Among the Shadows of Karakoz

Mai Mai Mai in front of Wonder Cabinet. Photo Sofia Lambrou.

Karakoz is Mai Mai Mai’s new album. It will be released on February 6th via Maple Death Records, together with Radio alHara and Wonder Cabinet. The following contributions are also included in the album’s booklet, but we are very happy to present it here as well, as a preview and integral part of the path that accompanies the making of Karakoz, as recounted in Toni Cutrone’s introduction.

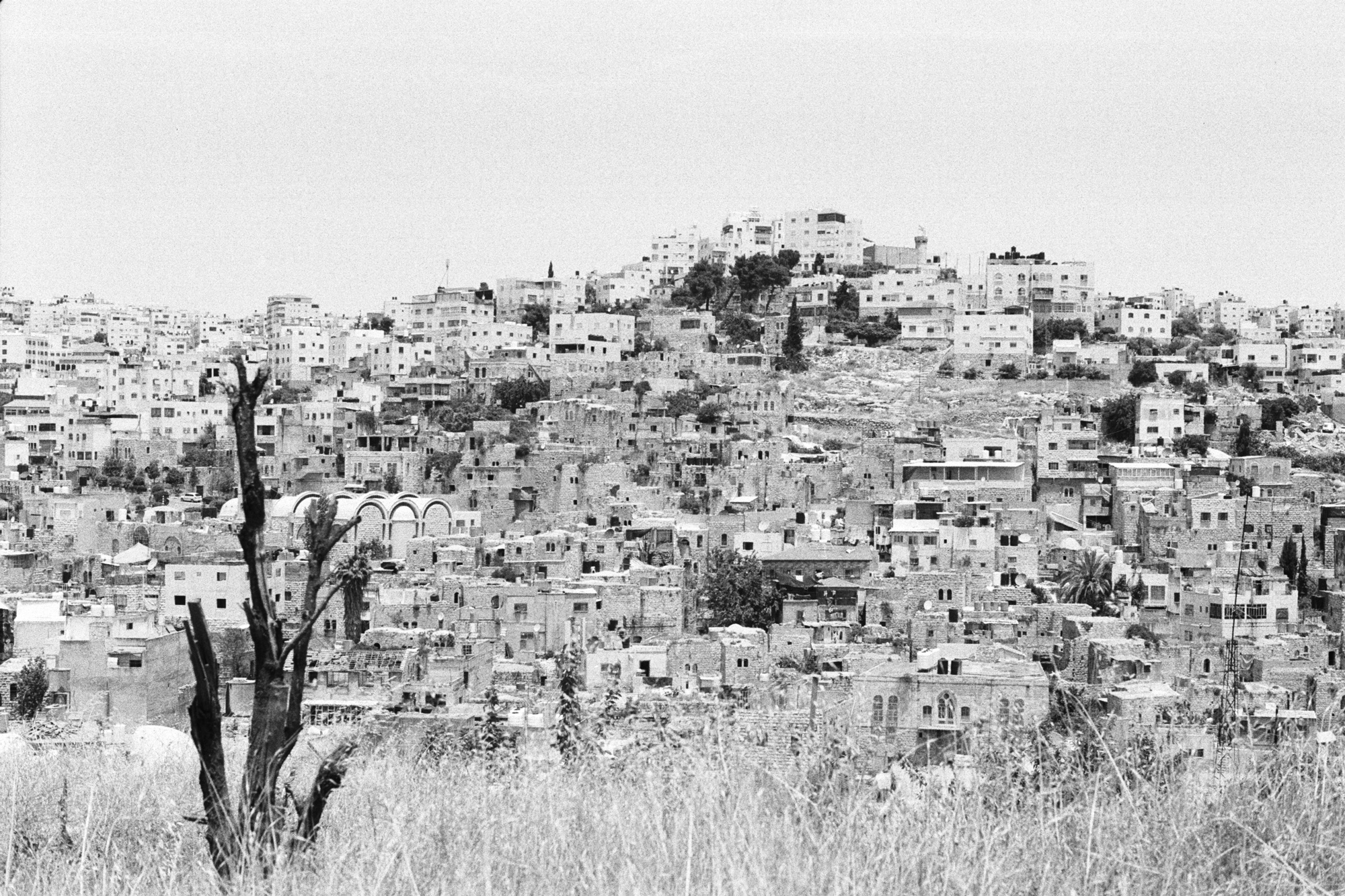

It is not my habit to add a textual apparatus to accompany the music I make. One doesn’t need guidelines to listen to a track, an album, a melody, or a song. These brief lines are not meant to guide anyone, nor to explain how to listen to it. They are simply an attempt to open a small window onto what lies behind Karakoz: where it comes from, how it has transformed, through which hands, stories, territories, roots, landscapes, and encounters it has passed before reaching your turntables. Karakoz is a tale that travels from Calabria to Palestine, from Crotone to Bethlehem, across the waves of the Mediterranean, a sea that welcomes and exchanges, kills and devours.

What does it mean to cross Palestine in the midst of a genocide? It is a question I keep returning to, one for which I have no single answer. But the one that comes back most clearly is that of responsibility. Between January and May 2024, I travelled through the land and the people who live between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, thanks to the support of Radio Atheer in Ramallah, Radio alHara and the Wonder Cabinet in Bethlehem. Faces and names have marked this journey in ways that cannot be undone.

The pages that follow collect three conversations with some of the people who made it possible: Palestinian architects, co-founders of Radio alHara, the Wonder Cabinet, and the architectural studio AAU Anastas, Yousef and Elias Anastas,, tireless hearts and engines of Bethlehem’s cultural scene; Ibrahim Owais, Palestinian musician, co-founder of Radio alHara, and artistic producer of the Wonder Cabinet; Maya Al Khaldi, Palestinian musician and producer, with whom I had the joy of recording in Ramallah, a voice at once indomitable, generous, and direct. You will also find a text written by friend and scholar Micol Meghnagi, who shared part of this journey with me. For years, her work has been rooted in the Palestinian landscape, where she conducts research and maintains a presence with committed passion. The photographs accompanying these texts are by Ilaria Doimo, my life partner and devoted human rights supporter, who joined the residency to impress this journey on film and by Sofia Lambrou, a French artist based between Athens and Paris, in residence at the Wonder Cabinet between January and June 2024. None of this work would have been possible without the thread that helped bring encounters together.

