Communication Guerrillas

This essay is one of the chapters of Underground Streams: The first complete history of revolutionary artistic utopia from dadaism to accelerationism (published in Italian by Not). In a broad recognition throughout a whole century, the book carefully reconstructs the details of a long counter-cultural history between Europe and the States and their shared heritage. From Dada to the Situationist International, from the violent fringes of American Marxism to Italian Operaismo, from communes to cyberpunk, from Neo-ism to electronic civil disobedience, to end in the ocean of multiplicity and in the abyss of a Lovecraftian desire, where this swarm reaches the core of late capitalism, between cybernetic occultism and subjectivity withdrawal. A necessary tale to orientate oneself through the transformations of the 20th-century antagonisms, often relegated to minor histories but actually symptoms of the same liberation, one where political turmoil, acid drive, anti-art, dreams and post-industrial culture reconnect in «weird temporalities» in denial of any sort of historicization. This specific chapter begins in Viterbo and, unfolding from the Neoist Alliance, arrives to “the many” Luther Blissett.

Viterbo Black Magic

Something strange was happening in the city of Viterbo in January of 1996. Spray-painted messages were appearing on the ancient stone walls and their content shocked the mostly Catholic, conservative population: they were satanic in character. At first, it was just enough to cause a little uneasiness, but as time went on, the graffiti increased. Shock became dread, and dread verged on panic. The media entered the game, and a series of letters began to appear from anonymous sources. They alleged something about a conspiracy: the local right-wing political figures linked to neo-Nazi groups, ties between Nazis and black magic.

It continues for months, and then in May the remains of a black mass is found in a forest outside of town: “bowl, mud, candles, and burned photographs”, along with a “satanic tape”. All it was smashed to bits, as if some sort of “violent fight” had occurred. The public fear is stoked further by extensive coverage, which is then fueled by the arrival on the scene of a vigilante group called “Committee for the Safeguard of Morals”. When a video of the black mass appears, replete with the off-camera sacrifice of a “screaming virgin”, the story leaps from the local press to the national media. As Italy turned its eyes towards Viterbo, a second tape was delivered to the national television station RAI Uno. Sent by somebody named Luther Blissett, the tape was an ‘extended’ cut of the sacrifice, which in turns out didn’t end in blood and murder, but “with a tarantella in which the ‘Satanists’ and the ‘virgin’ hold hands, dance, and sing along.”

What had transpired had effectively utilized the national media to embarrass the local media. The culprit behind the prank, the elusive figure of Luther Blissett, had done it as an act of “media homeopathy”. Detailed in a book that analyzed the country’s willingness to engage in media panic and the way that the media seemed dedicated solely to feeding the flames of panic, media homeopathy involved a hijacking of the channels of communication in order to feed it back to itself. The result was the revelation of the monumental artificiality of the postmodern world’s very infrastructure, a system that could only be regarded, like Jean Baudrillard urged, as some kind of simulation. What was more important, however, was that this very artificiality was precisely the system’s weakest link. Luther Blissett had found a way, it seems, to induce malfunctions in the simulation.

Back Again

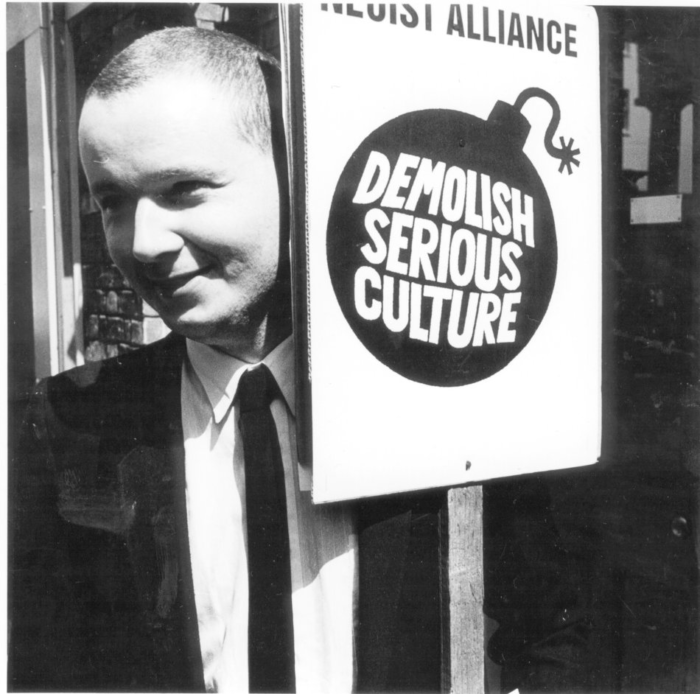

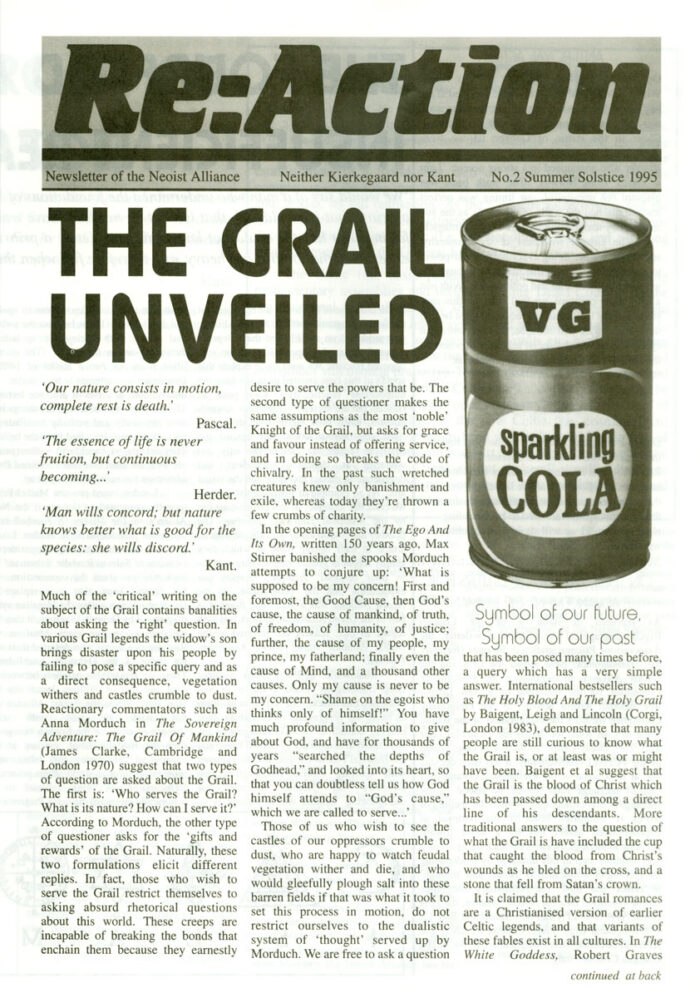

In the aftermath of the Art Strike, Stewart Home embarked on a new venture. He discarded the moniker of Praxis and re-emerged as the solitary member of a new group: the Neoist Alliance. Intriguingly, the Neoist Alliance was not intended as a continuation of neoism, and Home certainly didn’t backtrack on his criticisms of the (non-)movement from before. Instead, it was a calculated appropriation in response to the neoism’s own fascination with the Art Strike. The Art Strike had been intended to disavow not only the commercial art world, but the neoists as well; by taking it up as part and parcel of the neoism program, this vital element had been liquidated. Home’s critique of the movement was that it constituted the cheapening of the concept of the avant-garde, with an especially egregious blow dealt to futurism. The Neoist Alliance, in many respects, constituted a negation of this cheapening (shades here of the generative-degenerative structure that Isidore Isou promoted through Lettrism) and a rejection of the nullified progress that it sought, that is, the conversion of the open future into hollow and neutered sense of newness. Tellingly, the journal of the Neoist Alliance was titled Re:Action, a pun emphasizing “reaction” as well as a return to action proper.

Two Neoist Alliance manifestos were issued, both of which continued to advance the Marxist-futurist fusion that Home’s earlier work had trafficked in, while also veering away from the veneration of the beauty of the machine (which was covert in Marx but overt in the futurism) and moved towards a fascination with the ugly and the unkempt—noting, perhaps, the subterranean passage that linked together people like Gruppe SPUR and Hundertwasser, with their desires for mold and slime and kitsch and the cobbled-together. The first manifesto is as follows:

- RELIGIOUS. To undermine all monotheistic creeds and to propagate crazy cults, mysticism, para-science and anti-philosophies.

- ETHICAL. To introduce debasing codes and practices, corrupt morals, weaken the marriage-bond, destroy family life and abolish inheritance.

- AESTHETICAL. To foster the cult of the ugly and whatever is debasing, decadent and degenerate in music, literature, and the visual arts.

- SOCIOLOGICAL. To break up large corporations and abolish privilege. To provoke envy, discontent, revolt and class war.

