Displacing Displacement

Filmmaking against neocolonialism: an interview with Karrabing Film Collective

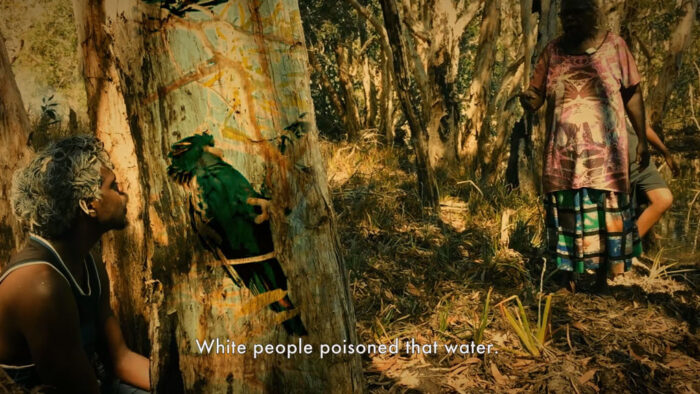

The Karrabing Film Collective was founded by members of an Australian indigenous family, whose lands stretch across the coastal region south-west of Darwin, Australia. The Collective emerged from the violence of contemporary settler colonialism, following the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act, passed in 2007, which enhanced government and police control over the indigenous people in the Northern Territory in Australia. The government intervention caused riots and upheavals, as well as the displacement of entire communities. As a response to this situation, Karrabing Film Collective began making short films as a method of self-organization and social analysis, prompted by the radical experience of becoming refugees in their own country. The Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland by Karrabing Film Collective features in the programme of DEMO Moving Image Festival.

The following interview is a transcription of part of the conversation held among members of the collective, between London, Darwin, and Berlin.

In 1963, the Yolngu people sent the Prime Minister of Australia a bark petition after the government seized 300km of their land. Australia still claimed sovereignty over indigenous lands based on the concept of terra nullius. In 1966 the Gurrindji people walked off the Wave Hill cattle station, protesting work and living conditions, land rights protests once again erupted throughout Australia. In 1971, Justuce Richard Blackburn stated that native title forms no part of state law. In 1972, four indigenous men, Michael Anderson, Billy Craigie, Tony Coorey and Bertie William pitched the Aboriginal Tent Embassy on the lawn of the Parliament in Canberra’s protest. In 1976, the federal government legislated land rights in the Northern Territory. The Act divided Aboriginal lands based on a conservative anthropological model of separate clan groups and bounded territories.

REX EDMUNDS: We also call them totems. Like fish, turtle, that’s our… That family. Family group for turtle. Family group for fish… barramundi.

LINDA YARROWIN: Durlg and Therrawin are the same animal (Sea Monster), Murrtomurrto (Long Yam), Mudi (Barramundi), Inggaraingy (Sea Turtle). Each have a place. And we know each place. And each place is a dreaming place.

ELIZABETH POVINELLI: How were they connected?

REX EDMUNDS: So from that story (The Jealous One) where it includes the Terrawin, Moiyin, and Crab, and Eagles, we have the places where those animals acted. So the story stretched from there and comes back and stretched inland and then comes out to the sea again. And we have that story line there. And that’s how our people got together and got related. And those how we are the tribe.

LINDA YARROWIN: And starting from the Belyuen waterhole they’re all connected. And that story line is still there. It still continues. We are still teaching our kids. And when you there with a boat, they are still there. And see its truth. And when you go, you get the feeling that our ancestorS are still there.

ELIZABETH POVINELLI: So everyone has their own countries and the countries are also connected?

LINDA YARROWIN: Yeah, everyone has their own and everyone is connected.

REX EDMUNDS: White people wants make us weak by saying that two or that three are the traditional owners (TO), so the other indigenous people in the area will argue with traditional owners. And white people say: let them fight each other.

LINDA YARROWIN: My mom and my dad taught us by telling us this story. The Oval Ground used to be a big ceremonial place. People made huge campfires, bring their food and tea, and they would help themselves to it. They didn’t have disco. They had all night corroborees. When it comes to ceremony time, everyone participated and doing it in a happy way, you know.

REX EDMUNDS: Everything is mucked up. White people introduced the idea and forced people to say, this land is just for that people and certain people get… and you have traditional owners for that little area and traditional owners for all kind of areas.

ELIZABETH POVINELLI: Does the Land Rights law recognise any connections?

