underlines the function of colonialism in the symbolic and material expulsion of blackness and other ethnic affiliations, “at the other side” of the Mediterranean, from the processes of construction of Italians’ racial identity. “The metaphor of the biopolitical and emotional belonging of the fighting people to the Motherland, that consolidated during the Italian Risorgimento (Unification), WWI and in Libya, as well as the metaphor of ‘blood’ intended as a founding familiar bond of the community of Italians, set the basis for strong forms of identification within the imagined community of the nation.” Two figures over all belong innocuously to our affective patrimony, for their “naturalized” emotional proximity to the urban space we frequent. For a long time, they have embodied the purpose to bring the civic body nearer to the patriotic ideology of a fascist-colonial imprint: namely the Milite Ignoto (unknown soldier), whose monuments are dedicated to those compatriots “that had given their lives (…) for the greatness of their Italy” and Maria, his parental female counterpart, the mater dolorosa, who lost the “flesh of her flesh” in battle (to further explore this topic we suggest the performative project Milite Ignoto [2014-2015] by Italo-Eritrean artist Muna Mussie).

Muna Mussie, Milite Ignoto. Museion Bolzano, 2018. Photo Milite Ogbazghi, courtesy the artist.

What to do then with these either massive or modest yet monumental expressions, apparently weakened yet still active as actual physical presences in our existential spaces, feeding the discursive and material construction of a neocolonial continuum between the ideological North and the ideological South, clearly expressed in today’s migratory politics, racial hierarchies and structural racism European nationalisms are built upon, in the fake multicultural rhetoric of their political and cultural outsets? If it is true that, in the problematic absolutism of this conservatory mission the patrimonial logic protects the objective value linked to these monuments’ cultural heritage, the very same logic reproduces a rhetoric of innocence around the ideological indoctrination operated by the monuments, comparable to what James Baldwin describes as selfexculpatory crime. In October 2017, five years after the financing and construction of a monument in Affile dedicate to the “butcher” General Rodolfo Graziani, active in Libya and Ethiopia in colonial times (we recommend two recent audiovisual contributes: Alessandra Ferini, Negotiating Amnesia [2015] and Valerio Ciriaci, If only I were that Warrior [2015]), Ruth Ben-Ghiat publishes on the New Yorker the article Why so many Fascist monuments still standing in Italy? a provocative analysis of the persistence and “well being” of the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana (Palace of Italian civilization) in Rome, which recently became the headquarter of the luxury brand Fendi. This monument carries on its facade the sentence proclaimed by Mussolini to announce the colonial invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, that describes Italians as “a people of poets, artists, heroes, saints, thinkers, scientists, navigators, and transmigrants.” Poets, heroes and saints who committed the most atrocious war crimes in the Horn of Africa, during “just” 80 years of occupation. In his article Ben-Ghiat describes the Square Colosseum as a relic of the fascist colonial aggression, wondering why this monument, instead of being politically repudiated or culturally resignified is being simply celebrated as a modernist icon, by systematically ignoring its implication with the regime. Ben-Ghiat states that Italy, as most European colonial powers, has never submitted its colonial and fascist monuments to a re-educational program but rather simply enacted some palliative measures, such as the removal of the lictorian fasces and the Mussolini’s busts from public places, thus either validated them or relocated them in museums’ storages. For Ben-Ghiat, the void caused by both the removal and the larval presence of the colonial pride in museums’ attics and basements keeps on operating in coordination with all those monumental complexes considered minor, or less explicit abandoned to the illusion of oblivion, but will nonetheless fulfill in practice the same ideological game. The article closes by stating that “if colonial monuments are treated merely as depoliticized aesthetic objects” they allow and justify the perpetuation of the racist ideology and the settling of the radical right position as an instrument of cultural addiction.

Archivio Lapadula, Palazzo della civiltà italiana.