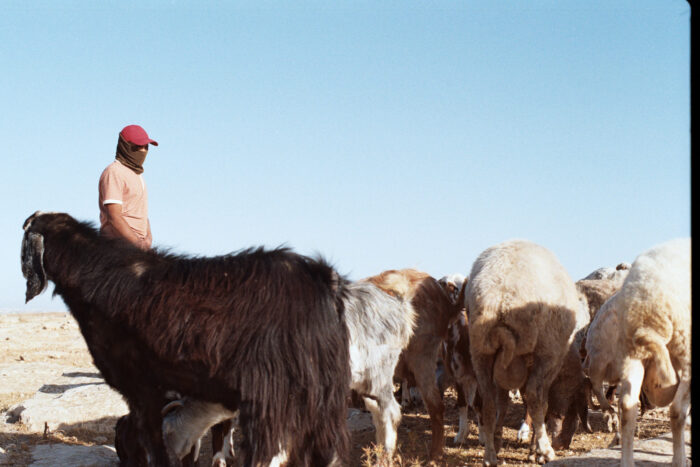

What does it mean to make music in the midst of a genocide? I asked this question to everyone. Perhaps, among the waves of Karakoz, you will find an answer, or several, or none. Karakoz is a blend of Palestinian traditional materials and instruments, suspended between past and present, rewritten inside my dreamworld. Karakoz is an archive of acoustic photographs that crystallize places and memories through field recordings gathered in the streets of Ramallah, Bethlehem, Hebron, Jerusalem, and across the land of the South Hebron Hills and the arid slopes of the Jordan Valley. Karakoz is a puzzle of voices and sounds: traditional musicians, experimenters, ancient timbres, lyrics, and conversations that weave a narrative. Karakoz is an attempt to be present, to create memory, and to render it impermeable to borders and to those who impose them.

“The Mediterranean is not a sea; it is an expanse of questions,” wrote the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish. An expanse of questions runs through Karakoz, among shadows and spirits rising from the seabed and washing ashore. Karakoz is a theatre of shadows, stories, and memories suspended between space and time, continuing to exist. And to resist.

A note on the hands and voices behind Karakoz

Maya Al Khaldi is the outstanding voice that opens Karakoz, reinterpreting a traditional funeral lament in the album’s first track, Grief. I first met her in Ramallah and at Radio Atheer studio we had the chance to record this beautiful track. Julmud, whom I had long wanted to meet and involve in a project, was the sound engineer during my residency at the studio, and in addition to his technical care he also lent his voice to Dawn on the Cremisan Valley. We recorded some great rhythms with Jihad Shouibi on riq and bandir and some traditional tunes with Karam Fares on buzuq. I also had the honor and pleasure of meeting and playing with Maestro Osama Abu Ali, a leading exponent of traditional Palestinian music. He gathers bamboo from familiar places near his village, makes his own flutes (yarghul and mijwiz), and plays nonstop throughout spring and summer, weddings, village festivals, and other festivities. Playing with him was inspiring and mind-blowing: the sessions and improvisations came naturally, almost as if we had been playing together for a long time and simply resumed something already in motion. Another essential thread of this journey is embodied by Alabaster dePlume. A mutual friend, Chiara Civello, connected us before the trip, though we actually met in person in Ramallah.

After Sounds of Places live set Alabaster DePlume, Sami El-Enany, Mai Mai Mai. Photo Ilaria Doimo.

For Sounds of Places, we played as a trio with Alabaster on sax and vocals, Samy El-Enani on piano, and me on electronics and percussion. That set was intense, in a place that felt both powerful and fragile. It isn’t the live session that ended up on the album. Instead, the record carries a different trace of that encounter that we called Echoes of the Harvest. In this track, Alabaster’s saxophone appears on its own as a third voice woven into a pre-existing dialogue: the slow pulse of a Buchla carrying an “olive-harvest chant;” a traditional work song sung during the olive harvest, where voices move in rhythm with labour and hold the memory of the place. The recording comes from the archive of the PAC (Popular Art Center) in Ramallah, a cultural centre whose village recordings, some made in the 1990s, some in 2020, exist as a living geography.

Jihad Shouibi and Karam Fares. Photo Ilaria Doimo.

Listening to that archive, with its cassettes and field recordings, immersed me in times and situations that sound alone can still transmit; some of those files entered the album and made the journey even more haunting and nostalgic, carried by a shifted temporality that envelops and surrounds us. And finally, these sound tales would not have this form without the precious collaboration of Filippo Brancadoro, in his studio in Rome. We spent intense days over the past months working together; thanks to his mastery and patience we shaped these tracks, and without his hands and ears, crafting beats, mixing, and producing, I would not have been so satisfied and proud of how Karakoz sounds.