REX EDMUNDS: No, there’s no recognitions of connections in the Land Rights Act. So everything is just fucked up.

ELIZABETH POVINELLI: Separate, separate?

REX EDMUNDS: Separate, separate, yeah. Because the government probably said: “this land here will be where we dig the mine, are you the traditional owners?” Yep, yep, that land there”. And that’s how the argument starts. Then that little part of the family gets that little money for mining there, or running tourists. And there’s another mine over there, another mine over here. And that’s why Indigenous people have been fighting. I think this was part of the cause of the riot. A similar thing happened where we had the riot.

ELIZABETH POVINELLI: And it’s happened other places?

LINDA YARROWIN: It’s happening everywhere.

REX EDMUNDS: Some other communities down in the desert area, Everywhere now. Everyone is a traditional owner of a little bit of land. Traditional owner of that little bit of land, of that other little bit of land. Then we get big arguments, spear fights, everyone killing each other, because of that. You know, it should be like where our Dreaming were – what we were saying about the stories being connected. That’s how we should be living.

ELIZABETH POVINELLI: Was it better before Land Rights?

REX EDMUNDS: I think it was even worse. They used to put a King’s plate on old man’s chests and said: “You do something wrong, we’ll shoot you and give the King’s plate to another man.

ELIZABETH POVINELLI: How is it related to the Traditional Owner?

REX EDMUNDS: You’re the traditional owner and if you do something wrong, it’s likely now, all the people will target you.

In 2007 the Northen Territory Emergence Response act was introduced by the Australian Government. This was largely in response to a report that came out of the Northern Territory into the sexual abuse of young Aboriginal children on remote communities. However, the intervention was launched on a very cynical big lie. A vicious one that smeared all Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory. The legislation that delivered this massive take over doesn’t actually mention children, but the propaganda machine, from the beginning was relentless. There was a blanket ban on alcohol and pornography. They sought to control the land of Aboriginal people by imposing five years leases, as well as preventing the Northern Territory from recognising or considering customary law. And eventually the government decided to send in the troops. These measures plainly contravened the Racial Discrimination Act, so for this Act to get passed, the Racial Discrimination Act had to get repealed.

ANGELINA LEWIS: They listen to white people, but black people… What I’ve thought was that Indigenous police were there for black people. But they’re there for themselves and who they work for. What they stand for? They don’t even stand for black people.

ELIZABETH POVINELLI: How do people treat you guys in Darwin?

GAVIN BIANAMU: Ah, shit… they always swear at us.

ELIZABETH POVINELLI: White people?

GAVIN BIANAMU: Yeah, when you’re walking on the sidewalk. Especially the police can be fucking shitty.

DAPHNE YARROWIN: When is it going to stop? Sometimes, they don’t give a fuck. You know what sister Beth? Truly, our kids are growing up in this thing is going to go generation after generation. This violence is never gonna stop. I’ve seen it since 2007. What happened? No peace. No stopping. It’s an ongoing process to be honest. And I’m sick of it.

In 2009, while still homeless, the families displaced by the riot began the Karrabing film Collective. “Karrabing” means low tide, but is also a concept and a hope for a form of relating to each other and their lands: separate-separate and connected.

LINDA YARROWIN: White people, perragut people are making decision for black people. Indigenous people, black people, should make our own decision and our own rights about our land.

GAVIN BIANAMU: You know what I like about Karrabing? It gets all our family, countrymen together, closer. And, like we all look after each other.

SHEREE BIANAMU: What I like about Karrabing is we are one big happy family.

REX EDMUNDS: Karrabing has all the tribes in it. Then we make it one big family tribe.

ETHAN JORROCK: What I like about Karrabing is getting together with my family and making these movies having fun with the crew.

REX EDMUNDS: When we come to a Dreaming site and we say: “Don’t go there, that’s the dreaming site there.” Then we tell them: “That’s your Dreaming”, if a little kid is there then, “Ah, yeah”, and so they learn.

SHEREE BIANAMU: When we were making the first film “When the Dogs Talk”, as we were going along we were learning our culture and stories from our ancestors.

REX EDMUNDS: Another thing, when we take young people to country, they feel better. They feel: “Hey, this is my country!”

GAVIN BIANAMU: Yeah, you just feel something good, you know. You don’t feel that stress inside. You’ll just be ok. You don’t have to worry about anything. It’s just like your home, you know.