- INDUSTRIAL AND FINANCIAL. To lower the ideals of craftsmanship and abolish pride in handicraft. To encourage standardization and specialization. To wrest control of finance from the corrupt ruling class.

- 6 POLITICAL. To secure control over the press, broadcasting, cinema, stage and all means of influencing public opinion. To break up the ruling class institutions from inside by creating dissensions.

The second, meanwhile, offers much of the same, albeit in shorter, more immediate form:

- The active appropriation of tradition, where restriction is realization.

- The production of a discourse that is simultaneously artificial and natural.

- The disruption of normal temporality by following AND anticipating tradition.

- The production of a second nature from the material supplied by actual nature.

- The testing of our theoretical and practical activities before tradition.

- The dissolution of the restricted accord of the concept in subjective quickening of our cognitive faculties.

A classical characteristic of the avant-garde is the feud, the struggle against not only the past and its sentimentality, but against groups competing to lay claims on the future—and more often than not, the primary tactic of the feud is to unveil the linkage either between a given group and the past, or between that group and the bourgeoisie (which always, of course, leads back to the past). The Neoist Alliance was no different, and Home, who saw little different between aesthetic and political goals, spent considerable amounts of ink in the first issue of Re:Action in a conflict with British anarchist networks, namely those around the journals Further Two and the Anarchist Lancaster Bomber, as well as the Green Anarchist Network (with which the Anarchist Lancaster Bomber was associated).

The source of the conflict was multifold, but the immediate flashpoint was the allegation made in the pages of Further Two that the agenda of the Neoist Alliance was fascistic. Home’s response was that the Neoist Alliance was anti-fascist, and that the real fascists were the anarchists themselves. The language in the manifesto appears here to have been a lure, compelling the latent reactionaries to out themselves: “spoofs of this type assisted us in smoking out humorless reactionaries who pose a radicals but are secretly sympathetic towards fascism, since only those who think like right-wing bigots would rail against the desire to to ‘foster the cult of the ugly and whatever is debasing, decadent, and degenerate in music, literature, and the visual arts.’” Likewise, the political ideology promoted by these anarchist networks, which sought to foster a political universalism that subordinated other goals to its primary directives, was deemed by Home to be the reactionary impulse par excellence.

“While much of the anarchist and underground milieu call for unity, the Neoist Alliance is more interested in division and radical separation. It is to this end that we conjure up new memes and fantastic elementals which will facilitate the movement of particular social groups towards various goals. The desire for fusion found across much of the political spectrum is essentially fascist.”

Tellingly, the founder of the Green Anarchist Network, Richard Hunt, soon left the organization to start Alternative Green to promote a resolutely anti-modernism, pro-primitivist stance. Alternative Green, in turn, was of considerable influence on one Troy Southgate, whose National Revolutionary Faction (NRF) blended white nationalist ideology, Evolian mysticism, and anarchism into a heady fascistic stew. The NRF was close to the Transeuropa Collective, which had been set up by the neo-Nazi activist Richard Lawson; to close the gap, the journal of the Transeuropa Collective, Perspective, would eventually merge with Alternative Green. This soil composition of fascism, green thinking and anarchism nurtured Southgate’s new far-right movement, the so-called Greenshirts, as well as the National Anarchist movement, which to this day attempts to infiltrate small anarchist groups and mass movements alike.

For Home, Hunt’s trajectory was not aberrant, but the ultimate conclusion of the anarchist position in itself. Indeed, even before Hunt split and launched Alternative Green, the Green Anarchist Network was a haven for anti-modern, anti-rationalist politics. As Graham Macklin notes in his overview of the eco-anarchism-national anarchism axis, “Green Anarchist itself lacks a belief in positive human agency and appears entrenched in a misanthropic, ideological cul de sac eulogizing the far right’s use of indiscriminate terror against the ‘system’ as a means to achieve its own primitivist ends. Celebrating the age of ‘irrationalism’ editor Stephen Booth praised the Japanese religious sect Aum Shinrikyo responsible for the sarin gas attack on the Japanese metro and the American militia movement, particularly Timothy McVeigh who, Booth argues, had ‘the right idea’ in attacking ‘The Machine’.” Noting these trends, the Neoist Alliance circulated a memo to a non-existent group called the “Green Action Network”, a parody of the Green Anarchist Network. Lampooning the eco-anarchists as not-so-closeted Third Positionists, the memo cited European New Right figurehead Alain de Benoist on the “right to difference” between the various people of the world (this notion is itself the fundamental insight of National Anarchism). Going further, it attempted to draw together the communitarian ethos of the eco-anarchists with the fascist celebration of volk identity: “in works such as The Peasantry As The Life Source Of The Nordic Race, Nazi agriculture minister Walther Darré outlined a pastoral vision that is remarkably similar to the [green anarchist] ideal of small autonomous communities. The tragedy of National Socialism is that this idealistic movement allowed itself to be perverted by the bigotry of men such as Alfred Rosenberg and Julius Streicher, while reactionaries such as Albert Speer simultaneously bulldozed autobahns through the European countryside.”

Theoretical counterparts to these guerrilla stunts were staged. These included Green Anarchist Exposed! A Special Report by the Neoist Alliance, which argued that anarchism, because it makes itself ultimately a moral condemnation of oppression (as opposed to a structural one, like one would find in Marxism), it recourses to deriving both theory and practice from ultimately liberal grounds. This is the same route that fascism also takes, and because of this the paths followed by anarchism and by fascism are, in fact, one and the same. There is thus a largely unacknowledged and unrecognized radical identity between anarchists and fascists (thus making people like Southgate and groups like the National Anarchists, from the point of view of the Neoist Alliance, the only truthful anarchists). Other texts from this period, both published by the Neoist Alliance as well as by other groups, stressed the close relationship between the thinkers of anarchism and those of proto-fascism, e.g. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

Not all of the Neoist Alliance’s activities would be directed against the anarchists. In proper avant-garde fashion, the canon of culturally-crowned artists was under attack, and it was a performance of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Harlequin at the Pavilion Theater in London that served as the first target. It wasn’t the first time that Stockhausen was targeted. In 1964, a group called the Action Against Cultural Imperialism had picketed one of the composer’s performances, and a decade later, in 1972, Cornelius Cardew had published a work called Stockhausen Serves Imperialism. Stockhausen was seen as the epitome of bourgeois “serious culture”: fashionable nonsense that the ruling class lurked behind to give the air of challenging sophistication. In protest, the Neoist Alliance issued first a press release against the upcoming performance. It claimed that they would levitate the theater over the course of the performance, perhaps a nod to the infamous “levitation of the Pentagon” that was conducted during the March on the Pentagon in 1967, which some of the Motherfuckers took part in.

The event became a spectacle, or at least it appeared that way. As Home’s small band of Neoists gathered before the theater and started their chants, another group led by the Temple ov Psychick Youth (TOPY)—a network of occult-minded, William Burroughs-inspired artists drawn from the ranks of bands like Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV—arrived to prevent the act from taking place. It wasn’t in defense of Stockhausen, however. It was because they suggested that if the theater was levitated, “a negative vortex would be created which could seriously damage the ozone layer.”

“As the handful of individuals who’d decided to cross the picket line arrived for the concert, they were met with chants of ‘Boycott Stockhausen’ from our ranks, to which the TOPY activists replied with cries of ‘Stop The Levitation’. The counter-demonstrators pleaded with concert-goers to remain outside the building so that they could participate in a set of breathing and visualization exercises designed to prevent the levitation. Once the concert began, the two sets of demonstrators prepared themselves for a psychic battle outside the theatre. These street actions drew a far larger crowd than the Ian Stuart recital inside the building. Passers-by were reluctant to step in front of the waves of psychic energy we were generating and soon much of the street was at a standstill. The Brighton and Hove Leader of 20/5/93 quoted one shaken concert-goer as saying, ‘I definitely felt my chair move. It shook for a minute and then stopped.’ The Neoist Alliance also received reports of toilets overflowing and electrical equipment short-circuiting, although these went unreported by the press. While TOPY were adamant that their actions prevented the Pavilion Theatre being raised 25 feet into the air, the Neoist Alliance considers the protest to have been a complete success.”