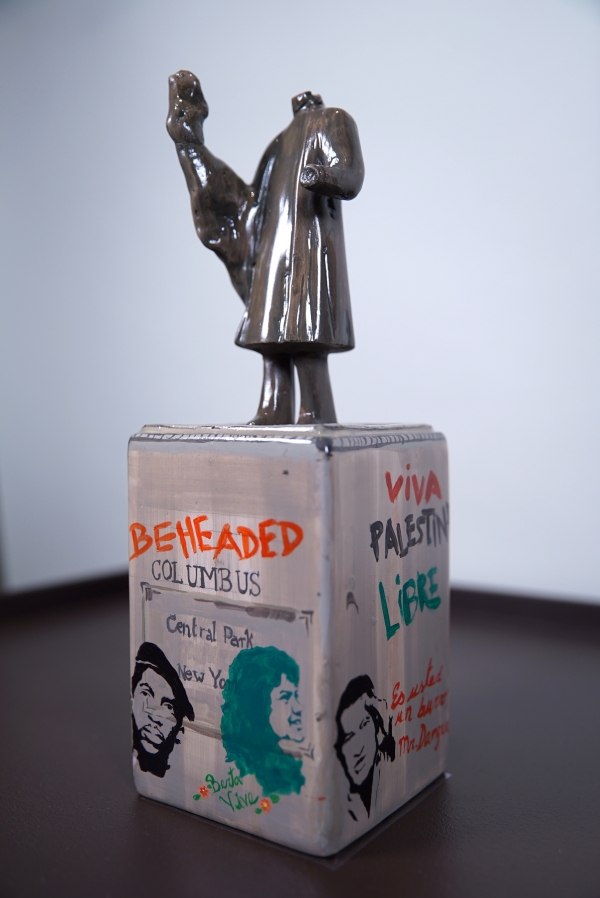

Again, in Columbus, How do I get rid of my hangover? Francisco Godoy Vega underlines the existence of “nodes at the intersection of colonial processes and exhibitions, the cultural industries, archives, migrations, and radical sexualities,” on which to intervene in a dissident manner in order to invert the negative and apologist influence of these lines of solidarity the museum is the most evident result of, as the voyeuristic place par excellence, where the instrument of display—as conceived by ethnographic praxis—helps create subaltern identities and favor the contemplation of their exoticized bodies. By following Godoy Vega’s intuition, in 2018, Peruvian artist Daniela Ortiz begins to develop the ceramics series Anti-colonial Monuments, as a consciousness device that proposes the vandalization and removal of monuments erected in diverse geographies dedicated to Christopher Columbus’ colonial fetish, followed by the substitution with anti-colonial monuments, dedicated to the celebration of historical moments during which the colonial asset was compromised or upheaved by subaltern forces, carrying within some counter-statements to the predominant colonial narration, such as “On the shoulders of the oppressor our pain will weight” or “This land will never be fertile for having given birth to colonizers.” The principle of this work is precisely the same redistribution of violence, as pedagogy for monuments, Ryggen was inspired by. Five years before, in her intervention The Culture of Coloniality, in the context of the seminar Decolonizing Museums, Daniela Ortiz was drawing a precise quadrangular relationship among historical colonialism, residual coloniality, culture and European migratory politics: either in admission processes or political asylum and integration procedures, “culture” is the first aspect to be assimilated by a migrant person seeking for permission to stay. According to Ortiz, in colonial cultural economies the museum is the place of (not just symbolical) Eurocentrism’s legitimization, sustained by the colonial mentality and by the migratory managerial infrastructure that decides which subjectivities and what cultural expressions are valid, and deserve to be disseminated in the framework of nationalistic projects. Ortiz distrusts those announced decolonizing processes of ornamental kind that do not imply profound reform in the very body of the institutions and the practices that they produce. By imagining forms of more efficient collective empowerment, Ortis implicitly suggests that, in the reality of a Europe that drifts towards a sovereign and suprematist direction, the activist impact of institutions is measured in the programmatic exiting from their presumed neutrality, and in their pragmatic alignment to the socio-political realm: “The fact that cultural institutions do not express any resistance to culture, being used to reinforce xenophobic and racial segregation practices by means of the discourse of integration, makes it impossible to imagine how a process of decolonization could take place simply through exhibitions, debates and talks that regularly appear in their programs of activities.”

Daniela Ortiz, Columbus · Colón. Description: Anticolonial monument proposal to be installed after the Christopher Columbus monument of Central Park New York built in the year 1892 is torn down.

In resonance to Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui’s statement that opens this text, and aligned to Daniela Ortiz’s intention, in the essay Post-colonial does not exist produced for the program The Night School14 directed by Marissa Lôbo and Catrin Seefranz in Wien, artist and activist Jota Mombaça is questioning precisely the authenticity of the spaces of post-colonial resignification, in particular the ones open to the arts, and on their major or minor participation to the colonial logic that they criticize:

“…self-proclaimed postcolonial spaces, or even decolonial and anticolonial ones, are not exempt from reproducing coloniality as systematic. The way in which these spaces articulate themselves, who coordinates them, who decides for them, which power relationships, what they write, how, with what support, for what circuit: all these modes of trafficking in the midst of the ruins of colonial relationships (and producing from them) mobilize—almost as a rule—a contradictory, non-negotiable dimension, the fruit of a racial historical wound inscribed tenaciously onto the social body, though much more poorly elaborated from the point of view of collective feelings and emotions […] making anticolonial conflicts vibrate—that deny at once whatever national projects that may be, extractivism and ontological terrorisms of whiteness, of patriarchy, of supremacy, and of heteronormativity, just as the imperial geopolitics and the universalism of power—is a way of opening up cracks in coloniality to let pass to the present the more-than-colonized forces.”

We are not GIL

Ilenia Caleo, Serena Fioletta, Federica Giardini, Isabella Pinto

Entering and crossing a space is never a neutral action, especially when a place has a specific identity and a historical density that can’t be ignored. When we entered the ex-GIL building, to inspect the space before the days to come (the days of the Short Theatre festival and the Master in Gender Studies and Politics) we immediately understood that we, as feminists, we couldn’t be—think, discuss, meet in there. The space had to be decolonized first. The point was not simply the debate around the survival and revival of such spaces, once fascist buildings or somehow marked by the regime; the most evident issue today is that the restoration intervention neutralizes, or to say the least remains silent on the history of a building in one of Rome’s most central neighborhoods; factually reaffirming and legitimizing the re-emersion of a present that never operated a precise choice on the Italian fascist and colonial past.

(we) are not Gil, intervention at WeGil for Short Theatre, 2019. Photo Claudia Borgia.

GIL is the acronym of Gioventù italiana del littorio (Italian Lictorian—fascist Youth), and the building was commissioned by the Opera Nazionale Balilla (another section of the Italian Fascist youth organization) in 1933. Shut in 1976, the building was reopened in 2017, following a restoration that took it back to its “original” shape. The traces of the great painting celebrating Ceasar’s imperial triumph remain on its walls—among its few fragments we can notice the silhouette of some African women, that keep on marching as slaves in a never-ending domination parade. Exoticism and erotism at their best.