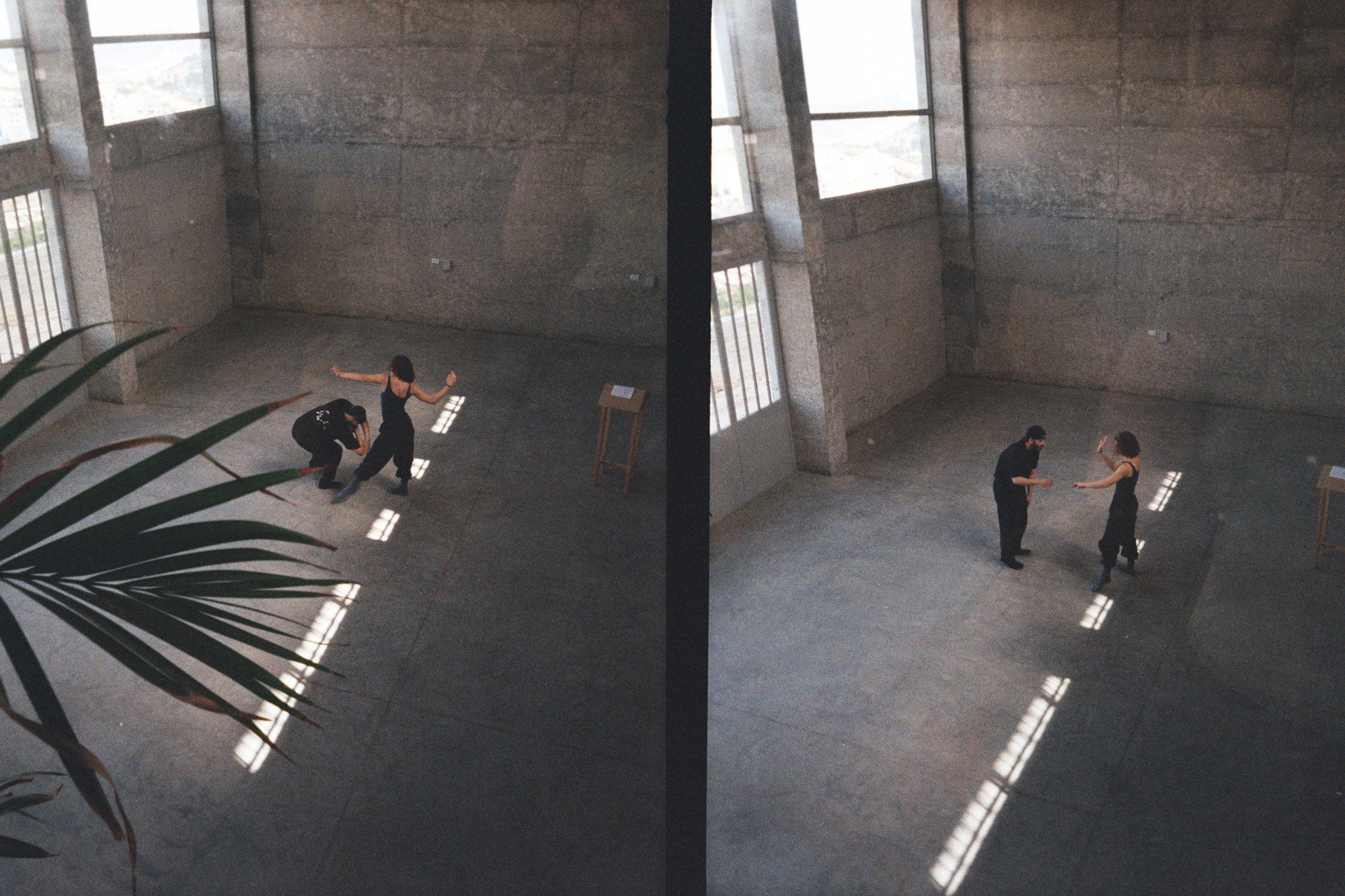

“The Right of Opacity” by Micol Meghnagi

From the Cremisan Valley, the city of Bethlehem appears torn open, split by the wall that drags it away from Jerusalem. A structure longer than 700 kilometers, completed in the early 2000s, the wall cuts through orchards, families, and entire ecosystems. It is along this wound in the land that, between 2024 and 2025, Sounds of Places emerged: an artist residence envisioned by architects Elias and Yousef Anastas and rooted in the Wonder Cabinet, their polyphonic cultural space of Bethlehem that houses Radio alHara’s global broadcasts and the architectural practice AAU Anastas. The Wonder Cabinet is a laboratory for everything that refuses categorization: sound, architecture, cooking, design, and craftsmanship. A place where forms collide, rub against one another, and generate new ones. Its raw concrete frame, porous atmosphere, and insistence on collective presence stand in open defiance of the rigid spatial regime surrounding it.

Bethlehem Separation Wall. Photo Ilaria Doimo.

The Cremisan Valley lies in Area C of the occupied West Bank, under full Israeli military and administrative control. It is one of the last green breaths of the Bethlehem area, and one of the territories that should have belonged to a future Palestinian state. Today, it is bordered by construction sites, bulldozers, expanding settler outposts, and the persistent threat that the separation wall may soon cut directly across it. Despite the court rulings that once attempted to halt its expansion, Israel has resumed construction. Barely one hundred meters remain before the wall closes around the valley, slicing through a monastery where monks and nuns have produced wine since the 1960s. Few grasp that the wall is, paradoxically, the weakest part of the occupation. What appears to be a fixed barrier is, in practice, a reconfigurable infrastructure: sections can be rerouted, dismantled, and rebuilt. In Eyal Weizman’s term, it is a slow, methodical instrument of domination, whose power lies not in height but in the continuous reorganization of life.

While Gaza is being devastated, its neighborhoods are turned to rubble and its infrastructures are annihilated, whilst the rest of the West Bank undergoes an accelerated process of colonization. Since the Oslo Peace Agreement, Israel has separated the West Bank from Gaza; then East Jerusalem from the rest of the territories; and finally, Palestinian villages from one another. The rhetoric of “security” is never merely defensive. It is a mechanism designed to justify fragmentation and erasing any continuity of land, politics, and community. Cremisan is one such fragment. But it is far from alone.

Hebron checkpoint. Photo Ilaria Doimo.

Across the West Bank, I have spent years witnessing bulldozers tear down infrastructure, level agricultural fields, destroy springs, and erase village roads. At times, violence took on faces I knew and loved. One of them was my friend Awdah Hathaleen, a Palestinian community leader from Umm al-Kheir in the South Hebron Hills, killed in July 2025 by the settler Yinon Levi, who shot him after entering the village and attempting to cut the only water pipe that serves the community. Awdah recorded the moment of his own death. An American Jewish activist beside him, engaged in what we call protective presence, [1] witnessed the shooting and tried to save him. He later testified that the settler laughed at Awdah’s body as he lay dying. Ydon Levi spent only a few days under house arrest. He was then released, and every day, even as I write, he continues to enter Awdah’s village, harassing and intimidating his grieving family. Awdah Hathaleen is only one among many whose faces flicker briefly across the news, most often without a name.

Masafer Yatta. Photo Ilaria Doimo.

And yet, in Palestine, life persists. In Cremisan, Sounds of Places turns a valley under siege into a site of sonic, spatial, and communal possibility within and beyond the occupation. For decades, Palestinian cultural production has been confined to a pre-packaged interpretive box. The world demands legibility and demands it in advance. When Palestinian artists address subjects other than violence or dispossession, I have often seen reactions of disbelief, as if they were neglecting an assigned duty. Painter and theorist Samia Halaby has offered one of the clearest critiques of this framing. In a 2017 interview with Mona Khazindar, Halaby explains that the label Palestinian artist is politically necessary today only because of ongoing structures of domination: “If I have to be identified as a member of a subset of artists, then my preference is to be known as a Palestinian artist. However, if we lived in a world where imperialism had been erased, I would say that I should be labeled only as an artist, without adjectives.”