Magico-Marxian Praxis

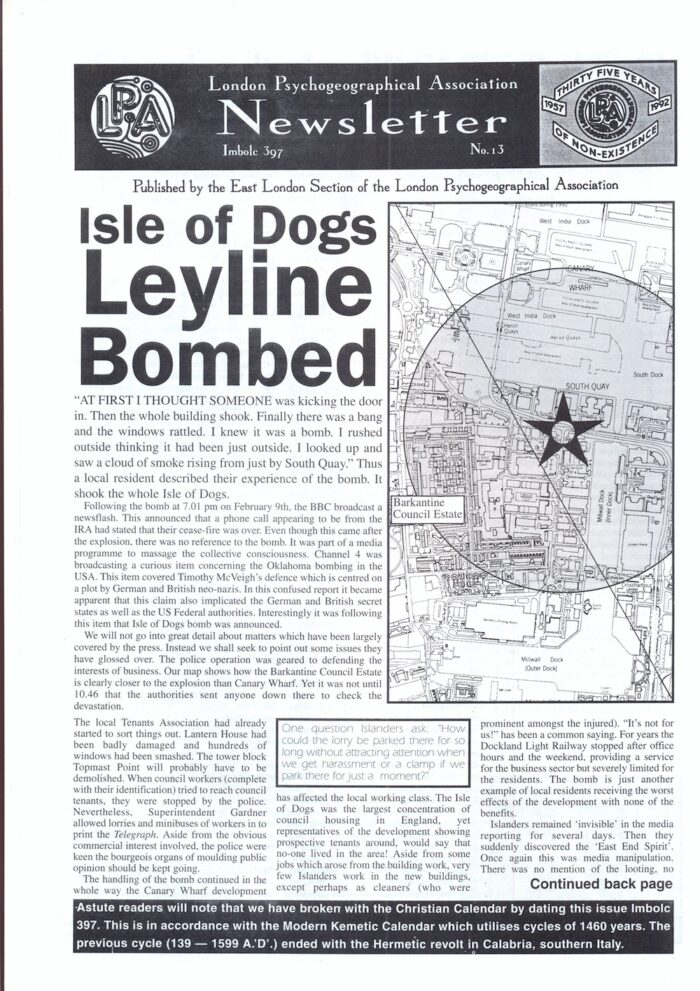

In 1992, another group was revived under new leadership. This time it was the London Psychogeographical Association (LPA). Just as the original outfit had, prior to its merging into the SI, a single member, so did the new one. This singular member was Richard Essex, a pseudonym for Fabian Tompsett, who in a few years time would be one of the driving forces behind Transgression: A Journal of Urban Exploration (as one can imagine, there is considerable overlap to be had between the derive of the Situationists and more recent trends in “urban exploring”). The New LPA, interestingly enough, did not take its cue so much from the first SI, despite the Debordist faction’s heavy emphasis on the environs of the city, but from the Second SI. The shift from town to country, and from Hegelian-inflicted modernism to strange folkways, were part and parcel of the LPA’s repertoire. The agenda was described as “magico-Marxism”, where class analysis collided with investigations of ancient ruins, ley-lines, astrological alignments and long-forgotten sects, secret societies and religions. “Magico-Marxism and its kindred re-enchantments”, as one commentator and Transgressions contributor later elaborated, “combined communist militancy with a romanticization of landscape and memory.”

One example of this Magico-Marxist practice was their rejection of the Gregorian calendar system and the subsequent adoption of one used in early dynastic Egypt. “How can we expect the working classes to take us seriously when we still use the superstitious calendar of the Christians imposed by the bosses?” asked the LPA. For the LPA, the character of domination in the UK—a weird temporality that crossed the seemingly-contradictory currents of bourgeois rule and royalism—was not simply a game of political and economic power. It was also conducted through occult means, a kind of “weaving” that made the fate of the country something determined by the ruling classes. A text titled Who Rules Britain, for example, veers form reflections on income inequality and the chaos of the British parliamentary system to an engagement with Nigel Pennick and Paul Devereux’s book Lines on Landscapes: Leys and Other Occult Enigmas, who they use to argue of the connection between ley-lines and political domination:

“If we trace the roots of the meaning of rule we find ourselves led back to ancient Sanskrit. Nigel Pennick and Paul Devereux discuss this in their book Lines on Landscape: Leys and Other Occult Enigmas… using the work of Jim Kimmis they show how modern words like rule, roi (’king’ in French), Reich (’empire’ in German) etc., are tied to older words such as rex (’king’ in Latin), rig (’king’ in Old Celtic) and also words meaning straight—riht (Old English), reht (Old High German), rectus (Latin). Of course rule and ruler in modern English also denotes drawing a straight line. These roots are also linked to the Hindi word raj, which means ‘rule’.”

To draw this out, the LPA would stage psychogeographical drifts, not strictly in the contours of the urban landscape, as the first SI had, but in places of powerful occultic resonances. One of the first ventures was to a cave in the small town of Royston, England. Known as both Royston’s Cave and Rosie’s Cave, and marked by an old cross monument, it is the topic of numerous local legends that tied it to a variety of different esoteric byways: the cave was used as a ritual chamber for the Knights Templar, the cave was a secret haven for Freemasons to carry out their rights, the Brotherhood of the Rosy Cross (the Rosicrucians) was founded in the cave, so on and so forth.

The psychogeographical expedition to Rosie’s Cave was undertaken during the astrological conjunction of Venus and Jupiter, which harmonized with the goal of unlocking inner occult power systems. A later psychogeographical exploration that aligned with a conjunction included a trip, jointly conducted with the enigmatic Archaeogeodetic Association, to St. Catherine’s Hill in Hampshire, England. An ancient sacred site, St. Catherine’s Hill was the site of a ritual procession, which culminated—at least in the Victorian era, but some suggest more shadowy origins locked deep in the past—in the walking through a labyrinth. The LPA and the Archaeogeodetic Association put together a pamphlet on their voyage titled The Great Conjunction: The Symbols of a College, the Death of a King, and the Maze on the Hill, and also spoke of it in the aforementioned Who Rules Britain text:

“Pennick and Devereux cite the ritual procession of Winchester College up to St. Catherine’s Hill as an example of ‘straight walking traditions’ (see our booklet The Great Conjunction for a more detailed analysis on this), and then speculate as to how the king embodies a ‘supernatural’ power with transmission lines enabling ‘the king’s spirit to radiate out through the kingdom’—maintaining a form of occult rule combining ‘order, power, government, and the Earth Spirit itself’.”

It would be incorrect to see the LPA’s embrace of ley lines and investigations of occult ritual as a flight towards the sort of anti-modern irrationalism castigated by the Neoist Alliance—and indeed, the Neoist Alliance aligned itself with the LPA and embraced magico-Marxism in its own right. In the pages of Re:Action Home recorded the Neoist Alliance’s own experimentation with psychogeographical explorations of ancient mystery sites, and penned essays on the secret occult nature of the ruling class. At times they urged a return to prehistoric Britain as part of an anti-royalist strategy; simply put, such a return wasn’t a desire for primitivism, but a desire for the nomadic character of the island’s ancient population. It constituted the rejection of British identity along the lines of the nation-state, which could only be articulated once the monarchy, divinely instantiated through occult means, arose. As the Alliance wrote in relationship to this mythico-political complex: “The working class has no country. We are ungovernable. Forward to a world without frontiers!”

Similarly, the LPA, despite drawing heavily on their works, castigated ley lines researchers for accepting occultic rule, and thus for implicitly embracing the irrationalism promoted by the bourgeois order. Pennick and Devereux in particular are singled out, despite the ample use made of their work, for “refusing to deal with the clear fact that there can be no move towards harmony without social revolution.” They also attacked ley hunters for their singular reliance on superstitious techniques like cartomancy. This isn’t to say that they disavowed these practices outright—the LPA indeed made ample use of them, but tempered it not only to their Situationist-derived practice of psychogeographical drift, but with computer-aided studies of longitude and latitude. This drew the ire of the ley-line community, and critiques of the group, their peevish preference for the knowingly nonsensical and professedly “modern” outlook, were aired in outlets like Fortean Times. The irony, of course, was that the LPA had effectively baited their opponents into openly embracing exactly what they had been accused: irrationally embracing reactionary, anti-progressive sentiments (something identical, we should note, to the critique of the anarchists in the pages of Re:Action). For all the talk of prehistoric nomadism and theatrical engagement with the occult, groups like the Neoist Alliance and the LPA were ultimately truly modernist.

The Autonomia – Accelerationist Axis

In 1995 Transgressions: A Journal of Urban Exploration was launched by Alastair Bonnett. He was an associate of the LPA, and the the journal itself was deeply embedded in this network: it featured writings of the LPA, and it boasted an editorial board consisting of Stewart Home, Sadie Plant, David Pindar (a Cambridge-based academic with interests in urbanism and urban exploration) and Luther Blissett, among others. Transgressions also brought together the writings from various psychogeographical, urban exploration, and militant “mythopoetic” groups from across Europe. One of these is of immediate interest to us here, and that is a small coterie of self-described “Situationauts” in Bologna (Italy) called the Transmaniacs. It was a project launched by Roberto Bui and Riccardo Paccosi, and it constituted a major intersection of so many strands parsed through in the proceeding pages. As they described the Transmaniacs: “It is a multimedia, subversive project founded in 1992 by a shameless gang of post-anarchists, ex-militants of Autonomia Operaia (Worker’s Autonomy), libertarian communists and underground voyagers of doubtful origin. Our project has gradually dilated and linked alternative radio networks, telematic nets (European Counter Network, Cybernet) and amateurish Bbs, squats, ‘Techno & Western’ combos, theatrical companies, concerts and anti-art exhibits, street riots, unappreciated filmmakers (like Agapito di Pilla), and very ugly magazines and publications.”