Taking a few steps forward, a surprisingly empty giant map of Africa, where the only visible traces are the Italian colonies, and the inscription on the wall still shouting out loud “Tireremo dritto—We’ll go ahead.” An apparently inhabited land, with no women nor men, no identity nor history, neither names nor languages: the colonial power sees it as such, whilst taking it over and (re)naming cities and places, marking borders as straight as a line traced by default. Aside the map, a list of colonial victories articulates the unilateral temporality of the conquest. In its specific characteristics, the fascist epoch colonialism continues the symbolical “whitening” process started right after the unification, which assimilates and slowly deletes the internal line of color—the backward South is not white either—and projects the alterity on the colonies, literally making Italians white. In this “philological” restoration, in which the imperial eagles and the pictorial fasces are taken back from the warehouses where they had been confined and accurately placed back, nobody has felt the need to contextualize, to situate, to tell the presence and the meaning of the multiple fascist, racist, imperialist signs inscribing the space. This is one of the many examples present in Rome, that says a lot about the relationship we have—do we? Do we actually want it?—with our almost completely removed colonial memory.

(we) are not Gil, intervention at WeGil for Short Theatre, 2019. Photo Claudia Borgia.

On the WeGIL website, the official description of the space never mentions, not even superficially, fascism nor colonialism. The building seems to have been erected outside of history. Today “the historical Trastevere’s building now marrying rationalist forms” wants to become a cultural hub at disposal of the city, and it is even renamed as “WeGIL, where We is opposed to the overexposed ‘I’ of our daily life, implicitly proposing a concept of ‘opening’.” Even if we wouldn’t use the English language the literal meaning of the new name is We Fascist Youth! The homepage description ends with an emphatic, almost romantic tone “WeGIL: the new space with an ancient heart.” Which heart? What antiquity? What history? What epoch? The omission operation is not only bad because we are speaking about fascism, thus of a dramatic page of our history and of our national narration (considering that not to talk about it is a precise, not even that ambiguous choice), but because there is an attempt to subtract a space, a place, a name to time. We insert in History what we wish will be defining us—or not, we “patrimonize” with specific modalities what we wish or wish not to become part of our na(rra)tion, of our cultural patrimony and our national identity. As the construction of the history of a State that turns territories and places into neuralgic nodes, toponymy is never meaningless and remains opaque only when unquestioned.

To name and to rename means to confer reality, to recall a meaning shared by a community or alleged as such. Now if the wider community, in this case the nation, is built upon cultural devices like the construction of a city, thus its memory and imagination, then also the spaces and what signifies them inform about myths and symbols, about a history to forget or to remember. Through monuments, cultural objects, spatial organization, architecture, the cultural patrimony carries within a fundamental historical meaning of memory, culture and assumed shared values. Deciding to restore and reopen a space like the ex-GIL is not a neutral act, since through this place the city decides what to remember and what to forget, what identity is referring to and even assuming without any kind of concern. This is why, as feminists, we must unveil the superficially conducted process of patrimonialization of a fascist place that recall Italian colonialism, an act that heavily silences and subsumes. Before we can spend even a few hours there, we must tell the whole story of this building.

(we) are not Gil, intervention at WeGil for Short Theatre, 2019. Photo Claudia Borgia.

If we do it with a feminist gaze, we can’t but notice that women are represented by a male colonial gaze. There is a recurrence in metaphors sexualizing the colonial action. The land to conquer is often compared to an obscure body, pure matter without history to own and penetrate. Beside the metaphor, the colonial war advances through body abuse and rape, sealing in one figure patriotism and male virility. An analog construction recurs in the actual racist and xenophobe rhetoric of invasion, agitating the masculine fear of penetration and feminization of the male body: as the body of a white innocent lady, the Homeland must be defended from the black bodies menacing her integrity and pureness. Borders mark the limit of the sexual identity of the Nation-body, and it is precisely on borders that metaphors on security, intended as untouchability and impenetrability, come into play.

It is no coincidence that feminist words and practices have indeed unveiled issues such as colonialism removal, as well as the knot tightening colonialism to patriarchy. From the anasyrma (the gesture of lifting the skirt to show one’s genitals—be it artificially assembled or biologically feminine) in front of Rome’s Altare della Patria (Homeland altar) and Mussolini’s obelisk to transform it into a dilDUX, to the pink paint leaked on Indro Montanelli’s statue during the March 8th demonstrations. The journalist, an acclaimed bipartisan cultural figure, was also a soldier in the Italian colonization campaign and always strongly sustained such endeavors, as demonstrated in the infamous footage of the interview by the Italo-Somalian writer Elvira Banotti regarding his twelve year old “bride,” an unbearable linguistic mask to hide the pedophile and rapist truth. The power of the counter-narration has emerged both from this practices and different forms of denunciation, in regards to an Italian colonial regime still inhabiting the minds of the public opinion. Colonialism proceeds indeed through economical and military ways, always in need of parallel narrations—so that the “epistemic” cultural linguistic violence is added to the material violence, imposing a vision of the world and a series of devices of cultural hegemony. The material conquest of a territory is always in need of a map, always in need to give names to things.

(we) are not Gil, intervention at WeGil for Short Theatre, 2019. Photo Alessandra Cardinale.

Throughout the years, several practices have attempted to build utopias in the present in Rome. Our biographies have crossed within the movements, as we created turmoil in a city like Rome, eternally blocked by institutional politics, incapable to give space to voices and cultures that do not reflect the idea of the heterosexual middle-aged white male, owner of goods, women and children: the aural measure of a world in perpetual crisis. The removal of Italian colonialism interrogates nonetheless these precious spaces as well, where it is now impossible not to realize the almost homogenous color of the bodies inhabiting it, of memories and narrations. If Carla Lonzi was already speaking of the urgency for a cultural decolonization of patriarchy, present Histories push us to decolonize ourselves from the totalizing certainties around forms of liberation and expression, from speaking on behalf of Others, and from habits that render difference invisible and alliances difficult.