But the right of opacity, in Édouard Glissant’s sense, is precisely what Palestinian artists are refused. They are expected to be transparent, explicable, and digestible. They must always represent something. Their work must confirm what the world already believes about Palestine. Sounds of Places rejects this mandate. Instead of producing yet another image of Palestine to be framed and consumed, it builds infrastructures where sound, thought, and form can expand without being policed by the demand for political readability. It creates spaces where art begins from Palestine but is not confined to Palestine, where identity becomes not a cage but a point of departure. This is the signature of Sounds of Places: the willingness to inhabit an imagined or real land, the ability to create a space that fiercely defends freedom. These sounds, gestures, and collaborations become powerful metaphors for the hope that one day the same freedom might be possible for Palestine itself.

[1] Protective presence refers to a form of unarmed civilian protection in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, where activists physically accompany and stay near at-risk communities during high-risk moments such as demolitions, attacks, evictions, arrests, movement restrictions and so on.

Mai Mai Mai and Ibrahim Owais

MMM: It was the fifth of October, something like that. We were planning to come in November and do something there, but the 7th of October changed everything. At the time, nobody really understood what was happening. Even the Goethe-Institut people were saying, Let’s wait a week, maybe two. By next month, things should be fine. Now we know how that turned out. It wasn’t a week or a month. It’s 2025, and the situation is still nothing like anyone imagined back then. But I still remember you telling me in December: If you still want to come, there’s a way. It wasn’t an easy decision, but I wanted to be there with you, to stay inside that moment. So we found a way, and I arrived in January 2024. Fresh, fragile, very uncertain.

OWAIS: And then we managed to bring you in January, yes. Your first stop was Ramallah?

MMM: Yeah. I spent the first ten days there. I met Julmud, recorded in the studio, and saw the city, though Ramallah was not as the Ramallah people had described. It was quiet, empty. That contrast was strong. And then I came to Bethlehem for the residency with you and we met Osama Abu Ali. Everything changed from the original plan. At the beginning we were talking about shows in Ramallah, Bethlehem, and even Amman. Maybe Beirut. A completely different residency. But you had to rethink everything on the spot, and the Wonder Cabinet was just a few months old then.

OWAIS: Exactly. It opened in late May. Right before the 7th of October I had flown to Berlin for a gig. I landed, checked my phone, and saw the news. At first, I didn’t understand what October 7 meant. Then everything escalated. I wasn’t sure I could play at the event; it was a night with Assyouti (Egyptian, Berlin-based DJ and producer) and Sara Persico (Italian, Berlin-based musician), but we decided to go ahead. After that I couldn’t return. Borders were closed. The whole West Bank was sealed off. The strange part is that we were all outside. Elias was in Europe, Yousef was in Paris, and Ilaria was in Milano. We were all stuck for months. We kept thinking: This will end soon. It’s another round. But then Gaza started appearing on the screen in real time, and it was unbearable. Ilaria was the first to go back, then two weeks later I followed her. The borders reopened, we returned to Bethlehem, and everything, absolutely everything, had to be rethought. The city was empty, the atmosphere was heavy and people were numb. We had to redesign the entire program to respond to the moment, to lift the mood, to create even the smallest space of relief, and you were insistent on coming.

Toni Cutrone with Ibrahim Owais. Photo Ilaria Doimo.

MMM: Yes, because I had the feeling that if I didn’t come then the possibility might disappear for a long time. It wasn’t postponed. It was now or maybe never. And once you told me it was possible, I came.

OWAIS: Exactly. But at that time almost no international guests were coming. Tourism had stopped entirely. The first sign of movement came only months later with Sounds of Places in May 2024. And yes, by then, you and Sofia Lambrou were basically our first long-term residents. You were the first sound artist actually producing something inside the Cabinet after the war started. That period shaped everything.

MMM: I remember the dinner before crossing the border—me, you, Ilaria. And then that crossing at 7 a.m. The Bridge… Honestly, it felt dystopian. Then straight to Ramallah.

OWAIS: And there you recorded with all the musicians you found through Julmud, right?

MMM: Yes. The first person I met was Maya Al-Khaldi. We had been talking beforehand, and she immediately said she didn’t want to improvise. So we built something around her research on grief songs, laments. It fits perfectly with what I usually explore, this ritualistic ceremonial dimension. Then I recorded a lot of percussion, because I knew the album needed that physicality, and I did field recordings around Ramallah, which was eerie as it was my first time and everything was so still, so stripped down.

OWAIS: Ramallah was unrecognisable at that time.

MMM: Exactly, and that dissonance became part of the project. But what I really want to ask you is about the way you reacted to everything. The first version of Sounds of Places was supposed to be almost a festival, shows, club nights, and collaborations with people from abroad. But after October 7, you shifted completely. You responded to the situation instead of forcing a format, and what came out, especially in May, felt like a form of resistance.

Julmud in Radio Atheer Studio. Photo Ilaria Doimo.

OWAIS: Sounds of Places had been planned since 2023. But yes, the original idea had concerts, club nights, and international guests. After the war, we had to rewrite everything. By January we decided the focus had to move from festival to place. To the valley. Cremisan

is the last green area of Bethlehem. We had already been working there with installations, research, and performances. So the new Sounds of Places became an act of listening to that land, its fragility, its history and the threat of it disappearing. We worked with artists in Beirut who were unable to travel. That forced us to invent new collaboration frameworks. We built Jad Atoui’s installation remotely, sound produced through interactions with nature. Yara Asmar’s wind-chime installation now lives at the monastery. Tarek Abboushi’s sound chair. All of them spoke to the valley and amplified its presence. Then came the performances: Faster Than Light (with Sasha Shadid, Adan Azzam, and Julmud), the pieces by Peter Kirn, by Tarek, by yourself and Alabaster DePlume, and Sami El-Enany. All of the works created are still touring. Albums, EPs, and new installations. The resonance keeps expanding.

MMM: It was intense. Working in that valley, with all of you, was a lot to take in. I think every artist is left with too much material, emotionally and sonically. It took me months to process it. My album is basically the story of what we lived there, without words. And that’s why I wanted to include this conversation, so listeners can have a wider frame, understand what was happening around the music. Leaving Bethlehem was hard. Both times, the only thought was: we need to come back soon.

OWAIS: It really was an emotional rollercoaster. And that’s why Sounds of Places must keep travelling. So the valley, the people, the sound, none of it remains isolated. It keeps moving, living, connecting.