In search of a “new revolutionary theory”, the Transmaniacs combined a diverse array of theoretical resources, which were chopped and scrambled and unleashed as a non-linear insurrectionist patchwork: “[t]hey take the writings of Toni Negri, Deleuze and Guattari, Paul Virilio, and Amadeo Bordiga just to let them collide with one another, as theory must be the result of praxis, and originality has never been important.” Like the CCRU, the prehistoric rumblings of which were starting in far away Great Britain, the Transmaniacs’ theoretical offerings fell somewhere between the delirious offerings of zine culture and more academic critical theory; a text by Roberto Bui that debuted in the first issue of Transgressions, called The Coagula, clearly brings together the influence of one of the big inspirations for the CCRU, Mark Downham’s writings in the pages of Vague magazine, with Autonomist theory. It depicts capitalist acceleration as reformatting all socio-political configurations, from the functionality of the state to the experience of time itself. Lodged with one foot in the political and one in the temporal, the city undergoes an immense transformation as well. “The old city is dead”, declares Bui, channeling the old Situationists, before flipping to Baudrillard and Virilio.

“The new tyranny of speed, or Real Time, changes politics and society… bodies are subjected to annihilating accelerations; hi-speed trains imitate the teletransport of science fiction movies, the utopia of transmitting bodies; the megapolis, deranged from immigration and housing problems, dies in a stinking swamp of blood and shit; the experiences of the passer-by are crushed to smithereens under the bombardments of contradictory information and cut’n’confused signs; urban territory loses any recognizability and becomes unintelligible and incomprehensible… the territory implodes along with the society contained by the city itself. The new megapolis is a poisoned microcosm of a whole continent, an interzone of interzones, the exhibition site for conflicts over a territory that doesn’t exist anymore, for the spectacles of a new tribalism fed with the fear of an ‘uprooting’ that has already taken place… the paladins of identity mistake the epilogues for prologues. Some call this Europolis.”

In Europolis, the city is re-organized according to the logic of a new authoritarianism: that of “postmodern architecture”. At this point Bui swerves in hard-nosed post-Autonomist theory, stressing the relationship between the emergence of postmodern architecture and the breakdown of capitalism in its Fordist mode, that is, the intertwining of high mass production with the particular socio-political complex that prevailed in the developed world from the 1910s through the late 1960s. Flexibility, automation, and information services rose in the wake of deindustrialization; these are the hallmarks of post-Fordism. Postmodernism, as Jameson argued, was the cultural logic of late capitalism, which was a concept introduced by Marxist theorist Ernest Mandel to describe a form of capitalism dominated by hyper-fluid financial flows. Late capitalism, in other words, is post-Fordism, and the passage from modernism to post-modernism must be contextualized along the axis of the shift from Fordism to post-Fordism. Bui fleshes this out by making a nod to Downham: “The cities are post-industrialized and have muddled-up class composition… The social sphere has been lacerated by destructuralizations. The Videodrome has taken its place”.

Against the onslaught of these forces, which effectively dissolved the social whilst also reconjuring it as a simulation indistinguishable from reality—hyper-reality, as Baudrillard would say—traditional forces of resistance to capital were eliminated one by one. That isn’t to say that the Transmaniacs veered into defeatism, or believed that the answer to Lenin’s eternal question of “what is to be done?” is simply “nothing.” In many respects, what Bui and his comrades hoped to draw forth was a rigorous theoretical framework for the squatters movement, honing in on the space where it collided with the emergent cyberpunk underbelly of the new world order as the space from which the postmodern metropole could be exploded. In a 1993 piece titled Hold On, I’m Coming, he wrote that:

“The squatting and self-management of a building shouldn’t attempt to restore use-value over exchange-value, but to ignite capital’s territory and open a breach in the city: to open out new ways to free our everyday lives. It won’t be a ‘revalorization’ but the abandonment of the previous sense of a single environment and, at the same time, an adjustment to a new, significant and inclusive space; space which can give to environments a value incommensurable with ‘commodity town’. The squat has to become unusable as capital… The space of self-management should be the first example of unitary urbanism, a microcosm of the city we would like to plan. A place that is alive and alterable. Not merely a political or cultural ‘container’ of initiatives but the initiative itself, forever breaking down its own walls and growing beyond itself. For too long squatters have been mired in their own reassuring customs. It is time to stop the adjustment of initiatives to the environment and start adjusting environments to the initiative. We must start to deconstruct urbanism.”

In their 2004 book Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri pursued the social effects of the transition between Fordism and post-Fordism, modernism and postmodernism, through the work of American sociologist Robert Putnam. For Putnam, there is an ongoing crisis of sociality, as the various means of civic participation and community-building mechanisms—from voter turn-out to bowling clubs, neighborhood associations, various lodges (Elks Lodges and the like), religious organizations, etc.—is undergoing a precipitous decline. This sort of cohesive, socially integrated life was made possible precisely because of the mass industrial system; “Traditional forms of labor, such as factory labor and even more so craft work”, wrote Hardt and Negri, “provided stable employment and a set of skills that allowed workers to develop and take pride in a coherent, lifelong career with a durable social connection centered on their jobs”. As this old industrial order melts away and that social dynamic falls to tatters, the result is nostalgia, a desire for that world (albeit in a properly spectacular image; the ‘golden age of capitalism’ as seen through the lenses of televised representation) returns. Hardt and Negri are prescient on this point—after all, what is the rise of Trumpian populism in America and the new right in Europe but precisely the postmodern politics of nostalgia? They, however, will have done it: “One should do away with all this nostalgia, which when not actually dangerous is at best a sign of defeat. In this sense we are indeed ‘postmodernists’. Looking at our postmodern society, in fact, free from any nostalgia for the modern social bodies that have dissolved or the people that are missing, one can see that what we experience is a kind of social flesh, a flesh that is not a body, a flesh that is common, living substance.”

The Transmaniacs took an identical route. In Riccardo Paccosi’s Strategic Proclamation No. 3, also aired in Transgressions, the project of a “new class war” is proposed in the context of Downhamian Videodromification of the postmodern social order. The task, he suggests, is to forge a line of flight that escapes the bitter nostalgia for the world that is lost, evading both the politics of the melancholic left, which can only ever commit itself to worn-out modes of political experience, and that of the identitarian right. “So we must accept the death of the social sphere as a positive thing” he argues, “and move onto the threshold that enables the dissolution of the new capitalist ecosystem’s dialectical rules.” For Paccosi, this entails the shift from the mass movement to bottom-up, self-organizing process—a clear parallel to the sorts of discourse that was emerging, as we saw in previous chapters, in the cyberculture in other parts of Europe. Likewise, Bui suggests to add the necessity of speed to the picture: in a situation of accelerated temporalities, self-organizing insurgency entails rapid mobility. The capitalist system exacts a nomadic domination, and the struggle against it confronts it on these groups. As Marco Deseriis puts it, “the Transmaniacs formulated a non dialectical theory that maintained that the Spectacle had to be confronted not only from the outside—through a nomadic crossing of yet-to-be-colonized areas of social life—but also from within, through a systematic infiltration and sabotage of the media system.”

Besides participation in hacker and cyberpunk networks like the European Counter Network, organizing within the squatters movement and carrying out LPA-style psychogeographical drifts, the Transmaniacs carried out bizarro pranks and various guerrilla theater stunts. One such event took place in 1994, when the group, joined by another outfit called River Phoenix (named after the young American actor who had died in 1993 as the result of a drug overdose), converged in Bologna to carry out a project they had dubbed “Horrorist Agitation”. To quote Deseriis, “on May 27, 1994, Paccosi simulates a self-gutting in a central street of Bologna by pretending to have spasmodic convulsions and extracting a long veil intestine from underneath his shirt. The performance, which is terminated by the police, is meant ‘to present capitalist society with an anguishing image of itself.’ As one of the editors of River Phoenix points out, ‘Paccosi’s self-gutting is probably the first action that sees the participation, in the guise of fake passersby or authors of outraged letters [to the press], of the core group that will later form the Bolognese cell of the LB Project.’ The horrorist agitation continued with a campaign of fake letters to local newspapers supposedly written by disgruntled citizens to denounce the presence of animal entrails on public buses and in other venues, and then with the actual deployment of such entrails on a bus—an action that obtains some coverage in the local press.”

The “LB Project” referred to by Deseriis here is the Luther Blissett Project. It’s not clear when it occurred exactly, but in the wake of the Horrorist Agitation series both River Phoenix and the Transmaniacs mutually dissolved themselves and continued under the rubric of the Project. It would be incorrect to read into this a sharp break or rupture of any kind; there exists a direct line of continuity between the aims of the Luther Blissett Project and the earlier activities of the Transmaniacs and their expanded networks. There was a professed goal shared by each: the ludic subversion of postmodern capitalism via a revolution carried out like a viral infection, a delirious infestation that would spread through the cybernetic relays that constitute the imperceptible infrastructures of our virtualized world.