Considering these multiple trajectories—we asked ourselves—how to intervene on the ex-Gil space? A text that would explain or simply contextualize below the colonial map of the Mussolinian Africa, a caption isn’t enough. Yet a caption isn’t enough in general, to rethink patrimonization. The cultural patrimony must be re-created, re-inhabited in order to go from the idea of a temple museum narrating the nation, to one that would see bodies and shared memories in action, where the feminist gaze would take up space and speak up. We need a more radical action—we didn’t want in fact to solve the problem of the building’s colonial and fascist identity, but rather the opposite. We wanted to raise the issue, stir things up; not to cancel but rather rewrite, overwrite. (we) are not GIL is nothing but a modest mural intervention, yet both an imaginative exercise and a decolonization practice.

Non Una Di Meno, Dildux, 8 marzo 2018.

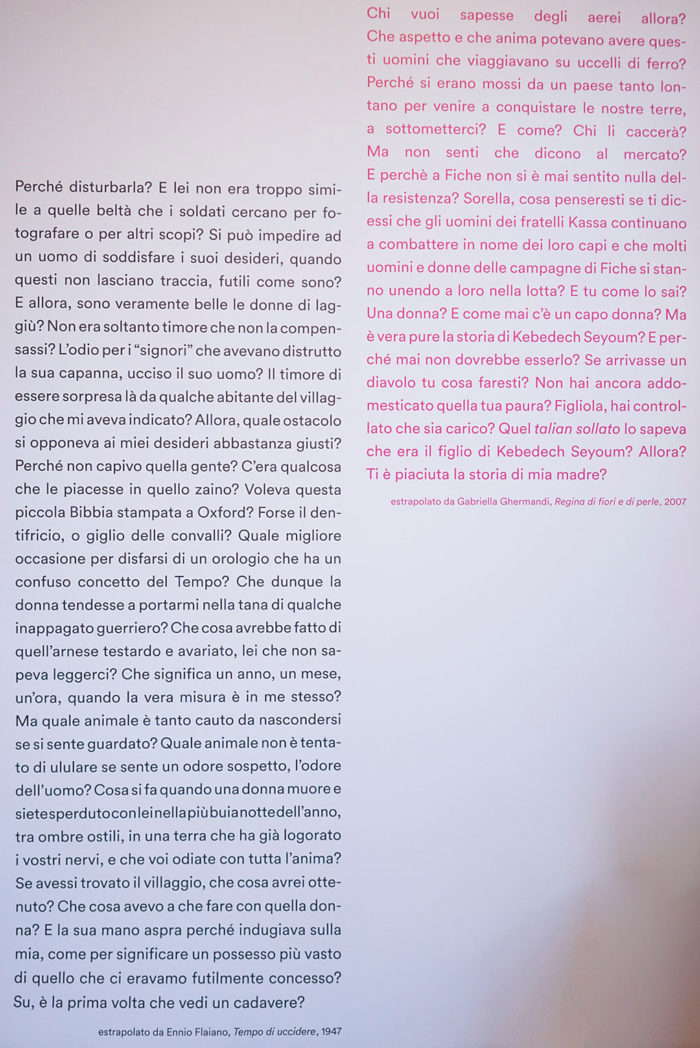

So, rather than using an explanatory caption that would pacify and self-absolve us, we formulated a series of questions to open and challenge both ourselves and the space. A text that is also an action, an attempt to remain a body in critical relation with the body of the building in order to de-neutralize it. Moreover, with the help of Italo-Etiopian writer Gabriella Ghermandi’s words, more questions collided with ours. In Regina di fiori e di perle (Queen of flowers and pearls, 2007) Ghermandi tells the story of the Ethiopian resistance from Italian colonization, deciding to rewrite some of the events as previously told in Tempo di Uccidere (time to kill) by Ennio Flaviano, a Premio Strega winner novel (the most important Italian literary price) in 1947. Despite the critical tone underlying the narration, Flaiano transfigures Italian soldiers’ efferate violence in an almost surreal way, committing genocides with bureaucrats’ coolness, raping young and adult women, eviscerating pregnant women, taking part in that active process of removal of the most obscure side of the Italian colonial story, which the “philological” restoration of the ex-GIL is unfortunately an actual witness of. What comes out from that novel then, inasmuch as from this building, is that there is only space for emotions, affect, words—self-exculpatory, if not even self-celebratory, of the talian sollati, Italian soldiers, there where other bodies are incomprehensible, animalistic, ultimately rapable and forgettable.

On the contrary, we tried to ignite a(n) (im)possible dialogue between the questions that move Flaiano’s “good Italian” with the questions of one of Gherlandi’s narrators, when she remembers her own experience in the Ethiopian Resistance, guided by Kebedech Seyoum. Questions that tell, more than ever in a building dedicated and destined to the fascist Youth, the urgency to face the ghosts inhabiting Rome. Questions that entangle voices in a temporal knot of a disarming actuality: to make memory is an act as symbolical as material, as well as political. These questions unveil the relationship among those who refuse the narration of the colonizer, while it becomes necessary for each of us to bare the risk to question and transform the disparity among us. The way to do it is still to figure out.

Non Una Di Meno, Vernice su statua di Indro Montanelli, 8 marzo 2019.