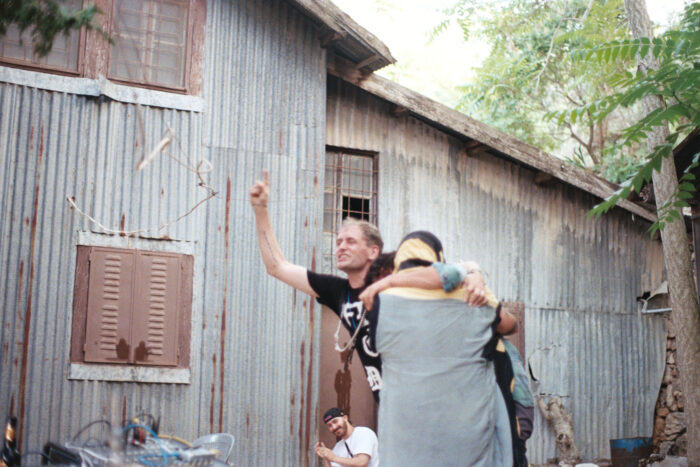

Kitchen takeover at Wonder Cabinet. Photo Sofia Lambrou.

MMM: You were the first one I met amongst all of you. From the very beginning, you kept telling me the same thing, that one of the most important things here is to build a community. Nothing is easy. It’s not easy to bring people here, not easy to move around, not easy to invite artists who in many cases cannot even enter. So before meeting the others, I already understood from you that everything around the radio and the Wonder Cabinet exists because people insist on staying connected, on being present, on holding the place together. And when I finally arrived, I could see exactly what you meant.

Owais: Exactly. Especially people from Lebanon and Syria. It’s impossible. We had an artist from Iran as well who couldn’t come.

MMM: So in a way I was very aware of my privilege, arriving with an Italian passport, even if I had to “fake” being a tourist, pretending to be on holiday. I remember talking about this with Marwa Belha, our mutual friend from Tunisia. She told me I was lucky as she could never go.

Owais: Yes, also people from Tunisia cannot come. It’s very difficult.

MMM: But it’s great that you’re taking Sounds of Places abroad and that we did it together in Rome as well.

Owais: Yes. We brought Sounds of Places to Le Guess Who? in November 2024, then to Rome at Brancaleone in March 2025 and this October we are bringing it to the Triennale in Milan. In November we will return to Le Guess Who?

MMM: There was a plan to do it in Paris before Rome, but it didn’t work out, right?

Owais: No, it didn’t. It was too fast. We were too ambitious, as always. [laughs]

MMM: So what’s next? What do you imagine for Sounds of Places and for the Wonder Cabinet? Because I’ve seen you are doing so many residencies now and not only sound. There’s video, photography, art, and even food.

Owais: Completely, and you were part of that, too. You weren’t just about sound, your main mission was cooking an amatriciana.

MMM: And making a Bloody Mary. True.

Wonder cabinet and the view. Photo Sofia Lambrou.

Owais: Each residency has been perfect for its moment. Your residency in January, Sofia Lambrou’s residency, and then Sounds of Places, each evolved naturally. All the content produced came from the situation here: the war, the atmosphere, the emotional state we were all in. Right now we have many projects running. One of the main ones is the Bar and Radio Residency, where people take over the bar and the radio, create programs, curate events, talks, music sets, and even redesign the menu. We had Xinyu from China, who transformed the kitchen into a Chinese restaurant. We had Julio César from Venezuela, who works with sound installations and created the Listening Club. This residency is ongoing; every season, we change the participants selected from an open call. We also have smaller residencies, like “One Land” with Ahmad Al-Aqra. Others will come from a project we call the “Land Project,” which works with the land around the Wonder Cabinet and the local community to create a park and public space. Then we have the new edition of Sounds of Places. This one will be different: it won’t happen in a single moment like last time. The beauty of the first edition was that all the artists were here together. This time, the year will be divided into four parts. Each group of artists will spend three months researching a place, and will present a Sounds of Places showcase at the end of their period. The focus will be on endangered or disappearing sounds across Palestine: from Haifa to Akka, from Jericho to Hebron to Nablus. Each artist will spend at least a month in one of these locations, then bring their research either back to the Cabinet, creating a sound installation here, or produce it on-site where they were staying. At the end of each quarter there will be a ten-day showcase. This is the master plan. Sounds of Places is important for the Cabinet because of what it created last year, a whole category of work, not just a festival. It’s no longer something that happens once a year. It lives the whole year. Any sound artist who comes here and develops a project can fall under Sounds of Places. Many of the works produced here will become part of future showcases. We are also working on new performances. For the Triennale in Milan, the idea is to recreate the Cremisan Valley as a sound installation: you enter the space and feel as if you are in the valley, through spatial sound made from our field recordings. Two artists from Sounds of Places, Tarek Abouchi and Samuel Anani, will intervene in the piece. Tarek is already confirmed; Samuel’s work from last year may be part of it as well. At Le Guess Who? we will present another version, this time with Alabaster and Yara Asmar, who will perform with the sounds of her installation. The concept keeps evolving.

Mai Mai Mai and Maya Al Khaldi

MMM: I think you were the first person I met when we arrived in Ramallah. We had just crossed the border from Amman; no one from the Institute was there yet, so Ilaria and I ended up walking through the city trying to reach you. Then we met and it felt immediately right. I really wanted to work together, and I am very happy we did. I remember that when I first asked if you wanted to collaborate the first thing you told me was that you’re not into improvisation, which is funny, because that’s what I usually do. You said you prefer working with texts, with lyrics you can sing, and that led you to tell me about your research, which I found beautiful and powerful. Maybe you can talk a bit about that, where your work was at that moment, and what it meant to bring it into our collaboration.

Maya: When you contacted me it was a very specific moment. It was still the beginning of the genocide, and we were only starting to understand what was happening and what our place inside it was. I couldn’t make music then. I didn’t want to. I was already researching grief songs, and the question behind the research was exactly that: what am I supposed to do, as a singer, with all this grief? What does it mean to have a voice while a genocide is happening to your people? So when you arrived, the only thing that felt honest was to sing a grief song. To meet you from where I was. You were coming into Palestine in a moment of overwhelming sadness; I needed to share that with you. For me, it was part of understanding what music could still do.

MMM: It really was an incredibly hard moment. When I talked with Ibrahim Owais and the crew in Bethlehem, we were all conflicted: we had planned everything in September, and the idea was to come, play, move around, and do shows. Then October changed everything. Nobody knew whether it even made sense to do anything. But at the same time there was a need, a need to do something through art because that’s what we have. I didn’t want to push anyone or impose anything. I wanted it to be something that came from you all, if at all. You were one of the first to show that there was a need. Even though Julmud hadn’t touched an instrument since October, when we worked together in the studio, he found something again. So yes, the surroundings were terrible, but inside the studio, we had some really meaningful moments. I hope it was good for you too.