Legion

In her book The Emergence of Social Space, Kristin Ross draws attention to the way Arthur Rimbaud’s loving depiction of the Communards of 1871 is a poetic invocation of the rebelling people as a swarm. Like a great cloud of insects the masses rise up, seemingly leaderless, and overrun all pretenses of sovereign power that seeks to control their movements. The description brings to mind the Nietzschean “swarming-out” that we discussed in the previous chapter, and indeed Ross openly borrows from Nietzsche to flesh out her analysis. Just as Nietzsche perceived this form of insurrection as breaking the stranglehold that older types of mass politics had on revolutionary action, Rimbaud’s swarm presents a new articulation of the way the dispossessed rise to the level of class struggle. For Hardt and Negri, however, the identification of the swarm and the Communard revolt was premature, or perhaps more fittingly, a premonition of the struggles-to-come. Instead of situating the locus of the swarm in early days of the Third Republic, they move it to the present moment—the swarm as the form that politics necessarily takes under the condition of postmodernity. Taking note of the interest in highly non-linear insect behavior shown by artificial intelligence researchers and computer scientists, they describe how “[t]he intelligence of the swarm is based fundamentally on communication”, or, in other words, on the very logic that is at the center of post-industrial capitalism. They continue: “The swarm model suggested by animal societies and developed by these researchers assumes that each of the agents or particles in the swarm is effectively the same and on its own not very creative. The swarms that we see emerging in the new network political organizations, in contrast, are composed of a multitude of different creative agents. This adds several more layers of complexity to the model. The members of the multitude do not have to become the same or renounce their creativity in order to communicate and cooperate with each other. They remain different in terms of race, sex, sexuality, and so forth. What we need to understand, then, is the collective intelligence that can emerge from the communication and cooperation of such a varied multiplicity… This is a new kind of intelligence, a collective intelligence, a swarm intelligence, that Rimbaud and the Communards anticipated.”

Or, as the CCRU put it in their text Swarmachines: “the space-time of hypercommoditization is a nomoid zone of mad clusters where the polis disintegrates into unintelligible webs of swar machinery. Schizophrenic capitalism: cultures without a society, a mutant topology of unanticipated connections[.] Be hivelocity and if you think it’s gonna blow….you haven’t seen anything yet.” The swarm is an anonymous force, appearing to sovereign power as a political impossibility (“In an ordered society, the insectoid buzz of heterodoxy must always and already appear as a nightmare”). The swarm is radically deindividualized; while its totality is an aggregate of single elements, it strips out the particularities in exchange for open-ended flux. It has, in other words, no face, precisely like the Panther Moderns of Gibson’s Neuromancer, which as we’ve seen so far, influenced the Critical Art Ensemble. Postmodernity melts down identity, post-industrialization scraps the residual traces of the organic body—and before the control matrix can substitute a simulated identity, holographic organicism, the swarmachine makes a break outwards, pursuing what can only be described as a ‘non-dialectical opposition’.

How do you fight a simulation? By overrunning its circuitry and by feeding it back to itself.

The origins of the Luther Blissett Project are shrouded in mystery, but there are several interlocking accounts that allow us to narrow it to a small group of individuals in Italy. It seemed that the primary culprits were Vittore Baroni and Piermario Ciani, a pair of mail artists who were connected with neoist circles and the underground squatting scene. Taking cue from the neoist’s use of Monty Cantsin, and Home’s introduction of Karen Eliot, Baroni and Ciani made ample use of the open name strategy. In the early 1980s, for example, they “launched Trax, a collaborative mail art project consisting of the distributed co-production and exchange, via the postal system, of various materials, mostly sound collages. Participants in the project adopted a serial name (Trax 01, Trax 02)…” After the Trax experiment came Mind Invaders, a “fiction punk band whose concerts, releases, reviews, interviews, and subsequent disavowals were entirely fabricated by an extended network of music journalists.” Mind Invaders would later be the title of a book (well, two, if we count Stewart Home’s 1997 anthology of this writings from the British corner of this network) attributed to Luther Blissett, which covered the first “phase” of the project.

Mind Invaders suggested that Ray Johnson himself had been involved in the Luther Blissett Project (henceforth LBP). A subsequent text titled Ray Johnson: A Zapatista in Greenwich, itself attributed to Luther Blissett, set the record straight (or straightened it just a little; it sheds no light on who launched the LBP). It returns again to Baroni, who recounts that in a letter Johnson had asked who Luther Blissett was—the answer being, of course, that he was a Jamaican-born footballer who had played in England before being traded to Milan. His career in Milan had been something of a flop, and a persistent rumor was that Blissett had been traded by mistake, and that it was his teammate John Barnes that Milan was interested in. Amused by the story, Baroni forwarded Johnson’s letter to Stewart Home. Shortly thereafter, a psychographic drift by the Neoist Alliance and the LPA happened across a byway called Blissett Street, which apparently was named for the little-known George Blissett, “a Victorian do-gooder”. Thus, Ray Johnson wasn’t personally involved in the project, but had nonetheless managed to help give rise, in a roundabout and appropriately non-linear manner, to it.

The LBP constituted, in many respects, a deeper radicalization of the uses of Monty Cantsin and Karen Eliot. While the previous open names had been deployed towards certain political ends (Monty Cantsin as a critique of artistic individualism, Karen Eliot in relation to the Art Strike), Luther Blissett was planted firmly in the line that stretched through groups like the Transmaniacs and the Decoder collective back to the Movement of 77. The emphasis that the Transmaniacs gave to the experience of post-industrialization, and the problems—and openings—it confronted anti-capitalist resistance with was continued under the auspices of the LBP. Luther Blissett would later appear in the pages of Multitudes, a French journal dedicated to post-Autonomist theory, where the project was described as having been launched by “a group of young Bolognese from post-workerist backgrounds.”

Whoever they were, the LBP erupted with a bang. In the project’s opening communiqué, the opening line declared “At this moment the Luther Blissett Multiple Name Project has been joined by dozens of mail-artists, underground reviews, poets, performers and squatters’ collectives in some of the main European cities.” Information was also provided on how to find information about Luther Blissett activities in the United States (the contact information, incidentally, was San Francisco-based mail artist Mike Dyar, who had been involved in the run-up to the Art Strike several years prior), along with brief reports on actions that had already been carried out (such as letters sent by Luther Blissett to Fidel Castro). The communique also makes mention of a program on Radio Città del Capo, a radio station with ties to the Italian far-left, hosted by Luther Blissett that would feature “psychogeographical reconnaissance of the city from midnight to daybreak.”

A text published shortly after the initial communique named some of the important influences on the project, titled Guy Debord is Really Dead, lampooned the self-declared Situationist leader and eulogized him as “Guy the Bore”. In place of the usual Situationist historiography, Luther Blissett offered a “counter-history” that opted instead for the activities of Gruppe SPUR and the Second SI:

“The role of the 2nd SI and of the other expelled members has been underestimated and ignored for a long time. Especially in Italy, nobody knows much about it. Apparently the excommunication still has a strong influence and the francocentric perspective is still operating. Soon after the split, both the SIs kept on promoting scandals as a political weapon. But, while the Strasburgh scandal (a fucking stroke of luck which was very well exploited and propagandized) gave the Paris-based one a thrust which allowed them to wash their bollocks in the 1968 agitations, the other couldn’t go further what today we would call a ‘kreative’ approach and slowly imploded. And yet it had an indirect influence on the 68 movement both in Europe and all over the world, as well as many of the other ex-members did. Dieter Kunzelmann, former member of SPUR and contributor of Situationist Times, helped to found the Kommune 1 in West Berlin; the Kommune 1 appealed lots of young people, challenged the marxist-leninist positions of the SDS and contributed to give that organisation -and the whole German movement- anti-authoritarian connotations. Some years earlier the Dutch former member of the SI, Constant (the one Debord most derided, sometimes rightly), had an important role in the crucial PROVO movement in Amsterdam (1965-67): before being recuperated by the omnivorous institutions of that town, this movement offered the worldwide counterculture efficient and unpredictable ways of action. In London, King Mob issued several pamphlets and a tabloid paper (King Mob Echo) and provoked many events: for instance they caused street riots giving out fake news to the papers or expropriated department stores disguised as squads of Santa Clauses. Malcolm McLaren was a fan of King Mob: he would exploit Punk showing he had learned the Strasburg lesson, in all its positive and negative features. Thanks to this influence McLaren and Jamie Reid (the Sex Pistols art director) ‘they refined the taste for for new practices of communication—manifestos, leaflets, collages, pranks, wrong information—which gave a growing feeling that the state of things could be shaken, if not irreversibly transformed’.”