Shall we play colonized and colonizers? Where are you vulnerable? Is my skin a privilege? What language do your ghosts speak? Are Italians white? When did we become white? What’s our imagination of Italian colonialism? Who has been silenced? What has been told? Is white a neutral color? What kind of animal are you? To go ahead or to keep ourselves inclined? What does a monument say? Where is Libya? Is forgetting an action? Am I innocent? Is a border a straight line? Who can speak? Who’s a civilian? Who’s superior? Are we the margin of which centre? Are you speaking on my behalf? Why am I speaking on her behalf? Where’s Ethiopia? Is the Mediterranean a border? Is it possible to draw a straight line on water? Why is this map of Africa empty? Where do I learn to execute a gesture? Who would you like to be? Those objects in museums, where do they come from? Where are the obelisks from? What is whiteness? Where is Somalia? Is the Other indistinct? Does the Other exist? Is the Motherland a Woman? Is the territory a body to penetrate? Were there women in the colonies? Do you know any African History? Is Time European? Is Primitive that which comes first? Civilization or colonization? Is the colony a place? Can the body of the Other be exposed? Who can represent the colonizer? How to construct memory? Where is Eritrea? Who’s the keeper who keeps? Is Patrimony a property of the father? Is remembering feminist? Is it possible to restore fascism?

“Why shall we disturb her? And wasn’t she too similar to the beauty soldiers tried to photograph for other purposes? Can we stop a man from satisfying his desires, when these don’t leave any trace, futile as they are? And so, women down there, are they really beautiful? Wasn’t it just fear that I couldn’t compensate her? The hate towards the “landlords” that had destroyed her shelter, and killed her man? Fear of being overtaken by some villagers who she mentioned? What was against my quite-fair desires? Why couldn’t I understand those people? What did she like about that backpack? Did she want this small Bible printed in Oxford? Maybe the toothpaste, oh Lily of the valley? What better occasion to get rid of a watch that messed up with the concept of Time? Then thus the woman would have the tendency to take me to the shelter of some unsatisfied warrior? What would she do with that stubborn rotten tool, she who couldn’t read? What does it mean a year, a month, an hour, when the real measure is within myself? What kind of animal is as cautious to hide when it feels looked at? What kind of animal is not tempted to howl when it smells a suspicious smell, the smell of a man? What to do when a woman dies and you are lost with her somewhere in the darkest night of the year, among hostile shadows, in a land that already worn your nerves out, a land you hate with all your soul? If I would have found the village, what would I have obtained? What did I have to do with that woman? And her harsh hand, why was it lingering on mine, as if to signify a wider possession than what we would allow ourselves vainly? C’mon, is it really the first time you see a dead body?” Excerpt from Ennio Flaiano, Tempo di uccidere (Time to Kill), 1947

“Who do you think would know about the planes? What look and what soul could these men who travels on metal birds have? Why did they come from so far to conquer our lands, to subdue us? And how? Who will kick them out? Don’t you hear what they say at the market? And why in Fiche no-one ever heard anything about resistance? Sister, what would you think if I’d tell you that the men of the Kassa brothers keep on fighting in the name of their lords, and many men and women from the Fiche countryside are joining them in the fight? And you, how do you know? A woman? And why there’s no woman in charge? Is Kebedech Seyoum’s story true? And why the hell shouldn’t it be? If devil would come what would you do? You didn’t domesticate that fear of yours yet? Daughter, did you check if it’s loaded? Did the talian sollato, did he know he is Kebedech Seyoum’s son? So? Did you like my mother’s story?” Excerpt from Gabriella Ghermandi, Regina di fiori e di perle (Queen of flowers and pearls), 2007

Entanglements

Paola Granato

During a conversation at the John Cabot University in Rome, Paul B. Preciado mentioned how he imagines the university of the future. The philosopher has brought forward the hypothesis of a place with no teachers, where knowledge becomes a collective exercise, in the formulation of another kind of school, where it’s not the title that matters, but where we go to become more sophisticated. As the university is indeed a place for knowledge production yet this knowledge is legitimated by its given value. Although we’re nowhere close to this model, we can still detect few others that share a similar kind of vision, like several Free Schools born in the artistic scene, which question the way we organize and share knowledge, by creating possible alternative models in a para-academic form beyond the productive logics.

These models highlight the dichotomy expressed by Chantal Mouffe in an article from 2012, Strategies of radical politics and aesthetic resistance. “Should critical artistic practices engage with current institutions with the aim of transforming them or should they desert them altogether?” Mouffe asks, outlining some possible ways and underlining the fact that art institutions have become capitalism’s accomplices, as they couldn’t provide any longer the space for artistic practices of institutional critique. Alongside an “exodus strategy” from the institutions, Mouffe proposes instead an engagement. According to Mouffe “(C)ritical artistic practices do not contribute to the counter-hegemonic struggle by deserting the institutional terrain but by engaging with it, with the aim of fostering dissent and creating a multiplicity of agonistic spaces where the dominant consensus is challenged and where new modes of identification are made available.”

The relationship with the institutions is still a central issue, and to a certain extent is mainly a matter of overcoming the binary contemporaneity is entrapping us into. In the fourth chapter of Dialogues titled Many Politics, Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet oppose the dichotomy between “a globalizing State, the master of its plans and extending its traps; and then, a force of resistance which will adopt the form of the State even if it entails betraying us, or else which will fall into local spontaneous or partial struggles, even if it entails being suffocated and beaten every time.” Because “(I)t is along the different lines of complex assemblages that the powers carry out their experiments, but along them also arise experimenters of another kind, thwarting predictions, tracing out active lines of flight, looking for the combination of these lines, increasing their speed or slowing it down, creating the plane of consistency fragment by fragment, with a war-machine which would weigh the dangers that it encountered at each step.”

Sara Leghissa/Strasse + Carlo Fusani. Residency project TONIGHT NOT POETRY WILL SERVE at Short Theatre, 2019. Photo Claudia Pajewski.