Maya: It was, but also very conflicting. Working at that moment was challenging. Working with someone who is not Palestinian adds another layer, not because you don’t feel things, I’m sure that you feel things. I mean, obviously, you were there, but because, of course, it is different. Also, you live in the West. Even if Southern Italy feels culturally closer, you are still in a different position from ours. So it wasn’t easy but it was intellectually and emotionally interesting. But I think we managed. The work itself was smooth; we didn’t approach it like outsiders studying something. It was intuitive. But it’s definitely something that’s important to think about. When in this very specific moment, someone like me meets someone like you, right?

MMM: Absolutely. And your research was already going in that direction before October. I knew you were working on Palestinian folk traditions, and you told me these grief songs had almost disappeared. That struck me and it felt like reviving something that risked vanishing completely.

Maya: Yes. I had already begun the research, but after the genocide, it became even more urgent. Grief songs, or wailing songs, used to be sung around funerals, or when someone left for somewhere far. They’re performed by women, and they’re part of a ritual that involves movement, crying, and screaming. Many traditions were broken after the Nakba in 1948; people had to leave everything overnight and communities lost continuity. But another important factor is religion. In the 1980s, Wahhabi interpretations coming from Saudi Arabia declared these songs haram and forbidden because in many of them, women address God with anger: Why did you take this person? Why did you do this to me? So many women stopped. The songs became rare. Most of what I found are texts, women speaking the words but refusing to sing them. I found only a few actual recordings, mostly from Christian villages where the practice survived slightly longer. So part of my work is to bring them back: to find lyrics, compose melodies, and imagine what these songs could be today.

MMM: I remember when you told me this, I immediately thought of something similar in Southern Italy. Not identical in form, but similar in intention. We had the prefiche: women who sang, cried, screamed around the dead body. They were meant to guide the soul of the deceased, to accompany them. It’s an ancient Mediterranean tradition, with traces of the Greek language in some regions. And it survived until the ’90s or early 2000s. It’s fading for different reasons, partly because the Church disapproved, partly because the South was pressured to erase what made it “different.” In one of my albums, I used a recording from the ’60s of a woman singing one of those laments. So yes, I felt a resonance with what you were doing in Palestine.

Maya: You showed me that recording. Yes, I think these traditions disappear everywhere for similar reasons. They are intense, emotional, and they challenge religious authority. But your connection to southern Italian folklore makes sense.

MMM: Yes, I grew up surrounded by it even if I didn’t really live it. My parents were philosophers, intellectuals; they didn’t practice these traditions. But at a certain point, I felt the need to go back because they were disappearing. In Italy, when the country unified, the South was treated as backward. There was a rush to become “like the North,” and everything that didn’t fit that model was erased or hidden. Only in the last twenty years people have started reclaiming their own culture again. And I realised that what I feel culturally isn’t “European”—whatever Europe and European mean—it’s more connected with the idea of the Mediterranean. That’s why I felt close to what you and others are doing. So working with you was also a way to meet your culture through sound, directly and intimately. Music bypasses so many barriers. It goes straight within the body. And yes, I reached out first because I loved your album, and because I read you were researching Palestinian folk heritage. I felt there was a kind of shared sensibility, even if our histories are radically different.

Maya: And I’m glad we worked together.

Mai Mai Mai, Elias and Yousef Anastas

MMM: I think the very first person from your group that I actually met was Ibrahim. I met him in Italy and then again in Berlin, and he had already told me a lot about you. But you and I met properly only in January, when I came to Bethlehem. I was trying to remember whether we had ever crossed paths earlier in Ortigia, maybe just for a second, but I don’t think so.

Elias Anastas: No, no, we hadn’t. The first time was in Bethlehem, in January 2024.

MMM: Right. By then, I already had quite a lot of information about you and about what you do, especially about this beautiful project, the Wonder Cabinet.

Elias Anastas: Yes. The first thing that really took shape publicly was the radio as a collective project. But the Wonder Cabinet started around the same time we began thinking about the radio. The radio began in March 2020, and that COVID moment really pushed us to think about how we wanted to continue our practice: how to work internally, how to make things public, how to connect architecture and art, and how to expand the work to a wider community. As you know, the core of our practice is architecture, but around it there are all these things that hover: sound, production, design, and the network with makers. So we thought maybe we could create a space where all these possibilities could live together in one building, and where new things could emerge across disciplines. And we were lucky, because in 2020, we met someone who really believed in the project. She had worked at the Swiss Foundation. She was a Palestinian woman who, unfortunately, passed away, but she truly supported us, both mentally and financially. That’s what allowed us to start the Wonder Cabinet.

MMM: Yeah, I have to say that when I arrived at the Wonder Cabinet… First of all, it’s really beautiful. It really fits the landscape, and the mood of the hills around it. The view of Bethlehem and the settlement from the window is intense. It’s like: okay, this is where we are. It feels like you found the perfect balance between the territory and the people who are working there. When you see the place, you immediately understand the community behind it. And it was really lovely to be there with you, because I really felt, maybe even more than a community, like a family. When I came in January, the international artists were just me, Ilaria, and Sofia. We were the only three residents. Later, already in May, sometimes we were 8, 10, 12. But in January, it really felt like a small family.

Toni Cutrone with Manaal Oomerbhoy. Photo Ilaria Doimo.

Elias Anastas: Actually, yes. January was a very special moment, because the Wonder Cabinet opened only in late May or June 2023. Between May and October 7th, the space was just starting, and we were still figuring out how it should work. It was a very intense period, the program was beginning, then we travelled and got stuck outside Palestine for weeks. When we came back, we decided we just needed to open the building, even though nothing was happening inside, and the people who came started proposing things: watching films, cooking, and using the kitchen. That’s what shaped the program. Up until today, we’ve kept this way of operating. At the beginning, we thought the Wonder Cabinet would be a production space, focused on culture and making. But after everything that happened in these two years, “production” also became responding to neighborhood needs, older people, young people, and being a space for sports, yoga, and so on. So the space, both architecturally and conceptually, keeps transforming and adapting to different conditions.

Recording Osama Abu Ali in the Radio alHara Studio. Photo Sofia Lambrou.