More writings poured in over the following years, more and more diverse and polyphonic as different individuals and groups picked up the name and made their own work out of it. In England, the LPA organized the Luther Blissett Three-Sided Football League, producing a new connection between the real-life Luther Blissett and Asger Jorn’s triolectical thought experiments. There was the Viterbo Satanic panic hoax, which we’ve already discussed at the outset of this chapter, but before this was the so-called “Ralph Rumney’s Revenge” in 1995, named for the original founder of the London Psychogeographical Association. It was an act of “psychogeographical warfare” waged against the course of the Venice Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary Arts, which Luther Blissett condemned on the grounds that it served as a machine for the recuperation of the avant-garde—a function that arose precisely because the city had been the target of various avant-gardes throughout modernity. The opening salvo in this insurgency/apparatus of capture technique had been fired with Marinetti’s futurist screed “Let’s Murder the Moonlight” and his relentless attack on museums and cultural recollection as worthless sentimentalism. Now, on the far side of the century, Luther Blissett was going to finish the smashing that Marinetti and his rowdy cohort had begun. The city’s streets, alleys and byways were plastered with stickers and posters directing people to the “Luther Blissett Way”. It was designed to induce a spontaneous psychogeographical ambling: Luther Blissett Way was a destination that was immanent to the whole process, as the meandering directions transformed Venice into a labyrinth (it’s not clear, however, how many participated in the drift). In another instance, the Bologna-based Luther Blissett Situationautic Theatre—a group that had grown directly from the Transmaniacs—attempted to infiltrate the hotel where Princess Diana was staying, disguised as fans. It was a joint action with the LPA, which as we saw earlier was joined with the Neoist Alliance in a schizo-revolt against the British monarchy. Inside the hotel walls, the group would then disseminate anti-royalist propaganda developed by the LPA—but as with the drift, it’s not clear the degree to which this intervention was successful.

In spring of 1995, a new “Radio Blissett” sprung up in Rome. It’s activities went a little further than its Bologna-based counterpart, a indicated by one Luther Blissett communique: “[it was] broadcasted on Saturday night, thus the events took place in more crowded places, either at illegal raves or in the eternal traffic jam of a big, violent city. Luther’s actions and psychic attacks resulted in fascist aggressions, riots and psychogeographers under arrest”. On June 4th, for example, a “psychic attack” was staged as part of a anti-work demonstration in front of Rome’s General Employment Agency, and a week later, thirty people attempted to stage a “Massive Psycho-Sexual Intercourse” before the Immacolata Concezione (the gaggle of lovers, wrapped in cellophane, were broken up by the cops before it could progress very far). Then there was the infamous “rolling rave” incident:

“On June 17th at 2:10 a listener called the studio and suggested occupying and diverting a night bus. Luther chose the line no.30 and exhorted the audience to gather at a bus stop in Piazza del Verano. At 2:55 Luther took possession of the bus with drums, confetti, drinks and ghetto blasters tuned on Radio Blissett. The diverters bought only one ticket, because they all shared the same open identity, that of Luther Blissett. Joyful people, informed by the radio, came aboard at any stop. The driver was not as happy. Luther was in touch with the studio by a cellular phone. At 3:15 a police block forced the bus to stop in Piazza Ungheria. The feast-lovers descended and, 15 minutes later, occupied another bus on the line no.29. The cops stopped the bus again in via Guido d’Arezzo. Since the psychogeographers refused to surrender, they were assaulted by the cops and beaten with truncheons. Luther did not bear all that without reacting, and an officer was injured. At that point, a cop shot three times up in the air. The riot and the shoot-out were picked up by Luther’s phone, heard in the studio and broadcasted. About 10 Luthers were taken to the police station, where they were charged with ‘seditious rally’ and ‘outrage, resistance and aggression to public officers’.”

A later write-up of the incident described the various Blissett’s goals as making “a full immersion of bodies in the dense net of the communication fluxes, those of the urban, technological and mediatic planes. This in order to redefine the space in a creative way, and to reconfigure the public bus as a location for extraordinary events, beyond the border of the everyday forced mobility.” Deseriis points out that in the wake of this incident, the wider militant left—which had viewed the LBP as an “intellectual gizmo for wannabe radicals rather than as serious activism”—came to see the growing swarm as “an organic component of the movement, in particular of its anarchist-nomadic wing.” This politicization can also be seen in Luther Blissett’s “Declaration of Rights”, drafted by the Rome-based section of the project under the influence of the post-Autonomist theory of Sergio Bologna and Christian Marazzi. For Bologna and Marazzi, post-Fordist capitalism was characterized by the detachment of productivity and wage growth, which not only engendered dangerous imbalances in the economy (raising the specter not only of the classic Marxian problem of overproduction, but of underconsumption as well), but acted as a blockage for anti-capitalist activities. Thus they came to pose the need for a kind of guaranteed citizen’s income (echoed by Hardt and Negri in Empire, where they referred to the “social wage and a guaranteed income for all” as a concrete political demand capable of being made by the multitude, their post-Marxian term for the swarm-entity that the postmodern underclasses could become). In the “Declarations of Rights”, this demand is precisely what is taken up:

“The industry of the integrated spectacle and immaterial command owes me money. I will not come to terms with it until I will have what is owed to me. For all the times I appeared on TV, films, and on the radio as a casual passerby or as an element of the landscape, and my image has not been compensated . . . for all the words or expressions of high communicative impact I have coined in peripheral cafes, squares, street corners, and social centers that became powerful advertising jingles . . . without seeing a dime; for all the times my name and my personal data have been put to work for free by statistics for adjusting the demand, refining marketing strategies, increasing the productivity of firms to which I could not be more indifferent; for all the advertising I continuously make by wearing branded T-shirts, backpacks, socks, jackets, bathing suits, towels, without my body being remunerated as a commercial billboard; for all of this and much more, the industry of the integrated spectacle owes me money. I understand it may be difficult to calculate how much they owe me as an individual. But this is not necessary at all, because I am Luther Blissett, the multiple [multiplo] and the manifold [molteplice]. And what the industry of the integrated spectacle owes me, it is owed to the many that I am, and is owed to me because I am many. From this viewpoint, we can agree on a generalized compensation. You will not have peace until I will have the money! lots of money because I am many: citizen income for Luther Blissett!”

Cybernetic Insurgency

At some point Luther Blissett entered into a collaboration with several German activist-theories, Sonja Brunzels and the elusive autonome a.f.r.i.k.a gruppe, which resulted in a series of writings that put forth the theory of the communication guerrilla. It’s something of a grand theory of what exactly the politicized open-name program was up to. In What about the Communication Guerrilla, for example, we read that the goal of the communication guerrilla isn’t to “occupy, interrupt, or destroy the dominant channels of communication.” Instead, the insurgent sought to “detourn and subvert the messages transported.” Inducing a satanic panic in Viterbo is a brilliant example of precisely this, having hijacked the communicative relays of the simulation and used them to intensity hysteria for events that weren’t even occurring. But as we’ve seen, this was just one of many instances—and there were more still to come.

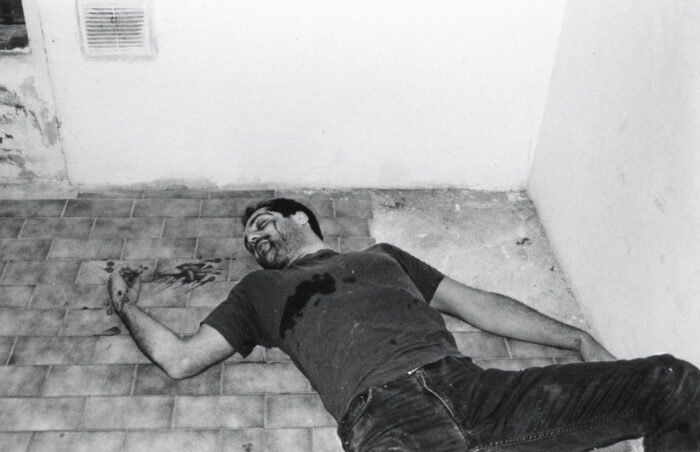

Between 1991 and 1992 a series of alleged murders occurred along the coast of Croatia. Upon investigating the reports, the police discovered not butchered bodies but, oddly enough, dismembered mannequins. The incidents seemed to die off, but after a brief lull they returned again and again, even as the region came to be rocked by the civil unrest and outright conflict that characterized the turbulence of the post-Soviet epoch. Fast forward to 1997, and the Italian-based Free Art Campaign makes the claim that the gruesome stagings were part of an ongoing performance art experiment being carried out by an artist by the name of Darko Maver. Furthermore, they reported that Maver had in fact been arrested in Kosovo—a nugget of information simultaneously preventing contact with him that also served as a lure for the drama-inclined art world. At the same time, a gallery in Ljubljana held a retrospective on Maver. The exhibition presented photographs of the Croatian scenes as well as new, previously unknown arts, some of which were astoundingly macabre (“photos of hyper-realistic fetuses and abortions made of wax and plastic”).