Indeed these active lines of flight are the ones defining the virtuous processes of the Art module, coordinated by Ilenia Caleo and Isabella Pinto, as part of the Master in Gender Politics and Studies, directed by Federica Giardini at Università di Roma Tre, whose work happens in close collaboration with Short Theatre, a festival aimed at building community while investigating the contemporary through radical artistic practices. This year, the festival came to occupy a controversial space, namely the building of ExGil in Rome—Palazzo della Gioventù italiana del Littorio, built in 1933. A problematic venue which sheds light upon a never-problematized-enough colonial past, today renamed as WeGil.

The festival decided to commission Ilenia Caleo, Isabella Pinto, Serena Fiorletta and Federica Giardini to think of an intervention that could re-signify the space, which resulted in the artistic action (We) are not GIL, not meant “to solve the problem of the colonial and fascist identity, but rather raise the issue and shake the ground.”

Continuous openings, lines of flight and configurations of alliances that are aimed at scanning through this complex present and delivering what usually remains outside the academia. Spreading knowledge is a political act, inasmuch as it is to imagine a festival and to (re)write the places we cross. “Thinking in things, among things—this is producing a rhizome and not a root, producing the line and not the point. Producing population in a desert and not species and genres in a forest” writes Claire Pannet to Gilles Deleuze, if “one must multiply the sides, break every circle in favor of the polygons” he states, how can we inhabit institutions otherwise? How can we queer the institution?

Sara Leghissa/Strasse + Carlo Fusani. Residency project TONIGHT NOT POETRY WILL SERVE at Short Theatre, 2019. Photo Alessandra Cardinale.

Intense days, afternoon classes, evening shows and meetings at the Short Theatre, to witness together and discuss the day after in class; the need to share and reconnect the theory to the artistic gesture and vice versa, because it is never a straight line. Two inseparable paths, the one of the MA and the one of the festival, giving each other strength through their reciprocal gazes in analyzing the proposed topics. In Valeria Luiselli’s Archivio dei bambini (kids’ archive), she perfectly describe a comparable feeling as such: “I remember when I read Sontag for the first time, as the first time I read Hannah Arendt, Emily Dickinson and Pascal, I had continuous sudden forms of ecstasy, maybe of micro-chemical nature—as small lights that glimmer in the depths of the cerebral tissue—what a person feels when finally find the right words to define a very simple feeling, which remained nonetheless unspoken until that very moment. A match lit in a dark corridor, the cigarette ember when smoking in bed, the burning ashes of an extinguished fire; none of these things produces a light bright enough to reveal anything. It is the same for other people’s words. But sometimes a small light can make you aware of the dark unknown world around that glow, of the immense ignorance around what we believe to know. And the admission of coming to terms with darkness is more precious than all the knowledge we could ever accumulate.”

In Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective, Donna Haraway speaks of situated knowledges, where “we seek those ruled by partial sight and limited voice—not partiality for its own sake but , rather, for the sake of the connections and unexpected openings situated knowledges make possible. Situated knowledges are about communities, not about isolated individuals.” If there is something in common among those women we met during our classes, it’s precisely their positioning, as they all introduce themselves by telling fragments of their biographies: who said to be a mother and a feminist, who used a project as a pretext to talk about friendship, who evoked a seminar on the mountains to talk about encounters. Stories that have caused commotion for affective reasons and unsentimental ways of falling in love that can affect the political.

“It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.” Donna J. Haraway

A woman, a caravan on the background, lots of people sitting in front of the ExGil listening: the staircase in front of the building is packed with people, the crowd reaches the Little Fun Palace’s caravan parked ahead. Behind the entrance heavy door the festival audience is engaging with MK dancers on their participatory piece Bermudas Forever, the music played by Bunny Dakota is distant yet present, to remind us that the outside always comes with an inside. While Françoise Vergès begins to speak it’s impossible not to think about the giant map of Africa on Gil’s walls, and to a past we didn’t deal with, to a “removed” that sometimes comes violently back to the surface. But now, the same space has been transformed by the questions juxtaposed on the same walls—“Shall we play colonized and colonizers? Is the territory a body to penetrate? Why is this map of Africa empty?”—by the projects inhabiting it, by the presence of those crossing it, and by the words in the air, inside and outside. Vergès speaks, among other topics, of breathing. Even breathing can be colonized, she says, but we need to breath, and how can we construct spaces where we can do it? In its apparent simplicity, this is the issue we should work on—I look around and I see the signs around me and for a moment, I breath.

Sara Leghissa/Strasse + Carlo Fusani. Residency project TONIGHT NOT POETRY WILL SERVE at Short Theatre, 2019. Photo Claudia Pajewski.

There are shows made not to abandon one’s ghosts—actress, playwright and founder of Fanny & Alexander, Chiara Lagani explains. Together with actress, playwright and founder of Ateliersi, Fiorenza Menni, they held a class that from their piece Storia di un’amicizia (history of a friendship) went on recounting an artistic practice developed throughout the years that contributed to build a theatre scene based on research. As friends and actresses they are the protagonists of the theatre show Storia di un’amicizia. Chiara asked Fiorenza to read Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, and Fiorenza read it while looking for Chiara in it. The writing process by Chiara Lagani works as a cinematographic montage, defecting linearity, constructing hypertexts, linking individualities and connecting apparently distant universes together. The score was curated by Fiorenza Menni who has researched some classic contemporary choreographies, to be incorporated with some daily gestures. As we have been told by Vergès, our future takes shape by working together.

Bodymetrics with Liana Borghi, Federica Giardini, Beatrice Busi, Alessandra Masala, Giulia Crispiani introduced and moderated by Ilenia Caleo and Isabella Pinto. Little Fun Palace for Short Theatre, 2019. Photo Alessandra Cardinale.