MMM: Yeah. I really felt this kind of total immersion in the place, the community, the family. Also, because we were doing music, and you showed me the Local Industries space. Then we had the workshop; I did the workshop with the kids, too. Then we all did the kitchen takeover together, Ilaria and I prepared some Italian cooking at the bar. They were really amazing moments. When I arrived in Bethlehem, I had just spent ten days in Ramallah, where I met Julmud and Maya Al Khaldi, and the atmosphere there was totally different. Ramallah has such a different mood from Bethlehem, and also compared to your environment. So, when I arrived in Bethlehem, the first thing we planned was the meeting with Osama Abu Ali. I remember Yusef showing me videos of him playing. I don’t know if they were from a festival you invited him to, or the Boiler Room thing, or maybe a wedding. But I remember watching the videos and thinking, okay, this guy is amazing. It was great that you had the idea to introduce me to him and bring him to the Wonder Cabinet for the recordings. That was an amazing moment. How did you get the idea?

Yousef Anastas: I mean… this guy, Osama Abu Ali, is really, well, now that we look back at what happened with him at the Wonder Cabinet, and what he did with you and with other artists, he basically represents a part of what the Wonder Cabinet is. He’s a superstar, but on a local level, you know? A local hero. He’s a hero, but without any ambition to go beyond that. No goal of becoming “more.” I think that’s actually very respectable, and it creates anchors in the society. He became one of these anchors. We discovered him because there are so many YouTube accounts of local music labels that are really popular. Some of them are called Laser Cassette, Master Cassette, things like that. They have YouTube channels full of recordings, different qualities, different settings in the landscape, sometimes in a studio. Weird stuff, sometimes better stuff. Weddings, non-weddings. It’s weird. But Osama Abu Ali was in one of those videos, playing the yarghoul, the instrument he also fabricates, somewhere in the landscape, maybe near a small water source, a river, or something. And he was playing the yarghoul in this very romantic place.

He’s interesting because, apart from being this local hero and anchor in society, he also represents a solid economic model for musicians. At the end of the day, he is a musician. Most of his work is indeed weddings, mainly, but still, he’s really a musician. So, he also teaches music in schools, he fabricates the instrument, he plays it, he makes models, and so on. From the weddings, he makes it whole… like, he’s fully booked at least seven to eight months a year, which is completely crazy. It really represents an economic model that is very interesting to understand and to learn from.

Osama Abu Ali and Mai Mai Mai. Photo Sofia Lambrou.

Elias Anastas: What’s really special is that many extraordinary musicians in Palestine can’t sustain themselves through their practice. Osama is exceptional not only because he’s a remarkable musician, but also because he’s so open-minded, able to collaborate with you, or with someone like Dirar Kalash, and to stretch his knowledge into other areas. At the same time, he stays deeply rooted in the musical traditions of weddings. I remember when Yusuf first discovered him, probably through some YouTube video of a wedding, one of those random uploads from local labels.

MMM: Yes, we saw one of those videos online, Osama playing in a wedding somewhere outdoors.

Elias Anastas: Exactly, and then, after the Boiler Room project, we had an invitation to curate a music event in France. Yusef immediately thought: We need to take Osama with us. So he called him, this was in May. Yusuf was very excited, telling him about the opportunity. Osama just said: In May? I don’t want to go to France. I have so many weddings to play. His reaction was actually beautiful. It made us understand something very simple and very true: he didn’t need to perform abroad to validate his work. He was already doing exactly what mattered in his own community and sustaining himself through it.

MMM: I was a bit nervous before meeting him, because in the videos the weddings looked huge, very different from what we’re used to in Italy. Even in Southern Italy, weddings can be big, but those videos showed hundreds of people, sometimes maybe even more. But Osama turned out to be incredibly generous. I often work with traditional musicians, and sometimes, even with Calabrian musicians from where I’m from, there’s a kind of barrier when you bring in a different musical language. But with him, it wasn’t like that at all. As soon as we started recording, when I added my kick and synthesizers, he began improvising naturally on top of them. It felt like we’d been playing together for years. It was really impressive.

Elias Anastas: What is also really interesting about Osama is that he is not only a musician. He is a producer, a maker. He builds the instrument he plays, and this instrument is now practiced by a very small number of musicians in Palestine, probably only a few still know how to physically make it. This is something we care about a lot: the transmission of knowledge, to transmit it in a way that is not always tied to a linear idea of history, but also open to contamination across time. So, for example, when Osama starts speaking with other musicians or other fields of production, you are able to witness how what he does with this instrument can be transformed by others in completely different contexts. This also happened with other artists. In the period between the opening of the Wonder Cabinet and the war, Asifeh was visiting. You know him, he is an amazing producer from Palestine, based in Vienna. We immediately thought of doing something together at the Wonder Cabinet. But we always try not to treat the space simply as a venue. When we invite an artist, we try to produce something specific to what the Wonder Cabinet is. Like your collaboration with Osama Abu Ali. With Asifeh, we developed the idea of building an instrument with our team of blacksmiths. The instrument was made entirely of steel and was designed to amplify his voice and his rapping through its structure. It was beautiful to see our team, who usually work in architecture and design, suddenly speaking with someone completely outside their usual world. They began discussing resonance, amplification, materials, and insulation. All of this created an object authored collectively by the Wonder Cabinet, the artist, and the artisans.

MMM: Yeah, exactly. If we jump a few months forward: when I came back in May for Sounds of Places, there were more people around, and the first thing you brought me to was the Local Industries space, where you were building the tubular bell installation. I remember this continuous exchange between the person designing it, the musicians, and the guy manually building it. We were all trying to understand how to make it sound better, what adjustments it needed. It really felt like a perfect example of community: people from different backgrounds, jobs, and cultures working together to build something. That installation was made for Sounds of Places, and then you placed it in the Cremisan Valley. Sounds of Places is such an amazing project. It has a deep core, it is really a project for the land, and for this edition it was the Cremisan Valley. But what struck me was the way you created this project, this idea, and this connection with all the musicians, artists, and residents. What can you tell me about that first edition of Sounds of Places, and how you got to that point?

Yousef Anastas: I think Sounds of Places actually started from Cremisan. We had already been working in the Cremisan Valley for a couple of years, in different ways: architecturally, but also with the community there, the monastery, and all the politics around the valley. And Sounds of Places came out of that context, even if, to be honest, we only understand the real reasons afterwards. When things happen we never see the full picture, it becomes clear only later. For me, Sounds of Places was above all about the right to fiction. This is why your work, and the work of so many residents, fit the project so naturally. The right to fiction, because this first edition was deeply linked to a physical space—the Cremisan Valley, which is politically charged, full of history and conflicts, with more changes coming. The idea was to work with the sound of that place, and strictly with sound. And sound can travel,it can relate to other places, entering the imagination of people who have never been there. You can build a sense of belonging through sound that is sometimes stronger than through images. If you see an image of a place, you’re stuck with that image. But with sound, you can connect it to other landscapes. You can imagine. Sound opens a space for fiction. This becomes important in Palestine, where we are constantly pushed into documentation. Most films are documentaries. Everything is documented. At some point, it becomes almost unproductive. So Sounds of Places was also a way to claim another space: not just the documentary, but fiction as a form of knowledge and relation. I think your work resonates with that, because your relation to ceremonies and rituals is very real, but it also triggers something fictional, something imagined, revived, reconstructed.