Darko Maver found dead in April 1999. Photo via 0100101110101101.ORG

In 1999, it was announced that not only had Maver been arrested again in Kosovo, but had actually been found dead in his prison cell. According to the Free Art Campaign, suspicions of foul play abounded: “the official version states that his is a suicide; the suspect that Maver was summarily executed is doomed to stay. We are eye-witnesses of another uncounted crime.” Art journals and the international press seized on the stories, and as calls for justice rang out the “thought reflections” of the art world started to emerge. Analyses of Maver’s violent and macabre art works were seen as being a mirror held up the violence of his time and place. Maybe the thoughtful staging of bloody, butchered mannequins was a commentary on the way that the Western media cynically used images of violence against civilian populations as propaganda for militarized intervention. But then,

“On February 6,2000,a press release entitled The Great Art Swindle co-signed by Luther Blissett and 0100101110101101.ORG, reveals that the entire Free Art Campaign has been orchestrated by a network of artists and activists operating in Bologna, Rome, and Ljubljana. The life and death of Darko Maver were a pure invention, a myth designed to expose the mechanisms by which the art system thrives and replicates itself… The press release went further to describe the swindle as ‘an active riot’ against the ‘capitalist art system’, responsible for commodifying any creative act and even life itself. This was a risk that Darko Maver did not run because ‘Darko Maver doesn’t exist!’ as he is himself ‘an essay of pure mythopoesis’, a virus designed to infiltrate the art world and release his potential from within.”

0100101110101101.ORG was the moniker of Eva and Franco Mattes, two New York City-based artists whose first project had entailed stealing all sorts of minor artifacts from famous art pieces—some worn fabric from Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, a bit off the side of Duchamp’s urinal, etc—which were displayed under the name, fittingly, of “Stolen Pieces”. They were also known for their involvement in net.art, or more properly their attempts to radicalize net.art, which they viewed as passive abstraction that fell far short of real participation and interconnectivity.

The Luther Blissett that 0100101110101101.ORG had embarked on the Darko Maver project, meanwhile, was something of a “second generation” of the project. In 1999, ahead of the unveiling of the Great Art Swindle, the LBJ announced the conclusion of the project itself in an act of collective “Seppuku”. A communique dated September 6th, 1999 made it clear that while the project was closing down, this was by no mean the end of Luther Blissett: “Many subjectivities of the Luther Blissett Project Italian columns have decided to greet the new millennium by committing seppuku, a ritual suicide. We are not advocating nihilism or relinquishment; rather, we are choosing life. Seppuku is not *the* course of action, Luther Blissett is a name that anybody can keep adopting also after next New year’s Day. There are countries where the fight has just begun, and we surely hope it goes on. Seppuku is our suggestion for those who have used the name for at least the past five years, so that they look for new styles of this martial art, and let the ‘newcomers’ free to develop their own plans. We should be strangers in nameless lands: to someone else, this can be accomplished by adopting the LB multi-use name; to us ‘veterans’, it is quite the opposite.”

The same year as the seppuku, the Bolognese faction of the LBP—Roberto Bui (of the Transmaniacs), Giovanni Cattabriga (an editor for River Phoenix), Luca Di Meo, Federico Gugliemi (another editor for River Phoenix), and Riccardo Pedrini—collectively published the historical fiction novel Q. Set during the Counter-Reformation period and depicting the zig-zagging conflict between a nameless narrator and his opponent, the titular Q, a Vatican spy whose task is to infiltrate and disrupt various Protestant insurgencies. There’s considerable debate over the novel’s meaning—is it an allegory for the struggle against neoliberal globalization, which was well under way at the turn of millennium, or was it a coded history of the Luther Blissett Project itself? At any rate, Q was the first of a series of literary experiments that blended high-brow historical fiction with pulp attributes and suggestive political overtones; in 2000, the ex-Luther Blissetts reformed as the collective group Wu Ming. In 2002, they released 54, something of a highly complex spy novel set in the year 1954, and two years later they co-authored the script for the film Radio Alice, a quasi-fictional take on the Mao-Dadaist wing of the Autonomist movement. Since then, two more collectively-penned novels have followed (Manituana in 2007 and Altai in 2009), and solo novels by each member of the collective have been penned. Perhaps as a callback to the Baroni and Ciani’s Trax project, the authorship of these individual novels is attributed to a successions of Wu Mings: Wu Ming 1 (Roberto Bui), Wu Ming 2 (Giovanni Cattabriga), Wu Ming 3 (Luca Di Meo), Federico Guglielmi (Wu Ming 4) and Riccardo Pedrini (Wu Ming 5).

Other groups look equally interesting routes outside of the Luther Blissett moniker. One small faction re-organized as the Men in Red (MIR), a “Marxist UFO group” whose name was a play on the Men in Black, those classic figures of conspiracy lore that are associated with, if not a covert agency of the US federal government, a more sinister and occulted entity. Their goal of raising class consciousness in the UFOlogy community was directly influenced by the Posadists, a faction in the Fourth International centered around the strange ideas of Argentinian Trotskyite Juan Posadas. Posadas drove the Marxist position on technological development to its surreal conclusions: if advanced technology flourishes in the stage beyond capitalism (an argument overtly staged by Marx in Notebook VII of the Grundrisse), then a space-faring civilization must be communist. Thus “the goal of the party… should be to establish contact with the communist space aliens, who would take part in furthering the revolution on this planet.” While the Posadists were utterly serious (they urged immediate nuclear war, for example, to speed-up the intervention of the aliens), the MIR blended scholarly UFOlogy, a general interest in technological development, and Luther Blissett-style playfulness and irony. The following, from their key text Radical UFOlogy, is a good example of this heady stew:

“In the historical intersection of the 1950s, the form dismantles those obsolete institutions that have become obstructed by its global extension. So the work, contained until then within the perimeter of the factory institution, is in a sense ‘liberated’ and extended. It is no longer the time limited by a contract but the entirety of the time of life. The ‘archaeologist of power’ Michel Foucault dedicated much of his analysis to the correlation between spatiality and domain production. In his last writings he mentions the need to push beyond the analysis on the genealogy of power, interpreting as paradigmatically innovative the signals coming from the new forms assumed by the contemporary social relationships. On the same interpretative line Gilles Deleuze proposed an interpretative model of social relations based on the progressive elimination of all mediation between the flows of power and the biological community… The premises for this transformation are rooted in the distant past of the American continent. In 1948, just one year after the famous case Kenneth Arnold and in conjunction with the Mantell and Gorman cases, the World Federation for Mental Health was founded, officially a non-governmental organization. A real task force for monitoring and intervention in high-risk areas of violation of terrestrial sensoriality… These studies will give birth to the famous MK-Ultra project for the study and experimentation of ‘psychological warfare’ techniques such as brainwashing… In this view of restructuring in the cognitive sense of capital only sporadically, military violence found a reason for intervention. The conflicting aspects were foreseen and sedated according to strategies peculiar to the most elaborate techniques of conditioning the masses. This process will be perfected to the present day, becoming a reality in what Gilles Deleuze called ‘control society’, as opposed to the societies involved in the repression and detention of the body investigated by Michel Foucault as a ‘society of discipline’.”

A number of elements freely collide: the transition from Fordism to post-Fordism, which as we’ve seen entailed the transformation of modernism into postmodernism, is further coupled to the passage, detected by Gilles Deleuze in one his final texts, from the “disciplinary society” of Foucault to a new network-oriented, ever-changing “control society” (the parallels with the passage charted by Downham are clear). This is the same argument that is made by Hardt and Negri Empire (which after all was ultimately a summation of the major trends of post-Autonomist thought): “The establishment of a global society of control that smooths over the striae of national boundaries goes hand in hand with the realization of the world market and the real subsumption of global society under capital”. What is present in the MIR’s account, however, is the element of subterfuge: the slow creep of military technologies, particularly those that penetrate the deepest folds of matter where subjectivity itself is produced. As Downham said in his Vague piece Cyberpunk: “No-one should forget the nihilistic synergism between the development of cybernetics and military requirements, because waiting in the wings are the multi-nationals.”

Deleuze, meanwhile, was by 1990 already offering suggestions as to the nature of future conflict that would fall very closely to the activities of the information guerrillas, this great anonymous swarm. As he stated in an interview with Negri: “It’s true that, even before control societies are fully in place, forms of delinquency or resistance (two different things) are also appearing. Computer piracy and viruses, for example, will replace strikes and what the nineteenth century called ‘sabotage’ (‘clogging’ the machinery)… Maybe speech and communication have been corrupted. They’re thoroughly permeated by money—and not by accident but by their very nature. We’ve got to hijack speech. Creating has always been something different from communicating. The key thing may be to create vacuoles of non-communication, circuit breakers, so we can elude control.”