The image of the cat’s cradle appears for the first time during the meeting with media sociologist and teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts in Palermo Federica Timeto, who gave an introduction on Cyberfeminism. Cat’s cradle and string figures becomes a concept in Donna Haraway’s latest book Staying with the Trouble “Playing games of string figures is about giving and receiving patterns, dropping threads and failing but sometimes finding something that works, something consequential and maybe even beautiful, that wasn’t there before, of relaying connections that matter, of telling stories in hand upon hand, digit upon digit, attachment site upon attachment site, to craft conditions for finite flourishing on terra, on earth.” This image returned when we visited Maria Lai’s exhibition at MAXXI Tenendo per mano il sole (Holding the sun by the hand). Curator and researcher Donatella Saroli accompanied us, proposing several readings connected to Lai’s practice. We gathered in a museum hall and we read about string figures out loud: an explosion of connections, references and openings, Lai’s portrait playing string figures. Weaving textures, the loom and the warp, and Lai amidst a certain type of feminism. The usage of the excess and the leftover as a precious material for the construction of worlds that speak secret languages, for her—in Isabella Pinto’s words—the loom is a diffractive tool. The work Legarsi alla montagna is in fact playing cat’s cradle, includes the whole town of Ulassai, in an entanglement of skein and thread.

Liana Borghi has a delicate voice, as anyone speaking softly, she demands you to make space inside to focus and welcome what’s been said, in an ego-exercise that urges calm and attention. Borghi introduces us to Karen Barad and her Poet(h)ics of diffraction. “Diffraction is used to intra-actively read phenomena, events, concepts and texts, producing narrations that involve us into emotional diffraction, and demand us to consider unusual configurations of time and space requiring new approaches (pattern of engagement/models of application), aware of the matter and meaning necessary in carrying out new multidimensional cartographies and other representations.” Practice turns into theory, and vice versa in the conceptual and practical tread of this path we crossed together, where we encountered artistic theories and practices, we got the chance to observe them as “entanglements that cross and produce our bodies as part of a continuous active and performative reconfiguration of the world, involving race, class, gender and sexuality, because the world produces itself through this multiplicity of entanglements.”

No revolution without songs

Giulia Crispiani: How are you, how is Françoise Vergés today and how does she feel?

Françoise Vergès: Well, I feel feisty, like I need to stay awake. I also feel the need to read a lot of things to be able to bring together so many conflicting elements of what’s going on in the world, so I don’t fall totally into a kind of idealized hope nor despair. I can see what we have in front of us and at the same time a formidable resistance everywhere. The struggle is going to be difficult and long, but it has always been so. This is how I feel, I am not going to hide the fact that there are moments I would want to have a vacation…

…a vacation from resistance?

…no but from having so many thoughts going around my head, the feeling that I am falling behind in terms of listening, reading, doing. More than ever, it is not a binary thing, you know the bad people in front of us versus the good people, though there is always an element of that, the “bad” is coming in so many different forms and ways, that sometimes I am afraid I can’t anymore and need some rest. This summer I read feminist fiction, specifically a rewriting of the great Greek myths where so many women in the Iliad and in the Odyssey are minor even though they are pivotal characters. Reading these novels that put them back in the center of the narration was at the same time restful and absolutely awakening. I never read these myths from the point of view of women, as told by the ones who are on the side of defeat and who know that they are going to be enslaved, raped and married by force, that they would have to follow the men who killed their husbands, sons, brothers and so on. It triggered a thinking about war and how war is absolutely a masculine/macho endeavor, but also how war really deeply destroys social ties. That was a way to think yet taking my mind elsewhere.

Then going from what you read last summer and how you feel today, I’d like to go back to when you were a young activist, what made Françoise Vergès, what are the books that shaped you, and what should we read? Although you mentioned before that you did not start from the theory…

I don’t know if it’s reading… No, it is not the theory that made me. I remember when I was little, following my mother and father, and seeing people who were workers in the sugar cane fields or domestic workers, I saw how racism and capitalism affected their bodies, I understood what capitalism does to you, not just the visible exploitation, and the way in which visible exploitation is theorized—surplus value and so on—but the slow violence, less visible, what it does to the body and the psyche. I also observed the way in which power fabricates consent and that was a very important lesson for me. Even though for a long time I saw things in a binary way, what I had observed as a child slowly transformed my thinking, made me realize that “power is power.” When I was younger, electoral fraud systematically happened in Reunion in favor of the racist right wing, and my parents were fighting for voting rights. The elections were incredibly violent, I was following my parents and saw the private militias of the conservatives beating up people and stuffing the ballot box; in the evening I was rageous and I remember my parents saying “Françoise, these are fascists, they are not going to let us win.” It was not that victory could not be obtained, but to grasp what is the enemy about, what we are facing to avoid moralizing and think “this should be like that, people do not understand, why do they vote like that…” It’s not that people are stupid or they are voting against their own interest, or that colonized people are weak, no. We should always consider how power fabricates consent, through fear, through repression of course, but also through ideology—which sends the message: “if you remain quiet you’re gonna get some crumbs and we will not bother you, your children will go to school and you will get a job and even some raise, some promotion but don’t protest, don’t raise you head, don’t contest and you may have a quiet life”, and yet that quiet life is fragile, really fragile. I appreciated even more the courage of those who fight back, who show no fear, a deep, real courage that moved me to tears.