Mai Mai Mai live in the Cremisan Valley.

MMM: Yes, absolutely. What I usually do is deeply connected to Southern Italy, to an older Calabria that I sometimes feel doesn’t exist anymore. We often preserve it in a sort of museum form: folklore festivals, holidays, things that feel almost pretend. If you try to experience what the “real” Calabrian or Southern Italian tradition might be, sometimes there’s nothing left. So through sound, which I think has the power you’re describing, I try to reach people emotionally and bring them into that place. When people listen to Mai Mai Mai, I hope they travel. That they are, for a moment, in Southern Italy, inside a ritual, a ceremony, something that marks a change of season, something Christian or pagan. My sound is a way of taking people somewhere. So the Sounds of Places project fits perfectly with what I do. Working with the sound of the Cremisan Valley, with all its layers, made complete sense. I arrived as an outsider, someone from Italy, but as soon as we went there together, I saw everything: the monastery, the olive trees, the monks making wine, and also the walls being built to cut the valley and expropriate it. For me, it felt like a meaningful action, almost a form of resistance. Using our work, our installations, our recordings, to hold memories in the valley: the photographs, the video, the sound, the concert, and performances. It was a way of keeping the valley alive and at the same time opening it to others. People in Italy were following what we did. Many of my friends wrote to me saying they felt like they too were there in the Cremisan Valley. They understood a bit of what it means to be there, why it matters. Through what we did we brought a lot of people to Cremisan, even though they were far away.

Elias Anastas: What Yousef was saying is very true; sometimes you begin a project with one idea, and yet once you begin working on it you realise other stronger ideas emerge along the way. Cremisan was like that for us. We grew up near the valley and as kids we would go there with our family, to the park, to the hills, to spend time in nature. Then in 2004, when Israel started building the wall in Bethlehem, the annexation plan threatened the Cremisan Valley as well. The Holy See intervened, asking Israel to shift the path of the wall so that the church, the convent and the winery would remain on the West Bank side. There is also a school there which is very important for the city as many children go there for nursery and primary classes. Sorry, there’s a wedding passing by.

MMM: Wow, is that Osama playing?

[laughs]

Elias Anastas: It’s possible. Weddings here can pass anywhere.

[laughs]

What happened next in the valley was incredibly powerful. One of the monks decided that every Friday, he would hold the mass not inside the church but down in the valley itself. People who normally prayed in the church began joining him there, standing in the landscape as a way of resisting its elimination. Every Friday at 4 p.m., the gathering grew: first the usual parishioners, then others who wanted to be present in the valley, to mark it with their bodies. It even included people who were not Christian. For us, this went beyond opposing annexation. It was a moment of understanding how deeply the relationship to nature is rooted in Palestine. Everything here is linked to nature: the topography, the hills, the mountains, the sea, the food, and ultimately the land itself, which became the central symbol of Palestine. So the gatherings in the valley became a way to think about nature, not only about occupation. In 2018, we were commissioned for a project at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. We decided to anchor that project in Cremisan. We looked at those gatherings and asked how they could become architectural. How the architecture of a specific site in the valley could become a cultural claim over nature, something that stays there permanently. The project was conceived in relation to the valley, shown first at the museum, and then we brought it back to Palestine and installed it permanently in Cremisan. From there, we began activating the structure with performances, inviting artists like Julmud. Since 2018, this link with the valley has continued through small gatherings and events. Sounds of Places is essentially a continuation of that history.

MMM: Amazing, and the installation is still there. When I come back in December, we can go see it again.

Elias Anastas: Yes, absolutely. When you come in December, we’ll do something in the valley. Sounds of Places is meant to be a yearly project. We’re trying to commit to that rhythm, even though the last years have made it difficult to imagine how to navigate anything. But sound is a powerful medium. What remains from Sounds of Places is not only the installations and performances, but the fact that so many people came to the valley and spent time there, artists like you, and people who came specifically to listen. Time in the valley is something rare now. Yesterday, someone told me he went for a short hike, barely five minutes into the

valley, and the army appeared on the road with loudspeakers ordering him to leave. Using this part of the city is becoming impossible.

MMM: That’s terrible… I heard from Ibrahim that you’re already thinking about the next edition, something more spread across Palestine, involving other villages, maybe throughout the whole year. So, from Cremisan, you expand to other places, inviting artists to record and collaborate in different sites. I think that continuity is amazing. It comes from the land and from sound. What we did in Cremisan can happen in other places too.

Elias Anastas: We haven’t completely fixed what the next edition will be, but the idea comes from what has happened in the last two years: a huge process of elimination, fragmentation, and dismantling of everything Palestinians have been fighting for over decades. So doing Sounds of Places on the scale of historic Palestine matters. Many Palestinians live inside Israel, in Haifa, Nazareth, and Jaffa, and these places are important too. Activations through sound in specific endangered sites become markers of space, markers of territory. So thinking of historic Palestine for the next edition is a way to say: Palestine is here, and here, and here. It expands the map through sound. Hopefully the year 2026 will be part of it, and hopefully in better conditions than now.

Yousef Anastas: The new edition is not fully defined, but it will probably move toward the idea of places that emit and places that receive sound, simple as that. Connecting different places that are not usually connected to build another story, an alternative narrative. This can go beyond Palestine. There was the Sounds of Places you organised in Rome; we’re thinking about a residency in the mountains in Switzerland; and there will be an exhibition in Paris based on an experimental residency, a Sounds of Places laboratory exploring the materialisation of sound, how recordings can be transformed, and how field recordings become something else. All of this is becoming Sounds of Places. Eventually it might not be a once-a-year residency but a continuous process.

MMM: For me sound is fundamentally a form of connection, like water, fluid, and moving. It links people, landscapes, and geographies. It creates a kind of unity. A project that moves through time and space like this is incredibly powerful. I’m really honoured to have been there at the beginning. Can’t wait to see what’s next.