Space is the Place

In 1969, Eduardo Rothe wrote a text called The Conquest of Space in the Time of Power for the twelfth issue of the Internationale Situationniste. Commenting on the capitalist nature of the space race, it looks towards the possibility of a freely operating, technologically-literate population that realizes the movement to the stars in a way that is beyond the injurious conditions of the (then) present. Rothe ends his meditation on a note, a promethean proclamation: “Humanity will enter into space to make the universe the playground of the last revolt: the revolt that will go against the limitations imposed by nature. Once the walls have been smashed that now separate people from science, the conquest of space will no longer be an economic or military ‘promotional’ gimmick, but the blossoming of human freedoms and fulfillments, attained by a race of gods. We will not enter into space as employees of an astronautic administration or as ‘volunteers’ of a state project, but as masters without slaves reviewing their domains: the entire universe pillaged for the workers councils.”

Nearly three decades later, in 1995, this desire was rekindled by a loose network, formed in Great Britain but which would soon become global in scope, called the Association for Autonomous Astronauts (AAA). Like the Luther Blissett Project and the CCRU the AAA was engaged in mythopoeosis/hyperstitional alchemy in order to induce resistance to post-Fordist capitalism and open up radically new futures. “We are not interested in going to space to be a vanguard of the coming revolution” they declared; “the AAA means to institute a science fiction of the present that can above all be an instrument of conflictuality and radical antagonism.” The basis for the promotion of this “science fiction” was a Five Year Plan, clearly inspired by the rapid industrialization programs of the Soviet Union, that consisted of “building a network of local, community-based groups dedicated to building their own spaceships.”

Each year of the plan saw the issuing of a special report dedicated to recounting the various activities of the AAA network, all of which were clustered around certain overarching agendas. An early phase announced in the AAA’s Second Annual Report was, for example Dreamtime (which would later be used also to define the period after the conclusion of the Five Year Plan, but prior to the actualization of autonomous space-faring societies), which they defined as “a transversalist concept which helps to define the AAA’s total opposition to existing space programs.” Part and parcel of this was the declaration of an “information war” against the world governments and their various space agencies. For the AAA, organizations like NASA were effectively military organizations: they had emerged in the wake of the Second World War (often as a result of nefarious activities, such as the CIA’s Operation Paperclip), and were then intimately interwoven with the bids for global supremacy that characterized the Cold War. In the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, antagonism to the post-Fordist capitalist order ceased to exist. The march towards transnational domination had been achieved, but there were implications that radiated beyond the thin envelope of the earth’s atmosphere. The stage was primed for the domination of space through its colonization of capital. Speaking of their rejection of plans to transform Mars from a dead planet to a living planet, the AAA wrote that “terraforming will be the action of a capitalist system that, out of control, has exhausted the earth’s resources and requires another planet to devour.”

Thus the goal of getting to space was not only profoundly political—it was a revolutionary task, which was articulated with shades of Posadism: “the AAA happily declares itself to be in league with aliens and that we plan not only to destroy the state, corporate, and military monopoly of spaceships, but also to obliterate human civilization.” In search of a radical means of obliteration, a tactic of “going several directions” at once was advanced, in which the complex myth of the AAA, which could be assembled in accordance with however a given group intended, could be pushed into a variety of different domains. Sometimes it inclined more towards activism, with protests staged during space probe launches and at the headquarters of government-subsidized aerospace firms. Detournement was also pursued; mass culture, the AAA noted in their Third Annual Report, was inundated with fantasies of outer space, manifesting in everything from the popularity of Toy Story’s Buzz Lightyear to Star Wars. Tuning this latent desire to the correct channel and the higher imaginal coordinates could be locked into. It would be worthless, however, without a sense of scientific literacy, so various AAA factions pursued DIY science in search of a way to bring the high conceptualization that was seemingly the sole purview of the military-industrial complex down into a dynamic and creative populist matrix.

It goes without saying that the AAA was deeply enmeshed in the strange contours, this Eternal Network, that we’ve been lightly tracing. As mentioned several chapters back, the AAA had a presence at the Dead by Dawn parties and was featured in the pages of Datacide. It was an avid promoter of the concept of the three-sided football (some of the network’s communiques stress the necessity of applying Jorn’s triolectics to the construction of spacecraft) and was involved in the expansion of the LPA’s Three-Sided Football League. Membership in the AAA was fueled by groups aligned with the LPA, with a recent retrospective naming the London Institute of Pataphysics and the Workshop for Nonlinear Architecture in Particular. The former was a surrealist organization dedicated to promoting Alfred Jarry’s hyper-metaphysical science, and the another psychogeographical group based in London and Glasgow (sadly, information on both groups is incredibly scarce). It goes without saying that Luther Blissett too was deeply involved in the AAA. Communiques bearing his name are scattered through the annual reports; perusing through them, one is treated to everything from Luther Blissett’s reflections on sex in space to summations of annual AAA conferences. The first of these, incidentally, was held at the Public NetBase in Vienna, and then second one was brought closer to Luther’s “home territory”—Bologna, Italy.

The events over the course of the second conference opened up the relationship between the AAA and other groups with similar intentions, and helped them flesh out the nuances of their position and how it operated politically. Antagonism arose when members of the aforementioned Men in Red. In the course of a talk on “joining with aliens to demolish capitalism”, they began to fire potshots at the AAA for their “supposed escapism and reformism.” The AAA, in turn, could only view the MIR as playing the worn-out games of yesteryear’s politics: “The Men In Red, like all politicos, want us to stay firmly on planet earth until the time is ‘right’. In this they are exactly the same as state agencies like the church (who wants us to behave until we get to ‘heaven’), government (who needs us to pay taxes), or army (who wants us to spectate as they destroy not only this planet, but also the rest of the galaxy). In astronomy, a revolution is what occurs when an object returns to its point of origin. Back to square one. The AAA is not content with the rhetoric of the past. We wish to move beyond it, into an arena where everything is possible, where we move in several directions at once to create a life based on possibilities rather than constrictions. As part of this process we expect to develop new ways of social interaction that will suppress capitalist relations.

One of MIR’s problems is that they treat the AAA as a single thing. If we were some kind of cult where everyone shared exactly the same sort of viewpoint this might be a worthwhile pursuit (it works with a lot of other groups). However, the AAA revels in contradiction and a diversity of trajectories. To accuse us of escapism is missing the point entirely. There are far too many people on this planet pissing their lives away waiting for the ‘glorious day’ or dreaming up new ideological straitjackets that prevent them from opening even their front door. That, for us, is the real escapism. We offer a practical way forward. We would like to make it clear that it isn’t our intention to zip off into space to form some kind of hippie dropout commune. Our trajectories must be open to all. Our message to the Men In Red remains: Revolutionaries, one more effort to become autonomous astronauts!”

This wasn’t to say that the AAA were anarchists (even if they had anarchists in their ranks); in the Second Annual Report, drafted in 1997, the AAA took issue with the anarchists who criticized them for “advocating the out-of-body experimentation as part of our investigation into new concepts of space.” The condemnation recalled the critique made of anarchists by the Neoist Alliance: they were, in the AAA’s eyes, far-too backwards glancing and locked into sentimentalism. “These cretins cannot understand how it has become possible for us to destroy the old Gnostic concept of a division between inner (mental) space and (physical) outer space. Behind their nostalgic tales of squatting buildings and fighting the cops, is a self-righteous belief in the sanctity of the body and in what they describe as an ‘authentic’ experience.” Against the longing for organic totality, the great-swarming out lurks under the playful rhetoric and surrealist imagery drawn forth by the AAA. Marxian at their core, for the AAA the flight to space and the cultural mutations that occurred along the way were indexes of a synthetic progress. It was not simply another postmodern spectacle, but something that aimed to both overcome the spectacle and postmodernity, to return to the possibility of some higher stage.

Despite all of this, however, the AAA was often accused of being little more than “pomo pranksters” by the public, but also particularly by more “serious” political actors. There is thus a parallel with Luther Blissett who was viewed with suspicion by the more mainstream factions of the far left. But just as the infamous “night bus incident” established the political bonafides of the Luther Blissett Project, the AAA underwent its own transformation during its “Ten Days that Shook the Universe” program in London. As one retrospective describes, “while in many ways similar to its Intergalactic Conference precursors, the ‘10 Days’ gathering was markedly more political in nature. It was at this gathering for consolidation that the Autonomous Astronauts marched on Lockheed Martin’s headquarters in London, calling for an end to the militarization of space, something which ultimately gave this whimsical group of artists a far more political veneer.”

“I think the ‘10 days that shook the universe’ established the AAA as a social movement, in the style of ‘Reclaim the Streets’ (another movement popular at that time in London) but addressed to astra,” Riccardo Balli of AAA Bologna told me in an email. “So for ‘10 Days’ it was ‘Reclaim the Stars!’”