A personal memory: when I was 11, the police went around to see the parents of some of my friends and said your daughter should not be a friend of Françoise Vergès, her parents are communist and anti-colonialist, beware! I had a close friend with whom I spent a lot of time, I was like a member of her family, but one day, as I was coming to her home, her mother came to the door and said to me—sorry, you cannot come anymore. This is the way power operates not just by beating you up, or sending you to jail but by instilling in you fear and obedience. This is something that anticolonial fighters, feminist of the global South, queer, indigenous peoples, all oppressed have analyzed, the need to decolonize the self, decolonizing our minds, Ngugi Wa Thiongo wrote. My father was underground for more than two years, to disobey the French State and show that its hegemony was not that powerful, that even on a very small island like Reunion, where everyone knows everyone, he could be hidden by the people. The state, which saw him as a “terrorist,” did not really control everything. During these two years my mother was threatened, there were police searches at our home, and so on. My point is not so much about what we had to experience, but the fact that for some of people later it was my parents’ fault, they said “but your parents should not have been that active,” as if it was the state which was at fault but my parents. We were children and we witnessed police searches, repression, and we could not have freedom, and my mother was threatened, people arrested or harassed for supporting the anticolonial movement in a postcolonial French territory … no, my parents were not responsible! It was the neocolonial State.

All these experiences were very important for me, I understood how power fabricate consent and use fear. Judging people for not acting was worthless, it was more important to nurture and support dissent. I was told a story and though it may be apocryphal, it exemplifies how fear is used in a South American dictatorship (no matter which one): when the police came to arrest people, their neighbors were visibly closing the windows as if to say to the police “we’re not seeing, we will not be witnesses, trust us we’re not going to say anything.” What I mean is that I saw how power instills in people a conformism that guarantees the kind of peace it wants—“be respectable, the State is protecting you and if you don’t protest, your life will be easy.” Hence, my deep admiration for the courage of women and men who daily fought racism, inequality, sexism and exploitation. I insist on this because there is a tendency to celebrate “machismo heroism” and dismiss the quiet and powerful courage of black and women of color.

Françoise Vergès lectio magistralis at Short Theatre, 2019. Photo Alessandra Cardinale.

What have you learned since the beginning of Décoloniser les Arts, what have you learned yourselves—collectively, and how did the questions changed throughout these few years of practice?

Every revolutionary movement has always had a chapter in culture. Always. There’s no social project without a chapter on culture. Today the question is: what is the language content of decolonized arts? It’s not “ok let’s put some black and brown people in the institution,” (although it is important), but rather what would decolonized arts be? I don’t have a clear answer, I see it as a process we have to go through to unlearn in order to learn, and wondering what we can learn from European art. I am moved when I see delicate jewelry, crafts, pottery, woven textiles from different parts of Europe. I am a visitor of museums and I like to look at how people ought to adorn themselves, I find it very moving to look at clothes, jewelry, make up of centuries ago and that existed everywhere. The desire to transform one’s body into art.

I am not rejecting European art for European art, but I am questioning the art history that continues to dominate despite so many works, shows, debates. It is not about replacing one body of work with another, it is about the way art history has been written, the way some objects are classified in the realm of ethnology and others as art.

…especially considering the erasure of what was there before that…

exactly. It’s about what is art, what do we think is an artist.

What if we imagine the world as a household, could we imagine the earth to be our home and that we would all be mothers—beyond the dichotomy that only females are mothers. In this context the issue of responsibility comes through, inasmuch as care and sustainability. Can we turn responsibility into a virus through culture?

Yes but we will have to address the deep inequality still present today; the North has benefitted from the looting and the destruction of the South, and the South is living with that now; when you see the devastation of Porto Rico or the Bahamas, or if we remember Katrina in New Orleans, the catastrophe does not strike equally, poor black and brown people are the greatest victims, during the catastrophe and after because they get out even poorer. This idea that we share a planet equally—no “we” don’t share a planet. We don’t share it equally. What does it mean to share it equally? Are we all equally responsible for what has been done to the planet? Who is really caring for the planet? What does it really mean to take care? If we really want to take care, it means we have to fight capitalism. Okay let’s say, let’s imagine we changed it. To do what? What is post-capitalism? How will we be sharing the world not throughout hyper-consumption and hyper-production, which does not mean as a hegemonic discourse would like to say that we are not going to go back to “the candle,” how do we take care of seven billion people who need access to clean water and everything that makes your life a little more comfortable? What kind of economy would allow that? What kind of sharing would allow that?

For instance, when we read about the forest burning in Africa and South America, we have to look at the consequence of agro-business greed, but also at the ways in which international laws of commerce, trade and the practices of agro-business are destroying the lives and the means of living of billions of poor cultivators, who are often women, and then why they may also put fire to the forests. But also how they resist. We have to look at a local, regional, global system of production. So yes “we” can say “we” have to take care of the world, but the world is also under that very economic system of capitalism that cause poor peasants to either die or burn the forest to survive. When we say: “you should not burn and slash the forest,” we chose to ignore the making of an entire chain of causes and consequences produced by the big multinationals, agro-business, the international trade laws. In Madagascar, damage is being done to an incredibly specifically rich biosystem. NGOs are coming and saying to the Madagasi “you don’t know that you should protect your biodiversity?” People are dying of hunger! Multinationals are coming and buying huge parts of the island, extractivist multinationals are destroying the island and looting resources: we must support Malagasi peasants in their resistance to that looting and for decent ways of cultivating and living in dignity. We have to consider all this, we cannot just say let’s share the planet as if it has been shared equally. It’s important to think through that instead of coming up with very easy solutions. It’s going to take us a while, some of us will not see it but we have to fight, and think hard and imaginatively. It is not that easy to imagine a post-capitalist world, capitalism hinders imagination. This is where our imagination should focus and it’s not easy. It is much easier for us to write about dystopia and the world going bad.

Françoise Vergès lectio magistralis at Short Theatre, 2019. Photo Alessandra Cardinale.

In one of your essays you write about the joyfulness of the struggle, this topic for me is central in sharing and collectivity. I recognize that this is really what gives us the energy to go on and to think without having “to take a vacation from thinking.” Besides breathing and being together, how can we build spaces where we nourish this joy?